Across the Lifecycle

Although the basic elements of the H&P are similar across the lifecycle, interview strategies, information gathered, preventive health measures and common health concerns differ substantially. In this workshop, you’ll learn to adapt the history and physical exam for children, adolescents, and older adults, learning key skills and strategies that you can practice in your primary care clinic. In the Lifecycle block at the end of Foundations, you will learn more about normal childhood, adolescent development, aging and geriatric care.

Adapting the encounter: Children

Children see the doctor for the same reasons as adults: acute problems, chronic conditions, and preventive or ‘well child’ visits, which are much more frequent for kids than adults. In this workshop, you’ll learn how to adapt the interview and exam for the children you may see in your primary care practicum..

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that WELL CHILD visits occur frequently for the first year of life. The frequency gradually decreases to once a year after age 3. The well child visit is different than a problem based visit addressing a specific concern. You will learn more about pediatric health conditions in the Lifecycle Block and during your pediatric and family medicine clerkships. The content in this chapter is what should be considered and addressed at well child visits as it is considered preventative care. The goals of well child care are to:

- Address parental concerns

- Track growth and development

- Prevent disease and injury

- Identify and address common disorders early

- Promote healthy parenting with Anticipatory Guidance.

Pediatric Interview

Triadic interviews, which include a caregiver in addition to the patient and clinician, are the norm for pediatric visits. It can be tempting to direct most questions to the caregiver, but always try to include the child. This demonstrates respect, and gives them a sense that they’re part of the process, leading to greater trust and engagement.

At the start of the visit, establish rapport with both the patient and the caregiver. You want to make the child comfortable, but how you do it will vary with their age and personality – stay flexible and observe your preceptors for ideas. Let children check out your instruments or ask them about the characters on their clothes or the toys they brought. You can also engage in age appropriate play, like peek-a-boo for toddlers.

The information a child is able to provide depends on their age, developmental level and communication abilities. Another major variable is how shy they are. A parent may tell you that they speak in complete sentences at home, but you may not get anything out of them because you just met.

With infants and young toddlers, you’ll depend completely on the caregiver for history, which will be based on their observations. Parents can observe changes like fever, crying, weight change, vomiting or decreased appetite. Symptoms like pain, nausea, or fatigue can’t be observed. When parents tell you their infant is in pain, they are interpreting what they have seen – but they are usually right!

Sometime in the second year of life, kids start to develop single words and may be able to answer yes/no questions. By age 5-6, most children can participate in an interview, and should have initial questions asked directly of them. You’ll confirm the history with the parent, or at least look to them to see how they’re reacting – usually they’ll speak up if something doesn’t sound right.

| Age | Suggested interviewing techniques |

| Toddlers | Ask yes/no questions using kid friendly words |

| Preschoolers | Add more open-ended questions |

| By age 6-8 | Expect reliable information |

| By age 10 | Child is primary source of information |

| At age 11-12 | Part of visit will be done without the parent |

Birth history

Prenatal events, complications of delivery, and especially prematurity can impact children’s long term health. When seeing a new pediatric patient, ask about:

- Gestational age at birth – this is usually reported in weeks.

- Any problems during pregnancy

- Any exposures during pregnancy, to drugs, alcohol or medications

- Any problems in the newborn period

Developmental history

Healthy children develop motor, communication, and social-emotional skills at predictable times and in a predictable sequence as the nervous system matures and myelinates. Development is assessed at each well visit so that disorders such as autism can be identified and addressed as early as possible.

Parents are asked if they have any concerns and a structured tool is used to assess whether children are meeting expected milestones. The Survey of Wellbeing of Young Children and the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures are two commonly used tools. These tools discuss health promotion and prevention and give evidence based guidance for preventative care. You can also find information on universal screening recommendations. If any concerns are identified on this initial investigation, your preceptor may use more specific tools to assess for specific developmental problems. You’ll learn more about normal childhood development and developmental disorders in the Lifecycle block.

