Challenging Encounters

Physicians experience up to one in six visits as ‘challenging’, taking a disproportionate amount of time and emotional energy, causing anxiety or frustration, and compromising our ability to provide good care. Patients may feel just as frustrated and dissatisfied as their doctors, damaging therapeutic relationships, seeding distrust and leading them to seek more second opinions and emergency department care.

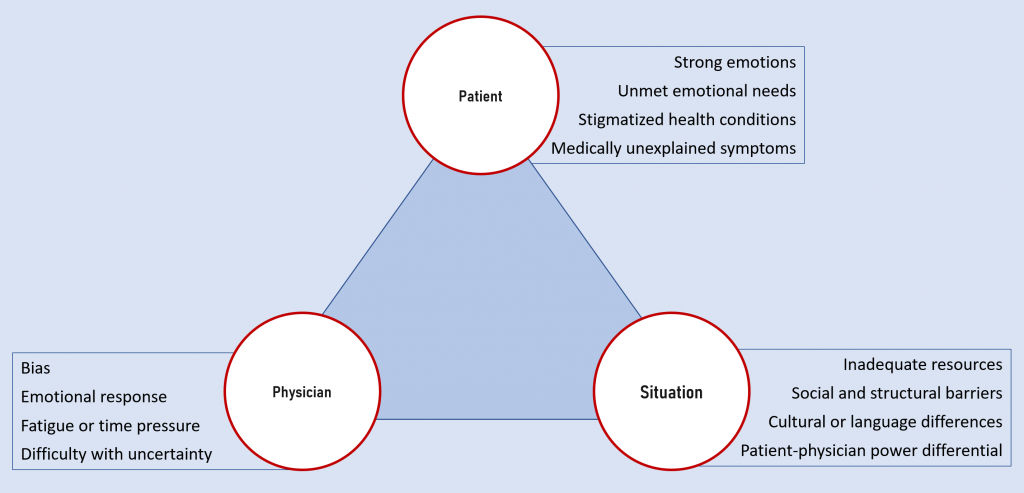

Challenging encounters are usually caused by a complex interplay of physician, patient and situational variables. Recognizing this complexity, we encourage you to explicitly consider each of these. Regardless of specialty, almost all of us will experience challenging encounters throughout our career – learning to navigate them well is critical to maintaining our joy in the practice of medicine

Physician factors

The variable that you, as the clinician, have the most control over is yourself. Whenever you feel upset or uncomfortable with a patient, start by examining the emotions and biases that you may bring to the encounter. Countertransference was first described by psychoanalysts but can affect any patient-provider relationship. The clinician unconsciously projects feelings from a different personal or professional relationship onto the patient. Does this patient remind you of a family member, previous patient, or someone you had difficulty with in the past? If you are feeling fatigued, stressed, or burnt out are you attributing these feelings to the patient’s behavior rather than addressing them in yourself?

Clinician biases can affect every step of a clinical encounter from initial rapport building to developing a plan together. Our patients’ identities, interactional styles, beliefs and values may differ fundamentally from our own. To provide good care, we need to know ourselves first and practice cultural humility when engaging with others. Pay attention to the clinical scenarios that are particularly emotional or triggering for you. These are different for different physicians, but often include uncertainty, serious illness, chronic pain management, substance use disorders, abuse or neglect, or multiple unexplained symptoms. Learn what your triggers may be and work to find ways to treat your patients equitably and respectfully

Patient factors

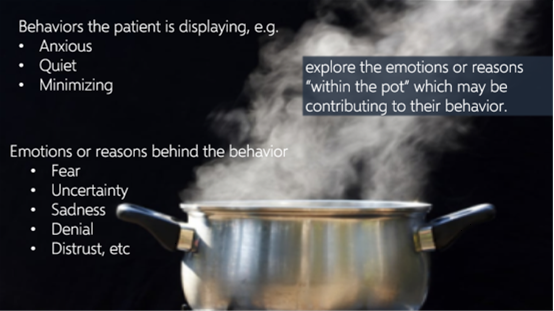

Patients also bring many things to an encounter, some of which we recognize but many of which we do not. Acute and chronic health issues are inherently stressful for most people. Mood disorders such as depression or anxiety, language or cultural barriers, and mistrust of the healthcare system caused by past mistreatment can all interfere with the development of a therapeutic relationship. Patients’ interactional styles may also be quite different from our own. These underlying emotions, stressors or barriers may manifest in many different types of displayed behaviors. We may perceive a patient as angry, defensive, resistant, anxious, withdrawn, or in denial. But what lies behind what we see? Curiosity and a willingness to explore the underlying reasons often lead to a better understanding and improved communication.

