11 T’Nalak: The Land of the Dreamweavers

The History of T’NALAK

Amanda David

Shiela Everett

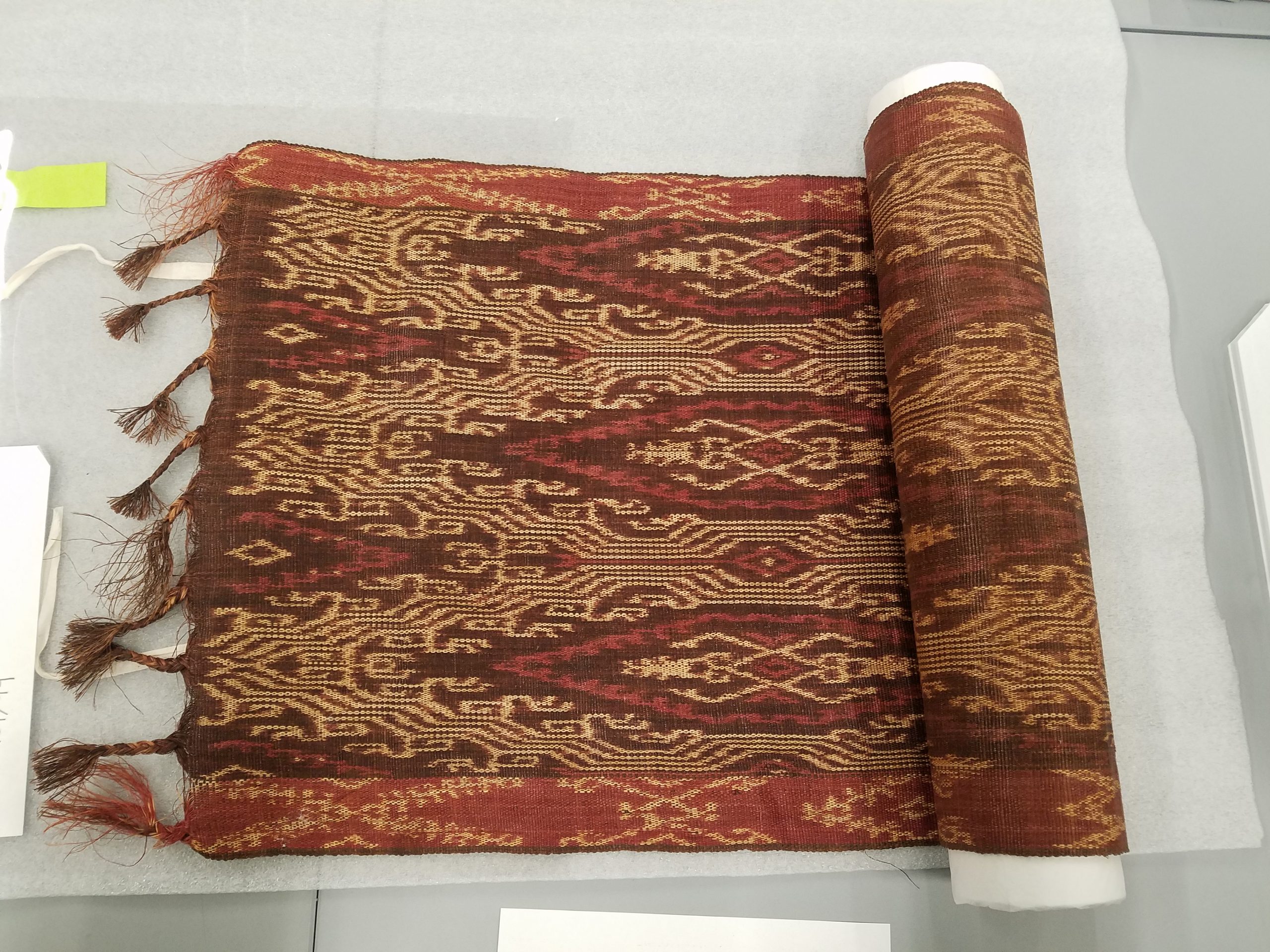

T’nalak is a traditional hand-woven cloth indigenous to the T’boli people from the Cotabato region. It is woven in order to celebrate and pay tribute to major life events such as birth, life, marriage, or death within the community. The cloth is woven from abaca fibers and is naturally dyed from bark, roots, and certain plants. The fabric undergoes a unique tie-dye process where it is tied in specific knots measured by finger or knuckle length, and dipped in dyes in order to create ornate patterns that indicate precision in craftsmanship. This is denoted by a distinctive tri-color scheme; the background is painted black while the pattern is white, which is then tinted predominantly with shades of red. However, it is not unusual to see creative variations in such a traditional pattern.