Developmental milestones are often presented in a table like the one below (you don’t need to memorize this!) The milestones in black text are met by 50% to 90% of children, while those in green text are met by over 90%. The absence of protodeclarative pointing at one year and of the ability to say one word at 15 months should trigger specific screening for autism. By utilizing these developmental milestones, autism, hearing or vision issues, speech or motor delay can be identified and addressed as early as possible. For a screen reader friendly version of this table, click here.

| AGE | GROSS MOTOR | FINE MOTOR | COGNITIVE COMMUNICATION | SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL |

| 2 months | Head up 45°

Lift head |

Follow past midline

Follow to midline |

Laugh

Vocalize |

Smile spontaneously

Smile responsively |

| 4 months | Roll over

Sit–head steady |

Follow to 180°

Grasp rattle |

Turn to rattling sound

Laugh |

Regard own hand |

| 6 months | Sit–no support

Roll over |

Look for dropped yarn

Reach |

Turn to voice

Turn to rattling sound |

Feed self

Work for toy (out of reach) |

| 9 months | Pull to stand

Stand holding on |

Take 2 cubes

Pass cube (transfer) |

Dada/Mama, nonspecific

Single syllables |

Wave bye-bye

Feed self |

| 1 year | Stand alone

Pull to stand |

Put block in cup

Bang 2 cubes together |

Imitate sounds

Babbling* 1 word |

Protodeclarative pointing*

Wave bye-bye Imitate activities Play pat-a-cake |

| 15 months | Walk backwards

Stoop and recover Walk well |

Scribble

Put block in cup |

1 word*

3 words |

Drink from cup

Wave bye-bye |

| 18 months | Walk up steps

Run Walk backwards |

Dump raisin

Tower of 2 cubes Scribble |

Point to 1+ body parts

6 words 3 words |

Remove garment

Help in house |

| 2 years | Throw ball overhead

Jump up Kick ball forward Walk up steps |

Tower of 6 cubes

Tower of 4 cubes |

Name 1 picture

Combine words Point to 2 pictures |

Put on clothing

Remove garment |

| 2.5 years | Throw ball overhead

Jump up |

Imitate vertical line

Tower of 8 cubes Tower of 6 cubes |

Know 2 actions

Speech half understandable Point to 6 body parts Name 1 picture |

Wash and dry hands

Put on clothing |

| 3 years | Balance on each foot

Broad jump Throw ball overhead |

Thumb wiggle

Imitate vertical line Tower of 8 cubes Tower of 6 cubes |

Speech all understandable

Name 1 color Know 2 adjectives Name 4 pictures |

Name friend

Brush teeth with help |

Knowledge check

At which age can 90% of children perform these tasks?

Social History

In children, the social history focuses on the family rather than the individual and is probably even more important than it is in adults Almost half of American children live in poverty or near poverty, and adverse childhood experiences, such as domestic violence, parental substance use, divorce and death all impact the long term health of children. The I-HELLP pediatric social history assesses child and family needs across five domains: Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Literacy and Personal safety. In a study of pediatric patients, the use of IHELLP tripled the number of referral to social workers, who were able to connect families with community and legal resources to help address these issues 78% of the time.

| Income | Suggested questions |

| General | Do you ever have trouble making ends meet? |

| Food income | Do you ever have a time when you don’t have enough food? Do you have WIC? Food stamps? |

| Housing | |

| Housing | Is your housing ever a problem for you? |

| Utilities | Do you ever have trouble paying your electric/heat/telephone bill? |

| Education | |

| Appropriate Education Placement | How is your child doing in school? Are they getting the help to learn what they need? |

| Early Childhood Program | Is your child in Head Start, preschool, or early childhood enrichment? |

| Legal Status | |

| Immigration | Do you have questions about your immigration status? Do you need help accessing benefits or services for your family? |

| Literacy | |

| Child Literacy | Do you read to your child every night? |

| Parent Literacy | How happy are you with how you read? |

| Personal Safety | |

| Domestic Violence | Have you ever taken out a restraining order? Do you feel safe in your relationship? |

| General Safety | Do you feel safe in your home? In your neighborhood? |

Immunization history

Immunizations should be reviewed at every visit (including both well child and problem based visits), with catch-ups offered if necessary. Most electronic health records allow providers to track immunizations and remind them of those that are due. The Centers for Disease Control offers a free up-to-date app for immunization schedules and information – download it from this link or look for CDC Vaccine Schedules on the App Store.

Immunizations are required for licensed childcare and school attendance by state law. The development of herd immunity helps to protect those who cannot receive certain vaccines. As doctors we can emphasize that the more patients that get vaccinated the healthier the community will be.

About one-third of parents are vaccine hesitant, meaning they have questions or concerns about having their child immunized. Most parents will still end up vaccinating despite these concerns, and information provided by a trusted physician can help. Communication strategies that can make a difference include:

- Present vaccination as the default option. A “presumptive” approach that assumes parents will immunize their child has been shown to be more effective than the participatory approach that we use for many other medical decisions. For example, “Jenna is due for hepatitis, rotavirus, and polio vaccines today” rather than “What do you think about vaccines today?”

- Listen to and acknowledge the parent’s concerns in a non-confrontational, non- judgmental, and respectful way.

- Address parent’s specific concerns with a mix of scientific information and personal stories, such as the choice you’ve made for your own children or recommended for family or friends.

- Be honest about adverse affects, providing accurate information along reassurance about the robustness of the vaccine safety system.

Because immunizations are such an important part of well child visits, please download the CDC Vaccine Schedules App. To familiarize yourself with the information available in the app, please find the answer to the following question.

Knowledge check

Pediatric Physical Exam

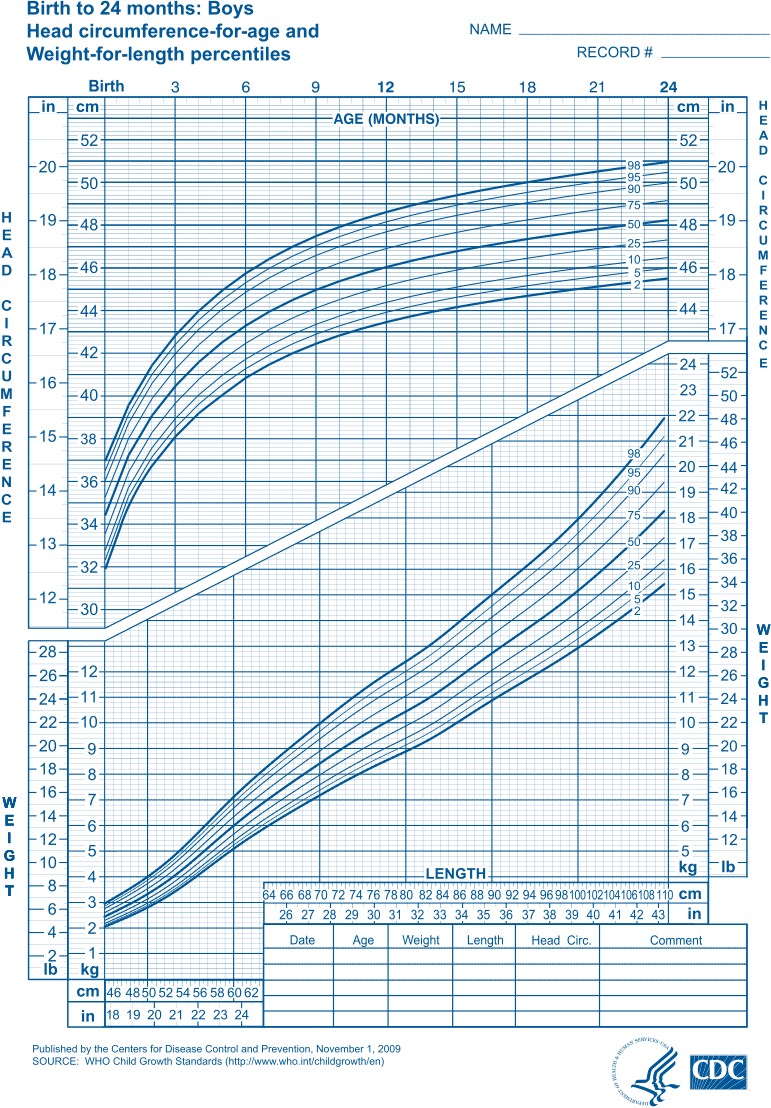

At each well visit, the child is weighed and measured and that data is plotted on a growth chart like the one below. The provider reviews and interprets the findings, paying particular attention to trends over time. Children who are growing normally tend to stay on the same percentile curve for weight, length, and head circumference. Crossing percentiles can be an early sign of abnormal growth that should be addressed. Growth should also be proportional – weight and height should generally increase at a similar rate. You’ll learn more about normal growth, failure to thrive, and how to address childhood obesity in a nonjudgmental way during your Lifecycle block.

