Neurologic exam

Benchmark exam you should be able to demonstrate on completion of FCM:

Assess mental status

- Level of consciousness

- Orientation

Assess cranial nerves II-XII

- Test visual acuity and visual fields for each eye alone (CN II)

- Test pupillary reaction (CN II and III)

- Test eyelid opening (CN III)

- Test extra-ocular movements (CN III, IV, VI), observing for nystagmus (CN VIII)

- Test facial sensation & muscles of mastication (CN V)

- Test muscles of facial expression (CN VII)

- Test hearing (CN VIII)

- Test palatal rise to phonation (CN IX and X)

- Test sternocleidomastoid & upper trapezius muscle strength (CN XI)

- Test tongue protrusion (CN XII)

Assess motor function

- Evaluate strength and bulk of:

- Upper extremity muscle groups: Shoulder abductors, arm flexors and extensors, wrist flexors and extensors, finger flexors, finger abductors

- Lower extremity muscle groups: Hip flexors, extensors, abductors and adductors; knee flexors and extensors, foot dorsiflexors and plantar flexors

- Assess for pronator drift

Assess reflexes

- Upper extremity: Biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis

- Lower extremity: Patellar, Achilles and plantar

Assess sensation

- Compare light touch on the bilateral arms and legs

Assess cerebellar function

- Finger to nose test

- Heel to shin test

- Gait

- Romberg test (tests sensation and cerebellar function)

Hypothesis driven maneuvers (Term 3)

- If you suspect cognitive impairment, perform the Mini-Cog

- If you suspect a disorder of the eye or visual pathways, test visual fields.

- If your patient reports sensory changes, assess multiple sensory modalities

- If you suspect an extrapyramidal disorder such as Parkinson’s disease, assess muscle tone.

Immersion: Mental status

Your patient’s level of consciousness will quickly become clear during your interview – are they alert, confused or sedated? Note their speech and awareness of their current situation.

To formally assess mental status, ask your patient their full name, location and date. Decreased level of consciousness and confusion are much more common in the hospital, and mild cognitive impairment is common in the elderly. In these situations, formally assess orientation to person, place and time, as Dr. Taylor demonstrates below.

Immersion: Cranial nerves

The 12 cranial nerves control the motor function, sensation and special senses of the head and neck. The steps below test all but cranial nerve I, which is responsible for smell and isn’t usually tested in the clinic. You’ve already practiced testing visual acuity, pupillary reactivity and hearing as part of the head and neck exam. Now practice them again alongside the other cranial nerves, to cement your knowledge.

| CN | Primary function(s) | Tested by assessing |

| I | Smell | Not usually tested |

| II | Vision | Visual acuity in each eye Pupillary reactivity to light Visual fields |

| III | Eyelid opening, eye movements, pupillary function | Eye movements Pupillary reactivity to light |

| IV | Eye movement | Eye movements |

| V | Muscles of jaw, sensation of the face | Jaw clench Sensation in upper, mid, lower face |

| VI | Eye movement | Eye movements |

| VII | Muscles of facial expression | Raising eyebrows, smile, frown |

| VIII | Hearing and balance | Hearing finger rub |

| IX | Sensation of throat, middle ear, back of tongue | Palate rise with phonation |

| X | Too complicated for this table | Palate rise with phonation |

| XI | Muscles of the neck | Head turning |

| XII | Tongue muscles | Tongue protrusion |

Immersion: Motor exam

To assess the motor system, test the strength in each major muscle group as demonstrated in the video above. Motor strength and bulk are compared side to side, and strength is graded on a 0-5 scale. Functional testing with heel and toe walking is an alternative method of testing strength in the legs.

Test each of the following muscle groups, stabilizing above the joint with one hand and comparing side to side.

Upper extremity:

- Shoulder abductors

- Arm flexors and extensors (biceps and triceps)

- Wrist flexors and extensors

- Finger flexors and finger abductors

Lower extremity:

- Hip flexors, extensors, abductors and adductors

- Knee flexors and extensors

- Foot dorsiflexors and plantar flexors

Weakness can be a finding of central or peripheral motor neuron disease or disorders of the neuromuscular junction or muscle. Atrophy suggests disuse of the muscle or lower motor neuron disease.

Pronator drift is a subtle sign of arm weakness. The patient is asked to hold their arms out, with palms up, and eyes closed. If one arm is weak, it will ‘drift’ into pronation, with the palm turning down

| Grading Strength |

|---|

| 0 = no contraction |

| 1 = visible or palpable contraction with no movement |

| 2 = moves with gravity eliminated |

| 3 = moves against gravity but not against resistance |

| 4 = moves against resistance but less than full power |

| 5 = Full strength |

Immersion: Sensation

Sensory testing is most helpful when your patient’s history suggests a neurologic concern. To screen for a sensory nerve problem, you can compare sensation to light touch side-to-side on the proximal and distal upper and lower extremities. Because sensation is subjective, a detailed sensory exam is not performed unless your patient reports sensory changes or you suspect a problem affecting sensation. You will learn to do a more detailed sensory exam during the Mind, Brain and Behavior block.

