MSK 2. L-spine, Knee, Hip, Foot & Ankle

The approach to examining the musculoskeletal system is similar across joints. The affected and contralateral side are inspected and palpated carefully, observing for side-to-side differences. Range of motion and strength testing may be followed by joint-specific exam maneuvers to differentiate between two possible causes of the problem. In FCM, we will introduce a few of these ‘stability and special tests’ but we don’t expect you to master them until you use them routinely in clerkships. Focus on developing a consistent approach to the basics.

Inspection

- Observe alignment and relative sizes of the areas of interest, at rest and in motion

- Observe any erythema, swelling, ecchymosis, deformity, or skin lesions

Palpation

Use a systematic approach to palpation of:

- Joint

- Soft tissue

- Bursae

- Tendons

- Muscles

- Ligaments

- Bony Prominences

Range of motion

- Active range of motion – the patient moves the joint

- Passive range of motion – the examiner moves the joint

Strength testing

- Muscles that move the joint, and in some cases, the joint above or below it.

Stability and special tests as directed by the differential diagnosis

For every joint, there are many stability and special tests that could be performed to differentiate between possible causes of your patient’s problem. Their sensitivity and specificity often varies based on examiner skill and different physicians often prefer and use different tests.

Neurovascular testing

In Immersion, you will apply the general approach to the musculoskeletal exam to the lumbar spine.

In Term 2, you will practice the exam of other joints commonly assessed in primary care. Only the Lumbar Spine, Shoulder and Knee exams are included in the FCM Benchmarks.

Cardinal signs of MSK disease

The cardinal findings of MSK disease may be identified on any regional exam. Inspect and palpate carefully and don’t forget to compare the symptomatic to the contralateral joint.

Swelling: Visible swelling of a joint suggests synovial inflammation or joint effusion. Maneuvers specific to each joint can help to further evaluate for subtle effusions especially in the knee.

Swelling of the surrounding soft tissue could be caused by infection or trauma. Sometimes swelling of these areas can be subtle. Loss of skin wrinkling or joint landmarks can be signs of swelling.

Warmth: Compare the temperature of one joint to the other and to the surrounding muscles. Joints should be cooler than the surrounding muscles. Warmth to palpation of a joint suggests inflammation which could be due to an inflammatory condition or infection.

Atrophy: Localized muscle atrophy suggest prolonged damage to that specific muscle group or the nerve supply.

Tenderness: Evaluate for tenderness over different anatomical structures including bones, joints, tendons and bursa.

- Joint line tenderness may suggest arthritis.

- Bony structure tenderness suggests traumatic injury, inflammation, or infection.

- Tenderness at a bursa suggests bursitis.

- Tenderness of a tendon suggests tendinitis. Pain with passive stretch or resisted motion of the tendon support tendonitis.

Decreased range of motion: Active range of motion refers to the patient moving the joint themselves, while passive range of motion refers to the examiner moving the joint. Intraarticular problems cause pain with both active and passive ROM – it hurts to move an injured joint whether the patient or examiner is moving it. Tendon and muscle problems typically cause more pain with active ROM, when the tendons and muscles are actively engaged in moving the joint.

Decreased ROM can also be caused by stiffness or prolonged disuse of any cause. Increased ROM may be due to joint laxity.

Weakness: It is important to test all muscle groups in the impacted area and compare to other side. Strength testing should be documented as for the neurologic exam.

Immersion: Lumbar Spine Video

Low back pain is one of the most common reasons for primary care visits and the exam of the back is the most straightforward regional MSK exam. Please watch this video overview – we’ll practice the low back exam in class to cement the approach to the MSK exam.

Term 2. Lumbar Spine Benchmarks

Inspect: From the back and the side, observing spine curvature, muscle bulk, and symmetry of hip and shoulder height

Palpate: Observing for tenderness, spasm, and asymmetry:

- Vertebrae from L1 to the sacrum

- Paravertebral muscles bilaterally

- Sacroiliac joints

Range of motion: Assess flexion, extension, lateral rotation, side bending

Neurovascular testing: To assess for compression of nerve roots or spinal cord, test

- Lower extremity strength

- Lower extremity reflexes

- Lower extremity sensation

Stability and special tests as directed by the differential:

- If you suspect lumbosacral radiculopathy, perform the straight leg raise

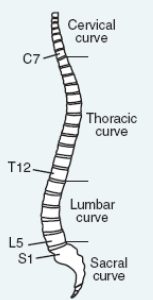

Key landmarks & structures:

Start by identifying each of the following structures, which will guide you as you perform the exam and document your findings.