Anticipatory guidance is the proactive counseling offered at well child visits for health promotion and injury prevention. It addresses common issues and concerns based on the age and developmental stage of the child, with special attention to the prevention of injuries, which are still the most common cause of death in children. For example: most infants learn to roll over at about 4 months, so anticipatory guidance at the two month visit includes keeping a hand on the child when they’re on a high surface like a changing table.

Most practices have standard handouts to give families at each well visit. Providers might highlight or discuss the recommendations of most interest or relevance to a family, and let them review the rest at home. Areas addressed include:

- Feeding, diet, and activity

- Dental care

- What to expect in terms of development

- Safety and injury prevention

- Screen time

Adapting the Encounter: Adolescents

Adolescence is a time of exploration, growth and often, risk-taking. An in depth psychosocial history, often framed as a HEADSSS assessment, can identify a teen’s strengths, stressors and potential threats to health. Confidentiality is a critical issue – research shows that teens will share more if physicians create the space for teens to speak privately with them.

Adolescent development

Like younger children, adolescents usually develop in a predictable way: physically, cognitively and psychosocially.

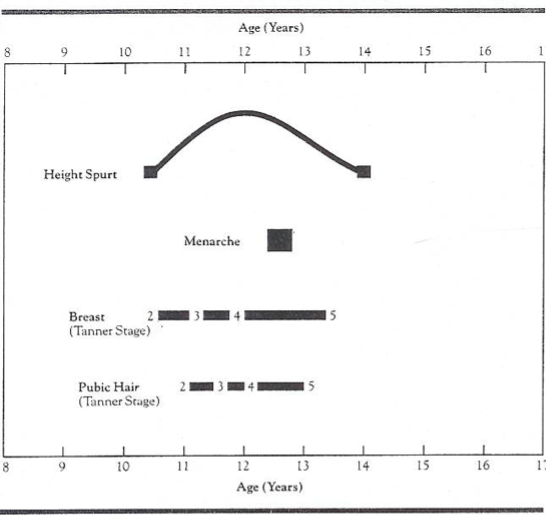

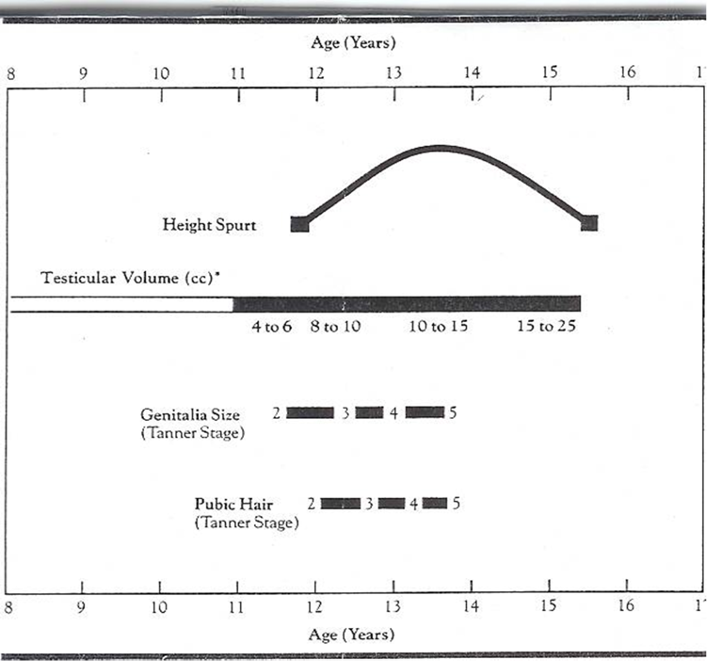

The physical changes of puberty reflect hormonal changes that you will study in depth in the Lifecycle block. The order of changes is similar for males and females, but the timing and rate of of puberty differs. In those assigned female at birth, the average onset of puberty is at age 9-10 and lasts 3-4 years. For those assigned male, puberty begins about a year later, and lasts 4-6 years. The onset of puberty varies across individuals, with a wide range considered normal.

