The Illness Narrative and HPI

The history allows a physician to understand a patient’s illness and often, to diagnose their disease. For lay people, the two terms illness and disease may mean the same thing, but there’s a critical difference. Illness is a patient’s unique experience of being sick, influenced by biology, context, and culture. Disease can be defined as a disruption of normal biologic function at the cell, organ, or system level.

Most patients with a disease also have an illness – they somehow feel unwell – but some (like those with early diabetes) may not. Most patients with an illness also have a defined biologic disease – but some may not. And different people may be affected very differently by the same disease – their diagnosis is the same, but their illness is not.

Patient Voices: Illness Narratives

In this New York Times series, different patients with the same disease describe their unique experiences of illness, sharing the impact of disorders like Parkinson’s, ALS, or sickle cell anemia.

Here, we include stories of people living with bipolar disorder. The introduction says “Riding the ups and downs of bipolar disorder can cause havoc for those living with the disorder and their loved ones. Here are firsthand accounts of those living with bipolar disorder.”

Listen to at least two of these stories. How are they similar? How are they different? How would hearing them help you to care for the whole person? As you listen, think about:

- Who is this patient?

- How does this patient experience this illness?

- What are the patient’s ideas about the cause of the illness?

- What are the patient’s feelings about the illness?

- If applicable, what does the patient want from their healthcare now?

Eliciting the Illness Narrative

Eliciting a patient’s illness narrative accomplishes three things. First, hearing the story in a patient’s words can help make the diagnosis, painting a clearer picture of the presenting problem than a series of closed-ended questions. Second, the illness narrative provides context that helps with diagnosis or treatment. And third, simply telling one’s story can be therapeutic. Even as a first-year student, you can contribute to your patients’ healing simply by listening.

To elicit a patient’s narrative, begin with an open ended question or request about the chief concern. “Why don’t you start at the beginning and tell me all about ___” cues your patient to report everything they’ve noticed. Encourage them to continue the narrative with verbal or non-verbal facilitators, like mmm-hmms or nodding, another open-ended question or by reflecting the last few words that they said.

Example Illness Narrative

The patient’s perspective is an important – and often overlooked – element of the illness narrative. Attribution, your patient’s ideas about the reason for their symptoms, can be a clue to the correct diagnosis or give you insight into concerns and cultural context. The impact of the illness on your patient’s day-to-day life can be explored with questions like:

- How has this affected your life?

- What worries you most about (symptoms)?

- How are you coping with all of this?

- How has this affected your ability to do what you need to do?

- How has this impacted you emotionally?

Example Patient Perspective

History of Present Illness & Diagnostic Reasoning

When the illness narrative is complete, the physician shifts to a different style of inquiry, asking focused and closed ended questions to complete the history and help their diagnostic reasoning. These questions are intended to:

- elicit a complete description of symptoms

- clarify the time course

- differentiate between diseases on the differential that have different associated symptoms or risk factors

Diagnostic reasoning is the process of arriving at an explanation for a patient’s problem and communicating that to the patient. Although the illness narrative contributes to diagnostic reasoning, more history is usually needed. Patients don’t know what is important and what is not, so it’s up to the clinician to gather all relevant information. A complete and detailed history can help to differentiate among the many possible causes of a symptom and in studies of people with a new concern, the diagnosis is suggested by the history most of the time.

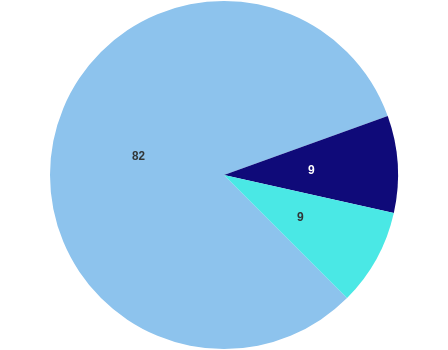

Diagnoses suggested by each part of patient encounter1,2

History

History  Physical exam

Physical exam  Labs and imaging

Labs and imaging

Completing the description of symptoms

Although there are over 10,000 known human diseases, patients present with fewer than 200 symptoms. A clear and detailed description of the presenting concern will help differentiate among the many possible causes.

Consider a patient presenting with abdominal pain – a complete description of the symptom can limit the possibilities substantially. Severe pain that came on suddenly would lead you to consider different diagnoses than mild, intermittent pain. The list of diseases that cause pain in the upper right abdomen is different from those that cause pain on the left. Each of these details can be diagnostically useful – and you can gather them even before learning about causes of this chief concern.

OPQRSTAAA: A mnemonic for defining symptoms

| OPQRSTAAA: A mnemonic for defining symptoms | |

|---|---|

| O nset | How did this start? What was the first thing you noticed? |

| P osition | Where in the body did you feel it? |

| Q uality | Tell me what the pain was like. Was it sharp, throbbing, dull? |

| R adiation | Did you feel it anywhere else in your body? |

| S everity | How bad was it? Were there things it kept you from doing? |

| T iming | Did it get better or worse? Come and go? |

| A ggravating factors | Is there anything that made it worse? |

| A lleviating factors | Is there anything that made it better? What did you try? |

| A ssociated symptoms | Was there anything else you noticed? |

Clarifying time course

The diseases that cause acute and chronic presentations of the same symptom are often different. In general, a symptom with a “sudden” onset came on over minutes; an acute symptom over hours to days; subacute over weeks to a few months; and a chronic symptom has been present for longer than several months.

Understanding the acuity of symptoms both helps with diagnosis and determines the urgency of the workup. A patient who has had similar headaches for years is unlikely to have a severe problem, but new onset headache could be something serious.

The temporal relationship between different symptoms and treatments can also be diagnostically useful. For example, patients with infectious gastroenteritis usually develop nausea or diarrhea first, before they have any abdominal pain. Those with surgical problems usually develop pain first. Be sure you understand which symptom came first and how others followed.

If the time course of your patient’s illness is unclear, clarify it by asking questions like:

- When did you last feel well?

- What was the first thing you noticed?

- What happened next?

- How have things changed since (start of symptoms)?

Communication techniques

Examples:

Transition to the past medical history

Once you have a complete picture, summarize one more time and check to see if there is anything else that your patient would like to add. Then transition explicitly to the next stage of the interview, with a signpost like “Next I’d like to ask about other health problems you may have.”

Reference & resources

Street RL, Makoul G et al (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 74(3):295-301 LINK

Patient Voices – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Peterson, MC, Holbrook, JH, Von Hales, D, Smith, NL, Staker, LV. Contributions of the history, physical examination, and laboratory investigation in making medical diagnoses. West J Med. 1992;156:163–165.

Hampton, JR, Harrison, JM, Mitchell, JR, Prichard, JS, Seymour, C. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. Br Med J. 1975;2:486–489