Sim 3. Testing diagnostic hypotheses

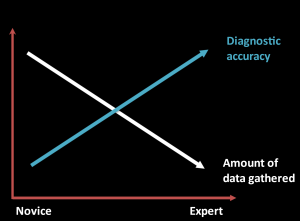

Although expert clinicians gather much less data than novices, their diagnoses are more likely to be accurate. While novices rely on a comprehensive H&P to uncover important details, experts can target questions and exam to the situation, adapting the information they choose to gather to what they have already learned.

Experts gather less data but their knowledge and experience allows them to target better data than novices. Comparing illness scripts can help you identify the signs and symptoms most helpful in differentiating between diagnoses.

Compare the three causes of acute pharyngitis below. Some features, like acute onset and fever, are common to all three, but there are also important differences. Most patients with a viral URI have cough or rhinorrhea while those with streptococcal pharyngitis do not. Exposure to children makes streptococcal pharyngitis more likely in adults. And cervical lymphadenopathy is common in strep pharyngitis and mono but uncommon in routine viral URI.

| Sore throat & fever | History | Epidemiology & risk factors | Physical exam |

| GAS pharyngitis | Fever

No cough or rhinorrhea |

Common cause of pharyngitis: 30% of kids and 15% of adults

Most common in 3-14 y.o. In adults: Exposure to kids |

Pharyngeal erythema

Tonsillar exudate Tender cervical adenopathy May have palatal petechiae |

| Mono (EBV) | Malaise, headache, fever, anorexia

Significant fatigue |

Peak incidence: 15 to 24

<2% of adult pharyngitis |

Tender cervical adenopathy

May have splenomegaly, diffuse lymphadenopathy, palatal petechiae |

| Viral URI | Usually cough or rhinorrhea

Fever less common |

Common cause in kids and adults | Pharyngeal erythema, nasal discharge

No adenopathy |

A novice would learn about the absence of cough, exposure to children and the presence of cervical adenopathy during a complete H&P. Experts would target their focused questions to uncover these differences, which are diagnostically useful in sore throat, and add that information to their problem representation.

Sometimes, a specific symptom or risk factor is required to make a diagnosis. For example, if a patient with fever has never travelled outside the Washington, they cannot have malaria. Focused question can also target red flags that require additional investigation, like severe pain with jaw opening in a patient with sore throat (truisms).

Quantifying diagnostic utility of clinical findings

Symptoms and physical exam signs can be considered diagnostic tests, just like labs or imaging. Their validity (or accuracy) refers to their ability to distinguish between people who have a disease and people who do not.

Just as with lab testing, not all positive results are true positives. Some patients with crushing substernal chest pain have a diagnosis other than acute coronary syndrome. A yes or no answer to a focused question usually doesn’t ‘rule in’ or ‘rule out’ a disease, it just changes the probability. Same with physical exam.

The validity of symptoms in diagnosing some diseases has been studied. The JAMA Rational Clinical Exam series and “The Patient History: An Evidence-Based Approach to Differential Diagnosis” summarize much of the available data. As your clinical experience grows, you’ll also get a sense of how much certain symptoms change the probability of disease in the patient population that you serve.

Likelihood ratios

The diagnostic utility of a clinical feature is often reported as a likelihood ratio (LR). As you learned in Research Methods/FMR, LRs are used to convert the pre-test probability into the post-test probability based on the results of “test” (in this case a symptom, risk factor or exam finding)

Tests with LRs greater than 1 increase the probability of disease – the higher the LR, the more strongly the finding supports it. Tests with LRs less than 1 decrease the probability of disease – the closer the LR is to zero, the more strongly the finding argues against it. Likelihood ratios between 0.5 and 2 change the probability of disease minimally and a LR of 1 means a question or maneuver test is not worth the time – the probability of disease does not change either way.

With a LR and an estimate of pre-test probability in hand, you can estimate the post-test probability with the nomogram you saw in FMR. A more qualitative approach that may work better in the clinic is to remember the focused and differentiating questions most helpful for different clinical problems.

Here’s an example, from a JAMA Rational Clinical Exam article on lumbar spinal stenosis, a common cause of back pain in older adults.

| LR+ (95% CI) | LR- (95% CI) | |

| Symptoms | ||

| Absence of pain when seated | 7.4 (1.9-30) | 0.57 (0.43-0.76) |

| Improvement of symptoms when bending forward | 6.4 (4.1-9.9) | 0.52 (0.46-0.60) |

| Bilateral buttock or leg pain | 6.3 (3.1-13) | 0.54 (0.43-0.68) |

| Neurogenic claudication | 3.7 (2.9-4.8) | 0.23 (0.17-0.31) |

The authors identified three symptoms that strongly support spinal stenosis if the patient has them: the absence of pain when seated, improvement in symptoms when bending forward, and bilateral buttock or leg pain. The positive LRs for all three of these symptoms is > 5. The absence of these symptoms, however, argues only weakly against spinal stenosis because the negative likelihood ratios are between 0.5-1.

Neurogenic claudication – leg pain that develops with standing or walking – supports a diagnosis of spinal stenosis less strongly (the LR is lower). But with a negative LR of 0.2, the absence of neurogenic claudication argues more strongly against spinal stenosis.

Hypothesis-driven physical exam

Having diagnostic hypotheses in mind can focus your attention on the most helpful exam maneuvers and findings. You are much more likely to notice a soft heart murmur if you’re thinking about pulmonary hypertension than if you are just going through a ‘complete’ PE. Your diagnostic hypothesis can also add specific maneuvers to your exam, those with findings that change the probability of the diagnoses on your differential.

Like symptoms, the presence or absence of hysical exam findings can move the probability of a diagnosis up or down. That might be enough to forego a lab or imaging study because the likelihood of a diagnosis is now so low – or to justify expensive testing because the likelihood is now higher. In the sim workshop, we’ll discuss some exam findings that are helpful in patients with chest pain.

Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis, available full text through the Health Sciences Library, is an excellent summary of the evidence supporting physical exam. For some exam maneuvers, there isn’t any evidence because it has never been formally studied. Sometimes the evidence is just what you’d expect, and sometimes the evidence is surprising.

Knowledge Check

Resources & references

The Patient History: An Evidence Based Approach to Differential Diagnosis. Henderson, Mark et al. Lange, 2012. LINK

Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis, 5th ed. McGee, Steven R. Elsevier, 2022. LINK

JAMA Rational Clinical Exam Series LINK