Psychosocially and cognitively, adolescence is often divided into 3 stages, with advances at each stage as outlined below

- Early adolescence, from ages 10-13

- Middle adolescence, from ages 14-17

- Late adolescence, from ages 18-21

| Cognitive | Psychosocial | |

| Early | Retain concrete thinking Begin to question authority and societal standards Conformist morality of childhood Learning by trial and error Beginning of abstraction Imaginary audience, on stage all the time – others are thinking about them |

Begin to separate from parents and identify with peers

Confrontational with parents Preoccupation with self/privacy Preoccupation with being like peers Conformity Lack of impulse control |

| Middle | Thinking less childlike – more abstract, analytic, introspective

Begin to realize they are sexual beings Can analyze facts and make better choices, based on the consequences of their decisions Sensitive to criticism |

Peak conflict/peer/risk behavior Conformity with peer values Feeling of omnipotence and immortality Increasing independence Less idealistic vocational aspirations Questioning “who is the real me?” Behave differently with different people |

| Late | Conceptualize/verbalize thoughts Full adult reasoning/identity Ability for abstract thinking Understanding consequences of behavioral choices Increased thoughts about more concepts |

Integration of diverse views of self

Willingness to compromise Less importance placed on peer group Accepts parental values or develop own Realistic vocational goals |

Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR)

The Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR), also known as Tanner stages, is a scale used to monitor an adolescents physical development during puberty. The scale ranges from I (prepubertal) to V (adult).

Pubertal Events: Assigned Female

-

Breast buds appear (thelarche)

-

0-6 months later, pubic hair begins

-

Growth spurt begins soon after thelarche

-

Physiologic leukorrhea (odorless white vaginal discharge) begins 6-12 months prior to menarche

-

Menarche begins 2 1/2 years after breast buds (usually at SMR stage 4)

Pubertal Events: Assigned Male

-

Increase in testicular volume

-

6-8 months later the penis begins to grow & scrotal skin darkens

-

Pubic hair begins 6-18 months after testicular growth

-

Spermarache begins in SMR stage 3

-

Facial hair begins SMR stage 4+

Privacy and confidentiality

Beginning at age 11-12, most providers spend part of each well visit talking to an adolescent privately about sensitive topics like puberty and risky behaviors. Parents are usually relieved that their child’s physician is discussing these topics, but it’s important to address confidentiality up front, with both teens and parents. Teens need to understand what will be kept confidential so they’ll give you accurate information about health concerns and behaviors. Parents need to understand that you’re all still on the same team, and that you encourage teens to communicate with their families about anything important that comes up.

Your preceptors can guide you, but in general, there is very little that you can’t keep confidential between you and your adolescent patient except concerns about abuse or safety. Confidentiality must be breached if a teen is at risk of harming themselves or others and cases of child abuse or neglect must be reported to child protective services. The definition of statutory rape and reporting laws vary by state, with the age to consent ranging from 16 to 18 years old.

State law also governs which health care services minors can access without parental consent. For example, in Washington, any adolescent can receive reproductive health care and prenatal care without their parents’ consent, and those 13 and older can access mental health services and substance use treatment independently. Patients 18 and older are considered adults. Current information on consent laws by state can be found at the Guttmacher Institute’s website ( https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law ).

Interviewing techniques

Teens tend to be a lot more reticent than younger children or adults, so open ended questions often don’t work as well. If you ask questions like “how’s school?” you’re likely to get “fine” or “ok.” If you ask specific questions like “what did you do after school yesterday?” you’ll learn much more about what’s going on with your teen patient.

It’s especially important to ask about risky behavior. Adolescents are establishing their autonomy but may not have the judgment to keep themselves safe. The prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for planning and impulse control, isn’t fully mature until the mid-20s, so pediatricians often consider “adolescence” to extend to 21. Late adolescents tend to have better impulse control than younger teens, but are still more likely to take risks than they will when they’re older.

HEADSSS Assessment

HEADSSS is an acronym for psychosocial topics important to cover with teens – you’ll see many clinicians use it to guide their interviews. The original acronym was HEADS – as in getting into adolescent heads – but more S’s have been added over time. Possible questions for each topic are in the dropdown.

Knowledge check

Physical exam

The general approach to the PE in adolescents is the same as for adults. Be thoughtful and talk to your preceptor about whether a parent or a chaperone should be in the room for any part of the exam – there’s no single right answer

Older adults

In the United States, one in three primary care patients is over 65, and that number is expected to double by 2050. In almost every specialty, physicians will be caring for more and more older patients.

