Introduction to Primary Care

The Institute of Medicine defines primary care as “the provision of integrated, accessible healthcare services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnerships with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.”

Better primary care leads to better health outcomes. This has been demonstrated across health care systems and across nations since the 1960s. Most of the evidence supporting primary care is observational and it is hard to sort out the covariates, causation, and determinants of health, all of which are extremely complex. Nevertheless, a large body of evidence supports the substantial impact of primary care on health.

Life expectancy is higher in US states that have higher primary care physician to population ratios. Each additional primary care physician per 10,000 population is associated with an average increase of about two years in life expectancy.

Another study showed that American adults who called their personal physician a primary care doctor rather than a specialist had 33% lower cost of care and a 19 % lower risk of death.

In the United States, a study of Medicare beneficiaries in fair or poor health showed that one of the strongest predictors of a preventable hospitalization was living in a primary care shortage area. Areas with better primary care have better health outcomes including lower total, cardiovascular and infant mortality as well as earlier detection of colorectal, breast, uterine and cervical cancer.

Interprofessional Teams in Primary Care

The World Health Organization defines interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) as “multiple health workers from different professions working together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care.” The primary care practicum is an opportunity to observe and participate in an authentic interprofessional healthcare team very early in your medical education.

Core competencies for practicing as an interprofessional team are listed at right. These competency domains, developed by the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) guide learning for collaborative practice across health professions education.

Your PCP experience will allow you to observe and practice teamwork and communication, which improve both patient safety and health professional well-being (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2023).

Gaining an understanding the roles of other health professionals will help you contribute to your PCP team and succeed in clerkships. At almost every clinic, you will work with at least one other health profession. Many practices have a team-based care model that includes a variety of different professionals to meet the needs of their patients.

Your team members may include:

Medical assistants

Medical assistants provide direct, in-person patient care and address a multitude of between visit care needs. A medical assistant is typically responsible for rooming a patient, obtaining vital signs, briefly reviewing patient concerns and updating portions of the medical record. Additional clinical duties may include performing EKGs, administering immunizations, and assisting with procedures. In many clinics, medical assistants also develop long-term continuity relationships with patients and are integral in helping with between visit acute and chronic care management, fielding and responding to patient messages and making followup calls.

Registered nurses

Registered nurses are involved in many aspects of patient care. A key role is the triage of patient concerns, directing them to the most appropriate site of care. RNs are integral in health education, care coordination and follow-up of clinical care interventions. RNs develop continuity relationships with patients and help to manage chronic medical conditions which require frequent follow up such as diabetes, heart failure and hypertension. In the in-person setting, RNs may be involved in caring for and transferring unstable patients, wound care management, and administering medications among other things.

DNPs

In the primary care setting, DNPs evaluate, diagnose and treat patients for most common problems. They have first trained as registered nurses and then completed a doctorate of nursing practice program, sometimes after years of practice as a nurse. They have prescriptive authority and can order medications, tests and equipment in the same way as physicians and in some states, they can practice independently. In general, DNP programs do not include as much pathophysiology as medical schools and require less clinical practice before licensure. More complicated primary care patients may require consultation with a physician in the practice and the most complex may be transferred to a physician for ongoing care.

Physician assistants/associates

Physician assistants or associates complete a two-year training program after practice experience working in another field of health care, for example as a respiratory therapist or military medic. The first training programs, established in the 1960s, used the term physician assistant but more recently, physician associate has been used (you may see both). Like DNPs, these professionals evaluate, diagnose and treat primary care patients for most common problems and they also have prescriptive authority. They must work with a physician but see many patients independently. They may consult with or transfer the care of more complex patients to physicians. DNPs and PAs are sometimes referred to as ‘mid-level’ providers but we discourage the use of this term.

Clinical pharmacists

Washington state law allows clinical pharmacists to see patients for independent visits for common chronic illnesses, including diabetes, hypertension, and warfarin anticoagulation. Under collaborative drug therapy protocols, established with the prescribers in the clinic, pharmacists initiate, monitor, and modify drug therapy for specific diagnoses. Patients achieve therapeutic goals more quickly and with fewer provider visits. Pharmacists can also provide patient education, medication reconciliation, and identify resources for patient unable to afford their drugs.