The Romberg test assesses the sensory inputs that allow people to stand upright and can be performed along with gait testing.

Immersion: Reflexes

As you learned in anatomy, spinal reflexes are involuntary movements that occur in response to a stimulus. Tapping a tendon with a reflex hammer stretches it. This stretch is detected by sensory afferents that relay the signal to the CNS. The signal runs peripherally through the dorsal horn of the gray matter to synapse on a motor efferent. The motor efferent returns to the same muscle, causing it to contract.

Reflexes are tested to differentiate causes of neurologic symptoms. Problems with the central nervous system can increase reflexes while problems with peripheral nervous system or muscles decrease reflexes.

To test deep tendon reflexes, swing the reflex hammer from your wrist to strike and stretch the appropriate tendon, observing for contraction of the muscle. If you can’t elicit a reflex, try augmentation maneuvers:

-

- For upper extremity reflexes: Clench the jaw and counts to 20

- For patellar reflex: Hook the fingers of the right and left hands together and pull.

- For Achilles reflex: Presses down lightly on your hand, as if ‘stepping on the gas

| Assess each of the following reflexes, comparing side to side | |

| Upper extremity deep tendon reflexes | |

| Biceps | With your patient’s arm flexed and the forearm supported, place your thumb over the biceps tendon. Watch for biceps contraction as you strike your thumb with the pointed end of the reflex hammer. |

| Triceps | Your patient’s arm may be positioned with the hands on the hips OR flexed and pulled across the chest OR supported with the forearm hanging down. Strike the triceps tendon with the pointed end of the reflex hammer 2-5 cm above the medial elbow, observing for contraction of the triceps muscle. |

| Brachioradialis | The brachioradialis muscle runs from the lateral elbow over the dorsal arm to the thumb. Strike the radial side of the forearm above the wrist with the flat end of the hammer or place your thumb over the brachioradialis tendon and strike it with the pointed end. Watch for movement of the belly of the muscle around the elbow. You may also see a twitch of the thumb. |

| Lower extremity deep tendon reflexes | |

| Patellar | Place your hand on the quadriceps and strike the patellar tendon on the front of the leg below the knee. Watch for extension of the leg or feel for contraction of the quadriceps. |

| Achilles | With your patient seated and the feet hanging freely, support and dorsiflex one foot. Tap on the Achilles tendon in the back of the ankle with the flat part of the reflex hammer, observing for plantar flexion of the foot. |

| Plantar reflex | This is a ‘superficial’ rather than a deep tendon reflex. Draw a hard object lightly along the lateral foot from the heel forward and medially across the ball of the foot, observing movement of the big toe. If there is no movement, repeat with slightly firmer pressure. |

Grading reflexes

Deep tendon reflexes are graded on a 0-4 scale. Reflexes in healthy people can range from absent to exaggerated. All would be considered ‘normal’ if they are symmetric and unchanged from prior exams.

Reflexes that are asymmetric or have changed from baseline are abnormal. Reduced or absent reflexes suggest lower motor neurondisease or sensory loss. Exaggerated reflexes that are asymmetric or changed suggest upper motor neuron disease.

| Grading Deep Tendon Reflexes |

| 0 = absent |

| 1 = present but less than average |

| 2 = average |

| 3 = increased |

| 4 = clonus |

Plantar reflex

The normal plantar reflex is downward movement of the toes, usually most visible in the big toe. Slow upward movement of the toes is abnormal and indicates a problem with the brain or spinal cord. If the patient is ticklish or uncomfortable, they may withdraw the foot – this is uninterpretable (that’s why you should start with light pressure.) The normal response can be documented as “Toes are downgoing bilaterally.”

Immersion: Cerebellar Exam

The cerebellum integrates sensory input and coordinates movement. Weakness, numbness, or vision problems will interfere with your patient’s ability to perform all of these tests.

- Finger-to-nose test: Holding your hand in front of the patient, ask them to touch their nose then your finger, going back and forth. Observe for smoothness and accuracy, comparing the right and left sides. Unilateral incoordination indicates a problem with the cerebellum on that side

- Heel-to-shin test: Ask the supine patient to place one heel on the opposite shin, and run the heel up and down the shin. Observe for smoothness and accuracy, comparing the right and left sides. Unilateral incoordination again indicates a problem with the cerebellum on that side

- Gait: Ask the patient to walk across the room, turn and walk back. Then ask them to walk heel to toe in a straight line. Gait abnormalities can be caused by weakness, loss of sensation, or cerebellar problems. Healthy people over the age of 60 are often unable to heel-to-toe walk.

- Romberg test assesses the ability to stand upright with the feet together. This requires intact cerebellar function plus at least two out of three sources of sensory input: vision, vestibular function (CN VIII), and position sense of the joints. The patient is asked to stand with the eyes open and the feet together, with your hands at either side of them to catch them if they sway or fall. If they are not able to do this with the eyes open, a cerebellar problem is likely. Then ask them to close the eyes, again spotting them.