The 4M’s framework is an evidence-based approach to age-friendly healthcare, intended to promote high-quality care across settings. It focuses on four core elements of care for older patients:

- What Matters

- Mobility

- Mentation

- Medications

What Matters

What Matters Most is the starting point for the 4Ms. When people have multiple health conditions, as many older adults do, their healthcare may not address their personal priorities or may even become burdensome to them. People differ in what they are hoping for and what kind of care they are willing and able to do. The only way to understand what matters most is by asking our patients and their families.

With your hospital patients, you may start with a simple question such as, “What are you hoping for from this hospitalization?” Patients may share that they want to avoid a nursing home, or want to stay connected with friends and family, or they may express preferences for more pain control versus more lucidity.

In the primary care setting, asking patients What Matters is important to recommending care that is aligned with a patient’s values. For example, a patient who values longevity may want more appointments, testing, and medications compared to a patient who values time away from medical settings and fewer medical interventions. You could ask simple questions like, “What activities give you joy and meaning?” or “Who are the most important people in your life?”, followed by a simple question like, “What is one thing that you want to focus on today so you can do more of an activity or spend more time with a person that is important to you?”.

Another component of What Matters Most is advance care planning, which is a type of conversation or documentation that reflects a patient’s preferences for care in serious illness or terminal situations. The traditional advance care directive, or Living Will, directs treatment only when someone has a terminal condition or is permanently unconscious. These clinical situations are uncommon, so Living Wills are often of limited utility.

A patient can designate one or more durable powers of attorney for healthcare (DPOA-HC) who can take over decision-making if they are incapacitated. By law, if a DPOA hasn’t been designated, health decisions fall first to the patient’s spouse or registered domestic partner, then to their adult children, then their parents and then their adult siblings. If these default decision makers are estranged, have differing beliefs, or suffer from medical or cognitive issues of their own, it may be particularly important to identify a DPOA whom your patient trusts.

POLST or MOLST (Physician or Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) forms outline patient preferences for resuscitation and other treatment, such as respiratory support, hospitalization, artificial feeding, and antibiotics. A POLST or MOLST follows the patient across care settings and can guide many decisions that EMTs or ED physicians may need to make in the face of an acute issue.

Sometimes these topics can seem daunting to patients. Resources such as Prepare For Your Care can provide a framework for conversations with family members, DPOAs, and clinicians. This website also has patient-friendly DPOA-HC and Advance Directive documents.

Mobility

Mobility is the next key assessment for older adults. Most are still able to manage independently, and in the community, only one in five people over 85 require any assistance with self-care. However, one-third of older adults fall each year and falls are the top cause of fatal and non-fatal injury in this population.

Falls are not an inevitable part of aging. They usually have multiple contributors, both intrinsic to the patient (like vision loss, neuropathy, leg weakness) and extrinsic to the patient (tripping hazards in the home, not using an assistive device). Proactively identifying and addressing these risk factors may prevent a fall that could change (or end) your patient’s life.

All older adults should be screened yearly for falls. Many older adults do not bring up falls with their providers. A simple question such as “Have you had any falls since your last visit?” or “Do you feel unsteady when walking” are effective screening questions. Screening for fall risk can also be done with physical exam, using a test called the Timed Up and Go (TUG). There is an optional video at the end of the chapter demonstrating this exam.

- Mark a line on the floor or identify another object 10 feet from the patient.

- Give your patient the following instructions: “Rise from the chair, walk to the line, turn, return to the chair and sit down again.”

- Time your patient as they perform this task. People who take more than 12 seconds have limited physical mobility and are at high risk for falls.

If a patient screens positive for falls or indicates that they have a fear of falling or feeling unsteady on their feet, this warrants further evaluation of their fall risk factors and a targeted plan to address the possible contributors. Interventions that could support your patient include:

- Physical therapy can improve strength and balance and provide recommendations for an appropriate assistive device such as cane or walker

- Occupational therapy can identify and address safety risks in the home environment

- Adaptive devices for the home such as shower chairs and grab bars

- Vision and hearing evaluations for older adults with hearing impairment and visual impairment

- Addressing musculoskeletal pain or neuropathy contributing to falls

- Stopping or tapering medications that could be contributing to falls or dizziness

- Social supports can “fill in” for identified impairments – i.e. Meals on Wheels, Access van transportation, or in home caregivers

Mentation

Memory and mood should be assessed yearly or any time concerns are brought up by family. Cognitive impairment is common – three percent of those over 65 suffer from cognitive impairment, and the prevalence doubles every 5 years after that. Some memory concerns can be a part of normal aging. The Alzheimer’s Association has a helpful resource may help people differentiate differences between normal aging and more concerning cognitive changes. Not all cognitive impairment develops into dementia and approximately 50% of dementia is preventable. Ways to promote brain health include regular aerobic exercise, social connection, healthy diets, addressing vision and hearing impairment, reducing the use of harmful medications (particularly medications with anticholinergic side effects) and addressing chronic conditions like hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Other contributors to cognitive impairment that include behavioral health conditions like depression, anxiety and PSTD, and sleep disorders like sleep apnea.

