Sim 1. Gathering Information

Diagnostic reasoning is one of the core skills of a physician. It begins with gathering information and leads to a prioritized differential diagnosis, the list of the most likely and most serious diagnoses that could explain a patient’s symptoms. With a prioritized differential in mind, doctors can judiciously choose diagnostic tests. Once a diagnosis is established, they can explain the problem and predict its course.

As an experienced physician hears about a patient’s symptoms, they recall illness scripts for diseases that could be the cause. Illness scripts are organized mental summaries of the signs and symptoms, risk factors and pathophysiology of a disease. Physicians develop them based both on formal education and on the patients they have seen. If a script aligns with the patient’s symptoms, that disease is added to the differential.

Recalling illness scripts can be automatic for familiar diseases or may require conscious effort for unfamiliar ones. Humans are believed to use two cognitive systems to interpret the information they gather. System 1 relies on pattern recognition—intuitive, efficient, and so quick that the reasoning process is subconscious. In contrast, System 2 is slow and deliberate, consciously analyzing information to reach a conclusion. This concept, known as dual process theory, can help us understand clinical reasoning and diagnostic errors.

Each cognitive system has its advantages and disadvantages. System 1 is fast, requires less cognitive effort, and is usually accurate for familiar problems. But System 1 is prone to jumping to conclusions. To avoid diagnostic errors, System 1’s first impressions can be double checked. System 2 is slower and requires more cognitive energy but can reason through a problem in the face of complexity and uncertainty. Experienced physicians rely on system 2 for unfamiliar, complex or high-stakes situations.

Gathering information: The First Step of Clinical Reasoning

In a 1975 study, physicians wrote down their leading diagnosis after the history, after the exam and after labs. When a final diagnosis was eventually made, the history had suggested it in 82% percent of cases. This study was repeated in the 1990’s with similar results. The physical exam and testing can confirm or occasionally suggest a diagnosis, but gathering the history is still the cornerstone of clinical reasoning.

As clinicians gather information, they try to identify patterns that suggest a disease or a type of disease. Important information is synthesized into a mental problem representation, a 1-2 line summary of the key features of a patient case.

”62 year old with acute cough”

Important new information is added to the problem representation as it is collected. By the end of the H&P, the problem representation above might morph to

“62 year old who recently received chemotherapy for breast cancer with acute cough, fever and hypotension”

This problem representation would quickly suggest sepsis due to pneumonia in an immunocompromised host.

Creating a Problem Representation

Experienced clinicians create problem representations without conscious thought but right now, it will take effort. Your goal is a concise and descriptive summary that leads to a differential diagnosis.

The problem representation typically includes patient demographics, the time course of illness and the clinical syndrome. To build your problem representation, ask yourself three questions:

Who? Patient demographics and predisposing conditions

The problem representation includes the age of your patient. Common causes of a given chief concern differ dramatically across the life span. For some problems, like lower abdominal pain, anatomic sex is also important. Appendicitis and diverticulitis can cause lower abdominal pain in all people but some people are also at risk for ovarian pathology or prostatitis.

Predisposing conditions are the medical problems, family history and social or environmental exposures that increase the risk of disease. For example, high blood pressure is a risk factor for heart disease and would be added to the problem representation for a patient presenting with chest pain. Recent incarceration increases risk for tuberculosis and would be added to the problem representation for someone with prolonged cough.

The problem list in the electronic health record (EHR) can help you identify predisposing conditions. Chronic illnesses, health behaviors and social factors that impact health may all be documented here. You can practice creating a problem list in our sims and review your patient’s problem list in PCP.

What? The clinical syndrome

The word syndrome is derived from the Greek word dramein, meaning to run, and the prefix syn-, together. A syndrome is a pattern of symptoms that together suggest certain diagnoses. They are often named with medical terms that you haven’t learned yet, like “monoarticular arthritis”. For now, think of your patient’s clinical syndrome as the chief concern plus any other symptoms that began at the same time.

Syndromes often incorporate semantic qualifiers— paired, opposing words that divide the causes of a problem into different groups. By making the problem representation more precise, they narrow the differential diagnosis and reduce cognitive load. Some semantic qualifiers apply to many chief concerns while others, like pleuritic and non-pleuritic, apply to a single problem (in this case, chest pain).

When? The time course of the problem

The time course can narrow your differential diagnosis. Diseases with similar symptoms may have different patterns of onset and progression. A patient’s symptoms can be described as hyperacute or sudden (developing over minutes), acute (present for hours to days), subacute (present for days to weeks) or chronic (present for 3-6 months or longer).

The pattern of symptoms can also can be described as constant or intermittent; stable or progressive; worsening or improving; relapsing, recurrent, or waxing and waning.