Situational and structural factors

Situational and structural factors also play into the mix. Physicians and patients may have different agendas. Financial and insurance barriers may limit the resources available, and short clinic visits, language and cultural differences, time pressures and frequent interruptions or suboptimal EHR use can get in the way of connection.

The power differential inherent to the doctor patient relationship can also contribute, placing us in a position of authority over patients who may feel quite vulnerable and out of control. They may try to increase their sense of control through their decisions to adhere or not adhere to our recommendations, or through behavioral expressions, like anger, boundary crossing, or showing up late. When you find yourself in a challenging encounter, consider the possibility of a power struggle or disconnect between your and your patient.

Tools for navigating challenging encounters

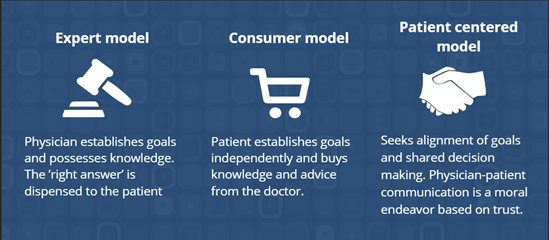

Stay patient centered: The three commonly accepted models of patient-physician interactions are the expert model, the consumer model, and the patient-centered model. They differ primarily in how power is distributed between the participants, although it’s important to remember that the physician-patient relationship is inherently unequal.

The practice of relationship-centered care allows patient and provider to share a mutual understanding of values, goals and expectations and can lessen the power differential. The provider uses collaboration strategies to align with the patient, like agenda setting, a guiding communication style, boundary setting when appropriate, exploring emotions and displaying empathy.

