7 Indigenous Innovation: Poison Bow and Arrow Set

Danica Villez

by Danica Villez, Isabella Dalmacio, and Matt Berhe

Society has always been fixated on making things better. We want bolder, newer, more complex and efficient things, and while the desire for these upgrades isn’t necessarily bad, it often renders their predecessors as primitive or irrelevant. However, it’s so important for us to understand the artifacts of the past, because only in doing so can we understand the developments of the present.

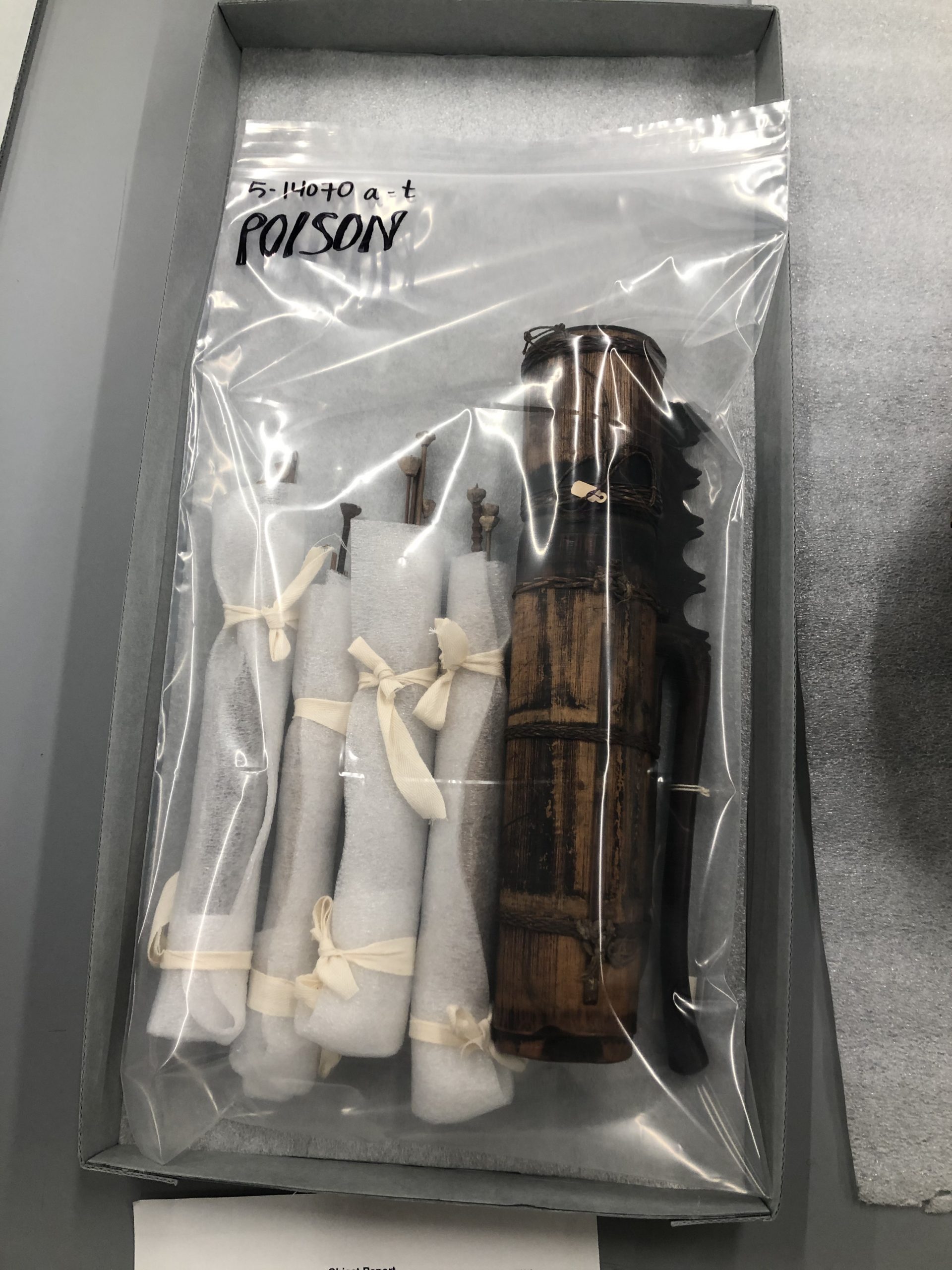

Our group chose to research a poison bow and arrow set, complete with a quiver and lid. They were dated from before 1915 and sourced from the Philippine Islands, sealed away in a bag for safety purposes, as the poison was potentially still potent. Upon our initial research, we discovered that these arrows were likely used for hunting, fighting and warfare. While arrows were often used in battle throughout history, the use of poisoned arrows was practiced widely in pre-colonial times. Using poison made of plant, animal and/or insect extracts, hunters and warriors would lace their arrows with these toxins so that they may have a second line of defense against their prey or enemies. If the arrow would not be enough to kill them, the poison would work its way through their bodies and they would die by touch or smell. The process of creating these poisons was very meticulous, from pressing and heating the sources of these toxins, to extracting and applying them to their weapons.

Poisoned weaponry is not an unfamiliar concept to us. From Greek warrior Achilles being shot in the ankle with a poison arrow to the shocking death of The Mountain in the HBO show Game of Thrones, there have been many stories of poisoned weaponry as an effective and strategic tool. However, these are merely stories; we’re conditioned to see them as otherworldly, mythological, and anachronistic. It isn’t widely known that these weapons are integral to the history of many cultures, including Filipinx culture. Not only were poisoned bows and arrows used for hunting food, they were also used in amigo warfare, a term coined by historian Reynaldo Ileto to describe the ways in which Filipinos used stealth tactics and feigned friendship to discreetly fight against oppression and colonization. If a Filipinx warrior shot someone with a poisoned arrow but removed it before their enemy’s body was discovered, the cause of death could not be traced back to them. This is an example of Filipinx resilience and resistance that have connected our ancestors together long before our artifact’s dated year. In fact, a poisoned arrow is said to be the weapon that our first Filipino hero Lapu-Lapu used to kill Magellan and his Spanish colonizers in the Battle of Mactan. This bow and arrow exemplify our culture’s strength and skill, but it is not often honored as such. When we are taught about native warriors in history today, our weapons are depicted as savage and barbaric. Our ingenuity is invisible to our historical gatekeepers. Our ancestors are called uncivilized.