- At least two of these sensory inputs plus a functioning cerebellum (which pulls it all together) are required to maintain balance

Immersion: Exam Video

Dr. Breana Taylor, a neurologist and Cascade College faculty, demonstrates a complete neurologic exam assessing all 6 domains, including visual acuity, visual fields, and hearing, which you also saw demonstrated in the Head and Neck exam. These can be performed in either section depending on the patient’s chief concern but you only need to do them once.

Immersion: Sample Documentation

Sample documentation of a detailed neurologic exam

Mental Status: Alert and appropriate, oriented to person, place, and time.

Cranial nerves:

II: Visual acuity 20/30 (tested with pocket visual screener)

III,IV,VI: Full extraocular movements

V: Masseter strength intact, sensation intact to light touch

VII: Symmetric facial expressions

VIII: Hearing intact to rubbed fingers bilaterally

IX,X: Palate elevates symmetrically with phonation

XI: Strong head turn and shoulder shrug bilaterally

XII: Tongue protrudes symmetrically

Motor Function: 5/5 strength in distal and proximal muscle groups in both upper and lower extremities. No pronator drift.

Deep Tendon Reflexes: Reflexes 2+ and symmetric at biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, patellar, Achilles. Toes downgoing bilaterally.

Sensation: Intact to light touch sense in upper and lower extremities.

Cerebellar Function: Finger to nose and heel to shin intact bilaterally without dysmetria.

Gait: Stable

Immersion. Knowledge Check

Term 1. Exam in hospital bed

Many of your hospital patients will not be able to sit or stand. Here Dr. Taylor recommends adaptations to the motor and reflex exam for patients who are supine in bed.

Term 3. Abnormal findings

Mental status

Decreased level of consciousness:

- Lethargy: Patient is sleepy, requiring stimulation to maintain an awake state.

- Stupor: Patient cannot be aroused to a fully awake state but may respond semi-purposefully to stimulation.

- Coma: Patient demonstrates no purposeful response to any type of stimulation.

Abnormalities of language or speech:

- Aphasia is a disorder of language caused by stroke and other brain disorders affecting the language areas of the cortex. It manifests as problems with comprehension, fluency, naming, arithmetic and/or writing. You will learn more in the section on Communication in Disability.

- Dysphonia is a disorder of speech, specifically voice production caused by abnormal larynx or vocal cord function.

- Dysarthria is a disorder of speech, specifically articulation caused by abnormal motor control of the pharynx, palate, tongue, lips and/or face.

Cranial nerves

Anisocoria

Pupillary size is determined by the balance of parasympathetic and sympathetic input. The parasympathetics constrict the pupil and arrive at the eye via CN III. The sympathetics dilate the pupil and arrive via the nerve plexus along the internal carotid artery.

To determine the cause of unequal pupils, compare the degree of asymmetry in light and dark. If the degree of asymmetry is:

-

- The same in light and dark: The patient has physiologic anisocoria, a normal variant occurring in 20% of the population. An old photo can confirm it’s longstanding

- Greatest in light: The patient has a parasympathetic problem in the larger pupil. Look for other signs of CNIII dysfunction, especially EOM weakness

- Greatest in dark: The patient has a sympathetic problem in the smaller pupil. Look for other signs of Horner syndrome, decreased facial sweating and ptosis.