Mindfulness and Reflection Skills

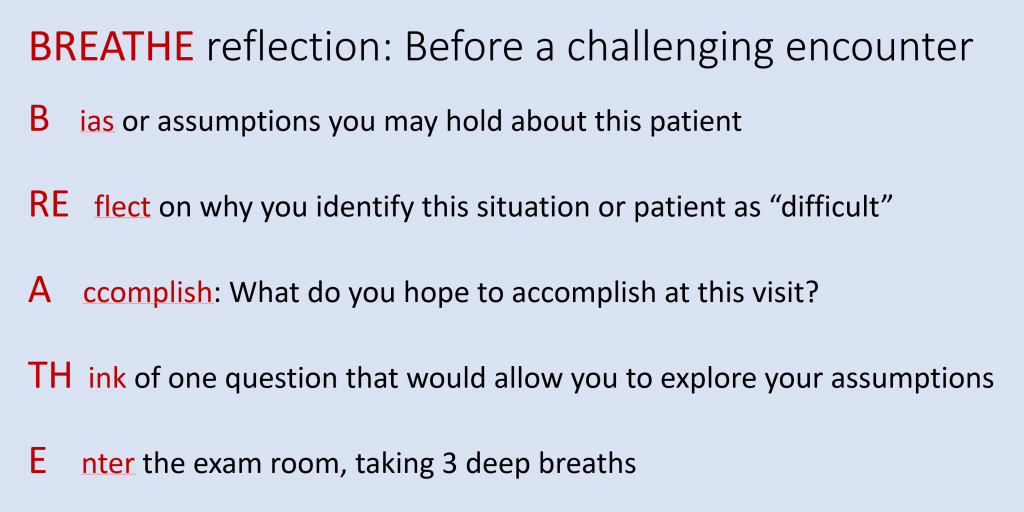

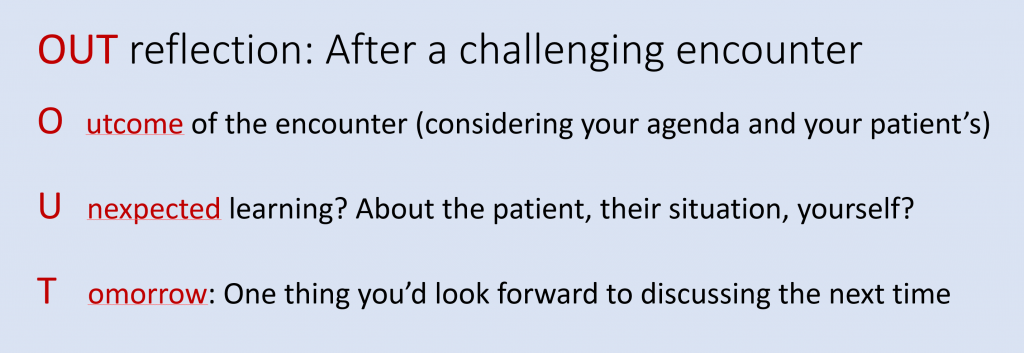

Mindful practice can help to prepare clinicians for encounters they anticipate may be challenging and to reflect afterwards on WHY.

One family medicine residency practice developed a structured reflection tool, BREATHE-OUT, for use before and after a challenging clinical encounter and found that it improved clinician satisfaction with these visits. If you anticipate an encounter may be challenging or you may leave a clinical encounter having felt particularly challenged, try using BREATHE-OUT to help process these interactions and to continue to build your mindfulness toolbox.

Caring for patients can be highly rewarding and can also at be times stressful or hurtful. Most clinical encounters go smoothly, but some may involve microaggressions, biased comments or assaults toward you, your colleagues or your educators. As we discussed in Immersion, we feel that it is important to acknowledge that these encounters will occur and to empower you with different tools and ways to potentially respond. We encourage you to revisit the chapter on Responding to Microaggressions for some potential approaches.

With time pressures and our own feelings triggered by challenging encounters it can be hard to maintain compassion for patients. Data support that when providers bring empathy and compassion to clinical encounters it can improve physical and psychological health outcomes for patients, reduce physician burnout and lead to increased happiness and fulfillment in their careers. Even 40 seconds of compassion can make a difference! “We’ve always heard that burnout crushes compassion. It’s probably more likely that those people with low compassion, those are the ones that are predisposed to burnout.” If you are interested in learning more you can explore this link to an NPR article summarizing the work of Trzeciak and Mazzarelli in their book Compassionomics: The Revolutionary Scientific Evidence that Caring Makes a Difference.

Resources and references

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The Patient, the Physician, or the Relationship: Who or What Is “Difficult”, Exactly? an Approach for Managing Conflicts between Patients and Physicians “2279 (nih.gov)

American Family Physician. How to Manage Difficult Patient Encounters.

American Family Physician. Managing Difficult Encounters: Understanding Physician, Patient, and Situational Factors.

J Am Board of Family Med. BREATHE OUT: a randomized controlled trial of a structured intervention to improve clinician satisfaction with “difficult” visits

Journal of General Internal Medicine. A Cohort Study Assessing Difficult Patient Encounters in a Walk-In Primary Care Clinic, Predictors and Outcomes. JGIM 2011; 26(6): 588–94.

Responding to strong emotion

Strong emotions, including anger and frustration, are common in the clinical setting. Fear, feeling sick, loss of control, frustrating gaps in the health care system, and disrupted schedules & sleep can all contribute to a short fuse. Sometimes strong emotions can disrupt care and pose a threat to both the patient and to the provider.

It is important to pay attention to warning signs that something is wrong. There are many signs that patients may be angry: clenched fists, furrowed brow, hand wringing, pacing, raised voice, restricted breathing patterns, etc. Once these signs are recognized it is important to avoid being drawn into conflict. In these moments it is imperative that we take a pause and recognize our triggers and be careful not to respond with anger. Instead make sure to keep yourself safe, identify your boundaries and try to uncover the source of difficulty for the patient. De-escalation techniques are important such as using “I” statements to acknowledge their anger and working toward ways to resolve the situation. “I can understand why you are upset. Can we talk about ways to fix the situation?” Also remember that a sincere apology can go a long way to rectifying a relationship.

Using techniques to empathize with the patient may help to create a more constructive connection between you and the patient. Think back to the boiling pot analogy discussed in the chapter Delivering Serious News, the displayed behavior may be anger however the deeper emotion may be something else (fear, loss of control, etc.). Exploring and acknowledging the deeper emotion may help you and the patient align and work together to address the issue.

Screen reader friendly version of the above graphic available here.