Social workers.

Social workers assess patients’ and families’ strengths & needs and identify resources to meet those needs, within the clinic or healthcare system or in the community. These needs are diverse and may include issues around insurance, housing, mental health, substance use disorders, caregiver support systems and grief among many others. Licensed social workers may also provide short term counseling services in some clinics

Mental health specialists.

Many clinics have integrated mental health or behavioral health specialists given the prevalence of mental health issues in both primary and specialty care. These specialists may be psychiatrists, psychologists or licensed social workers. Many of the behavioral health programs in the primary care setting aim to provide guidance around medication management, mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy tools to help with mood disorders, and provide more immediate support while patients are transitioned to a mental health provider who can provide a longer-term therapeutic relationship.

Dietitians

Dietitians work with patients to assess nutritional status, counsel on eating habits, diet modifications, and healthy lifestyle and provide education on nutrition for disease management.

Patients and families

Even patients who are seen frequently in the clinic spend most of their time at home, managing their own health with the support of family and community. Research shows that the ability and willingness to manage one’s own health, often called patient activation, is associated with better control of chronic illness and fewer new diagnoses.

Working in partnership with our patients can increase their activation. Strategies like collaborative agenda setting, asking permission to provide information and tailoring it to their needs, motivational interviewing and negotiating the treatment plan have been shown to increase a patient’s willingness to actively manage their health.

A patient’s healthcare team may also include professionals outside the walls of your clinic. They may see a pharmacist at their local community pharmacy, a visiting nurse in their home or a dietitian or medical sub-specialist in another location. These professionals, as well as any others they see from the list below, should be considered part of a patient’s outpatient team. Although it may not always happen in our fragmented health system, all team members would ideally be looped in on decisions that may impact or are related to the care that they provide. A copy of a clinic note or a phone call for major issues can prevent unsafe gaps in care.

Acute Problem-Focused Visits

At an acute visit, a new problem is assessed in the context of the patient’s overall health. Since time is limited, the information you gather is problem-focused for the chief concern.

The HPI is gathered in the usual way – starting with the patient’s story then filling in gaps with focused questions, guided by your differential or by the organ system that seems to be affected.

For other sections of the CMD, collect and document only information that is ‘pertinent’, meaning that it’s somehow related to possible causes of the chief concern. If you can review your patient’s Electronic Health Record, look for pertinent information in the past medical, health behavior, social and family histories and confirm it with them. If you do not have EHR access, ask about ongoing health issues, medications and allergies as well as health behaviors that could contribute to the problem at hand.

For example, consider a patient coming in with one week of cough. Since the differential diagnosis for cough includes postnasal drip, bronchitis, pneumonia or GERD, you’d gather data that would help to differentiate between these illnesses. After eliciting the HPI, you would ask about a history of conditions that could relate to cough, like allergies, asthma, other lung disease or GERD. Pertinent health behaviors would include tobacco exposure and social history could explore other environmental irritants. Pertinent review of systems questions would be about fever, nasal congestion, shortness of breath, chest pain, or acid reflux. This information could be collected in the short time available for the average clinic visit.

For acute problems, the physical exam is also guided by your differential diagnosis or the organ system(s) that may be involved. You will almost never perform a ‘head-to-toe’ exam in PCP. be hypothesis driven. For a chief concern of cough, the problem-focused exam would include the nose, oropharynx and chest.

Chronic Disease Management Visits

Sixty-four percent of American adults have at least one chronic illness and 12% have 5 or more. Seniors carry the heaviest burden. The most common conditions in those over 65 are hypertension (58%), hyperlipidemia (47%), arthritis (31%), coronary artery diseases (29%) and diabetes (27%). Fewer children have chronic conditions. Untreated dental caries is the most common and causes the most lost school days. ADHD affects 9% of people under 18, followed by asthma (8%), anxiety (7%) and depression (3%).

