Negotiating a Patient-centered Plan

In clerkships, you’ll be asked to propose a plan for testing, treatment, education, and follow-up. This chapter and the clinical skills workshop cover important context and communication skills for negotiating a patient-centered plan.

- Sharing information effectively

- Promoting medication adherence

- Confirming patient understanding by eliciting questions and using teach-back

- Understanding patients’ preferences, goals, and values

- Creating a plan for behavior change

When there is more than one reasonable approach to a problem, physicians and patients should share decision making The clinician discusses treatment options with the patient, providing them with enough information to help them make an informed choice. This patient centered approach integrates the clinician’s expertise with a patient’s preferences, lifestyle and goals to co-create a treatment plan.

![]()

In an emergency, in the hospital, or when there is only one reasonable option, physicians may lean more towards the ‘traditional’ approach: making a recommendation, explaining it, and inviting questions or additional input. A clinician may also use the more traditional approach because they understand their patient’s preferences based on a long relationship. However, many practicing physicians trained before shared decision making was widely used, and organizations like the American College of Cardiology have developed continuing medical education resources to help clinicians shift to more collaborative decision making. You’ll see an example later in this chapter.

Key communication skills in negotiating a plan.

Sharing information

Clear communication is critical when discussing a plan. Modern health care is complex, and many people have low health literacy (LHL) meaning that they struggle to obtain, process and understand basic health information. LHL is associated with higher rates of hospitalization and emergency care, lower use of preventive services like flu shots and mammography, and less accurate use of prescribed medication. Elderly people with LHL have poorer health status and higher overall mortality.

Experts recommend a ‘universal precautions’ approach to sharing health information with all patients. Although some demographic groups are disproportionately affected by low health literacy, people who are highly educated in other fields may struggle with health-related information, and the stress of illness can interfere with cognitive processing. Use these strategies to communicate as clearly as you can about the plan.

- Use plain language

- Speak clearly and at a moderate pace

- Limit information to 3-5 key points

- Present the most important information first

- Break information into understandable ‘chunks’ and check understanding after each.

Plain language is clear and straightforward and avoids medical jargon. Whenever possible, complicated terms are replaced with simpler ones. This plain language dictionary from the University of Michigan lists complicated terms along with suggested alternatives.

Give your patients written instructions to take home as a reference. Illustrations and infographics can increase understanding – you can sketch something in the moment or keep track of reliable and clear websites & apps for problems common in your patient population. Vetted patient education resources are available via the many EHRs and on the Health Sciences Library Care Provider Toolkit – look in the right hand column.

Although you should use ‘universal precautions’ at every visit, you should also pay attention to clues that your patient may need more support from your team. Incomplete forms, frequent missed appointments, difficulty with listing medications, and identifying medications by opening the bottle rather than reading labels are all clues to low health literacy.

Optimizing adherence with medication counseling

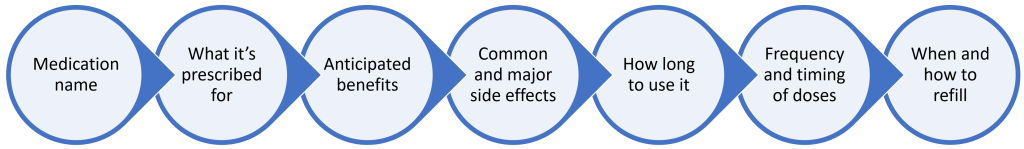

Studies have shown that adherence to a treatment plan is better when patients are included in decisions about their care. Once those decisions have been made, counseling about a new prescription should include:

Another way to improve adherence is to proactively address the 3 most common reasons for nonadherence – the 3 Cs:

- Cost. Research the cost of the drugs you’re considering – a clinic or insurance formulary and Good Rx.com are helpful sources. Several large pharmacy chains, including Walgreens, Target and Walmart offer a list of generic medications for $4 per month. If you’re considering a high cost drug, a pharmacist can determine whether the patient’s insurance will cover it and what the co-pay will be.