We must also look at the factors that we bring to the encounter. Time pressures, stress, sleep deprivation, burnout and many other issues may weigh heavy on us. Recognizing the personal baggage we bring into the room is important. Finding time for ourselves and loved ones and developing personal practices which may address these stressors are important to help foster a healthy environment for patients and ourselves. When these issues are impacting the encounter in the moment, take a pause and practice a brief moment of mindfulness before engaging with your patient. Consider HALTing and assessing your needs in the moment. Am I Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired? Can any of these issues be addressed right now or soon? Remember to STOP before continuing with the patient encounter.

Stop. Pause, just for a moment.

Take a breath. Center yourself and regroup.

Observe. What is happening? How might you respond more constructively?

Proceed

When strong emotion enters a clinical encounter, these strategies can help to de-escalate the situation and keep everyone safe.

Watch the following video for a deeper discussion on how to de-escalate situations.

Strategies to help with de-escalation

- Listen closely and actively. Reflect what you heard, request and accept corrections. Did I get that right?

- Identify and validate wants and feelings and try to accommodate reasonable requests

- Apologize if possible

- Be mindful of personal space – maintain two arms length between you and your patient and a clear path to the door for both of you.

- Be concise. Cognitive function is impaired when people are upset or angry – the prefrontal cortex shuts down and the ‘fight or flight’ amygdala takes over.

- Stay calm, in control, and measured. Our natural reaction is to reflect the emotion expressed to us – AVOID returning anger for anger.

- Offer choices and optimism

- Set limits but don’t order specific behavior

- Find common ground – agree or agree to disagree, while avoiding negative statements. This validates what the patient is saying and puts you on the same side.

- Debrief with your team or a colleague afterwards

(Optional) Additional videos on de-escalation techniques

- How to identify and prepare to meet with a disruptive patient

- 21 phrases to help de-escalate patients

- Actions to avoid. Actions to take. Documentation of the encounter.

Knowledge check

Watch the following video of a patient encounter that did not go well. As you are watching, jot down some thoughts on moments when the doctor could have pivoted and utilized some of the de-escalation techniques discussed above.

Redirecting & focusing

Patients and providers feel stressed when they don’t have enough time to accomplish their goals for the visit. Time management strategies are especially important when patients are very talkative or tangential.

When interacting with a talkative or tangential patient taking time to try and understand why this may be happening can guide the techniques you use during the encounter. This may be your patient’s typical communication style or maybe the patient is feeling nervous, anxious or worried. Spending time getting to know the patient and their needs can guide the communication techniques which may be most effective.

Assuming the medical issue is not imminently life threatening, consider changing the goal of the interaction to address emotional needs first with the plan of having the patient return soon to further discuss the medical details.

Traditional teaching around patient-centered communication emphasizes the use of open-ended questions, invitations to share in an uninterrupted way, active listening and eventually moving toward more directed, closed ended questions. This technique may be less effective with talkative and tangential patients. Finding a way to continue to listen actively and empathically while obtaining information efficiently is important. Taking a more directed approach to information gathering is often necessary.

Agenda setting early on is a helpful technique . Before exploring a particular concern elicit a comprehensive list of patient concerns (without allowing them to dive deep into details at this point) and then spend time negotiating up front which issues can be addressed adequately and safely during the time you have together. Acknowledge upfront the need for follow up visits to further address their other concerns. Although one may worry that the use of agenda setting will length an encounter, studies have shown that providers who use an establishing focus protocol do not lengthen the time of the visit and patients are more satisfied and perceive that more of their concerns were elicited and prioritized. If you are interested in learning more about agenda setting feel free to read this article.

Aligning with the patient early on by asking them to share the responsibility of effective time management can be helpful. “Today we have decided to focus on these two issues. I am hoping we can work together to stay focused on these two issues so I can get the information needed to provide you good care.” You may need to remind the patient of this agreement if the conversation goes off track. Agenda setting and sharing the responsibility of maintaining focus and efficiency may help patients learn to prioritize and structure their information for future encounters.

Rather than remaining too open-ended in your questioning try tailoring your approach to include subtle strategies such as reformulating the question, listing several options, specifying the type of answer needed or clarifying the purpose of a question. If this does not work you may need to be even more directive and explicit in the information that you need and transition to using closed-ended questioning techniques.

The use of summary statements can help to clarify details that may have been challenging to follow. Making the subtle adjustment of providing a ‘closed-ended’ rather then ‘open-ended’ summary can clarify details while trying to avoid patient interruptions and the invitation to share more details unless absolutely needed.

