Abdominal Exam

Benchmark exam you should be able to demonstrate on completion of FCM:

Inspection

- Observe your patient for increased discomfort with movement.

- Inspect the abdominal contour, observing for distention or masses.

- Inspect the skin as you examine the abdomen, noting scars and skin lesions

Auscultation

- Listen in one place with the diaphragm of the stethoscope until you hear bowel sounds.

Percussion

- Percuss all four quadrants, observing for tenderness and tympany

- Percuss the upper and lower liver margins in the R mid-clavicular line

Palpation

- Palpate all 4 quadrants for tenderness or masses

- Palpate the lower liver edge

- Palpate for an enlarged spleen

Term 2: Recognize common findings on the abdominal exam

- Abnormal bowel sounds

- Percussion tenderness, rigidity and guarding

- Firm or nodular liver edge

- Splenomegaly

Term 2: Perform hypothesis driven exam maneuvers:

- If you suspect renovascular hypertension: Listen for renal artery bruits.

- If you suspect appendicitis: Assess for McBurney’s point tenderness

- If you suspect cholecystitis: Assess for Murphy’s sign

- If you suspect ascites: Test for a fluid wave and shifting dullness

- If you suspect aortic aneurysm: Assess the diameter of the abdominal aorta using palpation.

Immersion. Landmarks & structures

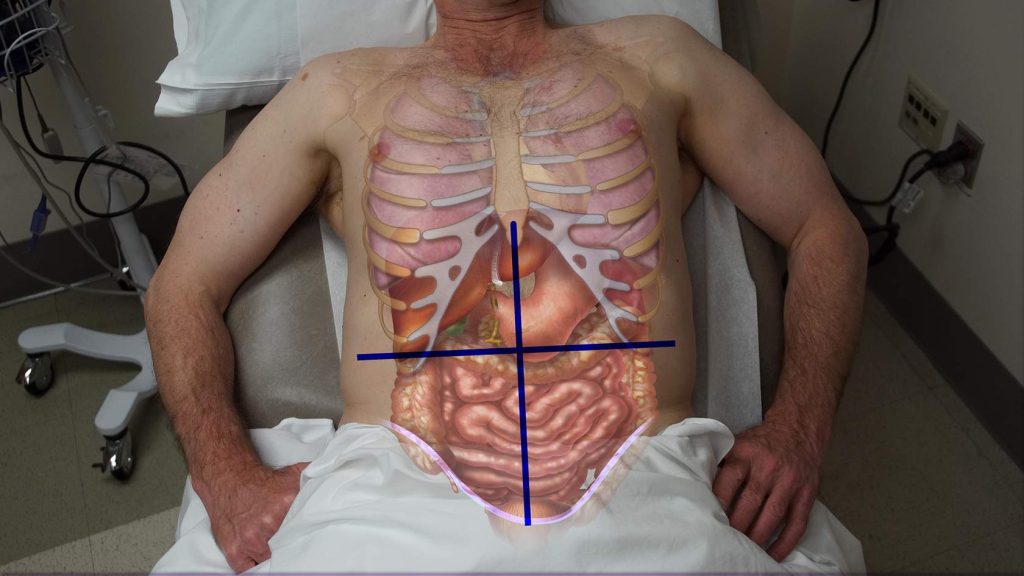

Identify the four quadrants of the abdomen and consider the organs that are found in each one.Tenderness that localizes to one quadrant suggests a different set of diagnoses than pain in another quadrant.

Imaginary lines cross at the umbilicus, dividing the abdomen into right upper, right lower, left upper and left lower quadrants. The liver and gallbladder are in the right upper quadrant (RUQ). The stomach is in the LUQ, with the spleen behind it. The colon is the large tubular structure below, which loops from the RLQ, up to the RUQ, across to the LUQ, and down again to the LLQ.

|

|

-

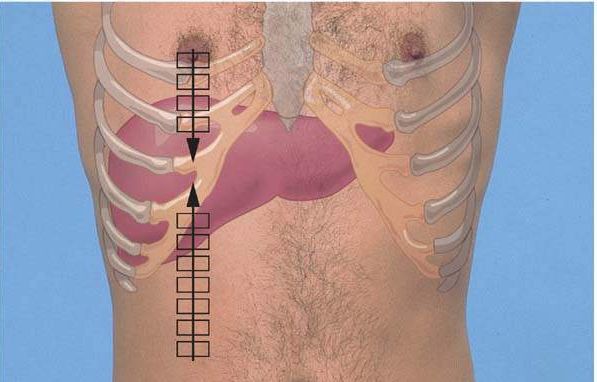

- Craniocaudal: from just below the diaphragm to the right costal margin

- Side-to-side: from the right chest wall almost to the left midclavicular line

Immersion. Exam Steps

Stand on the right side of your patient, who should be supine and double draped so only the abdomen is exposed.

To relax the abdominal muscles and improve the quality of the exam, your patient’s head should be supported by a pillow, their knees should be slightly flexed and their hands should be on the chest or by their sides. Your hands should be warm and any painful area of the abdomen should be examined last.

Inspect the abdomen

Observe the contour of the abdomen for distention. Note any scars.

Auscultate the abdomen in one place

In contrast to other organ systems, auscultation is done before palpation and percussion. Palpation might increase intestinal motility despite a serious illness and falsely reassure the examiner.

Normal bowel sounds are gurgling, lower pitched, and vary over time and from person to person. The frequency is anywhere 4-34/minute. Keep your stethoscope handy and listen to your own bowel sounds before and after a meal and at other times during the day. To say that bowel sounds are truly absent, you must listen for two minutes. Absent bowel sounds suggest a serious intra-abdominal problem.

Percussion

Percuss all four quadrants assessing tympany.

The normal abdomen is tympanitic to percussion over gas-filled bowel and dull over areas filled with fluid or stool. Your findings may shift and change with time and movement of the contents of the stomach and intestine. Masses are also dull to percussion and will not change.Percussion may also elicit tenderness in a patient with abdominal pain.

Percuss the liver.

Percuss along the R MCL from the mid-abdomen up toward the liver. The transition from tympanitic to dull estimates the lower edge of the liver. If your exam partner is comfortable, you can also percuss the upper edge of the liver. Begin in the mid-thorax and percuss along the R MCL down toward the liver. The normal liver span on percussion is < 13 cm.

Palpation

Palpate all four quadrants of the abdomen

Position your patient flat on their back, with the knees bent to relax the abdomen. Start with light palpation, using the flat part of the hand and the pads of the fingers. Lift the hand to move it from one point to another, to avoid tickling your patient. If the patient has pain, palpate the painful area last.

Next palpate more deeply, to detect any masses. Place your non-dominant hand on top of the dominant hand, using the top hand to push the examining hand inwards.

Palpate the liver edge.

Place your right hand on the abdomen in the R mid-clavicular line, below the inferior border of the liver you found by percussion. Ask the patient to inhale as you feel for the liver edge coming down to meet your fingertips. If you don’t feel it, move your fingers 2 cm up and repeat until you reach the costal margin.

The liver edge may be palpable just at the costal margin or may not be palpable at all. In patients with hyperinflated lungs, the normal liver edge may be felt lower down.

Palpate for an enlarged spleen.

Reach across the patient’s body. Place your left hand under the patient’s lower left rib cage and lift slightly. Palpate for the tip of the spleen with your right hand. If you suspect splenomegaly, begin at the level of the anterior iliac crest and move up – the enlarged spleen can extend to the pelvis and into the right lower quadrant.

The normal spleen is not palpable in adults but may be palpable in some healthy children.

Immersion. Documentation

Abdomen: No scars or distention. Active bowel sounds present. Minimal tenderness to deep palpation in the left lower quadrant without palpable masses. Liver span 9 cm to percussion at the mid-clavicular line, with non-tender, soft edge palpable at the right costal margin with deep inspiration. Spleen not palpable. No inguinal adenopathy.

Immersion. Exam Video

Immersion. Knowledge Check

Term 2. Abnormal findings

Auscultation

Absent bowel sounds suggest peritonitis, complete bowel obstruction, or ileus. You must listen for 2 minutes to say that bowel sounds are completely absent.

Tinkling bowel sounds suggest partial small bowel obstruction. They are high pitched and occur in rushes. .

Percussion

Percussion tenderness suggests peritonitis. Gentle percussion causes pain, either at the site of tenderness to palpation or elsewhere in the abdomen.