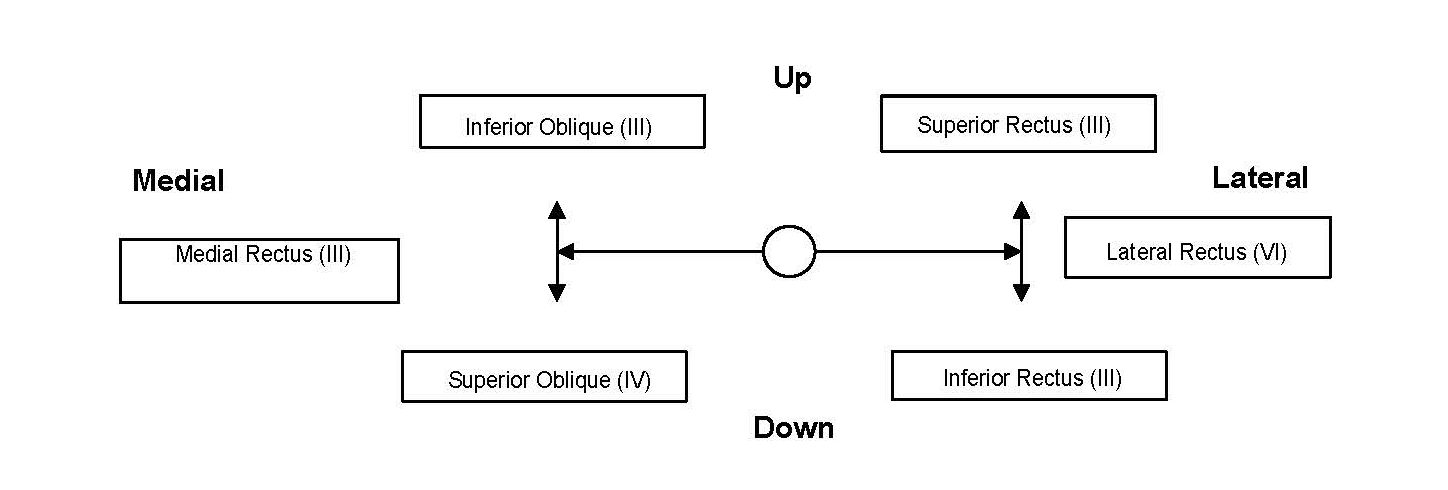

Extraocular muscle weakness.

You may identify this on exam or your patient may report of diplopia with EOM testing. Diplopia can indicate more subtle weakness than you can see. The muscles responsible for movement in each of the 6 cardinal directions is shown below, for the left eye.

Facial weakness

Unilateral facial weakness can be caused by either a central or peripheral lesion of the 7th cranial nerve. These can be differentiated by how much of the face is involved.

The motor neurons innervating the forehead receive input from both sides of the brain, while those innervating the lower face receive input only from the contralateral brain. A peripheral facial nerve lesion (Bell’s palsy) causes weakness of both the upper and lower face, as in the image at right A central facial nerve deficit, which is usually caused by stroke, will affect only the lower face.

Tongue weakness.

Each genioglossus muscle pushes the tongue out and to the opposite side, so the tongue deviates to the side of weakness. Unilateral atrophy and twitching are also signs of weakness.

Motor system

Increased tone

There are two types of increased muscle tone: rigidity, which is caused by extrapyramidal disorders like Parkinson’s disease, and spasticity, which is caused by central nervous system disease. Rigidity can be an early and diagnostically useful finding in Parkinson’s and other extrapyramidal disorders. Patients with spasticity usually have other findings of upper motor neuron disease, like weakness and upgoing toes. In this short video, Dr. Kraus differentiates the two.

Term 3. Hypothesis-driven exam maneuvers

If you suspect cognitive impairment, perform the Mini-Cog.

- Give your patient a list of three items like Apple-Penny- Ball. Ask them to repeat immediately and remember them for 5 minutes.

- Give the patient a piece of paper with a circle drawn on it. Instruct them to draw a clock, placing the numbers on the clock face, with the hands pointing to a certain time. Then ask them to recall the 3 items.

- Three item recall and mini-Cog (for more on scoring the Mini-Cog)

- Recall of 0 items indicates cognitive impairment.

- Recall of 1-2 items with an abnormal clock face indicates cognitive impairment.

- Recall of 1-2 items with a normal clock face indicates no cognitive impairment.

- Recall of all 3 items indicates no cognitive impairment.

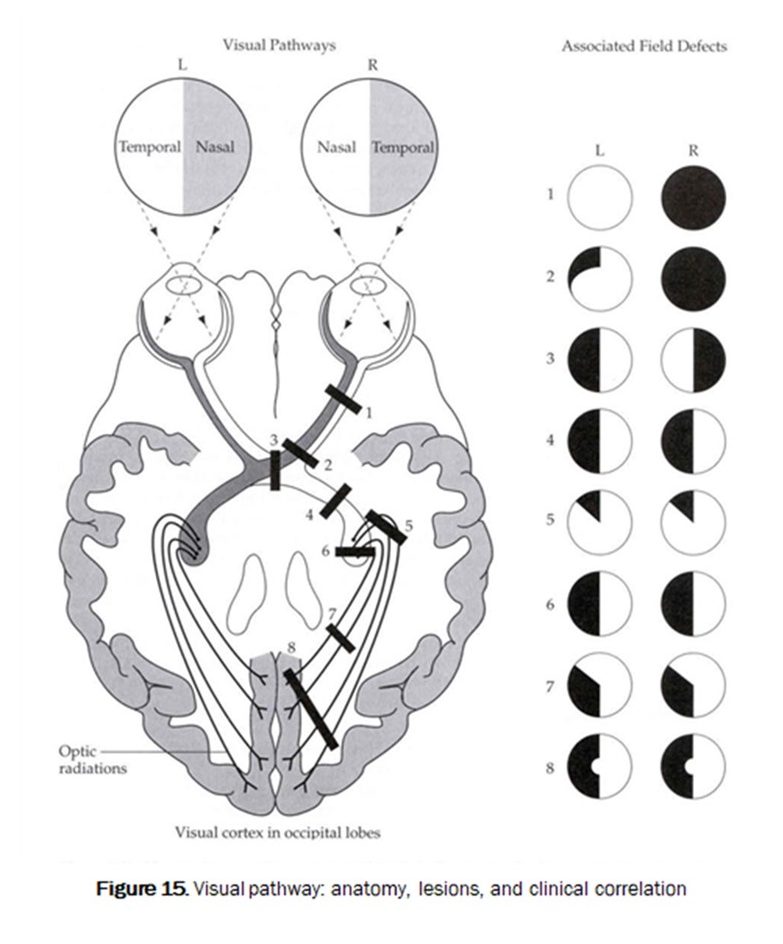

If you suspect a disorder of the eye or visual pathways, test visual fields.

