12 The Vinta

The Model Vinta

Marc Joshua Antonio

Within the Burke Museum is a model outrigger artifact. This artifact takes after the appearance of a vinta, a boat whose culture of origins is that of the Philippines. Parts of the model boat have carvings that take the form of wave motifs. These carvings match the vintas mentioned by Harry Arlo Nimmo, an anthropologist who wrote about indigenous boats from the Philippines. He notes that the vinta is a houseboat, as indicated by the carvings in it (Nimmo 71). The boat is called by different names and by different groups. According to Nimmo, the “Bajau call this boat pilang, while the Tausug call it dapang” (Nimmo 87). These groups are located in the southern Sulu islands of the Philippines (Nimmo 52). He notes that the “Art (okil), as carving or painting, is reserved for houseboats”, though he additionally specifies that some fishing boats do have carvings (Nimmo 71). From these descriptions, one can infer that this model vinta is based on a houseboat. The carvings of the model are not as intricate as the object it represents, as vintas contained carved motifs of curved lines, leaves, flowers, and waves that were sometimes painted (Nimmo 73). This model is most likely a toy boat, as the design of the model seems too simple to mirror a houseboat. Toy boats were actually carved by the Bajau people and were often given to sons or made by young boys who held races using their toy boats (Nimmo 82). The way this object made its way to the museum most likely started with the item falling into the hands of a person of the American military and made its way across several individuals until it reached the Burke Museum. In Reynaldo Ileto’s article, “The Philippine-American War”, he notes that “Looting was rampant, as well, when nearly no one was around to protect their homes,” referring to the American military looting Filipino houses during the war (15). This looting is a likely explanation for how the boat fell into American hands.