The purpose of a chronic disease management visit is to assess and update the status of the illness, identify any complications, and adjust treatment as needed. The goal is not a differential diagnosis as it would be for an acute problem. Rather, it is an understanding how well the disease is managed, how it is impacting your patient’s life, and how you can work together to optimize control while minimizing the side effects of treatment.

Problem-focused history for a chronic disease visit

Background: onset of illness, current prescribed treatment, and any complications.

Interval history:

- symptom & symptom control

- self monitoring and results (i.e. blood glucose, home BP measurment)

- visits with other providers since last visit

- recent tests

- related hospitalizations

Adherence: medications, health behaviors, other interventions

Functional status: activity tolerance and ADLs, quality of life

Social support & psychosocial concerns

Patient goals

Adherence to medications and/or lifestyle measures is required to control chronic conditions and non-adherence is extremely common. An estimated fifty percent of prescribed medication doses are missed and lifestyle changes can be even harder to stick with. If a chronic condition is not controlled, nonadherence should be explored as the cause first. Escalating therapy without recognizing non adherence is costly and can be dangerous if a patient suddenly begin taking all prescribed medications at once. Most non adherence is intentional rather than ‘forgetting’.

Common contributors to non-adherence include:

- Fear of potential side effects

- Misunderstanding the need for medicine

- Lack of symptoms. I feel fine – why am I taking this?

- Depression is associated with more non adherence

- Cost may lead people to ration or not fill prescriptions

- Worry about becoming dependent on a medication

- Mistrust of the doctor’s motives or of the healthcare system

- Complexity – the more medications prescribed and the higher the dosing frequency, the more likely a patient is to be unable to take medications as prescribed.

Patients with chronic conditions are at risk for physical, cognitive and social limitations that can affect both their quality of life and their ability to manage their illness. Relationships and social roles can help or get in the way of patient self-management and something that’s changed at home is often the reason for worsening control of a chronic condition. Revisiting and expanding the social history, exploring the patient’s goals, strengths, responsibilities, stressors and insurance is especially important when things aren’t going the way you had hoped. Depression is also more common than in the general population and most clinics screen regularly with a questionnaire like the PHQ-2 or PHQ-9.