The Mini-Cog is a quick and well validated way to screen for cognitive impairment and is commonly used in the clinic.

Step 1: Three word registration.

Look directly at your patient and say “Listen carefully – I am going to say three words that I want you to repeat back to me now and try to remember” After listing three words, ask the patient to repeat them, giving them three chances to repeat them back.

Step 2: Clock Drawing.

Give your patient a piece of paper with a circle on it and say: “Next, I want you to draw a clock for me. First, put in all of the numbers where they go.” When that is completed, say: “Now, set the hands to 10 past 11.” Repeat instructions as needed as this is not a memory test and give your patient up to 3 minutes to complete the test. Score 2 points for a normal clock, 0 points for an abnormal clock.

Step 3: Three word recall.

Say “What were the three words I asked you to remember?” Score 1 point for each word recalled.

Interpreting the test. Add up the points for clock drawing and recall. A score of 3 or more indicates a lower likelihood of dementia, although some degree of cognitive impairment is still possible. If the score is 2 or less, your patient needs further evaluation and testing.

Cognitive impairment becomes more concerning when there is a consistent functional impairment. Functional impairment relates to activities that people previously were able to do independently and now consistently cannot do them independently anymore. To assess for functional impairment, ask about activities of daily living (ADLs), which are basic self-care tasks, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) which are more complex tasks.

| Activities in Daily Living (ADLs) | Instrumental Activities in Daily Living (IADLs) |

|---|---|

| Bathing | Managing medications |

| Dressing | Grocery shopping |

| Toileting | Preparing meals |

| Transfers | Using the phone |

| Grooming | Driving and transportation |

| Feeding | Handling finances |

| Housekeeping and laundry |

Medications

Regular review of all medications is the final M of age-friendly healthcare. People over 65 account for 30% of prescription and 40% of over-the- counter medications sold in the United States. One third of older adults take 5 or more medications (polypharmacy) which is associated with both higher healthcare costs, drug-drug interactions, and more nonadherence to treatment.

The risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) is also proportional to the number of medications used. Up to one third of older adults have at least one adverse effect of a drug in a year, and an estimated 20% of hospitalizations in this age group can be attributed to ADEs. Those with polypharmacy have a significantly higher rate of falls, emergency department use and hospitalization.

Contributors to ADEs in older adults include:

- Decreased clearance of medications by the aging liver and kidneys, leading to increased drug levels

- Changes in body composition with increasing fat & decreasing muscle, impacting how drugs are stored

- Increased sensitivity to drugs with anticholinergic properties and to benzodiazepines

- Interaction of multiple medications – the risk of ADEs is proportional to the number of medications taken

The American Geriatric Society Beer’s list identifies drugs that older adults should avoid if possible. Even though some of these drugs are commonly prescribed for younger patients (or are available over the counter), they can cause serious problems in older adults. Here is a link to the “Top 10” medications that we should avoid or use with caution in older adults. This is presented in patient-friendly language.

Knowledge check

Optional videos

The following video demonstrates the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)

The following video demonstrates how to do the Mini-Cog test to screen for cognitive impairment

In the example below, the patient receives 1 point for recalling one word and zero points for an abnormal clock. The video starts at the 1:42 and you can stop at 4:52.

Resources and References

CDC Vaccine App available at Vaccine Schedules App | CDC.

The Cribsiders Podcast “Trauma Informed Care in Pediatrics”

Ted Talk “How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime”

Levine, S. (2009). Adolescent Consent and Confidentiality. Pediatrics in Review. 457-458

Ford, C., Millstein, S., Halpern-Felsher, B., & Irwin, C. (1997). Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 1029-1034

Inside The Teenage Brain | FRONTLINE | PBS

Advanced Directive for Dementia

Lawton –Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL) (alz.org)

Depression is Not a Normal Part of Growing Older | Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging | CDC