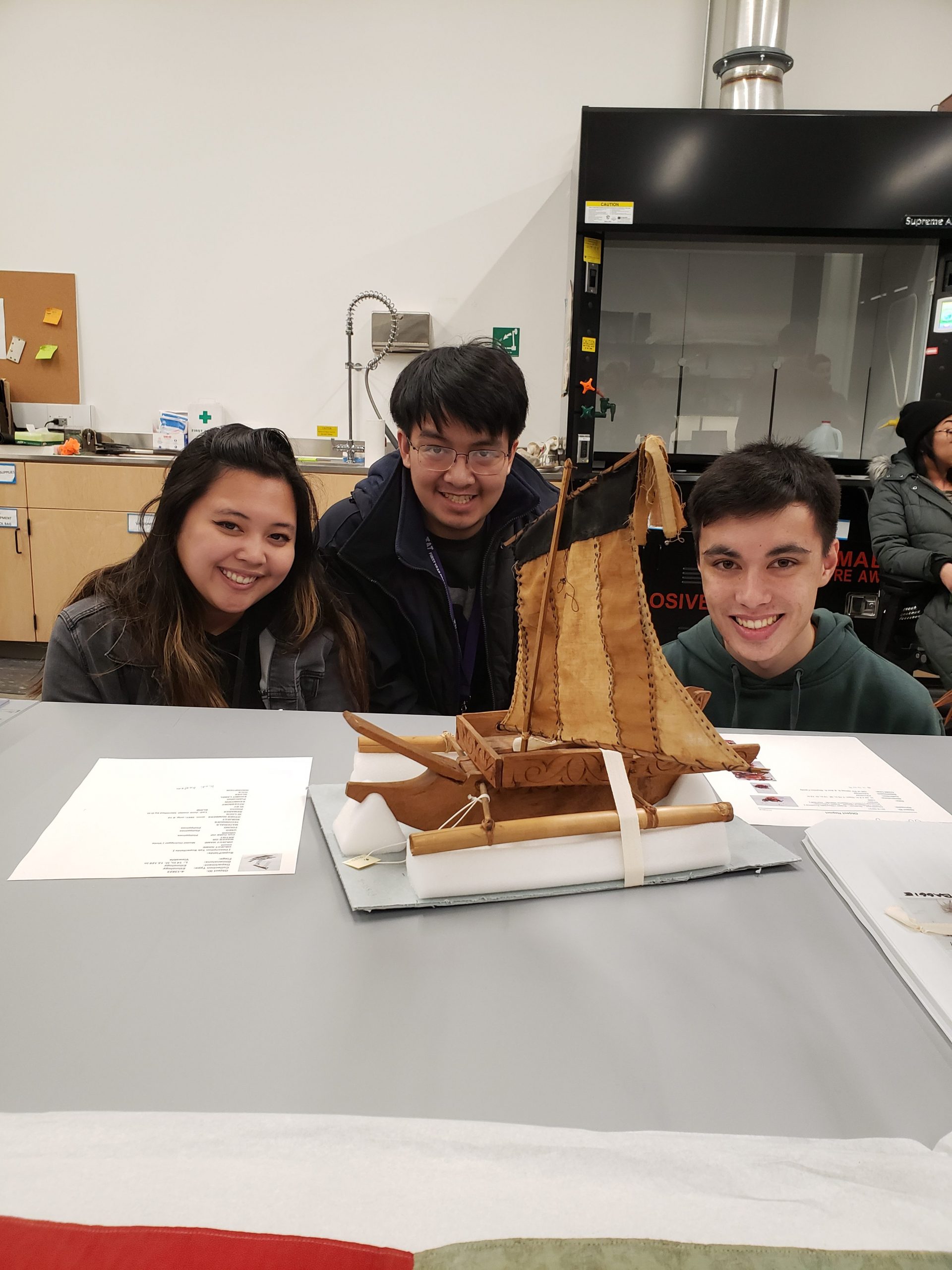

This artifact was chosen by Gabrielle Mangaser, a student who worked on studying the artifact in a group that also included Nathanael Ramos and me. The artifact was partially chosen due to its cute appearance as a toy. I was initially indifferent towards the artifact. However, as I learned about what the boat represented, I gained more interest in it. The rich culture of the Filipino groups that made vintas and their carvings represented a strong sense of culture that was only partially represented by this toy boat. However, if that was all I saw in the vinta, Steven De Castro would most likely call me a “junior coconut”, a type of Filipino that “thinks they can pick and choose which parts of the story they want to read” (De Castro 298). By not acknowledging everything the boat represents besides Filipino culture, a Filipino American observer may get stuck in a colonial mentality that De Castro warns about. This mentality forces the reader to ignore the trauma associated with this artifact by only acknowledging it as a splendid little boat. This idea spreads to a lot of items within the Burke Museum in that by only viewing them as memories of Filipino culture, the viewer forgets the pain it took for the artifacts to make it to the museum. The artifact represents more than just the culture of the Bajau people. It also expresses the traumatic violence and war waged against the people in the Philippines by the American army. The idea that this boat was most likely looted is something that is hidden when studying just the vintas that the toy is modeled after. The image of someone taking this boat from a child’s collection of toys is a symbol of trauma that potentially resides within this artifact.

When it comes to what resided in the artifact, I was less concerned with the trauma and more interested in the artistic culture that went into making the boats that the toy represented. This was not due to me not acknowledging the history of violence associated with the artifact. There was simply more information on the culture associated with vintas than there was on the exact history of the toy boat. This is most likely due to the nature of looting being an undocumented act that contributes to a history of forgetting that Ileto says is part of the ultimate surrendering that the Filipinos had to partake during the Philippine-American War (Ileto 19). As such, I found there was more to be fascinated with when it came to the artistic culture of the boat rather than its history of violence purely based on how much or how little information I could find. Of course, this fascination was only developed after doing heavy research into the object and vintas in general. The accessibility of reliable and authoritative information on Filipino cultures can often be difficult to navigate. Many young Filipino Americans I know will likely know very little about this artifact without doing similar research. Additionally, even if they were to research on this artifact, they would most likely find little about its tragic history and relation to the Philippine-American War. And this will continue on for the rest of their lives as they have very little incentive to learn about Filipino culture while here in America. However, perhaps, if they ever read this, they will change and seek to learn more about their Filipino heritage.

Nathanael Ramos

This artifact is a model vinta, a sailboat commonly used in the Mindanao region of the Philippines. It is a small narrow outrigger known for its decorative rectangular sails and creative hull design. While it is not built for rough water or long journeys, the vinta is a multi-use boat, and is used for short-distance transportation, fishing, tourist activities, and even housing. The Mindinao region of the Philippines covers a large area, so there are local variations in the vinta’s use and name. It is also referred to as a pelang, depang, lepa-lepa, sakayan, or bangka (Nimmo). Filipinos have often been categorized as Asian or Pacific Islanders, but even generalizing the use and names of the vinta in the Philippines does not give credit to local specificities within the Philippines. The artifact is currently stored at the Burke Museum in Seattle, Washington and, to our knowledge, its true origin and journey to America are unknown.