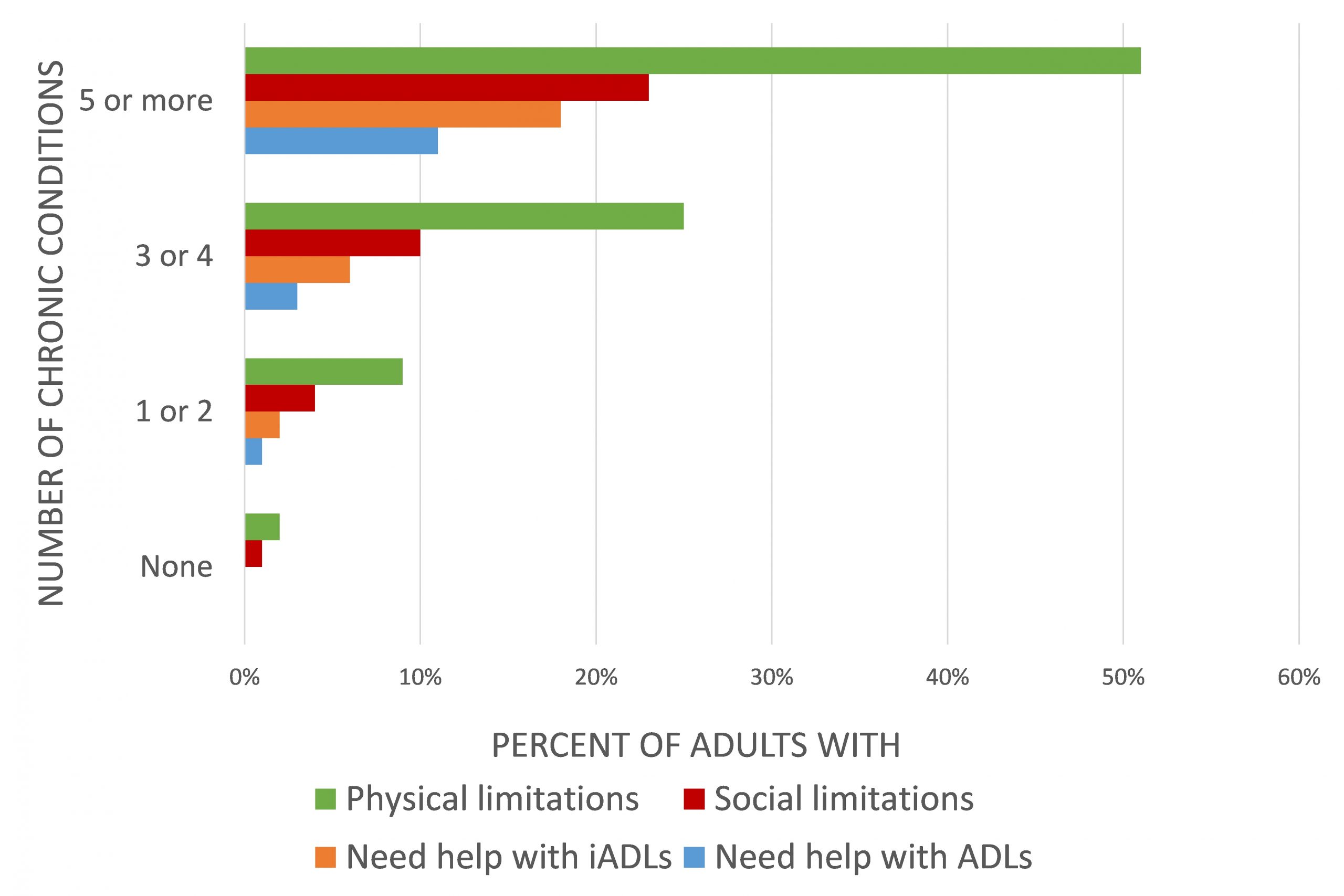

A simple way to enquire about functional status is to ask your patient to describe a typical day and ask whether help is needed to complete usual tasks. You can also ask whether there’s anything they’d like to be doing that they aren’t currently able to. Both social and physical limitations are closely correlated with the number of chronic conditions, and interventions like physical therapy referrals or community support visits can help people maintain their independence.

At a chronic disease management visit, the physical exam is used to assess how well is the disorder controlled and to identify any complications. The exam that you will perform is disease specific, for example a lung exam for a patient with known asthma or testing sensation in the feet for someone with diabetes.

Screening and Prevention Visits

The purpose of screening & prevention or ‘wellness’ visits is to identify and implement health maintenance interventions appropriate for an individual patient. These may include certain physical exams, tests, immunizations or lifestyle changes. Recommendations are often based on demographic information including age and sex assigned at birth but they are also influenced by health behaviors and other health conditions.

Patients may bring up other conditions they’d like to discuss during the wellness visit. Use agenda setting to identify these concerns and negotiate what can be accomplished during the visit. You may need to plan for a follow up visit to address these other concerns.

Screening: Learning points from Research Methods/FMR

- Screening refers to the detection of disease during the preclinical phase, which is the period after biological onset but before recognizable signs or symptoms are detected.

- Diagnosis refers to the identification of disease during the clinical phase, in which the disease has already exhibited detectable signs or symptoms.

- Diseases appropriate for screening require a preclinical phase that can be detected by testing and are typically harmful if left untreated.

- Detection of a disease at an early stage by testing should provide meaningful benefit.

- Considerations for evaluating the health impact of a screening test include validity, reliability, prevalence of the disease, follow-up procedures, safety, and cost.

The US Prevention Task Force (USPSTF) provides up to date recommendations from an expert panel of clinicians and public health experts. Bookmark the link or download the app for use in your PCP. Based on evidence for the benefits and risks of each preventive service, the USPSTF assigns a grade of A, B, C, D or I. Services receiving a Grade or A or B should be recommended or provided while Grade C interventions are recommended for selected patients based on clinician judgment and patient preferences. The USPSTF recommends against interventions graded D and I means there is insufficient evidence to assign a grade.