Sometimes despite all these techniques, the provider will still need to interrupt. Empathic interrupting lets the patient know that you take the problem seriously while enabling you to refocus the attention on the current problem. Non-verbal gestures may be used to create this interruption however it is important to recognize that we do not all share the same interpretations of certain gestures and they may not be understood or appreciated. Use them mindfully and with caution. You may need to be more explicit. “What you just brought up is really important. Shall we get to that topic next week when I see you back in clinic. I would like to continue to address X at this time so we can get you the care you need.”

With the use of these techniques you can work toward creating a therapeutic space for both patient and provider.

Tools to use to redirect and focus

- Collaborate to set the agenda. This is important for all visits but it’s critical for people who tend to be talkative. If you establish the goals and the time available at the start, you can refer back to the agenda if you need to redirect or interrupt.

- Thank you for that list of questions and concerns. In the time we have together today, I think we can do a good job on 2 or 3 of them. Let’s schedule a follow up visit so we can address the others soon.

- I can see that’s important, but I’m afraid if we spend time on it now we won’t get to…

- Reflection & summary: A patient who is talking at length may be signaling that the topic is emotionally important to them. Acknowledging that you’ve heard them with reflection & summary can help move the conversation forward.

- Redirection: When a patient is loquacious or tangential, it’s an appropriate use of power to bring them back to the reason for the visit. Respond to something they’ve said when they pause to breathe, then ask if you can change direction.

- I appreciate hearing about that – would you mind if I move us back to the cough?

- Non-verbals: Generally, in our culture, if you look the speaker in the eye and smile or clear your throat most people will recognize that you wish to speak. Try this first! Physical gestures like holding up a hand or a brief touch on the arm or hand can be used to interrupt a long narrative, but use with caution and respect.

- Verbal interruption: Just like different people have different notions of what constitutes adequate personal space, we have different notions of how long a pause is needed before another can begin speaking without being impolite. Watch your patient’s response and cues, and modify your approach as needed.

- I’m sorry for interrupting but I want to be sure I understand…

- Change question type: You can also try using more closed ended questions to elicit important details more concisely

Resources and References

Professional boundaries

Patients may push boundaries in a number of ways. Unreasonable demands or expectations or a blurring of the lines of the physician-patient relationship can occur. There are many other ways in which patients can challenge boundaries. There are many reasons why patients challenge boundaries. These may include seeking support, attempts at shifting the power differential, discomfort with the patient role or health care environment, looking for special favors, embarrassment, distrust or self-advocating among others. Mental health, cognitive or substance use issues may also contribute.

Regardless of the reason, checking our biases first and then utilizing some of the following approaches may help develop the therapeutic relationship and allow the patient to receive appropriate care.

It is important to spend some time developing rapport with patients and learning how to make connection. Finding the balance between being personable and professional is the goal. When the conversation begins to migrate away from the patient’s issues and starts to focus on you this may be a time to re-establish boundaries and redirect the encounter.

Be transparent in expected norms around doctor-patient relationships. Utilize evidence-based diagnostic and treatment recommendations rather than emotional responses to make care decisions. Let the patient know it is important that they receive the most appropriate care.

When appropriate, explore potential reasons for their behavior with the patient. Reinforce how joint decision making will GIVE the patient a modicum of control.

Acknowledge the uniqueness of a doctor-patient relationship and how this can be unfamiliar or uncomfortable at first. Emphasize your professional role in the relationship. Talk about the patient, not yourself – redirect the patient when they try to bring the conversation back to you.

You may need to impose structure returning to the health care issues at hand and continuing to use evidence-based and clinical experience to guide your decisions. Sometime you may have to rely upon and share protocols about appropriate physician-patient interactions. Learn to set limits and be explicit. Remember to keep you and the patient safe and consider inviting a chaperone for any sensitive exams or conversations.

Approaches to working with patients who push boundaries

-

- Be transparent

-

- Model appropriate behavior

- Emphasize your professional role in the relationship

- Redirect the conversation back to the patient.

- “I’d like to keep the focus on you today so we can best care for you.”

- [more assertive] “I don’t feel comfortable bringing those personal details into our visit today. Let’s stay focused on you.”

