Sexual history

Sexual health is an integral part of physical and emotional health, and the sexual history enables clinicians to understand their patients’ identities, address sexual health concerns, and assess the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Surveys show that most adults want their physicians to ask about sexual health and that most are comfortable reporting their sexual orientation and gender identity. However, clinician discomfort is a common barrier to eliciting this important information. The more often you take a sexual history, the more comfortably you will become – this chapter provides a framework for practice.

You will learn about health disparities related to gender and sexual orientation in the Themes course; about STIs and their clinical manifestations in the Infections & Immunity block; and about sexual and reproductive function and concerns in the Lifecycle block. By the time you enter clerkships, you should be able to:

- Recognize the impact of sexual health on overall health

- Demonstrate the use of inclusive and affirming language in performing a sexual history

- Outline the elements of a comprehensive sexual history

- Adapt the sexual history to the clinical situation

Because this may be a sensitive area, it’s important to set the stage well. You will have already confirmed gender at the start of the visit, by reviewing an intake form, asking how your patient would like to be addressed, or asking their pronouns. Because rapport is as important as the questions that you ask, many clinicians take the sexual history after the social history – it may come up naturally as you discuss relationships and support.

As you transition to the sexual history, establish the medical relevance of these questions, connecting the reason you’re asking to your patient’s overall health or presenting concern. You should also confirm permission, recognizing that a sexual history may be triggering for those with a history of trauma. If someone does not wish to provide a sexual history, respect their autonomy and gently revisit the topic at the next visit.

Sample transition statements:

I’d now like to ask some questions about your sexual history to make sure I recommend the best preventive care for you. Is that OK?

I’m working on my skills in asking about sexual health and practices because these are important to overall health. May I ask you some confidential questions? If you’d prefer not to answer any specific questions, you can just say, ‘pass’.

Inclusive language

To avoid making any assumptions about your patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, always begin with open ended questions and use gender neutral language. Refer to ‘partner’ or ‘spouse’ and avoid referring to partners by gendered pronouns unless the patient has done so first – it’s ok to mirror language that your patient uses.

If you slip, apologize. Example: you make an assumption about a partner’s gender and realize it as the pronoun leaves your mouth. Say ‘I’m so sorry, I realize I made an assumption there. What are your partner’s pronouns?”

In the clinic, review any intake forms that the patient has completed before starting the history.