Build your repertoire of semantic qualifiers by pairing these commonly used terms.

Background reading: Back Pain

Before the simulation, you’ll need to do some background reading on back pain – medical knowledge is required to practice clinical reasoning! Because it is one of the most common chief concerns in primary care, back pain is a good place to start.

Please choose ONE of these resources to learn about common causes of back pain and the clinical features that differentiate between them. When you are done reading, return to this chapter to complete the Knowledge Check.

- Option A: Two pages from a journal review article on Low Back Pain. (PDF) Review articles from journals like American Family Physician and CMAJ can provide a concise and well-organized overview of common problems. The full article can be accessed here.

- Option B: The Up-To-Date chapter on the Approach to Low Back Pain in Adults. You can stop after “Initial Evaluation”. Up-To-Date is easy to access and this chapter is good, but it’s intended as a quick reference for practicing clinicians and some chapters are too detailed or fragmented to be good ‘background’ reading.

- Option C: Chapter 54, Low Back Pain from The Patient History: An Evidence Based Approach to Differential Diagnosis. This book is geared towards medical students and we’ll use it for future sims. The back pain chapter is more detailed than necessary for today but provides a great interview framework.

Knowledge check: Complete before class

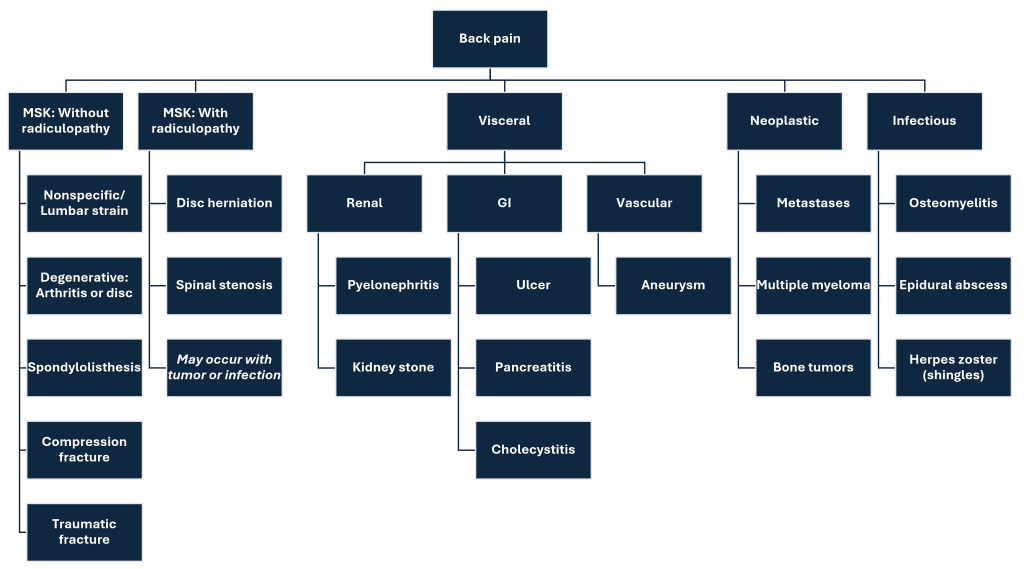

A branching diagram (sometimes called a diagnostic schema) is a way to categorize different causes of a problem. It can be based on anatomy, organ system, underlying pathophysiology or time course or it may be based on a construct specific to the problem. Here’s an example for back pain based on organ systems – it could be done many other ways.

After reading this patient story, create a problem representation by filling in each blank.

Fiona Atkins is in her primary care clinic today for an urgent visit for back pain. She was at the gym this morning for a strength training class when she attempted a pull-down. Right away, she had a terrible pain right in between her shoulder blades, in the middle of her back. She sat on a bench for 10 minutes hoping it would get better but when it didn’t, her friend needed to help her to the car and drive her home, then help her into the house and get her set up on the couch. She took two Percocet tablets she had left from a recent procedure but she couldn’t even get off the couch! That was her signal to come in. She hasn’t had pain anywhere except the middle of her back and hasn’t noticed any other symptoms. She felt just fine before she went to the gym.

Fiona considers herself to be healthy. She is 75 years old but has no chronic health conditions and takes no daily medications (the Percocet were for a recent dental procedure)

Based on your problem representation, what diagnoses are at the top of your differential?

Resources and references:

Problem representation overview. Journal of General Internal Medicine. Includes case examples that will make more sense after a few more blocks.

a summary that highlights the defining features of a case to guide the clinical reasoning process. It allows experienced clinicians to use pattern recognition to develop a Ddx quickly and helps learners to develop their reasoning skills.

the amount of information the working memory can process at any one time. Physicians can typically explore no more than a handful of diagnoses at once

worse with taking a deep breath

getting better and worse but never going away