-

- L1 vertebra. Count down from T7 (at the inferior pole of the scapula) or count up from L4 at the level of iliac crest

- L4 vertebra. At the level of the iliac crests

- L5 vertebra. Just above the gluteal cleft.

- Sacroiliac joints are located to either side of L4-L5

- Posterior superior iliac spine

- C7 is the prominent “bump” in the lower neck

Inspection

- Curvature of the spine.

- From behind, any lateral curvature of the spine is abnormal and suggests scoliosis.

- From the side, you should expect to see typical lumbar lordosis

- Muscle bulk should be symmetric side to side.

- Swelling, erythema or ecchymosis suggests trauma or infection.

- Asymmetry of hip or shoulder height suggests scoliosis or leg length differences.

Palpation

Palpate the low back, carefully noting any structures that are tender or asymmetric.

- Vertebrae from L1 to the sacrum

- Paravertebral muscles bilaterally

- Sacroiliac joints

Range of Motion

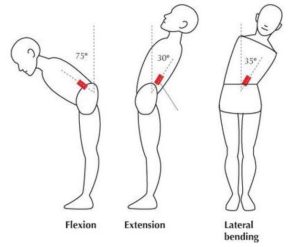

Test range of motion in 4 directions. Normal range of motion for the lumbar spine is:

Test range of motion in 4 directions. Normal range of motion for the lumbar spine is:

- Flexion: 60 to 90 degrees

- Extension: 25 to 30 degrees

- Lateral rotation (twisting): 25 degrees

- Lateral bending: 25 to 35 degrees

Neurovascular testing

Patients with non-specific back pain should have a normal lower extremity neurologic exam. Weakness, numbness or reflex changes are red flags for involvement of nerve root(s) or spinal cord. Additional red flag symptoms that may suggest something more serious going on in the back include: history of cancer or osteoporosis, fevers or chills, loss of control of bowel or bladder function (incontinence or inability to urinate or defecate)

Strength: assess lower extremity strength by testing each muscle group in isolation or with functional tests like squatting, standing, and heel and toe walking.

Sensation: To screen, test sensation at several points on each leg. If you are concerned about involvement of a specific nerve root, test sensation in that dermatome (see below).

Reflexes: Test the patellar, Achilles, and plantar reflexes. Increased or decreased reflexes suggest different causes of back pain.

- Compression of nerve roots causes a lower motor neuron injury and decreased reflexes.

- Compression of the spinal cord causes an upper motor neuron injury and increased reflexes. Upper motor neuron injury also causes an upgoing toe on testing of plantar reflexes (positive Babinski).

Hypothesis Driven Physical Exam

If you are concerned about a lumbosacral radiculopathy

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is a common cause of back pain, usually radiating down one leg. It’s caused by impingement of a nerve root by a herniated intervertebral disc or an osteophyte. The most commonly involved nerve root is L5, followed by S1 and L4. Findings specific to disc herniation at each level are:

| Pain | Numbness | Weakness | Decreased Reflex | |

| L4 | Back to medial thigh, medial ankle and foot | Medial calf and ankle | Quadriceps, tibialis anterior | Patellar |

| L5 | Back to back of leg, lateral calf, and classically, big toe | Dorsum of foot and big toe | Big toe extension, foot dorsiflexion, thigh abductors | No reflex associated with L5 |

| S1 | Back to back of leg, lateral ankle and sole | Lateral ankle and bottom of foot | Plantar flexion and thigh extension | Achilles |

To efficiently assess for findings of lumbar radiculopathy, test each of the following with the patient seated:

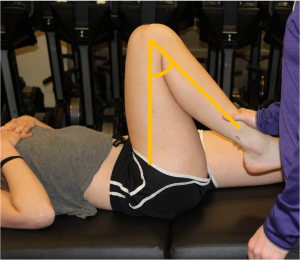

Straight leg raise (SLR)

With the patient supine, the examiner lifts the leg with the knee straight. If a bulging disc or osteophyte complex is present, this maneuver will stretch the L5 and S1 nerve roots over it, reproducing pain that radiates down the leg (not just to the back or hip).

The SLR is positive if it reproduces pain in the lifted leg at < 70 degrees of hip flexion. This finding has a high sensitivity but a low specificity. If the SLR is negative, it argues strongly against lumbosacral radiculopathy.