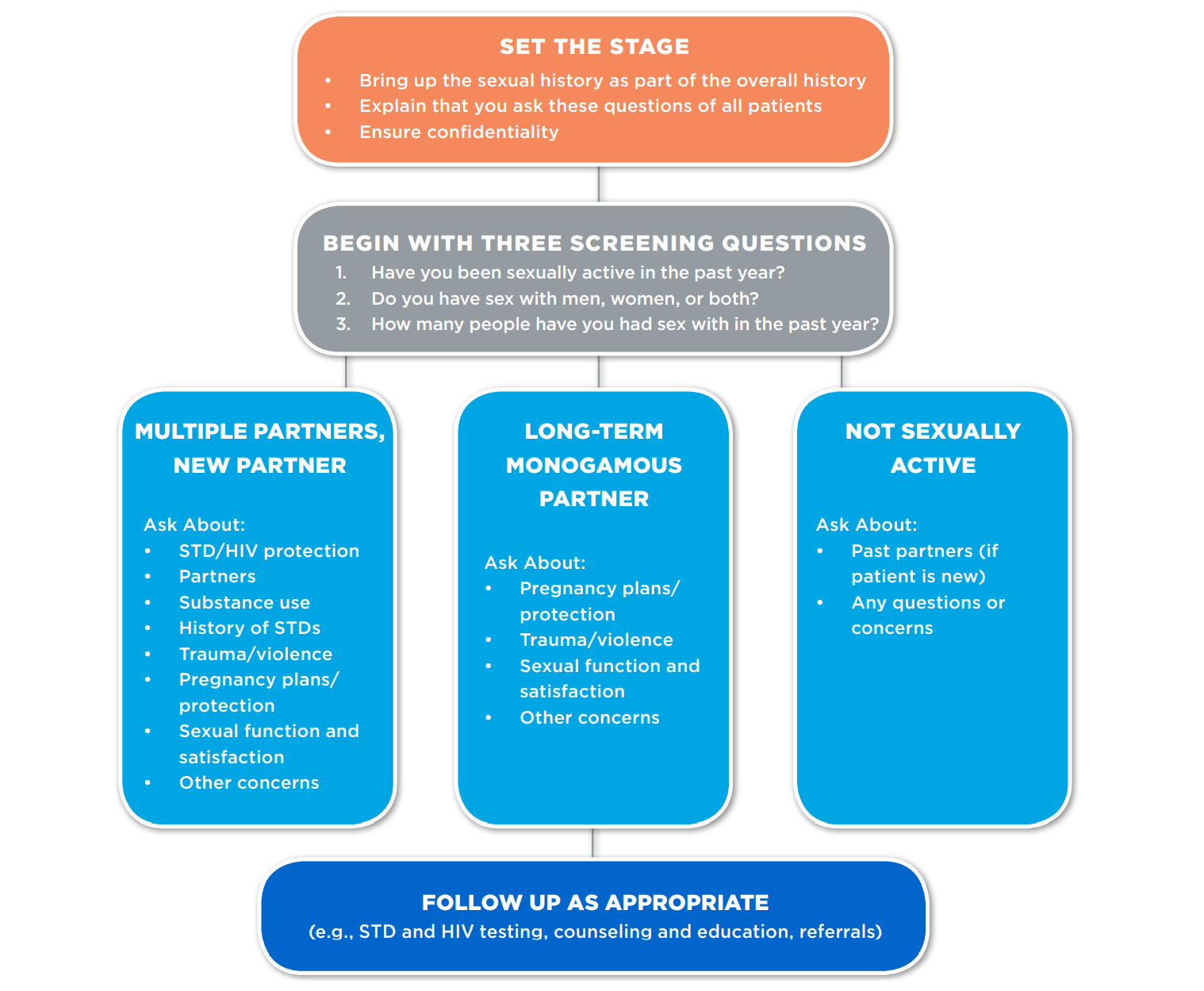

Gathering information: Three screening questions

Start with three questions:

- Have you been sexually active in the past year?

- How many people have you had sex with in the past year?

- What are the genders of your partners? This is an alternative to the commonly used question ‘do you have sex with men, women, or both’ (included in the graphic below) that acknowledges the range of gender identities.

For people with multiple partners, a new partner, or a partner who is not monogamous, a more detailed history is done to assess the risk of STI. For those at higher risk, patient counseling decreases the likelihood of sex without a condom and decreases the acquisition of STIs. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is 99% effective when taken daily and decreases new HIV infections by up to 75% under ‘real world’ conditions.

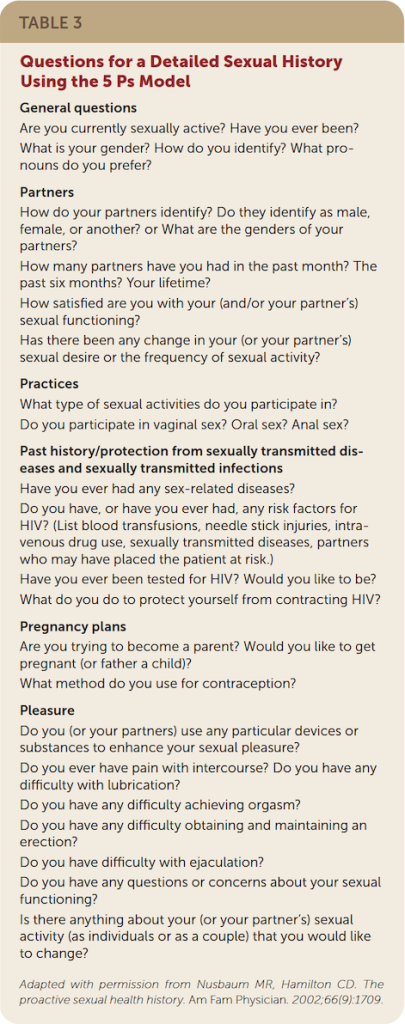

A commonly used communication map for the sexual history is the 5Ps which was developed by the CDC with STIs in mind. The first P (partners) was covered by the three questions above. Some clinicians add a 6th P for ‘pleasure’, to remind themselves to ask about sexual function and satisfaction.

