Cardiovascular Exam

Benchmark exam you should be able to demonstrate on completion of FCM:

Inspection

- Inspect the anterior chest and neck for skin lesions as you perform the exam

- Inspect the precordium for abnormal movement

Palpation

- Palpate the carotid arteries, one at a time, observing strength & symmetry (may also be done with H&N exam)

- Palpate the apical impulse and interpret your findings

Auscultation

- Listen at each of the primary listening areas with firm pressure on the diaphragm:

- Right 2nd intercostal space (R upper sternal border)

- Left 2nd intercostal space (L upper sternal border)

- Left lower sternal border (along the sternum at the 5th intercostal space)

- Cardiac apex (midclavicular line in the 4th – 5th intercostal space)

- Listen light pressure on the diaphragm or with the bell at the cardiac apex

- Listen for bruits over each carotid artery

Peripheral Circulation & Edema

Palpate each of the following pulses on each side:

- Radial

- Femoral

- Dorsalis pedis

- Posterior tibialis

Note the presence and severity of leg edema

Perform hypothesis driven exam maneuvers:

- If you suspect abnormal volume status, measure jugular venous pressure

- If you suspect ventricular hypertrophy or valvular heart disease, assess the apical impulse

Use headphones or earbuds to listen to the heart sounds in this chapter.

Immersion: Landmarks & Structures

Identify each of the following structures on yourself or on your physical exam partner.

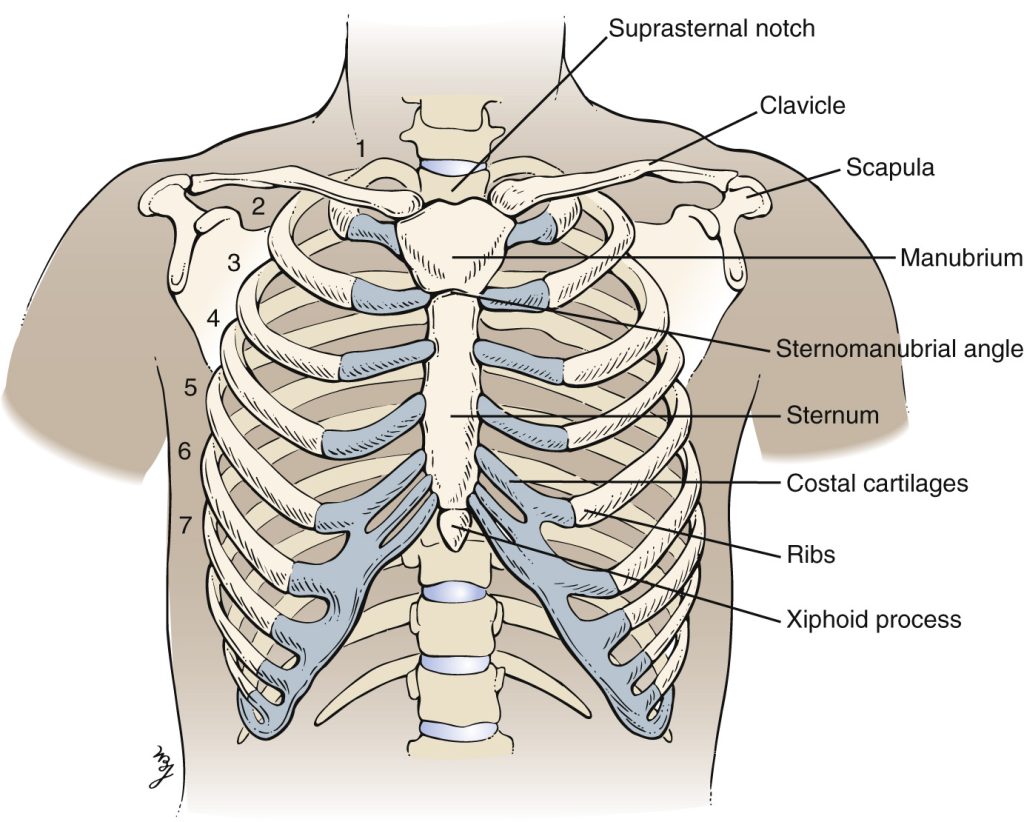

Suprasternal notch. Depression at the base of the neck, formed by the medial ends of the clavicles and top of the manubrium.

