31 Design Inspiration: Pandoras and Paper Dolls

Pandoras

During the eighteenth century, fashion dolls, also known as poupée de mode, Pandoras, and Queen Anne Dolls, were sent all over Europe in order to disseminate the latest fashions, most often from Paris, considered the fashion capital of the world thanks, in no small part to Marie Antoinette’s relationship with Rose Bertin, Paris’ premiere merchandes de modes and first celebrity fashion designer. Although fashion dolls had existed prior to the eighteenth century, the growing importance of fashion as a sign of one’s cultural (and political) cache contributed to the enhanced presence of the dolls. At a time when more and more people had access to consumer goods from all classes, the aristocracy in particular were anxious to demonstrate their superiority via outward signs such as wardrobe. The dolls were so important that they were even given diplomatic immunity, exempted from trade embargoes and granted safe passage during war.

Two dolls were generally sent out, la grand Pandora in court dress and la petite Pandora in everyday dress. The dolls were outfitted with complete wardrobes including undergarments and showcased the latest fashions as well as hairstyles and accessories. Rose Bertin had a life-size doll modeled on Marie Antoinette in her Paris shop window further cementing in the public’s mind the Queen’s position as the foremost fashion icon of the age. Hairdressers as well used dolls. The wars of the French Republic and Napoleon put an end to the safe passage of the dolls and contributed to the decline in their use, as did the rise of fashion magazines such as Galerie des Modes.

Fig. 1 and 2.

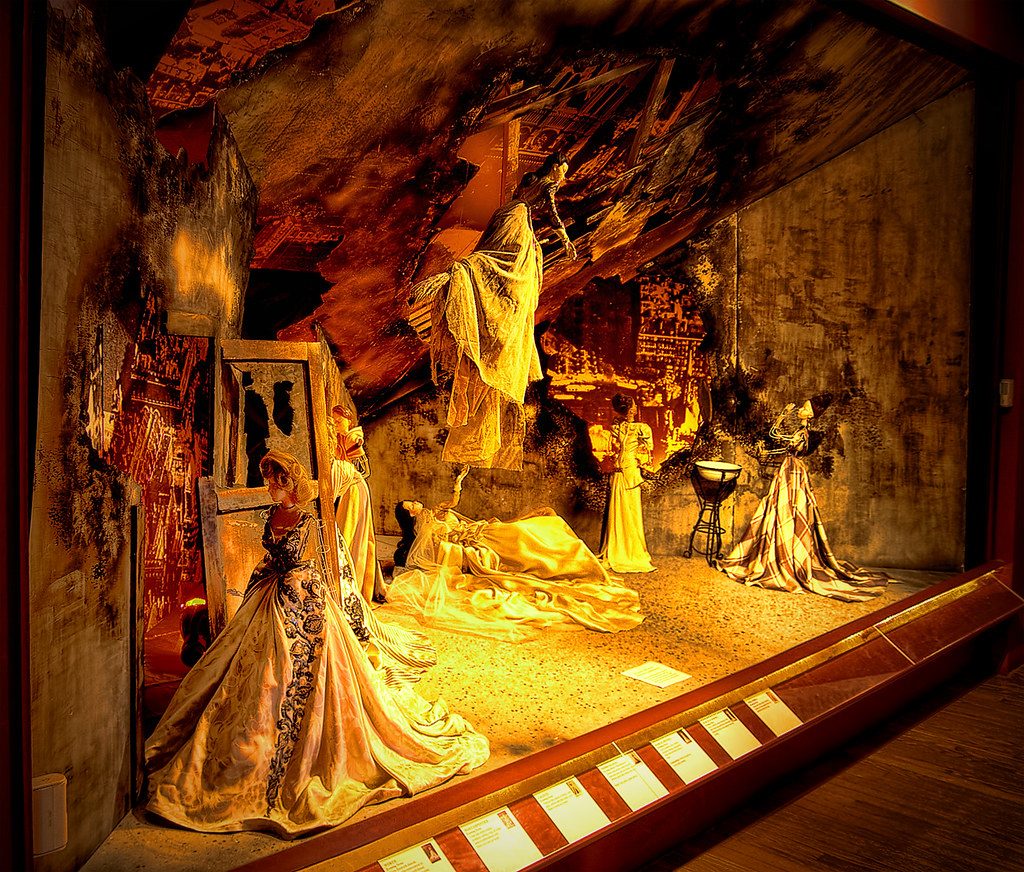

Théâtre de la Mode

After World War II, Nico Ricci, son of couturier Nina Ricci, hit upon the idea of using mannequins dressed by the great fashion houses to raise funds for war survivors and to revive the French fashion industry. Because materials were scarce, he proposed using dolls 1/3 the size of human beings. The dolls toured both Europe and the United States. The Théâtre de la Mode (Theatre of Fashion) consisted of 237 dolls and 15 sets created by artists such as Jean Cocteau, André Beaurepaire, and Christian Bérard. Some 60 fashion houses, among them Balenciaga, Hermès, Schiaparelli, Bruyère, Mad Carpentier, and Paquin participated in the exhibit. The Maryhill Museum of Art in Washington state acquired the mannequins although the original sets were lost.

At its point of departure, the Théâtre de la Mode derived from a well-established custom, dating, some say, from the Middle Ages, when traveling dolls were dispatched far and wide, their mission to present the elegance and prestige of Paris fashion to foreign courts…. The use of traveling dolls and their purpose of revealing the latest fashions became an exclusively Parisian tradition. To give new life to an old idea [emphasis added] during a period of crisis was all to the credit of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture [the League of Dressmakers] Parisienne…. But the real instigators of the project, its two dynamos, were Paul Caldaguès, a fashion journalist of exceptional talent and Robert Ricci. [1]

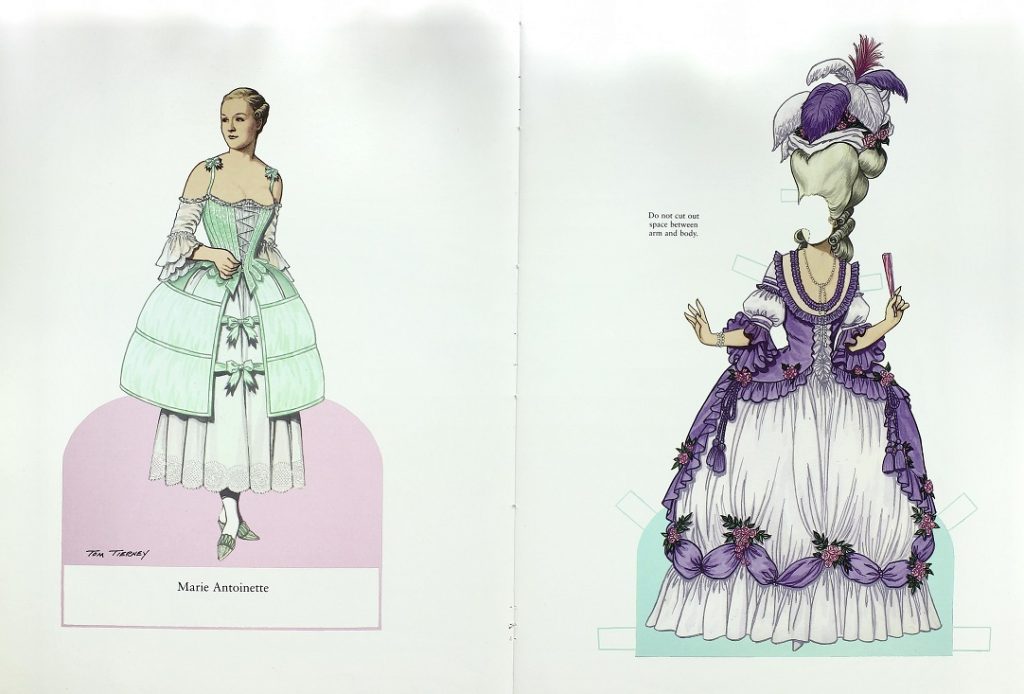

Paper Dolls

Paper dolls with costumes have existed since the mid-1700s in Vienna, Berlin, London, and Paris. They were hand-painted and created for wealthy adults and may have been used by dressmakers to advertise their wares. European manufacturers of the late 19th century began producing paper dolls of famous theatre personalities and royalty. In the 20th century, Dover Publicans began publishing books of paper dolls by Tom Tierney based on celebrities and historical figures including Marie Antoinette.

Bibliography of Sources:

Blanco, F., Jose, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee. Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe, volume 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2016.

Charles-Roux, Edmonde, Susan Train, and Eugene Clarence Braun-Munk. Theatre de la Mode. New York: Rizzoli, 1991.

Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Holmes, Pamela. “Fashion Doll with Accessories 1775-1760.” Fashion in the Age of Atlantic Revolution. March 11, 2014. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://history132atlanticfashion.wordpress.com/tag/pandora/.

St. George, Eleanor. The Dolls of Yesterday. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948.

Von Boehn, Max. Dolls and Puppets. Translated by Josephine Nicoll. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, Inc, 1966.

Weber, Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006.

Image Citations:

Fig. 1. Doll with dress and accessories. 1755-1760. English, wood and silk. Accession number: T.90 to V-1980. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London. From the Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed May 20, 2019. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O100708/doll-with-dress-unknown/.

Fig. 2. Doll’s dress. 18th century. Silk taffeta. The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. From the Museum of Fine Arts. Accessed May 20, 2019. https://www.mfa.org/exhibitions/think-pink.

Fig. 3. Mad Carpentier, Black and silver paisley pattern silk brocade evening coat. n.d., silk brocade. From: Edmonde Charles-Roux et al. Theatre de la Mode. New York: Rizzoli, 1991. Image 193.

Fig. 4. Jean Cocteau, Tribute to René Clair: I Married a Witch [reproduction]. 1945. Maryhill Museum, Goldendale, Washington. Available from: Flickr Commons. Accessed May 20, 2019. https://www.flickr.com/photos/glenbledsoe/4939364812/sizes/l/in/photostream/.

Fig. 5. Tom Tierney, Marie Antoinette. 2001. Color illustration. From: Marie Antoinette Paper Dolls. Toronto, Ontario: Dover Publications, 2001. Plates 2 and 3.

Footnotes:

- Edmonde Charles-Roux, Susan Train, and Eugene Clarence Braun-Munk. Theatre de la Mode (New York: Rizzoli, 1991), 32, 35. ↵

Feedback/Errata