- Complexity. Studies show that adherence decreases as the frequency of dosing increases. Choose once a day drugs when possible, ideally given at the same time as any meds your patient is already taking. Combination pills containing two medications for the same condition can decrease the complexity of your patient’s drug regimen, although the cost of combination pills may be higher than separate pills.

- Concerns about the balance of risks and benefits. For many chronic conditions like hypertension and hyperlipidemia, medications won’t make your patient feel any better but they may experience side effects. Clearly describe the benefits your patient can expect from taking the medication, get their buy in, and check in on any side effects at follow-up visits.

Confirming your patient’s understanding.

People are often reluctant to ask their doctors questions, and studies show that patients with lower health literacy ask even fewer questions. Even if the plan seems very straightforward, ask ‘What questions do you have?’ to normalize that most people will.

Then use teach back to confirm your patient’s understanding. Think of teach back as a test of how well you did in sharing information. Ask a question like ‘So I can be sure that I explained things well, can you tell me what I told you about your treatment?’ If your patient isn’t able to repeat the key points accurately, assume that you have not communicated clearly and re-explain the most important information.

Preference sensitive decisions

In many clinical situations, there are two or more reasonable approaches to care, each with its own risks and benefits. Because different patients place different value on these tradeoffs, these decisions are considered preference sensitive and should be made after patients have enough information to make an informed choice.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality SHARE approach is a communication map for shared decision making, a collaborative conversation that integrates a clinician’s expertise with a patient’s values and preferences to choose the option that fits best for that individual.

S eek your patient’s participation: Explain to the patient that there are two or more medical options, inviting them to take part in making a choice. A patient’s preference to not participate or to delegate decision making to someone else should be honored.

H elp your patient explore and compare treatment options: Discuss the benefits and potential harms of each option using the ‘universal precautions’ strategies outlined above. Decision or conversation aids (discussed below) may also be helpful.

A ssess your patient’s values and preferences: Establish an open dialogue to clarify the patient’s personal values and how they impact their preferences for care.

R each a decision with your patient: Mutually agree on the best option and discuss next steps. Keep in mind and acknowledge to the patient that it may take more than one visit to reach a decision.

E valuate your patient’s decision at follow-up. Involve your patient in making a follow-up plan and proactively reaching out if any concerns arise.

Decision & conversation aids

A decision aid is a standardized, evidence-based tools designed to facilitate shared decision-making. A 2017 Cochrane review found that decision aids increase patient participation in shared decision making, improve their knowledge of their options, and positively impact clinician-patient communication.

Good decision aids use plain language and are tested with members of the target audience. They typically include:

-

- Up to date information about the medical condition

- Risks and benefits of the treatment alternatives

- Clarification to help patients understand their values and preferences

The American College of Cardiology has developed training videos and decision aids for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation and other common cardiac problems. Watch this 2-minute video of a cardiologist talking with a patient using a decision aid, then review the decision aid itself.

Planning for behavior change

The first step in counseling for change is assessing your patient’s readiness. For pre-contemplative patients, who are not yet considering change, you may ask permission to share a bit of information and re-visit the topic later on. For contemplative patients, who are considering but not committed to change, you can use motivational interviewing to increase their readiness and your plan might be to offer resources or another visit.

In the preparation stage, patients are actively planning to make a change. They are clear in their motivation but may not know how to make it happen. Open ended questions help clarify what information they need, what barriers need to be overcome, and what resources can be enlisted. The goal in the preparation stage is to support the patient in developing a specific and realistic plan that honors their individual ideas and situation.

First, explore options, starting with any ideas the patient may have. For example, for a patient who has indicated they’d like to increase exercise you might ask questions like “What are some ideas you’ve had for adding exercise into your busy life?” “Have there been times in your life when you’ve been able to exercise more? What worked then?”