-

- Impose structure, keep returning to the health care issues

- Utilize evidence-based and clinical experience to guide decisions

- “I can understand that you would like a sleeping pill (Ambien) just in case you have back pain so you can sleep however the evidence does not support any benefit of Ambien for the treatment of back pain and has potential risks”

- If necessary, rely upon and share protocols for physician-patient encounters

- “We’re actually not allowed to have social relationships with the patients we see in clinic, but I’m happy to be part of your care team here.”

- Set limits, this may need to be done repeatedly

- “As I said before, I really can’t answer personal questions.”

- Be explicit, explain that you feel uncomfortable

- Utilize a chaperone if available

Multiple Concerns or Medically Unexplained Symptoms

Medically unexplained symptoms are defined as symptoms that patients experience which impair function but do not fit characteristic patterns of disease, and persist despite normal examinations and investigations. Most studies suggest that more than 50% of patients visiting primary care clinics with physical symptoms have no diagnosable organic disease. As you can imagine, these scenarios can be incredibly troubling for patients and providers.

Patients with MUS often describe multiple symptoms, require frequent clinic or emergency department visits, frequently engage with the clinic outside of visit times (phone calls, electronic communication, letters, etc.), “doctor shop”, or request multiple diagnostic tests or treatments. With time limitations and heavy work loads, physicians may feel overwhelmed by these concerns and requests.

Patients may not feel heard or cared for if their issues are not addressed and in some cases may be harmed by unhelpful investigations, inappropriate interventions or medications. Ensuring that the patient has received a comprehensive history and examination and reviewing past diagnostic tests and treatments is imperative to ensure that an organic cause of their symptoms has not be overlooked. Remember to explore any attributions the patient may have regarding the cause of their symptoms. In some cases, additional testing or referrals may be appropriate. As a physician, when we are faced with uncertainty this is the time when curiosity and further exploration is even more important. It is also important to consider other possible reasons why a patient may present in this manner. Acknowledging and addressing these issues when identified may help with healing. Whether these factors may have contributed to or resulted from the illness is less important than recognizing that without support in these areas healing is more difficult.

- Received inadequate or inappropriate care in the past

- Fear of serious illness

- Feeling that unless they are “really sick” they may not be taken seriously

- Stress or comorbid anxiety, depression, personality disorders

- Inadequate social support, loneliness, isolation

- Fear of abandonment

- Intimate partner violence

Patients with MUS often feel that physicians do not believe that their symptoms are real or that they may be “all in their head.” Acknowledging and validating up front how difficult this must be for them and describing their symptoms and diagnoses with compassion can help to develop trust. Creating a therapeutic relationship by recognizing that their symptoms are real and troubling for them even if an explanation has not and may not be found is affirming. It is important to remember that healing can happen even if there is no cure. Pausing to reflect on why patients may have MUS helps providers maintain empathy, prevent burnout and bring meaning to the practice of medicine.

Setting the expectation of frequent, regular visits can help the patient feel heard and supported. Regular visits with agenda setting up front may allow patients to feel they don’t need to share everything at one visit. It may also prevent the development (conscious or unconscious) of new symptoms in order to obtain care since they know they will have the opportunity to see you again soon. As their physician, commit to your patient that you will continue to listen for information that requires additional medical evaluation and ensure them that you will pursue diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in those cases. Contract with your patient that you will see them often enough that these situations should not be missed while also asking them to understand that you will not pursue unnecessary tests that are unlikely to yield more information but may cause harm.

It is important to let patients know that even if you may not be able to give them a specific diagnosis to explain their symptoms that does not mean you can not help them feel better. Focusing on improving function and quality of life is important. Learning language that acknowledges and validates their suffering while also focusing on improving symptoms and function is helpful.

- “You and I have reviewed all of your previous tests and we have conducted many additional tests to evaluate your symptoms. At this time, we do not have a unifying diagnosis that gives a name to the symptoms you are experiencing. That does not mean you are not suffering. I think it is now time for us to start focusing on how to make you feel better and improve your quality of life. It is my job to keep watching out for signs and symptoms that something more serious may be going on which could require additional testing. My hope is that you can focus on healing through some of the treatments we will discuss today .”

Treatments may be tailored to the specific symptoms they display and/or may address other underlying comorbid disorders such as stress, anxiety or depression. A multimodal team approach involving medications, physical therapy, exercise, and mindfulness based approaches often work best. In some cases formal cognitive behavioral therapy is needed. Remember that health and healing is a continuum. Remaining engaged and supportive throughout the process and being open to new and different strategies is helpful.