Palpation

Rigidity suggests peritoneal inflammation. Rigidity is INVOLUNTARY contraction of the abdominal musculature in response to peritoneal inflammation.

Guarding on the other hand is VOLUNTARY contraction of the abdominal musculature due to tenderness, fear, cold hands, or anxiety.

Firm or nodular liver edge suggests cirrhosis. The liver edge normally lies under the rib cage at the R midclavicular line. A firm, cirrhotic liver is more likely to be palpable than a normal liver. If the liver edge is palpated, feel carefully for clues to cirrhosis. The cirrhotic liver is firmer than normal, and may have palpable irregularity or nodules.

Splenomegaly. The normal spleen is not palpable. If it is palpable, it is enlarged. Common causes of splenomegaly are cirrhosis, hematologic malignancies, and infectious diseases.

Term 2. Hypothesis-Driven Exam Maneuvers

Suspected renovascular hypertension: Assess for bruits

Who: Patients with severe, difficult to control hypertension

How: Listen with the diaphragm of the stethoscope ~ 2 cm above the umbilicus, both in the midline and laterally. Bruits heard over the flanks are uncommon but highly suggestive of the diagnosis. In the example below, you’ll hear bruits plus bowel sounds.

Clinical significance: The presence of a bruit supports the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension but the absence decreases the probability only slightly (LR 0.6)

Bruits in this location can also be heard in up to 20% of healthy people under 40, likely caused by flow through the celiac axis. If you hear a bruit in someone without severe hypertension, no further work up is needed.

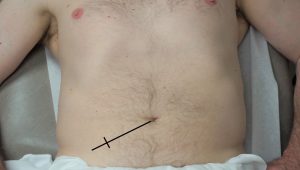

Suspected appendicitis: Assess McBurney’s point tenderness

Who: Patients with RLQ or midabdominal pain +/- nausea & vomiting

How: The anatomic location of the appendix in most adults falls 1/3 of the distance from the right anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus – palpate at this specific point.

Clinical significance: McBurney’s point tenderness supports appendicitis more strongly (LR 3.6) than general RLQ tenderness. Absence of McBurney’s point tenderness argues against appendicitis. (LR 0.4)

Suspected cholecystitis: Assess for Murphy’s sign

Who: Patients with RUQ or epigastric pain, fever, and/or nausea & vomiting

How: Palpate just below the right costal margin in the midclavicular line and observe as your patient breathes in. Murphy’s sign is a pause in inspiration as the tender and inflamed gallbladder hits the examiner’s fingers.

Clinical significance: Murphy’s sign supports cholecystitis (LR 3.2) but its absence decreases the likelihood slightly (LR 0.6). Murphy’s sign can also be observed on ultrasound.

Suspected ascites: Assess for fluid wave & shifting dullness

Who: Patients with abdominal distention

Fluid wave. Place one hand against one side of the abdomen as you percuss the opposite side with your other hand. A positive result is a tap against your hand caused by a wave of ascitic fluid set in motion by percussion. To decrease motion of the soft tissue, which can give a false positive result, an assistant or the patient holds the edge of their hand firmly in the midline.

Clinical significance: The presence of a fluid wave increases the probability that ascites is present (LR 5.0 ) while the absence decreases it (LR 0.5)

Assess for shifting dullness: Starting at the umbilicus, percuss from anterior to posterior, marking the border between resonance (air filled bowel) and dullness (ascites). Ask your patient to roll over partway, and again percuss and mark the border between resonance and dullness. A positive result is a shift in the border as the ascites fluid shifts when your patient rolls over.

Screening for aortic aneurysm

Who: Males > 65 with a history of smoking OR known family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm.

How: Press gently inward in the epigastric region slightly left of the midline to identify aortic pulsations. Now place one hand on each side of the aorta, and measure its diameter. Subtract the estimated thickness of soft tissue.

Clinical significance: The normal aorta is < 3 cm. An aneurysm is > 3 cm and expansile, pushing the hands apart. The larger the aneurysm, the more likely it is to be detected on exam.

Exam is much less accurate in those with an abdominal girth > 100 cm/40 inches. Medicare covers one time ultrasound screening for patients at risk based on criteria above.

Term 2 Knowledge Check

References & resources

- Renal artery bruit for educational purposes, posted on YouTube.

- Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis.

slowed GI motility caused by opioids, recent surgery, or medical illness.