Term 2: Hip Exam

Inspect:

- Anterior, lateral and posterior hip

- Observe for antalgia and functional range of motion while walking.

Palpate: systematically from anterior to lateral to posterior, noting warmth, deformity, swelling, tenderness

Range of motion:

- Flexion and extension

- Adduction and abduction

- Internal rotation and external rotation

Strength:

- With the patient supine test extension, flexion, adduction

- With the patient in the lateral decubitus position test abduction, IR, ER

Stability and special tests as directed by DDx:

- FABER test

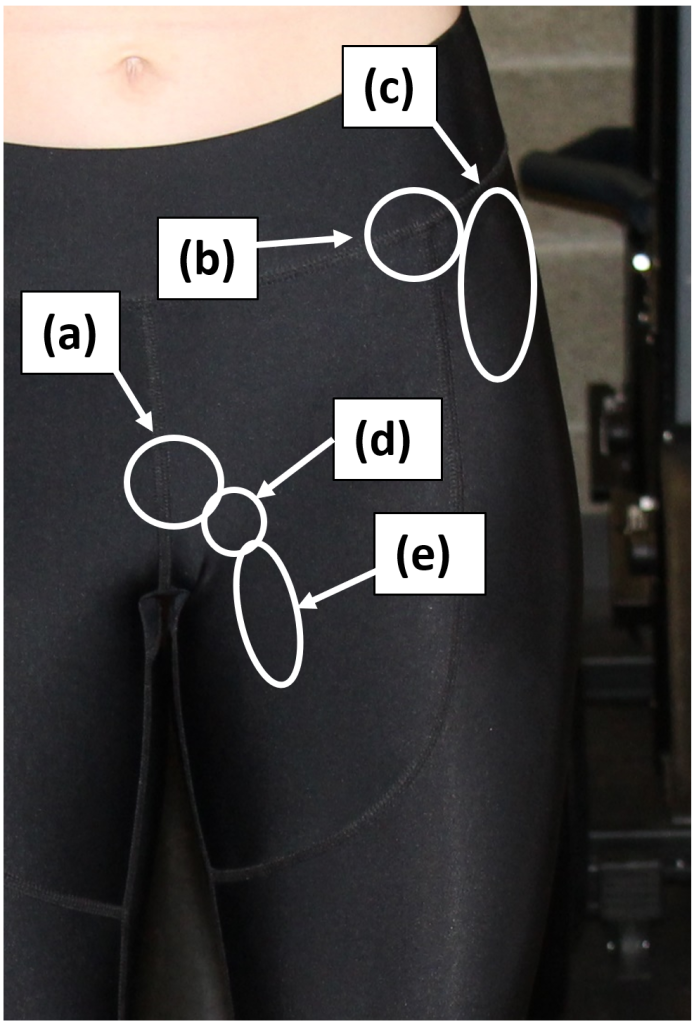

Key Landmarks & structures

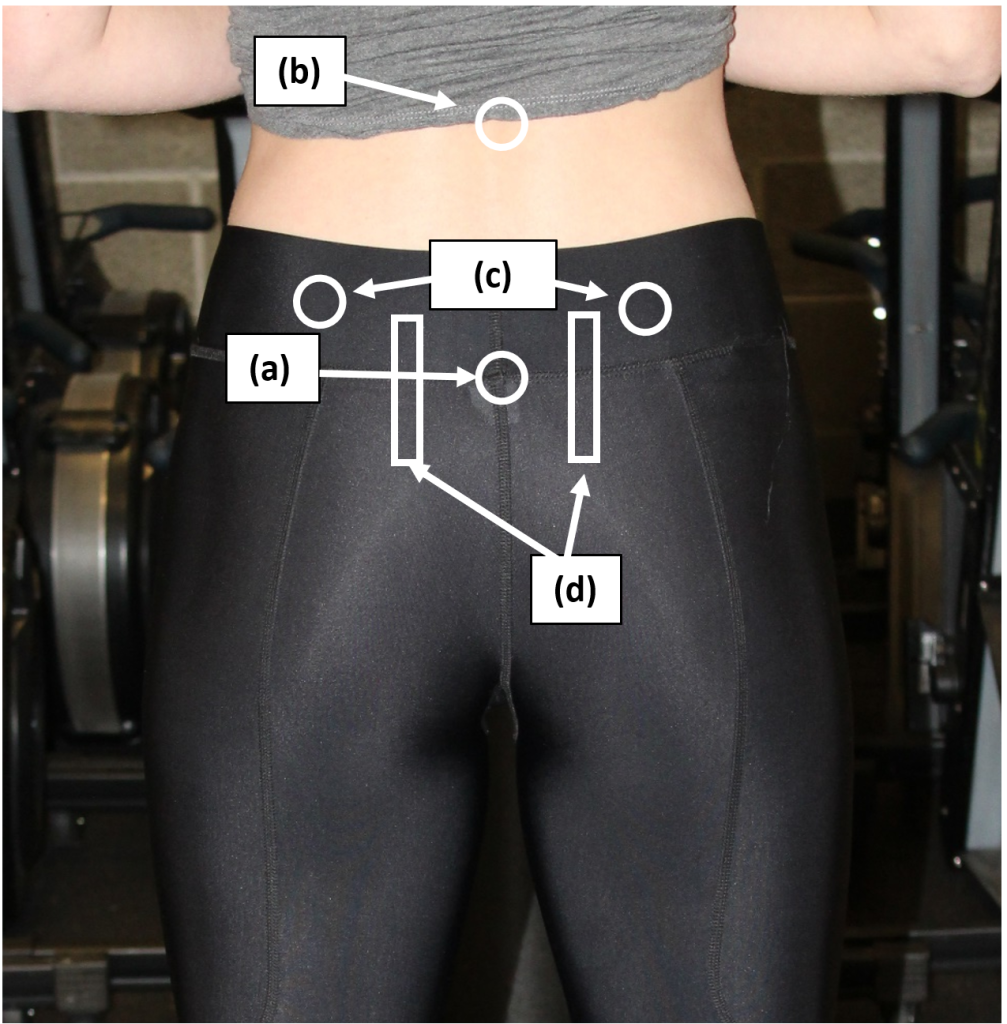

Identify each of the anatomic landmarks.

Inspection

Standing inspection should be performed for the anterior, lateral and posterior hip, noting swelling, erythema, ecchymoses, alignment and muscle bulk. Then, have the patient walk, observing for antalgia and functional range of motion.

Palpation

Palpate systematically, from the anterior to the lateral to the posterior structures of the hip above, noting any tenderness

Range of motion

Evaluate active and passive ROM. Normal ROM of the hip:

- Flexion (knee extended): 80-90 degrees

- Flexion (knee flexed): 110-120 degrees

- Extension: 10-20 degrees

- Adduction: 20-30 degrees

- Abduction: 30-50 degrees

- Internal rotation: 20-30 degrees

- External rotation: 40-50 degrees

Strength testing.

With the patient supine test:

- Extension

- Flexion

- Adduction

With the patient in the lateral decubitus position test:

- Abduction

- Internal rotation

- External rotation

Stability and special tests

FABER is an acronym for Flexion, Abduction, External Rotation and tests for pathology of the ipsilateral hip and contralateral SI joint. The patient flexes the leg at the hip and knee and abducts and externally rotates the hip. The examiner applies additional pressure to further externally rotate.

Term 2: Knee Benchmarks

Inspection

- Inspect the knees in the standing position, observing alignment and leg length

- Observe gait

- Inspect the knees in the seated or supine position, observing for deformity, swelling, erythema, and ecchymoses

Palpation

- Palpate systematically, noting warmth, deformity, swelling and tenderness:

- Patella, quadriceps tendon and prepatellar bursa

- Proximal tibia

- Proximal fibula

- Medial & lateral femoral epicondyles

- Popliteal fossa

- Medial and lateral joint lines

Range of motion

- Extension

- Flexion

Strength testing

- Knee extension

- Knee flexion

Stability and special tests:

- Test medial and lateral collateral ligament (MCL and LCL) stability with varus and valgus stress

- Test anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) stability with

- Anterior drawer test OR

- Lachman Test

- Test posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) stability with posterior drawer test

- Test for meniscal injury with McMurray’s test

- Evaluate for knee effusion if indicated by history and exam.

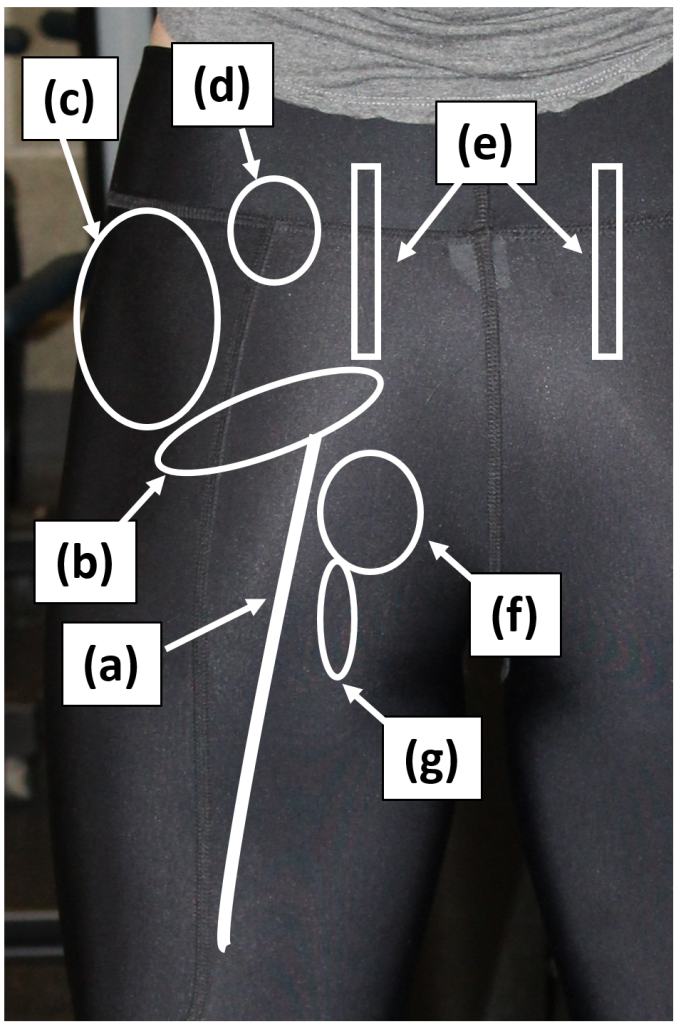

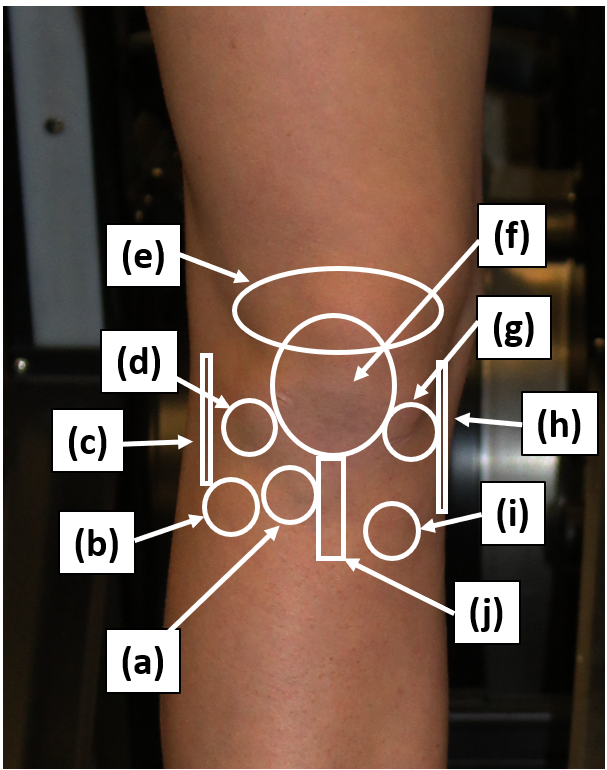

Key landmarks & structures

Identify each of the following anatomic landmarks, which will guide your exam and your documentation.

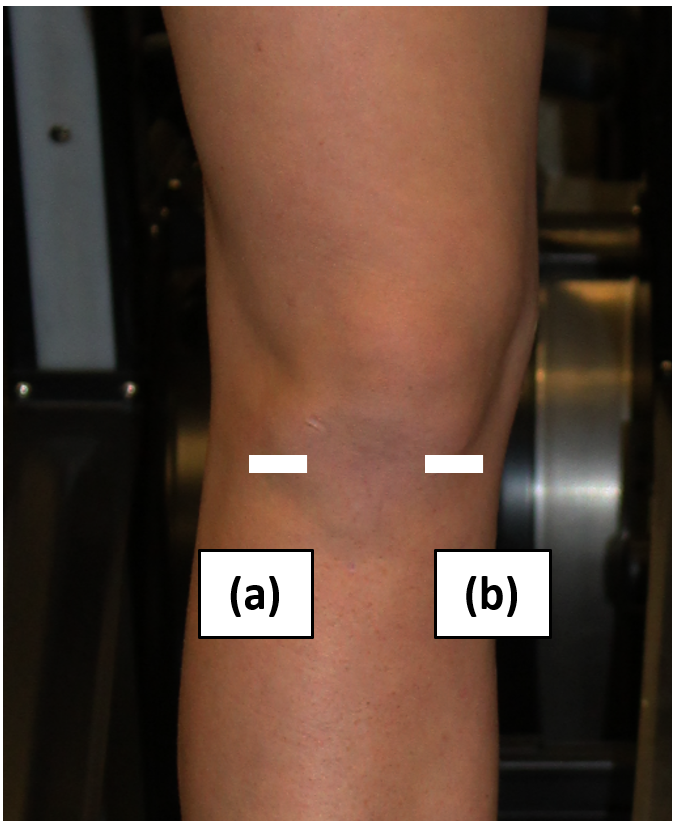

Inspection

Inspect the knees in the standing position, first anteriorly and then posteriorly, observing leg length and alignment. Next inspect the knees in the seated or supine position, observing for asymmetry, redness, swelling, bruising or deformity.

Differences in alignment may be described as:

- Varus or genu varum (historically referred to as “bow legs”)

- Valgus or genu valgum (historically referred to as “knock knees”)

|

|

|

Palpation

Systematically palpate the structures of the knee, comparing one side to the other. Carefully note any warmth, deformity, swelling or tenderness and attempt to identify any structures that are tender.

- Patella, quadriceps tendon and prepatellar bursa

- Proximal tibia (including tibial plateau area, patellar tendon, tibial tuberosity and Gerdy’s tubercle)

- Proximal fibula (including head and neck)

- Medial & lateral femoral epicondyles

- Popliteal fossa

- Joint Line: medial & lateral

Range of Motion

Evaluate active and passive range of motion, comparing the affected to the unaffected knee. If range of motion is limited note the following:

- Is motion limited by pain or “true” restriction?

- Is the end point “soft” or “firm”?

|

|

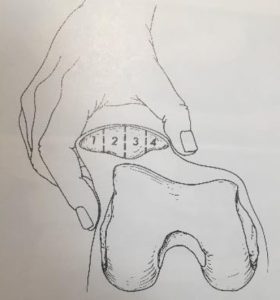

Motion of the patellofemoral joint should also be assessed. This is done passively primarily through medial and lateral motion of the patella.

Make not of the following:

- Amount of motion (see quadrants in image), including restriction of motion. 1-2 quadrants is considered normal.

- Pain

- Apprehension sign (sign of prior dislocation/subluxation of the patella)

Strength testing

With the patient in the seated position, test knee extension and flexion.

Strength testing can also help differentiate some causes of knee pain.

- Hip flexion can help to distinguish between quadriceps muscles that may be causing pain. Only the rectus femoris crosses both the knee and the hip – pain with hip flexion suggests that it may be causing knee pain.

- Hip adduction can bring out pain localized to the pes anserine.

- The Squat Test, where you ask patients to squat with the goal of reaching the “gluts to the floor,” tests flexion of the knee as well as pain with compression of the intra-articular structures such as the meniscus.

Hypothesis Driven Physical Exam

Ligamentous injuries

Most ligamentous injuries of the knee will be related to a traumatic event. They most frequently occur in athletes especially those involved in sports that require sudden changes in direction and speed. Injuries involving the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are the most common. Patients may complain of hearing a “pop” at the time of injury, swelling, locking (especially if the meniscus is also injured), giving out of the joint or a sense of knee instability.

- MCL injuries occur when knee is struck from the outside (valgus stress)

- LCL injuries occur when knee is struck from the inside (varus stress)

- ACL injuries can occur from a direct blow causing hyperextension or valgus deformation of the knee or from jumping or changing direction and causing rotation and lateral bending (valgus stress) to the knee.

- PCL injuries are the least common isolated ligament injury. Usually due to high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle accident with posteriorly directed force applied to flexed knee “dashboard injury.” Can also occur in low-energy trauma with direct blow to anterior knee or falling on flexed knee with foot plantar flexed.

- “Terrible triad” involves injury to MCL, ACL and the medial meniscus.

MCL and LCL stability testing

With your patient supine, apply varus and valgus stress to the knee at 0° and 30° of flexion, noting any laxity or pain. Pain may suggest a ligamentous strain. Laxity may suggest a tear of the ligament.

ACL and PCL stability testing

Next assess the stability of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. The two most commonly used tests for the ACL are the anterior drawer and Lachmann’s test. For the PCL, perform the posterior drawer. For each, note the amount of laxity and the presence or absence of a clear ‘endpoint’.

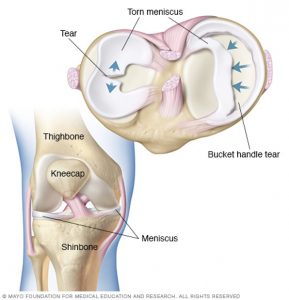

Meniscal injuries

Meniscal injuries are common. Acute meniscal tears usually occur from twisting injuries. Chronic degenerative tears can occur in older individuals with minimal twisting or stress. Meniscal injuries can occur in isolation or in association with collateral or cruciate ligament injuries/tears. Depending on the severity of the injury patients may present differently. Common complaints may include swelling, pain with twisting or pivoting, a sensation of popping, locking (inability to extend the knee fully), catching or the knee “giving out.”

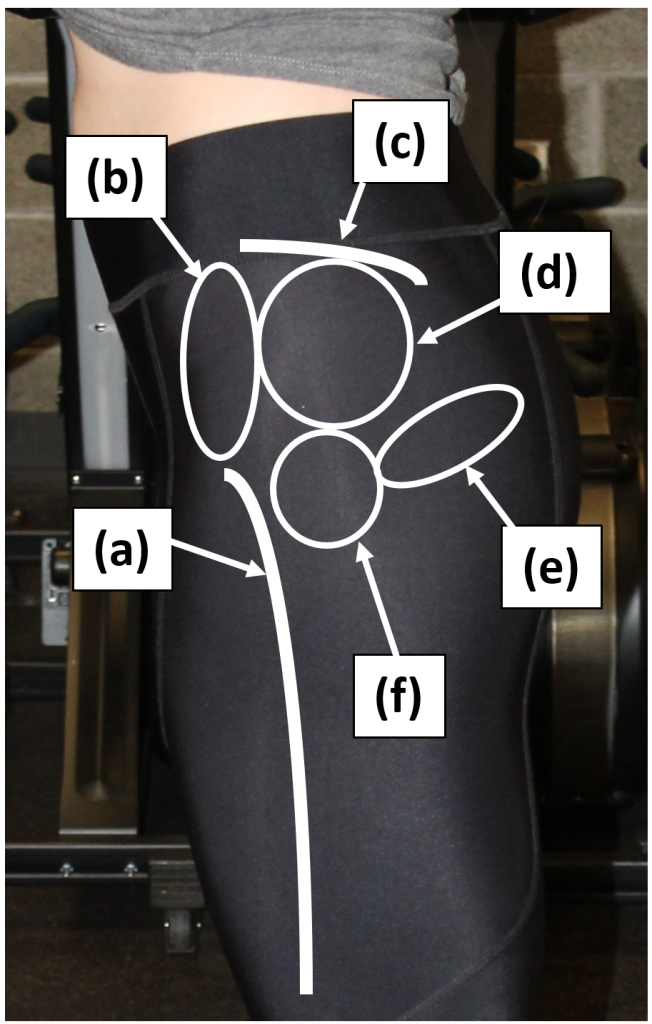

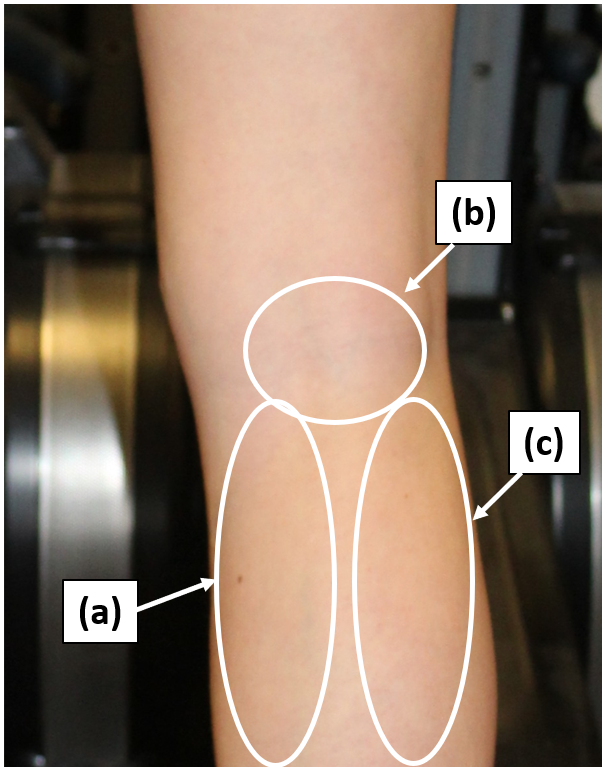

McMurray’s test

This is a fundamental component of the knee exam, performed to evaluate for tears of the medial and lateral meniscus.

This is a fundamental component of the knee exam, performed to evaluate for tears of the medial and lateral meniscus.

-

Examiner holds foot in one arm/hand. The other hand wraps over anterior knee with thumb and pointer/middle finger over joint lines.

-

Knee is then run through flexion and extension with internal and external rotation of the tibia

-

Positive test is indicated by a palpable clunk. Also note pain as this may indicate a non-displaced meniscal tear

-

Pain and clicking in the patellofemoral joint are common and important to distinguish from the medial and lateral joint lines

|

|

|

Assessment for joint effusions

There are many ways to assess for an effusion in the knee joint. One method is:

- Position the patient supine, with the knee extended.