Techniques that may help when patients have multiple concerns or medically unexplained symptoms

- Try to set an agenda early on in the visit

- Recognize that you will be unable to address all concerns at one visit. Practice the language of agenda setting and aligning goals.

- Agree that you will work together to determine what would be comprehensive and appropriate care.

- Remind the patient that it is important to you to make sure that they stay safe and healthy

- Emphasize that regularly scheduled visits will be helpful to mitigating their concerns. This may also help to limit communication and requests outside of visit times.

- Avoid suggesting that it is “all in their head” while still making sure to effectively manage any comorbid psychological conditions.

- Acknowledge how challenging it must be to be feeling so poorly

- Describe the patient’s diagnosis with compassion

- Acknowledge their dedication to their health

- Address some of your concerns up front with empathy.

- “I noticed that you have seen several physicians and have had extensive medical tests to try to uncover the cause of your symptoms. I recognize that these symptoms are very real and troubling to you. I believe that you have received a very thorough evaluation and these tests have ruled out any serious medical condition. I think it will be helpful for us to schedule frequent appointments every 2-4 weeks. This will allow me to see you often enough to discuss whether a further workup is necessary if something significant develops AND it will allow me to provide you some assurance that we are not missing anything.”

While considering how to care for our patients it is also important to care for ourselves. Practicing some of the previously introduced mindfulness approaches of BREATHE-OUT and STOP are helpful in these moments.

There are many times in medical practice when we will be uncertain. Did I get an adequate history? Did I interpret the medical information correctly? Did I miss a diagnosis? Am I adequately managing these complex medical conditions? Medical uncertainty is an innate feature of medicine and medical practice and an intolerance to uncertainty increases physician’s stress, contributes to burnout and may be a potential threat to patient safety. Medical uncertainty can be especially troubling to trainees as it is often believed that certainty is a necessary precursor for action.

Taking time to acknowledge how hard it may be to sit in a place of uncertainty is important. Learning to become comfortable with uncertainty rather than shying away from it allows us to stay present with our patients and to reflect on these moments as opportunities for learning and connection rather than a demonstrations of failure. We will be discussing the concept of uncertainty further during the upcoming workshop.

RESOURCES AND REFERENCES

Reserved patients

When working with quiet or reserved patients assumptions can be made that the patient is disengaged, avoidant or closed off. Obtaining information from reserved patients can be challenging and the risk is that deeper exploration may not happen. Although it may just be the patient’s personality or communication style, there may also be other reasons behind their displayed behavior. These may include but are not limited to:

- Fear of receiving a serious diagnosis or illness

- Lack of trust in the medical establishment

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, incompetence, shame

- Loneliness, social isolation, depression

- Denial

- Fear of abandonment

- Life stress

- Cultural norms

- Low medical literacy

- Language issues

- Memory disorder

- Concern about personal safety: at home, on the street, other

- Past abuse, sexual or other

Take your time and build rapport. That may be all you get done this visit and that is a lot. The best friend of the primary care physician (and any physician with a continuity relationships) is the next appointment.

In the vast majority of cases you will be very well served by asking open-ended questions. With a patient like this, you may need to use more focused, closed-ended questions earlier in the encounter. Remember that silence can be a gift. Most of us are uncomfortable with silence and we tend to fill the space. This is often because we are addressing our own anxieties. Sitting in silence with empathy and curiosity may allow a patient to ease into the conversation and share more.

Consider whether cognitive issues could be at play. Perhaps the history is better obtained from a family member or friend.

Acknowledging that the interview is difficult for the patient and for you. “I’d really like to be able to help you today, and I’m having trouble getting a sense of what brought you in.” Consider “floating a hypothesis” about why the interaction may be challenging based on what you have been considering as potential underlying emotions or factors. “I wonder if this is hard to talk about (the weight loss) because you are really concerned something serious is going on?”

Be open with the patient that you want to develop a trusting relationship. It may take time.

Techniques that may help foster a therapeutic relationship

- Take your time and build rapport.

- Use more focused, closed-ended questions earlier in the encounter.

- Consider whether cognitive issues could be at play.

- Acknowledge that the interview is difficult for the patient and for you.

- Consider “floating a hypothesis” about why the interaction may be challenging

- Be open to developing a trusting relationship

- Empathize

Reflection