Sternomanubrial angle (a.k.a sternal angle) From the suprasternal notch, palpate down the sternum to find the place where the angle changes.

Midclavicular line (MCL). The line that runs through the midpoint of the clavicle towards the feet.

Four classic areas for auscultation:

- Right 2nd intercostal space. often referred to as R upper sternal border (RUSB). The space between ribs to the right of the sternomanubrial angle. Sounds from the aortic valve are often best heard here.

- Left 2nd intercostal space, often referred to as L upper sternal border (LUSB). The space between ribs to the left of the sternomanubrial angle.Sounds from the pulmonic valve are often best heard here.

- Left lower sternal border, in the area of the 5th left intercostal space. Palpate the 3rd, 4th and if possible the 5th left ICS. Sounds from the tricuspid valve are often best heard here.

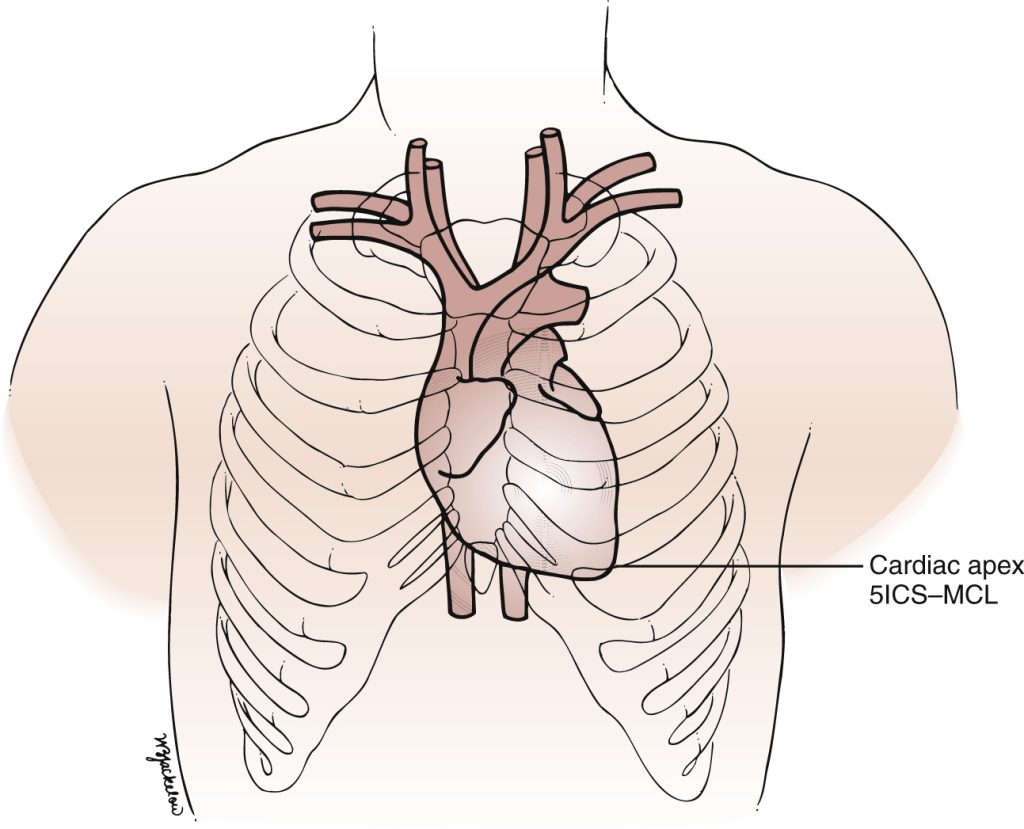

- Cardiac apex, the tapered tip of the left ventricle, which should lie at or medial to the MCL in the L 4th or 5th intercostal space. Sounds from the mitral valve and extra heart sounds are often best heard here, and on some people, the apical impulse can be palpated

Image from Chapter 13 of Textbook of Physical Diagnosis: History and Examination, Eighth Edition, Copyright © 2021. See link at the end of this chapter.

Image from Chapter 13 of Textbook of Physical Diagnosis: History and Examination, Eighth Edition, Copyright © 2021. See link at the end of this chapter.