In addition to marking major life events, the cloth also conveys class and individual status, often signifying the warriors within a community. T’nalak weaving was a practice observed by women who were referred to as “dream weavers,” as it is believed that the designs and patterns were sourced from images in their dreams, as handed by the spirit of the abaca, Fu Dalu. The T’nalak woven by the dream weavers were coveted and inevitably valuable, as the women were famed embroiders and brass casters. The details required to create the fabric were taught and passed down through maternal relatives. T’nalak also was bartered in order to secure food and supplies for a family.

Our T’nalak was gifted by Nancy Davidson Short, a former Northwest editor for Sunset Magazine. It is assumed that this T’nalak was procured in the mid 1900’s. However, not much evidence is provided by the Burke Museum to establish the precise date when it was acquired, created, or how Short obtained the item. In her obituary, it was noted that her position at Sunset Magazine allowed her to travel to many places across the globe, including China and presumably Southeast Asia where this T’nalak may have crossed her path.

The T’nalak reflects core themes that can be used to understand Filipino American studies, including bayanihan and damay, which are examples of strong community partnership as participant or recipient. The whole process of T’nalak weaving, from dyeing to weaving, is descended from generation to generation of maternal relatives that necessitated a community of woven fabrics and traditional plant based-dying in order to sustain the tradition of T’nalak weaving. By creating specific coloration and subsets of T’nalak, it also provides signs of Filipino cultural identity, rank, and status.

Outside of Southern Philippines, T’nalak and other traditional Filipino fabric and garments production have been, by and large, ignored by American audiences which, in some way, extends to the institutional invisibility experienced by Filipinos and their cultural practices. Additionally, T’nalak weaving often became a substitute for income, as bartering with it increased over the years. Local and overseas work made those who stayed at home rely on cultural ingenuity in order to sustain their family. We saw examples of bartering in Carlos Bulosan’s America is in the Heart, in which he writes about the time he and his impoverished mother obtained a beautiful vase that she traded for in the market, in light of a shortage of physical currency.

The T’nalak’s cultural symbolism and connection to indigenous practice are highly relatable to the members of this group in the ways our family traditions are similarly connected to our cultural identities and heritage. It symbolizes our links to our ancestors. Because the T’nalak is traditionally woven by women of the community who apprentice their daughters to maintain such a tradition, we see this practice as something that empowers women in the community. The impact of female empowerment, doubled with the cultural significance of T’nalak, is of paramount importance to us not only because it is passed down from generation to generation, and from mother to daughter, but also because it has survived colonial rule. Though T’nalak and other forms of fabric weaving are specific to the T’boli, their cultural significance translates to how other societies and groups value their own rituals and strengthen ties to their heritage which, in turn, provide opportunities for later generations to seek a deeper understanding of themselves and their cultures.

The Artifact project has been valuable to our group. Aside from allowing us to have a deeper understanding of Filipino culture, it has also made us comprehend better the institutional invisibilities experienced by Filipinos. Additionally, we also obtained an appreciation of the work of ethnography, museum collection and management, and the scholarship produced within Asian American studies.

Acknowledgments

Kathy Dougherty Rose Mathison Prof. Holly Barker Lauren Ray Harry Murphy Maryam Fakouri

References

Lauprecht, Janvieve. “The Cultural Fabric of the Southern Philippines: Rare Textiles Make U.S. Debut in Los Angeles.” Asianweek, 1998, p. 21. Lush, Emily. “Making of: T'nalak Weaving, Philippines.” The Textile Atlas, The Textile Atlas, 9 Dec. 2017, www.thetextileatlas.com/craft-stories/tnalak-weaving-philippines. Sorilla, Franz. “Weaving the Threads of Filipino Heritage.” Philippine Tatler, 10 May 2017, ph.asiatatler.com/life/weaving-the-threads-of-filipino-heritage. “T'nalak Festival: A Colorful Celebration.” International Care Ministries, 20 Sept. 2018, www.caremin.com/2018/09/tnalak-festival-a-colorful-celebration.