All the artifacts reflected upon in this book illustrate meaningful aspects of Philippine history and culture that are still relevant today. The identities of both the maker and the “owner” of the model vinta are expressed through creativity in the sail and hull design. The artifact itself has multiple identities. It is simultaneously a model, an artwork, a floating boat, a toy, an expression of identity, and a symbol of strength and resilience. Its interpretations are endless and demonstrates the thoughtfulness required for its presentation in a museum. The delicate model’s humble color and design are a symbol of resilience for a culture that has endured conquest and trauma. While a museum should provide historical context, it should in no way bias the viewer into limiting the artifact to just one identity.

The next step in this reflection is to investigate the artifact in the context of our class: Critical Filipino American Histories. As an engineering major, this class was very diversifying and a rewarding break from technical classes. Furthermore, I have not been able to connect with and engage in my own family’s history and culture quite like this since attending the UW. In this class, we read Filipino American essays, read an autobiographical novel, America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan, and watched a Filipino movie, Milan (2004), to learn about Filipino American history and to understand the diverse experiences and collective relationships of Filipinos.

One class reading, “Identity” by Carla Kaplan, provided a foundation for the class. The author states that “Identity is neither something we possess nor something that defines us but is an unending linguistic process of becoming.” She makes the distinction between personal identities and social identities (i.e. who we are versus who we are supposed to be). The model vinta itself demonstrates the changing nature of identities which depend on the history and the people. The artifact’s maker and the “owner” express aspects of their identity through the sail design, color schemes, and hull engravings. For these people and their families, the vinta may have sentimental value or fond memories associated with it. For Mindanao communities, the vinta symbolizes a common cultural artifact, but has the flexibility of different local designs, uses, and names, allowing many expressions of local identities.

Identity is important when studying the history of a group of people, but for Filipino Americans, their history and, therefore, identity have been affected by trauma due to colonization, conquest, and racism. Marie-Therese Sulit, in an essay titled “Through our Pinay Writings: Narrating Trauma, Embodying Recovery,” defines trauma, the paradoxes of trauma, and the routes to recovery by turning to what can be learned from Filipino American literature. She suggests writing and reading to help deal with trauma. For Filipinos, the vinta is a symbol of resilience and strength. A group called the Katatagan (meaning “stability” in Tagalog) is helping with Filipinos cope with surviving typhoon disasters (Hechanova). The participants were given a drawing of a vinta and were instructed to write their sources of external and internal strength on different stripes of the sail. As a group, they reflected on the ways these strengths could be used to assist in their (physical and emotional) recovery from the disaster. Community, personal strengths, and cultural symbols are all things Filipinos have leaned on to recover from a history of trauma and resistance.

The model vinta appealed to me because I have always been fascinated with model cars, boats, trains, and planes. My Filipino grandparents keep items of similar cultural significance in their house, including dolls, chairs, and tapestries. These keep them connected to their identity back home in the Philippines, while for me, Filipino artifacts remind me of fond memories and encourage me to appreciate and celebrate my family’s background. I enjoy fishing with my grandpa, so this model vinta reminds me of something that I trust with my life on the water, and symbolizes, for me, strength and security.

While I have published on Wikipedia, this is the first time I have published something with greater creative liberty and without anonymity. Initially, I felt pressure from myself to publish something extraordinary and powerful. But this reflection has taught me that what is most important is speaking honestly from the heart. What I want people to take away from my reflection is the idea that there is more meaning beyond the physicality of an object. These artifacts are creative expressions of identities and sources of preservation of history and culture that must not be forgotten.

Gabbie Mangaser

Artifact Analysis and Reflection

The vinta artifact from the Burke Museum is a model of a much larger outrigger boat used mainly in the city of Zamboanga, Mindanao in the Sulu Archipelago. Known to locals as lepa-lepa, or sakayans, it is used by the Moros, and the Sama-Bajau peoples. When we think of the Philippines, we often do not put forth much thought into its Muslim history when, in fact, much of pre-colonial history begins here. The Philippines, before it was named Las Islas Filipinas by the Spanish, was a conglomerate of sultanates. The vinta during this time was used for traveling and fishing, and now its use mostly caters towards tourism. Its distinction from other bancas in the Philippines lays in its supposedly colorful sails.