Immersion: Exam Steps

Draping and modesty

Use appropriate draping to preserve patient comfort, adjusting as needed to maintain coverage. Avoid making assumptions that male patients are comfortable baring the torso. Ask permission or ask your patient to move their gown as needed, lowering from the neckline and/or raising from below to complete the exam appropriate for your individual patient. It is often easiest to inspect the precordium, palpate the apical impulse, and auscultate at apex with the gown raised from below. It can be lowered at the neckline to listen at the sternal borders.

For a complete cardiac exam in the hospital, start with your patient positioned at about a 30° angle, with the examiner ideally on the right. In the primary care clinic, many exams are performed with the patient sitting up on the exam table, which will detect abnormal cardiac rhythms like atrial fibrillation and some murmurs. The supine and partial left lateral decubitus position will allow you to better detect most abnormal sounds.

Inspection

Inspect the skin of the precordium as you perform the exam. Note any movement of the chest. In healthy people, the beating of the heart doesn’t usually cause any visible movement. In people with enlargement of one or more chambers of the heart, abnormal movement may be seen or more commonly felt.

Palpation

If you are concerned about valvular disease or cardiomyopathy, palpate the anterior chest for the apical impulse. In Immersion, if your PE partner is comfortable with this, you can also palpate it to identify the optimal location for auscultation.

Palpate to the L of the sternum, at the MCL in the 4th or 5th ICS. Palpate medially and then laterally if you are unable to find it initially. You may be able to palpate the apical impulse over breast tissue, or you may need to ask your patient to lift the breast to allow palpation.

The normal apical impulse is:

- palpable in < 50% of normal adults in the supine position

- less than the size of a quarter, or 2 cm in diameter

- at or medial to the mid-clavicular line in the 4th or 5th intercostal space

Healthy people with thin chests or high cardiac output states, like fever or pregnancy, can also have palpable movement just to the L of the lower sternum. Obvious or sustained movement in this area is caused by pressure overload of the right ventricle, which lies underneath and to the left of the sternum, or by an enlarged, overloaded left atrium.

Auscultation

Listen to the heart in a quiet room with a quiet patient. Listen at each of the four primary listening areas with the diaphragm of the stethoscope applied firmly to the chest. At each location, listen for normal heart sounds as well as extra heart sounds like murmurs or gallops. Then listen again at the cardiac apex with the bell or with the diaphragm of a tunable stethoscope applied lightly to the chest. If your patient has breasts, you may be able to hear heart sounds at the apex through breast tissue or you may need to ask them to lift the breast.

Use headphones to “auscultate” the normal heart sounds below. At each listening area, you should hear the “lub dub” of the normal cardiac cycle. Closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves, which connect the atria to the ventricles, creates the first of each pair of heart sounds, S1. Closure of the aortic and pulmonic valves, which connect the ventricles and the great arteries, creates the second heart sound, S2.

Systole is the period between S1 and S2, and diastole is the period between S2 and the following S1, when blood from the atria is filling the ventricles. Differentiating the two will become automatic with experience. For now, use the following clues to help you recognize systole and diastole:

- Systole is shorter than diastole at heart rates < 100

- S2 is almost always louder than S1 at the RUSB

- The beat of the carotid pulse happens during systole

Immersion: Sample documentation

Apical impulse is < 2 cm at L midclavicular line in the 5th intercostal space

Regular rate and rhythm. Normal S1 and S2, no S3, S4, or murmurs

Pulses 2+ and symmetric: carotid, radial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibialis***

No edema in the bilateral lower extremities***

*** Note: Palpation of carotid pulses may be performed in the head and neck exam. Palpation of dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis pulses and for edema is usually performed with the lower extremity exam.

Immersion: Exam Video

Immersion: Knowledge Check

Term 2: Hypothesis driven maneuvers

Measure jugular venous pressure

If you suspect abnormal volume status, assess jugular venous pressure. This is demonstrated in the video below and in the workshop.

- Position the head of the bed at 30°-45°. Your patient should be resting comfortably against the bed with the neck relaxed and turned slightly away.

- Identify internal jugular venous pulsations or the conduit of the external jugular vein. If you cannot see them, adjust the head of the bed. Move it up if you suspect volume overload and down if you suspect volume depletion.