Abnormal visual fields can be caused by problems anywhere along the visual pathways. Here’s a recap of Dr. Kraus describing and demonstrating.

Lesions at different locations cause characteristic patterns of visual field loss. Diseases localized to the eye can cause loss of peripheral vision (as in glaucoma) or complete loss of vision in that eye. Optic nerve lesions, pituitary tumors that compress the optic chiasm, and brain lesions lead to different patterns of visual field loss.

If your patient reports sensory changes, assess multiple sensory modalities:

The goal of a more detailed sensory exam is to localize the abnormality to an anatomic site.

- Light touch and pinprick are carried in the spinothalamic tract. Break a clean cotton swab in half. Use the soft tip to assess light touch and the sharp handle for pinprick.

- Vibration sense is tested with the 128 Hz tuning fork.

- Proprioception is tested by moving the joint.

Clues to localization of the problem:

Brain or brainstem. Findings include sensory loss in large parts of one side of the body that can’t be explained by a single nerve or dermatome. Light touch and pinprick are good modalities to test, looking for symmetry from side to side.

Spinal cord. Findings include a sensory level on the trunk and asymmetric findings of vibration/proprioception loss on one leg with pinprick loss on the other. Light touch, pinprick, vibration and proprioception are good modalities to test in the legs. Light touch and pin are good modalities to find a sensory level on the trunk.

Peripheral nerve. Findings include a length-dependent sensory loss or sensory loss in small parts of one side of the body that can be explained by a single nerve or dermatome. Light touch, pinprick, vibration and proprioception are good modalities to test for a length-dependent process. Light touch and pin are good modalities to find a focal nerve process.

Term 3. Putting it all together

When patients present with neurologic symptoms, your exam is used to localize the cause of their findings, which could range from the brain to the neuromuscular junction. Localization narrows the differential diagnosis and directs next steps in testing. Here, Dr. Kraus gives an overview.

Term 3. Knowledge Check

none for now.

Clinical: Adaptations for children

By Anisha Chandra Schwarz, MS MD

The adult neurological exam is a systematic clinical tool which is among the most beautiful examinations in medicine. Although most of the same holds true when performing the neurological exam in a child, some key points may differ, and these bear mentioning so that you have the best chance of successfully obtaining a reliable exam. Target your exam to the clinical question, as you may have limited time to examine a child.

Please never say or write, “The patient had no neurologic exam,” or “I could not get a neurologic exam,” especially if the reason for the statement is that the patient is an infant, a child, or has significant developmental delay or disability. Every patient of every age has a neurologic exam. In many cases, you have already done many portions of the neurological exam by careful observation during your general exam, so take credit for these by reporting them.

Obtaining the History

Unlike in adults, most children cannot give a full history without the help of a parent (or guardian). This person is an invaluable resource when it comes to accurately relating how events unfolded. That said, you must remember that the parent may harbor their own loving perceptions about or fears for their child. Your role in gathering the history with a child’s parent is to mentally construct a narrative that enables you to independently generate a localization for the problem and a differential diagnosis, which will help to guide your examination and further narrow the location and nature of the problem.

In order to secure the interest and cooperation of both parent and child, an open conversation with the parent at some physical distance from the child is usually the least threatening way to begin.

One common approach is to address the child and parent together, introduce yourself, and explain that you will allow the parent to discuss their concerns first, then the child, before the exam. That said, children have varying attention spans and interest, so especially if they are tired or hungry, putting the exam at the beginning of the visit may make sense rather than attempting to coax an exhausted or cranky child. Reassure the child that the examination will not hurt. Do not promise a painless experience if there is any chance you will be ordering a blood draw after the visit! Simple rewards, such as the promise of stickers, are helpful for younger children.

Older teens deserve the same considerations as adults (to be addressed directly and to see you as their physician), and those over 14 should have the chance to speak with you alone if desired. For older teens, make it a routine part of your history to politely offer to excuse the parent from the room for a few minutes to give the teenager a chance to bring up any potentially embarrassing concerns.

Developmental Considerations

In addition, children come with the added challenge of rapid development. Part of your role is to tease out whether the child’s history and exam is appropriate for her chronological age. For anyone under one year old, the gestational age at birth and perinatal history is very relevant. This will inform which reflexes you expect to find, how you test strength and coordination, and which milestones you expect the patient to have reached. The OFC (occipito-frontal circumference) is a sensitive, though not specific, measure of growth that can serve as a vital sign. For children of any age, language and speech development (include sign language and other non-English languages) both serve as insights into cognitive development.