- Place the thumb and finger of one hand on both sides of the patella.

- With the other hand compress the suprapatellar pouch against the femur, pushing fluid downwards if it is present.

- Feel for fluid with your thumb and finger

Term 2: Ankle and Foot Exam

Although this exam isn’t an FCM benchmark, foot and ankle concerns are common in primary care and emergency departments. As with any musculoskeletal exam remember the approach of inspection, palpation, range of motion, strength testing and special maneuvers.

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.

Key landmarks & structures

Inspection

Inspect the foot and ankle, observing carefully for swelling, erythma or ecchymosis. Also note:

- Alignment

- Muscle bulk

- Arch structure

- Appearance of first MTP joint

Palpation

Palpate the above structures systematically, noting any tenderness or swelling.

Range of motion

Tibiotalar Joint:

- Plantarflexion: 0 to -10 degrees

- Dorsiflexion: 30 to 40 degrees

Subtalar Joint

- Inversion: 30 degrees

- Eversion: 20 degrees

First MTP joint

- Flexion: 45 degrees

- Extension: 70 degrees

Strength testing

With the patient seated test:

- Plantar flexion of ankle

- Dorsiflexion of ankle

- Inversion of ankle

- Eversion of ankle

Stability and special tests

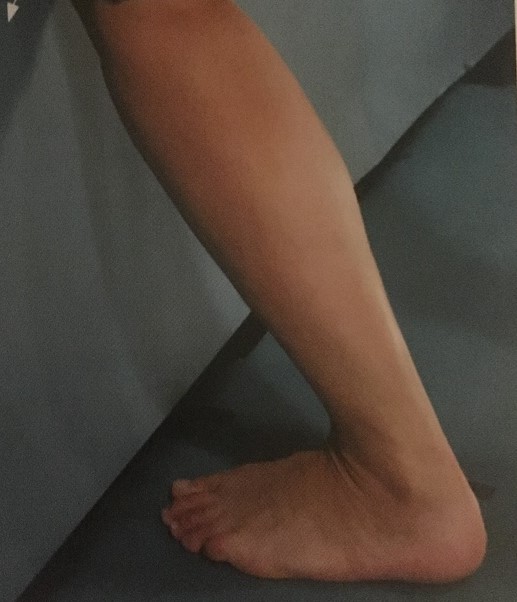

Thompson squeeze test

– Tests for the integrity of the Achilles tendon

– Pictures and drawing show two different versions of test

– The foot should rest in slight plantarflexion

– Compare to contralateral side

– Squeeze the gastroc muscles and foot should plantarflex

– Lack of plantarflexion with squeeze suggests Achilles tear

|

|

Anterior drawer test

Tests for stability of the ATFL

– One hand placed on tibia, held for stability.

– Opposite hand grips heel and distracts distally

– Note should be made of laxity and presence of clear end point

Lunge test

– Stresses tibiotalar joint and support structures

– Foot/heel kept on the floor

– Knee pushed forward to create dorsiflexion of the ankle

– Note should be made of pain and restricted motion

MSK Workshop 2. Knowledge Check