- Grade A recommendations: There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial

- Grade B recommendations: There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

- Grade C recommendations: The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small.

Skills for PCP. Setting the agenda

Agenda setting can be the key to a successful clinic visit, with patients and clinicians deciding together how to spend their time. All concerns are put on the table up front so worrisome issues don’t ‘pop up’ at the end of the visit and patients can prioritize what they most want to address. Agenda-setting has been shown to shorten primary care visits without decreasing patient satisfaction because people remember that their concerns were addressed, not the actual time they got to spend with the doctor.

- Indicate the time available. “We have 20 minutes for our visit today. Let’s start by talking about how to use our time together”. Avoid using “only” as in “we only have 20 minutes today” which can make the time seem shorter.

- Forecast plan for the visit. “We scheduled this appointment to followup on blood pressure so we’ll take a look at that plus anything new that’s come up”

- Elicit patient concerns. “What do you have on your list today” or “What were you hoping we could address today” followed by “And what else” until the patient has nothing else to add.

- Negotiate, prioritize and summarize. If you think there is enough time to address all the agenda items, summarize them and begin. If not, prioritize the ones that are most urgent and those that are most important to the patient. Make a plan to address other concerns on another day.

The video below, created at the Mayo Clinic, shows a dermatologist and a patient setting an agenda in a specialty visit. All videos like this are a little corny, but it gives you the idea.

Skills for PCP. SOAP Notes

In PCP and clerkships, you will use the S-O-A-P structure for outpatient and followup notes. Electronic health records may import additional information collected by other providers or at other times but the note YOU write is still guided by S-O-A-P. Remember that most patients can access their electronic health records and may read any notes that you write. You can use medical terms in your notes but be cautious about language that could alarm or confuse your patient and remember the best practices for patient-centered communication that we discussed in Immersion.

S: Subjective

Subjective refers to the problem-focused history that you gathered from the patient or reviewed in the medical record and confirmed with the patient. It begins with the ID/CC (the reason for the scheduled visit) followed by the HPI plus any other pertinent past medical, health behavior, social or family history. It should be in paragraph(s) rather than divided into sections like hospital write-ups. If more than one problem is discussed at the visit, the subjective section of the note should have a separate, numbered paragraphs for each issue addressed.

O: Objective

Objective refers to the problem-focused physical exam you performed plus any related diagnostic tests or imaging. This section should include:

- Vital signs

- The findings of the problem-focused physical exam, organized by system and including the presence or absence of findings pertinent to the CC

- Results of recent tests or imaging studies

Assessment

Assessment is your interpretation of the information you presented in the subjective and objective sections. For an acute problem, it will be a differential diagnosis, which should include at least 2-3 reasonable possibilities justified with information presented in the S & O section, similar to hospital write-ups.

For a chronic disease visit, your assessment should discuss current control, complications and any goals or barriers to control that you and your patient identified.

Plan

The plan describes next steps after the visit and should be developed in collaboration with the patient to be sure that it will work for them. A specific plan for follow up should be included in every note.

- Diagnostic tests: Labs, imaging or functional tests like spirometry in COPD

- Treatment: Medications and health promoting behaviors

- Education: By the provider or other members of inter professional team

- Follow up: With primary care, specialty referrals and other community resources

The plan for a chronic disease management has the same 4 elements as other visits, emphasizing education to optimize patient self-care at home. Education is key in chronic illness and many patients would benefit from more than can be accomplished in a 15 minute follow up. As you meet other health professionals in PCP, ask about their roles in patient education.

In many clinics, medical assistants act as health coaches and educators, ensuring patients understand next steps and self-care at the end of a visit. Registered nurses can provide chronic disease education either to individuals or groups. Pharmacists can teach people about their medications and address adherence with strategies like motivational interviewing, simplifying drug regimens or developing reminder systems. Dietitians are experts in nutrition education and motivation and social workers can help address addiction, finances, stressors and other barriers to care.