| Partners | Goal: Assess the risk of sexually transmitted infection (STI) and guides further questions and counseling. |

| Practices | Goal: Guide STI risk counseling and anatomic sites for STI testing if needed. |

| Protection | Goal: Ensure those at risk for STI are using effective means of preventing STI transmission. |

| Past STIs | Goal: Help with STI risk assessment, and may identify people who have been undertreated in the past. |

| Pregnancy | Goal: Ensure those who do not desire pregnancy are using contraception appropriate to their situation. Can also open the door to a discussion of fertility, family planning and options for building a family for all people. |

Findings phrases and questions that work for you:

Use a calm and professional tone, but don’t be so concerned about asking questions in the ‘right’ way that you become inauthentic or robotic. To maximize comfort, a sexual history should feel more natural than scripted, but you should try out phrases and questions that feel authentic to you.

Here are three recent references that offer suggestions:

- (To the right) Questions for a Detailed Sexual History Using the 5 Ps Model from the American Family Physicians article Sexual Health History: Techniques and Tips

- Pages 8-11 (Sexual Risk Assessment) of the Sexual History Toolkit from National LGBT Health Education Center and the National Association of Community Health Centers

- (Below) Suggestions for taking an inclusive history from eQuality Toolkit, Part 1: Inclusive Communication Skills

| Question/ Statement | Rationale for All Patients |

| “How would you like me to address you?” | When providers ask this question first to all new patients, they avoid mis-identifying or misgendering patients whose legal name differs from the name they actually use. New patients can be misgendered when honorific titles (Ms., Mr., etc.) are used in an introduction. Asking for a patient’s “real name” can also be unclear and/or demeaning. The phrasing provided here allows the patient to interpret the question and designate what name and/or title to use. In emergency settings, this is appropriate until a full inclusive history can be taken. |

| “I ask these questions to all of my new patients so that I can give you the best care possible.” | Approaching these topics with patients may seem difficult because they are not always included in medical histories. Introducing identity questions this way may help explain this process to those individuals who have not yet discussed these issues with providers. |

| “What was your sex assigned at birth?” | Understanding male/female sex assigned at birth (MSAAB/FSAAB) or intersex/DSD is crucial to understand the starting point of any sex-specific care that the patient will need (See Part Ill). |

| “What is your gender identity?” | This allows the provider to understand whether the patient’s gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth-e.g., whether the patient identifies as cisgender (match) or transgender, on a spectrum, genderqueer, nonbinary, etc |

| “Do you have sex with men, women, both, or anyone else?” | “Men, women, or both” is a common phrase providers use, but this excludes identities outside of the gender binary-so providers should use the more inclusive wording here or in the next example. |

| “Can you tell me more about the gender identities of your sex partners?” | This is an open-ended version of the question directly above, with the intent to have the patient disclose rather than offering genders/identities of the patient’s partners. This breaks down a cisnormative assumption that gender identity (man/woman) also reveals sex assigned at birth (male/female), and differences can be important when considering preventive care. |

| “Can you tell me more about the types of sex you are having?” | This question allows the patient to describe the type(s) of sex they engage in. The provider should follow up with specific questions to clarify and fully understand each patient’s behaviors and thus risk factors (see next question). |

| “What parts do you use when you and your partner(s) have sex?” | All patients are capable of having oral and anal receptive intercourse and may therefore need related care/counseling. The only way to know for sure what risks a patient has is to ask about specific behaviors and body parts. |

| “If your sexual activities change, you may need additional screenings.” | People change, and behaviors that the patient does not report during one visit may be relevant in the future. This is true of all patients. |

| “What is your relationship to the patient?” | When a family member accompanies the patient, this open-ended question replaces questions such as “Are you the patient’s husband/wife?” which make assumptions about the patient’s relationship status and sexual orientation. |

Knowledge Check

Additional Resources

- Sexual Health History: Techniques and Tips. From American Family Physician, 2020. For the purposes of this SP interview, you can stop at “Opportunities for Prevention.”

- Taking a Transgender Inclusive Sexual Health History, on Bedsider Provider

- eQuality Toolkit, 2019. Part 1 on Inclusive Communication Skills is a very useful resource.