Ask parents about developmental milestones by asking open-ended questions, such as “What sounds or words are you hearing? Any signs?” or “How is your child moving around? How does your child play with small toys?” Then you can ask further clarifying questions such as “Does she use two fingers or her whole hand to pick up the toy?” Try not to ask whether a child has yet reached a particular milestone as the initial question; many parents feel a bit defensive at this.

In the beginning, rather than trying to memorize each and every milestone and reflex (key ones are found in table below under Reflexes), it is best to simply gather detailed information about the child’s motor, verbal, and social development, as well as to perform an exam geared towards either infants (up to 12 months) or older children (similar to an adult). Most typically developing children can start to do a standard neurologic exam by ages 6 or 7. In the next few sections, you will find some specific tips and tricks for examining children.

Examining a Child: Introduction

The most important difference between examining a child and examining an adult is the role of observation and play. To many learners, it may seem as though pediatric neurologists watch a child for a while, play with her for a few minutes, have her run around in the hall, tap on her reflexes, watch a cute video on the parents’ phone, and declare the exam complete. Indeed, that is the impression we are hoping to convey to the child, and to cause as little distress as possible. However, critical information can be gleaned from careful observation.

For example, many cranial nerve palsies are readily apparent through playing and speaking with a child. Strength differences and asymmetries may also come out in playful interaction, but only if you are watching for them. It is difficult to do a systematic, confrontation exam of sensation or strength in a specific order in a young child; instead, learn to store away the information gleaned from interaction as it becomes available, and reorganize it in a way that you and others can easily interpret. Reflex testing may precede fundoscopy and cranial nerve testing may need to follow an active gait examination in a child with “the wiggles”, but try to always organize and present your notes in the usual manner.

Some portions of the exam are unique to babies (see section at the end). The best place to practice examining healthy babies is in the newborn nursery and at the many well checks that take place in the first year of life, and at the homes of willing friends. This will enable you to recognize what is abnormal.

If possible, try to involve the parents in the exam. Have them close by, or holding the child. Explain what you will do before you do it. Some portions must be done without the parent. For instance, gently coach them not to answer for the child during direct questioning; you are not wondering what the child actually had for breakfast; you are trying to see whether the child remembers and can tell you! Often, offering options will interest the child and they will participate more readily: “Would you like to check your eyes with a flashlight first, or go run in the hall?”

Mental Status and Language

Comment on the resting state of the child and what type of stimulus it took to get them to the most alert and awake state possible. Infants who have just eaten are likely to appear quite somnolent, and this can affect their entire exam; likewise infants who are hungry can appear quite jittery. Ask when an infant most recently fed; this can be reported as part of mental status. For language, remember a child should speak one word at a time by one year, two-word sentences by two years; three word sentences by three; able to produce long and mostly grammatical, intelligible sentences by four. Vocabulary should increase exponentially. A two-word sentence comprises two distinct words (i.e., “thank-you” counts as one, “no, thank-you,” counts as two). Words in ASL count. Sounds count as long as they are specific to a certain concept (such as “Ro-Ro” for the family dog and all dogs). Bilingual words count as one, i.e., “savon” in French and “soap” in English are the same concept. It is not true that bilingual children develop more slowly, or that younger siblings develop more slowly.

Developmental history should go into your history, but observed aspects of development (for instance, how fluent/how many words are said per sentence) should go into the appropriate section of the exam (usually mental status or motor).

Mental status questions should be appropriate to the age and stage of development. To test orientation, naming, memory, and attention, try asking about colors, objects in the exam room, cartoon characters, school friends, plush toys, what they had for breakfast, identity of family members and teachers, or the name of their school. Children over 5 may be able to give you their home phone number or address.

Vocal quality can be gleaned through videos in a very shy child. Some dysarthria is normal until about five; healthy toddler dysarthria is different from slurred speech and has a specific quality. Often, /l/, /r/, and /w/ may be conflated.

Cranial Nerves

Acuity can be tested with toys and stickers across the room; often not better than this. Hearing can be tested by whispering instructions and by air conduction with a tuning fork. Extraocular motions can be tested with a toy. Fundi are best done in a slightly sleepy child at the end of the exam, or one who has the energy to participate and focus. Have them look at a parent who can prompt them to keep their eyes pointed at the parent during fundoscopy. Facial strength may be checked by blowing air through a pinwheel or making funny faces. Playing with a flashlight can give you a pupillary exam, a tongue exam, and a palate exam. Asking the child to copy your facial expressions is the quickest way to obtain a cranial nerve exam in a young child.

Motor Exam

Bulk can be tested by look and feel in the child. Comment on whether muscles feel appropriate versus too rubbery or fibrous.

Tone must be tested in a resting muscle. In babies, tone is paramount. Compare central/axial tone to limb/appendicular tone (see section on infants at the end of this chapter). Check the ability to hold the head up in an upright and prone position.

A crying child will activate their muscles, rendering a tone exam useless. Try to check their limbs casually while they are focused on something else, such as watching a cartoon or eating. A velocity-dependent increase in tone is called spasticity. Check for it slowly first, then quickly, in arm extension and leg flexion.