If the patient has a specific idea that feels like it would work, continue down that path. If not, with the patient’s permission, offer a menu of options that may be effective. “We have some programs here at the clinic for patients who’d like to increase their movement, would you like me to tell you about them?” After sharing the information, ask if one of the options seems like it would work for your patient.

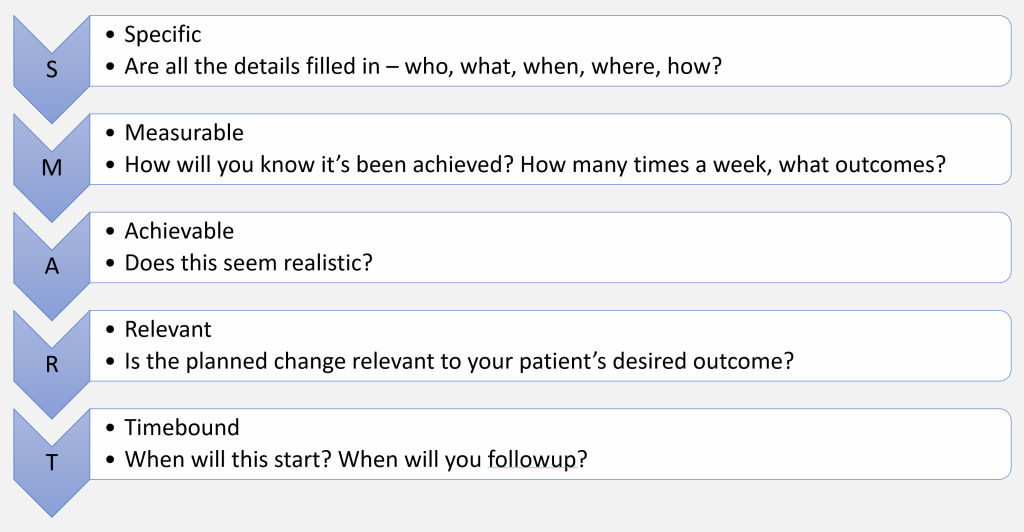

Then develop a specific plan for the option chosen. A more detailed plan is more likely to succeed – you can use the SMART framework below.

Anticipate and troubleshoot potential barriers “What might get in the way of that plan? What could you do if that happens?” “Is there something or someone who could help make this easier?”

And make a plan for follow-up.

Treatment plans for multiple chronic conditions

Treatment plans are more complicated when patients have multiple chronic conditions. The burden of medications and healthcare visits increases with each additional chronic illness, as does the risk of drug-drug interactions and adverse effects. One third of adults over 60 take five or more medications.

Evidence based guidelines for one disease may or may not be applicable to people with multiple diseases; guidelines are often based on studies that limited participation to people without other major health problems. As you use a guideline in the clinic, pay attention to the population the it applies to.

As you propose adding a new medication to an already long medication list:

- Perform a comprehensive medication review. Is there anything that it would be appropriate to de-prescribe?

- Beware of increasing complexity. Ensure the new medication can be taken at the same time as others.

- Check for drug-drug interactions. If you are entering a new prescription via the EHR, pay attention to any electronic alerts about interactions. You can also check for interactions with different apps. Please refer to the HS library Mobile Resources page to access the following resources and apps along with many others. Consider exploring these on-line resources/apps so you are prepared to use them when caring for patients on clerkships.

- ePocrates: Free version available that allows you to search medications individually to learn about dosing in adults and pediatrics, side effects, monitoring, interaction characteristics etc. You can also use their drug “interaction check” feature found under “tools” in the menu. Need to sign up to use on-line or app version. Very helpful to have this resource when on clerkships.

- DynaMedex. On line option: Go to menu (3 bars in left upper corner.) Click on drug interactions which takes you to an AI page (Micromedex Assistant). Click on menu (4 bars in left upper corner) and chose drug interaction search. You can add as many drugs as needed to the search. You can also download the app.