- Locate the top of the neck veins, defined as the point where the internal jugular venous pulsations become imperceptible or the conduit of the external jugular disappears

- Measure the vertical distance between the top of the neck veins and the sternal angle.

- Add this distance to 5 cm.

Clinical significance:

- The normal JVP is 5-8 cm of H2O

- Elevated JVP argues strongly that the directly measured central venous pressure (=right atrial pressure) is over 8 cm H2O. The elevated central venous pressure could be caused by left heart disease, primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension, or pulmonic stenosis.

- Flat neck veins with your patient supine correlates with a measured CVP less than 5 cm of H2O, suggesting intravascular volume depletion.

Assess apical impulse

If you suspect ventricular hypertrophy or valvular heart disease, palpate the apical impulse.

The normal apical impulse in the 4th or 5th intercostal space, at or medial to the midclavicular line. It should be a quick tap, about the size of a dime, against the examiner’s hand as the left ventricle contracts. It is palpable in only a third of healthy adults and is more likely to be felt it in the partial left lateral decubitus position.

- A laterally displaced apical impulse is a specific but insensitive finding of ventricular enlargement and/or a depressed ejection fraction. If your hypothesis is that these are present, the finding of lateral displacement of the apical impulse supports it. Given the low sensitivity, the absence of lateral displacement doesn’t argue strongly against it.

- An enlarged apical impulse is defined as > 4 cm in the partial left lateral decubitus position and also supports a hypothesis of enlargement of the ventricle.

- A sustained apical impulse lasts longer than normal and indicates pressure or volume overload of the left ventricle.

Term 2: Abnormal findings

Murmurs

Identifying murmurs is a skill that you will begin to build in Foundations. The recordings and additional resources in this chapter are a good place to start. A good next step is careful auscultation of a patient’s murmurs with comparison to what your preceptor or an echocardiogram found.

Five characteristics of a murmurs are used to identify its cause and determine the need for an echocardiogram. You should assess and report:

- Grade: from I-VI

- Quality, for example harsh or blowing

- Timing in systole or diastole

- Location where the murmur is heard

- Radiation to other sites such as the carotids or axilla

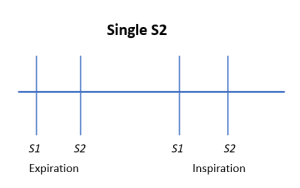

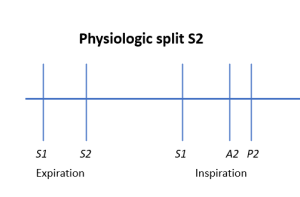

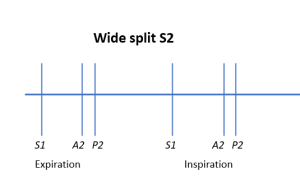

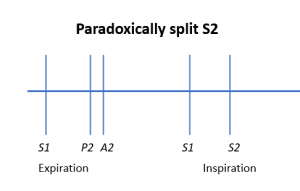

Normal and Abnormal S2 splitting

The second heart sound is composed of A2 (aortic valve closure) and P2 (pulmonic valve closure). In healthy people, A2 and P2 are nearly simultaneous during expiration and are heard as a single sound. In inspiration, the negative intrathoracic pressure that pulls air into the chest also increases venous return to the right ventricle. Because more time is needed for this extra blood to cross the pulmonic valve, P2 is delayed. In some healthy people, it may be heard as a separate sound at the LUSB. This is called normal physiologic splitting.

Wide splitting means that A2 and P2 are both audible throughout the respiratory cycle. In atrial septal defect, a L to R shunt increases blood flow across the pulmonic valve during both expiration and inspiration. Because there is no variation with the respiratory cycle in ASD, splitting is both wide and ‘fixed’, or consistent.

Right bundle branch block is a more common cause of wide splitting. Although it can be hard to hear, there is still respiratory variation in RBBB so splitting is wide but NOT fixed.

Paradoxical splitting is heard during expiration rather than inspiration. In this case, A2 is delayed and follows P2. Inspiration increases venous return so P2 “catches up” creating a single S2. Left bundle branch block, advanced aortic stenosis and CHF can all cause paradoxical splitting.

S3 and S4

S3 and S4 are low frequency extra sounds best heard with the bell of the stethoscope at the cardiac apex. If you suspect but don’t hear these sounds, re-examine the patient in the left lateral decubitus position.

| S3. “I be-lieve.” |

|

Sudden deceleration of blood flow into the L ventricle in early diastole. | Adults: CHF, valvular disease

Children: may be normal |

| S4. “Be-lieve me.” |

|

Atrial contraction pushing blood into a stiff ventricle in late diastole. | Hypertrophy or fibrosis |

S3 occurs during early diastole and is caused by sudden deceleration of blood flowing rapidly into the left ventricle . In patients over 40, the cause is almost always systolic heart failure or valvular regurgitation. If the L atrium is overfilled, as in mitral regurgitation, high pressure will increase early diastolic filling. If the left ventricle is non-compliant or overfilled, as in heart failure, early diastolic blood flow will decelerate quickly. Both situations can cause an S3.

An S3 may be a normal finding in children and young adults. Their healthy ventricles relax in early diastole to allow very rapid filling, which can cause an S3 even with a normal ventricle.

S4 is heard in late diastole, when atrial contraction pushes blood into the ventricle, and indicates the ventricle is abnormally stiff, due to hypertrophy or fibrosis.

Pericardial rub

A pericardial rub is a high-pitched, scratchy sound caused by pericardial inflammation. A rub is best heard along the lower left sternal border using the diaphragm of the stethoscope with the patient sitting up, leaning forward, and briefly holding the breath.

Edema

The most common causes of bilateral edema are venous stasis disease, congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, drug induced edema, and liver or kidney disease. The most common causes of unilateral edema are deep vein thrombosis, Baker’s cyst and cellulitis.

Assess for pitting edema by pressing on the distal tibia for 2 seconds. If a depression (“pit”) remains, pitting edema is present. Pitting indicates that edema fluid is low protein, as in congestive heart failure, hypoalbuminemia, or pulmonary hypertension. Repeat as needed to define the proximal extent of the edema.

Edema is often graded on a subjective 1-4 scale. Severity can also be documented by describing the proximal extent as well as the presence or absence of weeping or skin ulceration.

Absent peripheral pulses

Peripheral pulses should be assessed if you suspect cardiovascular disease.

- Femoral pulses are palpated just below the inguinal ligament, midway between the pubic tubercle and and the anterior superior iliac spine

- Posterior tibialis pulses are palpated just behind the medical malleolus

- Dorsalis pedis pulses are palpated on the mid-dorsum of the foot, just lateral to the extensor tendon of the big toe.

Many healthy people lack either the posterior tibialis or the dorsalis pedis pulse, but if one is anatomically absent the other is enlarges to make up the difference. The absence of both pedal pulses supports a diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease.

Term 2: Advanced CV Knowledge Check

Either before or after the workshop, please complete these 10 AMBOSS questions on the cardiac exam. There are typically several questions about the CV exam on Step 1, many with audio.

https://next.amboss.com/us/shared/questions/HUJwKetPd/1

Resources & references

University of Michigan Professional Skills Builder. Heart Sounds & Murmurs library. The murmur examples in this chapter come from this collection, which is open access. Check it out if you’d like to hear more.

Access Medicine Multimedia: Auscultation Classroom. Examples of common and uncommon murmurs.

Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis, 5th edition. McGee SR. The definitive summary of the evidence for different physical exam maneuvers by a now retired University of Washington Professor of Internal Medicine. Full text is available via Clinical Key on the Health Sciences Library Care Provider Toolkit.

- Inspection of the Neck Veins

- Palpation of the Heart

- Auscultation of the Heart: General Principles

- The First and Second Heart Sounds

- The Third and Fourth Heart Sounds

- Heart Murmurs: General Principles

left anterior chest

narrowing or leaking of one of the 4 heart valves

abnormal function of the heart muscle

patient rolled 45 degrees to the left, to bring the apex of the heart closest to the chest wall.

I = faint. II = easily heard. III = loud. IV = thrill and heard with stethoscope on chest. V = thrill and heard with stethoscope edge on chest, VI = thrill and heard with stethoscope off chest