In order to check strength, functional testing is often the easiest – that is, having the child mimic you through a series of motions. For example, a child who can squat, rise from the floor without using her arms, climb onto the exam table, bend over to pick something up without falling, jump, run, hop on one foot, and do it all symmetrically, is unlikely to have significant lower extremity weakness. In older infants and toddlers who are uncooperative or afraid, pushing gently on arms and legs often prompts them to push you away, giving you a rough idea of their limb strength and symmetry. By pinning the proximal portion of the limb, you can attempt to isolate a muscle group. Use a small toy or ball for them to push at or kick for the same purpose, as many children are afraid to push or kick against an adult.

Sensation

As in adults, you can check light touch, temperature, proprioception and vibration in a child. Light touch can be done with a paintbrush or gauze – have the child close their eyes and guess where the paintbrush is, or say “now” when they feel it. Check temperature by asking them to tell you which of two water cups is colder, or whether the floor or your tuning fork is colder, etc. Look for any cuts or burns that the child did not notice. Do not check pain in an awake child unless you have a specific reason to. Proprioception: many children can perform a Romberg; but help them cover their eyes or they will likely peek. Proprioception in the fingers can be screened for by having the child close their eyes (or have parents cover), and then touch their nose with the selected finger. In addition, a child who can walk down the hall while playing a game on an iPad likely has intact proprioception! Vibration sense is more difficult; often all you can tell is that the child feels it. However, a child that truly has dorsal column dysfunction should have other signs on exam, such as an abnormal gait (sensory ataxia), and difficulty with proprioception.

Reflexes

Similar to testing in adults. Remember that children have, in general, “jumpier” reflexes than adults. 1-2 beats of clonus can be normal in a child. You can test most reflexes with a finger over the tendon so that it does not hurt. In addition, you can check reflexes in children that are often difficult to obtain in adults, such as pronator (C6) at the wrists and medial hamstrings (L5). The latter is helpful in a child who refuses to turn over for the exam and lies face down on the bed or ground. Triceps (C7) can also be easily tested in a child lying face down, as can Achilles (S1) and the plantar response. Use your thumbnail, not the pointy tip of your hammer, to check the plantar response, as many children have a very strong withdrawal of the foot that will fool you if you use too noxious a stimulus.

If you are not getting any reflex at all, check that you are in the correct place. It takes practice, also, to allow the reflex hammer to swing down with gravity on the tendon rather than applying force. All the force should be in the upswing, and none in the downswing except to guide the hammer to the correct location. This is both the correct method and less painful. Start by using your wrist’s full range of motion (this standardizes your exam because it is always the same length); if very brisk, you can use smaller and smaller arcs to see what the least amount of necessary force may be to elicit the reflex. Primitive reflexes are discussed at the end of this chapter.

Gait

Most children love this portion of the exam. Go with the child or have the parent do this as well if needed for moral support. Have them walk, run, jump with one and two feet, heel walk, and toe walk. A three-year-old can jump with both feet. Tandem walk is usually difficult before the age of four. Skipping is a complex gait task that requires strength and coordination; many children cannot skip until 5-6 or older, but it is a useful screening tool – intact skip excludes severe gait abnormalities. Pay attention to how the arm is held (older walking infants and young toddlers hold arms up in high guard) and whether arm swing is symmetric. Toddlers have a wide-based gait which disappears around three. Remember: roll at 5 months, sit at 6 months, crawl or creep at 7 months, pull to stand at 9 months (often cruising along furniture), walk at 12 months. There is a lot of normal variation; these are just guidelines.

Coordination

In most children, this can be easily observed while playing with the child and doing the rest of the exam. Look for tremor, dysmetria while reaching out for a toy, truncal unsteadiness or titubation, gait issues, and intrusive movements, especially in limbs, neck, and eyes. Remember that as babies myelinate, they can display all kinds of movements that would be abnormal in an adult, including dysconjugate gaze, jerky or jittery motions, choreiform movements, and truncal/neck unsteadiness. Vertical or rotary (circular) nystagmus are never normal.

Babies Under 12 Months

Certain portions of the exam are specific to babies. Tell the parents what you are about to do and be gentle; one of the greatest fears in life may be that someone will hurt your baby. Watch a more experienced physician before you attempt your first newborn exam.

For general exam: Remember to check the OFC in every baby you examine, and trend it along the growth curve. Check the anterior fontanel for size, tension (how full or soft it feels), and pulsatility. Examine the tone and reflexes while the baby is in either a “quiet awake” or sleepy state (or feeding). Important baby anatomy includes: the soft palate (use your gloved finger and check the suck reflex at the same time), the sacrum (dimples or tufts), genitalia, and skin (looking for melanotic cyanosis, hemangiomas, or other birthmarks). Look at the face and fingers/toes for dysmorphology; compare the child to parents to avoid bias. A child who looks nothing like her biological parents and also has facial features that appear atypical to you may have a genetic syndrome or teratogenic/infectious exposure in utero. Hirsutism varies greatly and is less helpful, but reporting it shows you are paying attention. The more babies you see, the more easily you can do this.