Though the artifact itself is a Philippine artifact rather than a Filipino artifact, there are very important points to be made. I believe it is important to note that although it is mainly used for the purpose of commercialization through tourism, its use surpasses that of colonialism. This is a boat from pre-colonial times used by indigenous peoples of Mindanao, and despite both Spanish colonization and United States imperialism, it is both a product of history as well as a tool of the present. It represents the resilience of the Filipino, through adaptability.

The model vinta is also a symbol of multiplicity in the Filipino identity. In the poem “Conditions” by Napoleon Lustre, he illustrates that there is no single definition that makes one Filipino, because there are all kinds of stories that connect Filipino to Filipino:

You are Pilipino

if your mother is Pilipina

if your father is Pilipino

if you are from ‘pinas

if you have one drop of Pilipino blood…

You are Pilipino

if you are descended from the children

of the Spanish friars, priests, and other unholy men…

You are Pilipino

it doesn’t matter if you’ve been whitewashed by blood or culture…

You are Pilipino

if you are 1/2 Mexican, 1/2 Flip…

Because it is one type of Philippine boat, it can be a symbol of just one of the many identities that the Filipino can have. For example, take the Philippine paraw used in the Visayan region. Its original use was for the Palawans to fish and for transportation. The original boats were not always made out of the same materials like the vinta and the paraw, further contributing to the idea that identity is of multiple origins and complex histories.

Much like how there are many origin stories, there are also many destinations for Filipinos. The model vinta represents the journeys that millions of Filipinos have taken from their homeland to find a better life, such as the ones experienced by overseas Filipino workers (OFWs). It can represent the stories of Filipinos petitioning for their families to come to the United States. It can exemplify the stories of the Filipinos who have traveled away from their homeland and the hope they have to return one day. Though we may not have the tools to accurately pinpoint where this artifact came from in the Philippines, it is clear that it has made a long way to journey into the Burke Museum in Seattle.

The Role of the Museum and Self-Reflection

As a Filipina, it is encouraging to see more Philippine history in the light through these artifacts. When we think of Asian and Asian American histories, many fail to look past the hegemonic contexts from China and Japan and less into histories of Southeast Asia and their people. Courses that study Filipino histories are the beginning of a new turn in academics that can shed light on more holistic Asian perspectives. However, we could do well to recognize the role of the museum in knowledge production as well as the ownership of artifacts. Academics should remain critical of how artifacts are portrayed and organized within a system, and keep in mind that one artifact does not completely and perfectly summarize an entire culture. The vinta has the ability to personify Filipino identities and their journeys, but knowledge surrounding artifacts do not end at a certain point. Like identities being ongoing processes, so is the production of knowledge.

Growing up in a family of Philippine immigrants, I never took pride in what it meant to be Filipino until half-way through my undergraduate studies. Even then, it was the lack of Asian Americans in general in the subjects I wanted to study—both as topics of discussion and as faculty—that inspired me to become more interested and start asking questions as to why this was a regular occurrence. This project has made me hopeful for the future of Filipino and Filipino American Studies to have adequate representation within academia.

Works Cited

De Castro, Steven. “Identity in Action: A Filipino American’s Perspective.” The State of Asian

America: Activism and Resistance in the 1990s, edited by Karin Aguilar-San Juan, South End Press, 1994, pp. 205-320.

Hechanova et. al. (2015). The Development and Initial Evaluation of Katatagan: A Resilience

Intervention for Filipino Disaster Survivors. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 48 (2), 105-131.

Ileto, Reynaldo C. “The Philippine-American War: Friendship and Forgetting.” Vestiges of War The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream 1899 – 1999, edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia, New York University Press, 2002, pp. 3-20.

Kaplan, Carla. “Identity.” Keywords: For American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler, New York University Press, 2007, pp. 123-127.

Lustre, Napoleon. “Conditions”. Amerasia Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2, 1998.

Nimmo, H. A. (1990). The Boats of the Tawi-Tawi Bajau, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines. Asian

Perspectives. 29 (1), 51–88.

Sulit, Marie-Therese. “Through Our Pinay Writings: Narrating Trauma, Embodying Recovery.” Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory: Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience, edited by Melinda L. de Jesús, Routledge, 2005, pp. 351-371.