To our group, this artifact represents how resourceful and knowledgeable Filipinx people were and are of their land. It represents indigenous innovation, a narrative that has been changed and concealed by U.S. imperialism and the colonization of our education. To Danica, this weapon represents Filipino resiliency, the action of fighting back against the oppressor that is rarely seen in media. For Matt, this artifact represents indigenous people’s resourcefulness and knowledge about their environment. It defeats the narrative of incompetent savages. To Isabella, this weapon represents the Katipunan, Filipinx revolutionaries who used bows and arrows, amongst other weapons, against Spanish colonization. These warriors are her namesake, and her source of inspiration and power.

Society has always been fixated on making things better. However, development doesn’t beget progress; knowledge does. It isn’t enough to innovate and expand if we cannot honor and educate ourselves on the things of the past. This Open Textbook Artifact Project allowed our group to do that. We found ourselves drawing parallels from our past to our present: eco-friendly “innovations” used by indigenous folks but claimed by white society upon their discovery, and indigenous culture and tradition exploited on social media videos that receive comments denouncing them as third worldly, sad, and savage. We learned so much about the inherent power of our ancestors, a strength that we carry within ourselves and our communities. We also learned that asking to open a bag of poisoned arrows to get a closer look is maybe a bad idea.

In closing, we’d like to first and foremost recognize the stewards of Coast Salish lands, original and current caretakers from the Duwamish, Suquamish, Tulalip and Muckleshoot peoples, on whose lands we reside and study today. Our hands go up and recognition spreads. Secondly, we’d like to acknowledge the indigenous people of the Philippines whose artifacts and histories we have discovered through this project and this class. We’d like to additionally thank Dr. Holly Barker (Curator for Oceanic and Asian Culture and Principal Lecturer with the Department of Anthropology), Kathy Dougherty (Collections Manager, Oceanic and Asian Culture), and Rose Mathison (Collections Assistant) for helping facilitate this project and expanding our learning through the Burke Museum and its artifacts. We’d like to thank Professor Bonus for being our engaging and enthusiastic professor, and always encouraging us to “search, discover, reclaim.” We’d like to thank our classmates for being open-minded and kind throughout the quarter. Finally, to our families and friends, thank you for the love and support. Mahal na mahal namin kayo.