The problems in the “assessment/plan” section correspond to those listed in the subjective section. When more than one problem has been addressed, many physicians write the assessment and the plan together for each one.

Documentation for screening & prevention/yearly wellness visits

The primary documentation for these visits is different. It typically includes updating the past medical history, family, social, sexual, health related behaviors, allergies and medication list. You will also document any preventive health and wellness measures that were discussed based on the patient’s age, sex assigned at birth and other medical conditions or risk factors. These are often documented in an electronic form rather than a note.

Skills for PCP. SOAP OCPs

Outpatient OCPs are presented in the same format as the SOAP note and will ideally 3-5 minutes long.

- Subjective: ID/CC + problem-focused history, organized by problem if more than one problem is addressed

- Objective: Vital signs + problem-focused physical exam + labs and imaging

- Assessment: Always include an attempt at formulating an assessment even if you’ve only had a minute or two to pull your thoughts together. This helps your preceptor know what you are thinking and provides them the opportunity to give specific guidance and education.

- Plan

Consider ending your oral case presentation with a ‘learning question’ to guide your preceptor’s teaching: “My learning question is…”

- Will you confirm the lung exam with me?

- How would I differentiate bronchitis from a URI?”

- Under what circumstances would we send someone with a head injury to the ER?”

Here, Dr. Natalia Filipek (E16) presents an outpatient OCP that address an acute problem, a chronic medical condition and some preventive health.

Skills for PCP. Telemedicine

Telemedicine is defined as the use of technology to deliver healthcare at a distance and in your PCP, you may observe or participate in Telehealth visits. Your clinic may also use telemedicine asynchronously, for example patients sharing data like blood glucose logs or heart rhythm monitoring for review and advice on next steps with a secure message or phone call.

Specific patient consent is required for telemedicine. Patients must agree to receive care on the virtual platform and to have their insurance billed. Clinic staff often complete this consent process before the provider begins their visit. Key elements of this consent include:

- You cannot provide the same evaluation as in a face-to-face visit, and an in-person visit may be requested by either the provider or the patient.

- Technology is encrypted and secure, but no technology is 100% hack-proof.

As with in person visits, the clinician starts by introducing themself by name and role, ensuring comfort and privacy for the patient, and asking if they are comfortable conducting the visit where they are. They may specifically ask if anyone else is in the room, and if the patient would like them to join the visit.

Technology should be optimized before starting the history, with each participant in a quiet and well-lit room, sitting away from windows and bright light to avoid shadows. Cameras should be adjusted to show the whole face and many physicians hide “self view” to keep focus on the patient. “Eye contact” is made by looking directly at the webcam to convey “eye contact”.

In this video, Dr. Calvin Chou of the Academy of Communication in Healthcare demonstrates patient-centered communication in a video visit.

Tele-physical exam

The physical exam will (obviously) be more limited in a telemedicine visit, but there are creative ways to maximize the utility of the exam. If you are participating in telemedicine visits in your clinic, use these resources for ideas.

- The Telehealth 10: A Guide for a Patient-Assisted Virtual Physical Exam.

- Stanford Medicine Videovisits. Problem focused-exams for upper respiratory infection, low back pain, and shoulder pain.

Knowledge Check

Agenda-setting

Gathering Information: Chronic Disease Visit

Screening & Prevention Recommendations

Imagine you are seeing a 58 y.o. cisgender female patient for a Wellness Visit today. She is 5′ 4″ and weighs 185 lbs. She has a 25 pack year history of smoking and quit 3 years ago. She uses alcohol occasionally and no other substances. She is in a monogamous relationship with her long-term cisgender male partner. She exercises occasionally. You note she has had regular COVID and influenza vaccines but has no other immunizations documented in the past 5 years.

Use the USPSTF Prevention Task Force tool to identify 5 screening recommendations and that you would consider today

Use the CDC Adult Immunization Schedule or one of the vaccine apps on immunize.org to identify any immunizations that you would consider today.

Note these potential recommendations below.