Cranial nerves: Few people check acuity, olfaction, or hearing in a baby. Check extraocular motion using the child’s mother as a target. Move the child relative to the mother or the mother relative to the child, remembering that newborns see only about a foot away. Dysconjugate gaze is normal in the newborn, and usually only disappears after the first several weeks of life. You can overcome the vestibulo-ocular reflex in the normal newborn, so it is not as useful.

For motor exam: Tone in a baby is checked axially (central tone, including neck) and appendicularly (limbs). Check head lag by lifting the supine child gently off the bed by her arms. Never allow a baby’s neck to quickly or forcefully extend; support the head with your forefingers as you hold the child. Check neck control and shoulder “slip through” by suspending the child vertically/axially over a soft surface with your hands underneath the axillae. A child with very low central tone will literally slip through your hands, so be prepared to grab them!

Hold the baby prone over the bed to check neck extension. Remember, a baby with high tone may appear to have head lag when supine, but when you turn them prone, they will extend their neck against gravity and hold their body up and horizontal. A baby with low tone will curl into a C shape facing the floor, because they cannot resist gravity.

Strength in a baby is described as how frequently they move and how easily they resist gravity and gentle pressure from an examiner. Report it in each of the four limbs and head.

Reflexes will be higher on the side to which the head is turned, so check them with head midline. Remember the usual ones as well as rooting, suck, Moro (report as absent, one, two, or three phase), fencer’s (atonic neck), palmar grasp, and plantar grasp. The usual plantar responses are upgoing for the first year. Check startle by clapping near the baby.

Coordination: Differentiating normal movements from seizures in a baby can be subtle. They are usually asymmetric as the nervous system is not mature enough for rapid generalization. Look for forced gaze deviation, hemibody stiffening, or movements that repeat with a baby that looks distressed after them. Seizures in newborns can be subclinical. Seizures can be associated with desaturation and bradycardia, but these can also cause seizures. Threshold for obtaining an EEG in a neonate is lower than in an adult.

Gait: In older infants, have them try to roll, crawl, cruise, or whatever they can do to move under their own power. Motivate them by carrying them away from parents and have them try to return. Children are unlikely to leave a parent and come to you on command for the first year of life.

In general, given that milestones may be difficult to memorize over the course of a single rotation and that infants change so quickly, a detailed description of what you did and saw, categorized in the usual way (General/MS/CN/Motor/Sensory/Reflex/Gait/Coordination) should paint a picture in the mind of your listener and will make you very effective as a future child neurologist.

| Commonly Checked Reflexes in Babies |

|---|

| Asymmetric tonic neck reflex – when the head is turned to one side, the legs on the same side will extend, and the opposite limbs contract, mimicking a fencing pose. The asymmetrical tonic reflex should disappear around six months of age. |

| Tonic labyrinthine reflex – when the head is tilted back, the back arches, the legs straighten, and the arms bend. Tonic labyrinthine reflex should disappear by three-and-a-half years of age. |

| Galant reflex – when the infant is supported on its stomach, stroking along one side of the spine causes lateral flexion of the lower body to that side. Spinal gallant reflexes should disappear between three and nine months. |

| Palmar grasp reflex – when the palm is touched, the fingers grasp around the object touching it. Palmer grasp reflex should disappear around four to six months. |

| Placing reflex – when an infant is supported in an upright position and the back of a foot touches the surface, the leg will flex. Placing reflex should disappear by five months. |

| Moro (startle) reflex – when the infant’s support is suddenly removed, the arms abduct, then adduct. Moro reflex should disappear by six months. |

| Commonly Checked Milestones in the Neurology Clinic (All these vary, but some guidelines:) |

|

|---|---|

| Babbles (consonants) | 6 months |

| Say first word “mama” | 9 months |

| Say two-word sentences | Age 2 |

| 50% intelligible by stranger | Age 2 |

| 100% intelligible by stranger | Age 4 |

| Raking grasp | 5 months |

| Transfer across midline | 6 months |

| Pincer grasp | 10 months |

| Head control | 2 months when prone |

| Rolling | 4 months |

| Sitting | 6 months |

| Crawling/Creeping (optional) | 7-8 months |

| Pull to stand | 9 months |

| Cruising (walk holding on) | 10 months |

| Walking (independent steps) | 12 months |

| Jumping with two feet | Age 3 |

| Commonly Checked in Babies | |

|---|---|

| Social smile | 2 months |

| Head up while prone | 2 months |

| Laughing | 4 months |

| Rooting | 4 months |

| Sucks | Varies, can be longer |

| Moro | Until 4 months |

| Stepping (baby held upright with feet on bed) | 6 months |

| Fencer’s | Until 5 months |

| Palmar grasp | Until 5 months |

| Plantar grasp | Until 10 months |

| Plantar reflex | Until 12 months |