Deprescribing

De-prescribing is the planned process of stopping or reducing medications that may no longer be of benefit or may be causing harm. The healthcare system is geared towards adding new medications rather than stopping them, and medications like proton pump inhibitors, antipsychotics, and diabetes medications are often continued even when the benefits no longer outweigh potential harms. There is growing research and new resources to support careful de-prescribing in some situations. A detailed ‘how to’ is beyond the scope of this workshop, but excellent resources are listed at the end of this chapter.

When opinions differ

At times, you and your patient will not see eye to eye on the next best steps in their care. This can feel particularly challenging if you worry their preferred path will lead to a worse outcome. The following steps may help you reach common ground. It may also help to involve others that the patient trusts in the conversation. At the end of the day, however, remember that the choice is theirs.

Engaging in Negotiation: Reaching common ground in decision making

| Step 1 | Explore the patient’s perspective | Ask open-ended questions about the patient’s understanding and concerns about the illness and its treatment. |

| Step 2 | Explain your perspective | Use terms that are understandable and familiar. Share what you hope will be beneficial for them if they follow your recommendations. |

| Step 3 | Acknowledge the difference in opinion | Use non-judgmental language. Accept difference. |

| Step 4 | Create a common ground | May need to offer a compromise or ask what the patient is willing to do. |

| Step 5 | Settle on a mutually acceptable plan | Once the plan is developed check in to make sure it is acceptable. Use the “teach-back” method. |

Treatment plans & conflicts of interest

Conflicts of interest have the potential to influence decisions about testing and treatment. Patients’ best interests sometimes conflict with a physician’s self-interest or the interests of hospitals, insurers, and industry partners. From an ethical standpoint, patients’ interests must always come first. Conflicts of interest can impact trust in an individual physician and in the profession as a whole.

Conflict of interest can be defined as a set of circumstances that creates the risk that professional judgment or action will be affected by a secondary interest like the ones above. A classic example of physician behavior affected by a secondary interest is pharmaceutical marketing. Even small gifts, like a free lunch or a branded pen, have been shown to increase prescribing of the specific drug being marketed. Because of this, many academic medical centers (including UW Medicine) have restricted pharmaceutical representatives from visiting or providing meals or gifts. This practice remains more common in post-graduate practice, and clinicians should be aware that it can lead to changes in prescribing that increase cost and impact patients.

Other financial relationships with industry, like research funding for drug or device development, also create conflicts of interest. These relationships may be positive for everyone involved, including the public who will benefit from a life-saving innovation. However, the COI must be disclosed in publications and presentations so that the audience can critically evaluate the message in light of the potential conflict. Because this information is generally not known to individual patients, it is critical for clinicians to stay mindful of how their conflicts of interest might impact treatment decisions.

Practice based financial incentives can also influence physician behavior. Quality measures that reward physicians or practices when a certain percent of their patients achieve a screening or treatment target could lead to avoidance of sicker patients less likely to achieve that target. In a private practice environment, more referrals for diagnostic tests or procedures could influence income.

Key points

- Shared decision making aligns the treatment plan with patients’ values and lifestyle and improves adherence to the chosen course of treatment.

- The ‘universal precautions’ approach for health literacy improves information-sharing. Use plain language, start with the most important information and limit the total amount.

- Teach back is an effective tool for ensuring understanding.

- Decision aids are available for many preference-sensitive decisions and are becoming more common in clinical practice.

- Review the medication list whenever a new medication is added.

Additional References & Reading

Prevalence of Multiple Chronic Conditions Among US Adults, 2018. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020

Deprescribing is an Essential Part of Good Prescribing. American Family Physician 2019

- CDC’s Provider Resources for Talking to Parents About Vaccines

- Immunization Action Coalition Responding to Parents

- This video from Dr. Nancy Messonier, the director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization