The Social History

“It is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has.” – Sir William Osler

It is vital to understand the patients with whom we partner. Each lives in a greater social and community context outside of healthcare and their “life story” – the social history – is a critical part of their care. It allows us both to build rapport and to understand the challenges our patients face and the strengths they bring to their experience of illness.

The social history can cover many different areas, and in primary care, it’s often built over a series of visits rather than in a single interview. Like most aspects of the history, it should be tailored to the needs and issues of your individual patient, first focusing on the elements most important to their care. The “Social E” approach to the social history also encourages clinicians to detect and consider biological, chemical, physical, and psychological factors in the environment as well as other environmental change that could be affecting their patient’s health. It is an important part of the planetary health history.

Eliciting the Social History

Start with a transition to orient your patient to the change in focus, like “Now I’d like to ask you some questions about your life,” followed by an open-ended question. At their first visit with a patient, most primary care physicians will try to learn about each of the topics below. Some information about social context and stressors may already have been shared in the HPI. The clinician will explore other areas either by asking questions or by reviewing a form that the patient has completed before the visit.

Example of questions to ask:

Social and Environmental Factors & Health

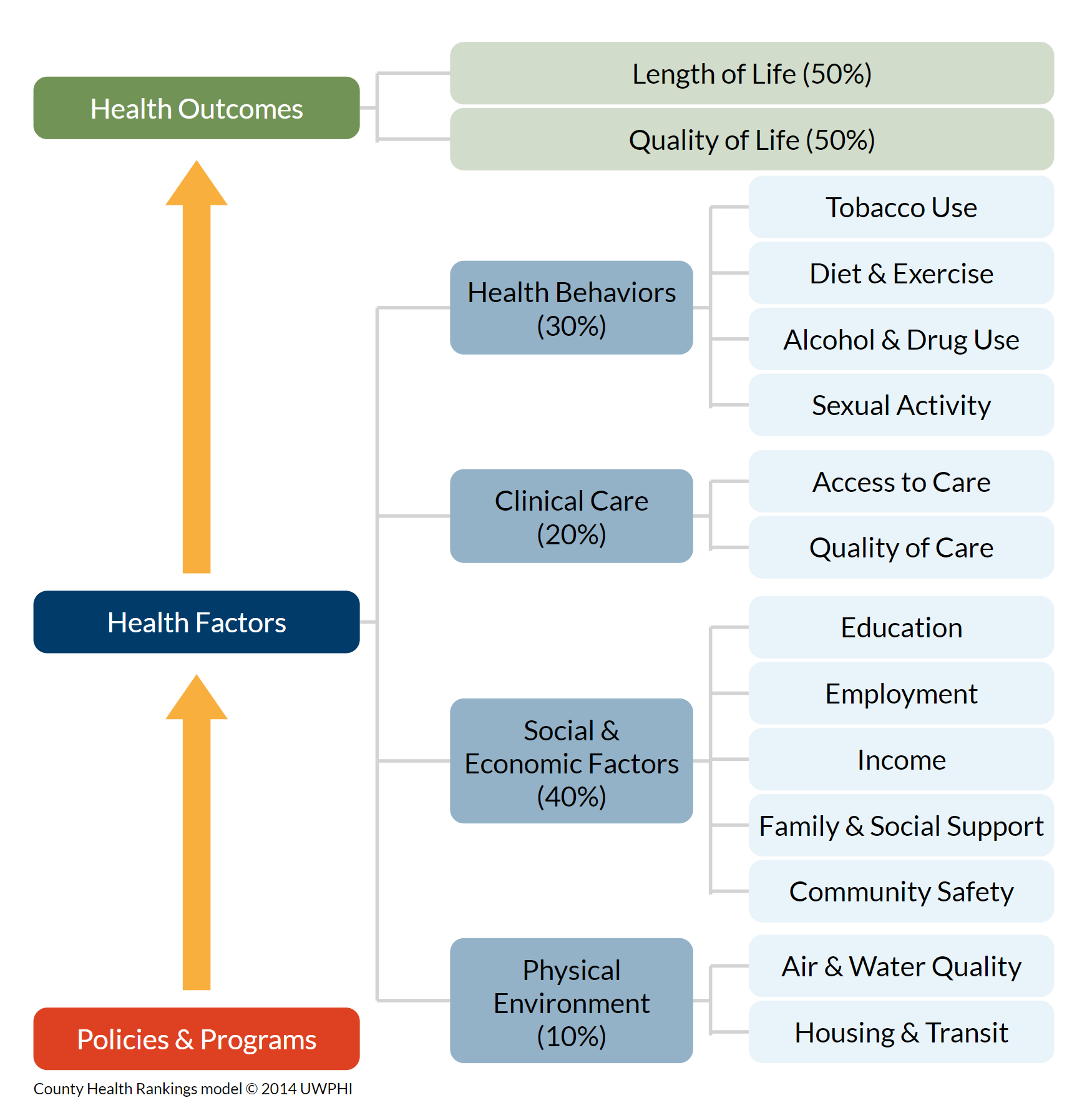

As you’ve already learned, health depends on much more than healthcare. Clinical care is clearly important – our diagnostic acumen, our efficacy in managing chronic conditions, and our procedural skills help patients every day. However, clinical care plays a smaller role in health outcomes than social and economic factors – experts have estimated that healthcare is responsible for only 20% of health outcomes.

from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation “County Health Rankings and Roadmaps” LINK

The social history helps us to understand the strengths and supports that could be incorporated into our patient’s care plan and to identify barriers to health that our interprofessional healthcare team and community partners could help to address. For example, a patient facing financial barriers to care could be referred to a hospital financial counselor for help identifying low-cost insurance or free care.

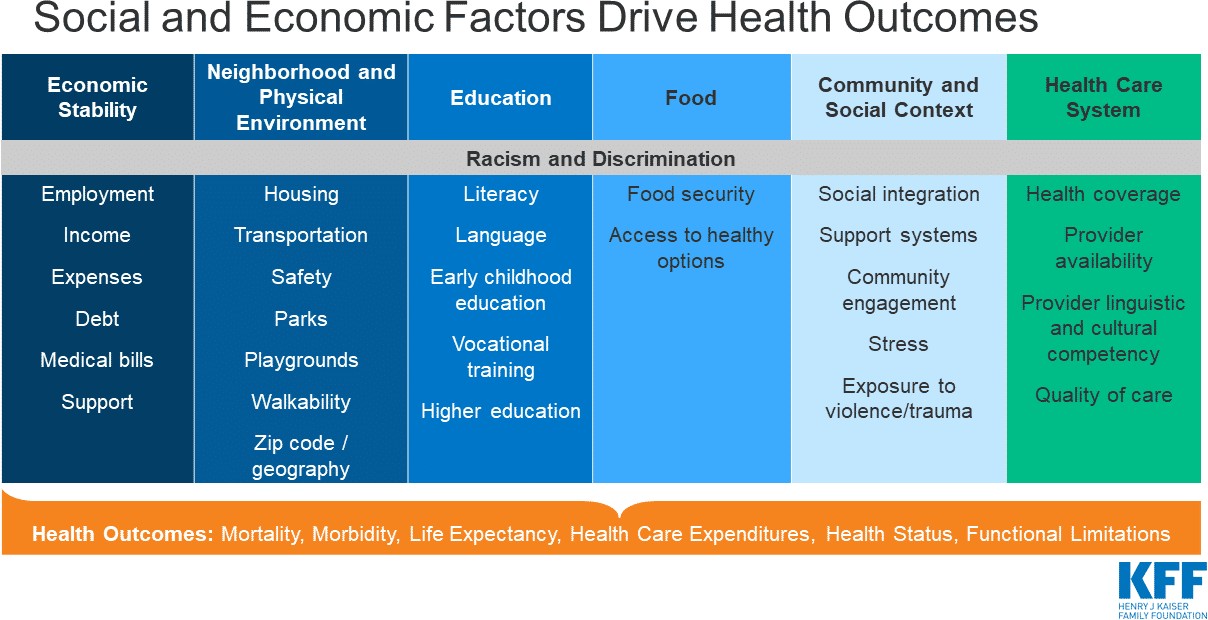

Understanding the strong influence of structural factors can also help us maintain empathy for our individual patients and lead us to advocate for and support the structural changes that could improve the overall health of our society. Health behaviors, social and economic factors, and the physical environment are all strongly influenced by inequities in the distribution of money, power and resources at the global, national, and local level. These inequities and the health disparities they cause are rooted in structural and systemic biases and racism across multiple sectors of our society.

As you learn about differences in health outcomes for racial and other groups, consider the intersecting social and economic inequities that could drive or exacerbate the different health outcomes. These inequities are almost always the underlying cause of health disparities. The image below is from the Kaiser Family Foundation – more information is available at kff.org

In the context of the patient interview, clinicians often ask about the factors that directly impact our medical decision-making and those that our healthcare team may be able to help with.

Social context & relationships

Social context & relationships

A patient’s social support system can have a profound impact on their health, and is often the starting point of the social history. “Who do you live with? Who do you turn to for support? What do you enjoy doing?” As a society, we rely on family and friends to provide a great deal of care. When a patient is admitted to the hospital, their social support network determines when they can be safely discharged from the hospital and where they will go. At home, friends and family often help with medications, therapy, transportation and self care.

But even before an illness, social connectedness clearly affects health. Social isolation and loneliness are associated with higher mortality, on the same order as substance use disorder or lack of access to healthcare. These effects on wellness have been shown to be so significant that community organizations and government programs are now starting to address loneliness and isolation, especially in elders. A hospital or clinic social worker can often connect people with these resources.

Housing & environment

A safe, well maintained and affordable home in a supportive community, with access to transportation, jobs, healthy food and medical care, promotes a healthy life. But due to economic and societal inequities, many of our patients don’t live in these conditions.

Homelessness has a particularly large impact on health, so it’s critical that we know if our patients lack stable housing. Those experiencing homelessness have disproportionately high rates of chronic illnesses, and without a home and a safe place to store medications, these can be very difficult to treat. Living on the streets or in a shelter also exposes people to infectious diseases, violence, malnutrition and harsh weather.

Exposure to air, water, and soil pollution also varies by neighborhood. In the US, pollution related illness is most common in minorities and in marginalized groups because sources of pollution have long been placed in these communities. Children are at particularly high risk, and even low level exposures early in life can lead to life long problems.

The process of assessing environmental health risk has a number of phases, starting with hazard identification (i.e.: “What is the exposure”, and then proceeding to exposure assessment (e: How much of the hazard is the patient exposed to?) and then risk assessment based on the hazard and the exposure (e: How Much health risk does the patient have from this hazard?).

Therefore, in the basic social history, it is appropriate to focus on hazard identification through a short number of screening questions about health hazards in the patient’s environment. If any hazards are identified, more detailed questions can be asked about how much exposure, in order to arrive at an assessment of risk from a particular hazard .

Access to healthcare

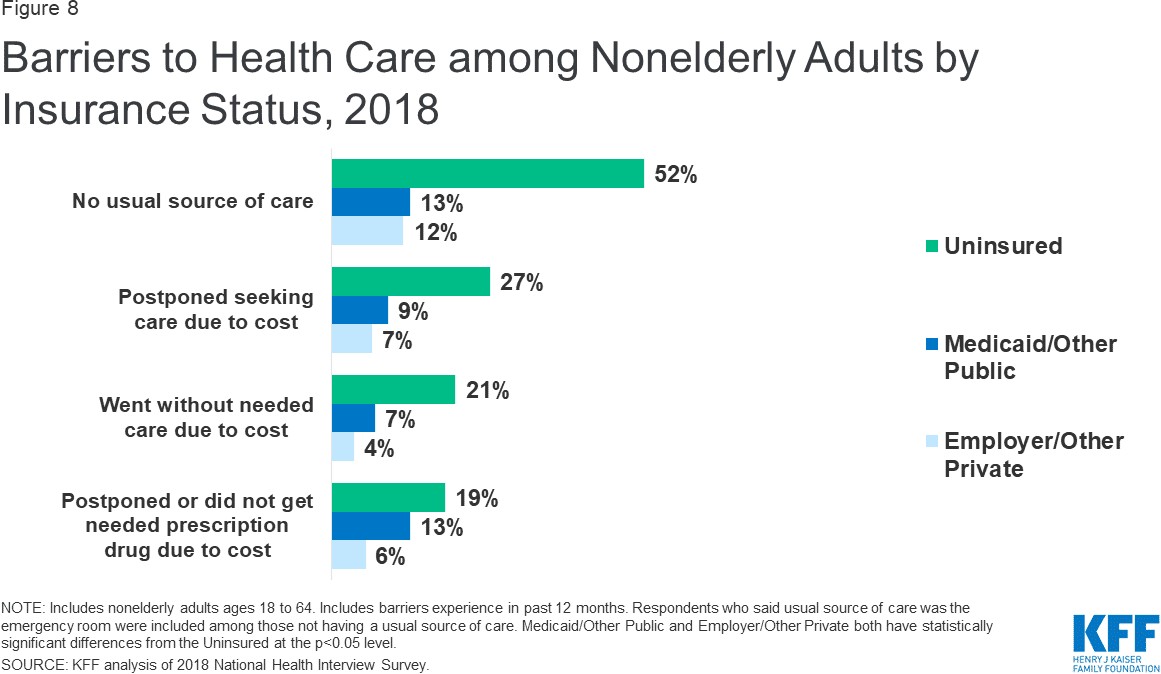

People with a usual source of care have better health outcomes than those who do not. Research has shown that an established relationship with a primary care provider is associated with receiving more appropriate medical care and lower all-cause mortality.

Access to primary care varies by location. Rural communities often lack access due to physician work force shortages and absence of healthcare facilities. Age-adjusted death rates for the top 5 causes of the death are higher in rural areas than in urban areas, and half of rural counties lack obstetrics services.

Access to care is also highly dependent on health insurance. The ‘safety net’ of public hospitals, community health centers, and emergency departments can’t close the access gap for the uninsured. With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the number of uninsured Americans fell from 44 million to 27.9 million in 2019, but lack of insurance is still a major barrier and the number of uninsured is growing again. Even for those who have insurance, the cost of health care can be a barrier, especially for families with low incomes or a pre-existing health condition. This graph is from the Kaiser Family Foundation, Key facts about the uninsured

Education

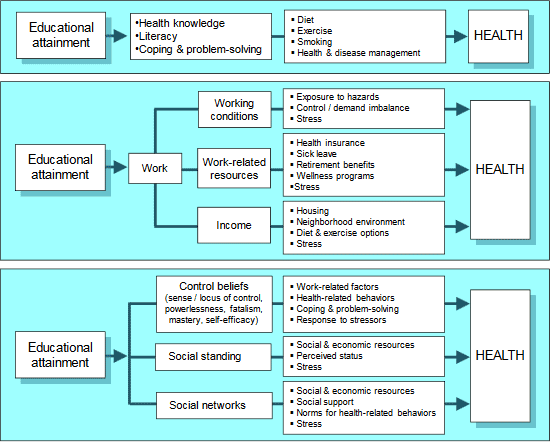

Education and health are clearly and strongly linked. People with a bachelors degree can expect to live about 9 years longer than those without a high school diploma, and those with more years of schooling are likely to have better health outcomes and to have healthier children. Many studies have shown that education improves health knowledge and health literacy, and understanding our patients’ educational attainment can help us adjust our approach to health and disease management. You’ll learn more this spring. The diagram below is from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Issue Brief: Education & Health

Other topics

Other topics may be addressed with some patients – you will learn more over the course of FCM.

| Topic | Situation | Sample questions in |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Adjusted to patient’s age & stage | Kids: Age specific safety questions & guidance at each well child visit. Elders: Geriatric assessment – you’ll learn more soon. |

| Safe firearm storage | Children live in or visit the home Suicidal or homicidal intent High risk of gun injury, i.e. cognitive impairment, severe mental illness |

Now I want to ask you a couple of questions about firearms. Are there any firearms in or around your home? If yes: Are the guns and ammunition locked up in some way? |

| Intimate partner violence | Based on available evidence, US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening “reproductive age women.” IPV also affects men and prevalence in trans people is high. Consider universal screening. | Often assessed with structured EHR form You can ask “Because difficult relationships cause health problems, we’re asking all our patients – do you feel safe in your relationship?” |

| Spirituality | Patients facing serious illness | Do you consider yourself spiritual or religious? What gives your life meaning? Are you part of a spiritual community? |

| Functional history | Age or illness with the potential to limit function | Often assessed with structured EHR form You can say “Tell me about a typical day for you. Are you able to do all the things you need to?” |

Social History at an Initial Visit: Example

Our patient with a severe headache has already shared quite a bit of her social history as part of the HPI. We’ve already learned that she’s married to her wife Sonya and has a high stress job running her own business. She had a very stressful situation at work yesterday. In this clip, the provider refers back to some of what she’s already heard and asks some additional questions about relationships, work and hobbies, access to care and financial concerns. Additional questions about intimate partner violence and home safety are part of the pre-visit questionnaire, which the physician reviewed before the encounter.

Resources & references

Deconstructing Biases and Racism in Medicine. Textbook of Physical Diagnosis: History and Exam. (UW NetID/login required)

Racism’s Hidden Toll, New York Times, 8/11/2020

A systematic review of reasons for and against asking patients about their socioeconomic contexts Moscrop, A., Ziebland, S., Roberts, N. et al. Int J Equity Health 18, 112 (2019).

Differences in Life Expectancy Due to Race and Educational Differences Are Widening and Many May Not Catch Up (2012). An article from the “Health Affairs” Disparities series

Neighborhoods and Health. Summary of issues and evidence from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Education and Health from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Excellent summary of evidence.

Social Factors Chapter 6 from “US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health.” A consensus study report from the United States National Academy of Medicine. Available online free.