The Physician-Patient Relationship

Every physician-patient encounter has three important goals:

- to gather the information necessary for diagnosis and treatment

- to develop a plan aligned with the patient’s priorities and goals and

- to build a therapeutic relationship.

A trusting therapeutic relationship can increase patients’ satisfaction with their care, boost adherence to treatment, and improve health outcomes. In a 2006 study, 192 Mayo Clinic patients in Minnesota, Arizona and Florida discussed the best and worst experiences they had had with physicians. Base on their comments, researchers identified seven characteristics this population felt contributed to this relationship.

Building a Trusting Relationship

Some patients enter the physician-patient relationship prepared to trust their doctor and in other cases that trust will need to be earned. As recently as 2022, surveys show that US adults place more trust in physicians and nurses than in any other institution. However, there are large disparities in trust along racial and socioeconomic lines, which can be attributed to current and historic discrimination, poor quality care, and unethical treatment. Over the past decade, social media and the pandemic have also increased polarization and decreased trust in our profession and institutions. Empathy and cultural humility, along with honesty, strong communication skills and an attitude of partnership can all help you to build trust in the clinician patient relationship.

Empathy in the clinical encounter

Our patients experience many different emotions during the time we spend together – anxiety, relief, frustration, joy, fear and many others emotions. These feelings may be expressed verbally or non-verbally, more often with subtle or indirect ‘cues’ than with direct statements.

Empathy can be defined as the ability to understand others’ emotions or feelings and can also be expressed verbally or nonverbally, building connection and trust. Respectful silence, offering a tissue, or if culturally appropriate, placing a hand on the patient’s shoulder or forearm are all simple gestures that acknowledge emotion, while statements or questions can reflect and explore someone’s feelings in more depth.

Physicians often overlook opportunities to demonstrate empathy, making patients feel that they haven’t been heard. Attempts to “fix” negative emotions, like encouraging someone who is disappointed or reassuring someone who is fearful, can also make people feel unheard. An empathic response is a better alternative.

The PEARLS framework suggests empathic responses to patient emotion. As you learn to communicate with patients, mnemonics and frameworks like PEARLS can be a good starting point. Communication with patients is not ‘one size fits all’ – the suggested phrases below would feel natural to some physicians and inauthentic for others. Try out these phrases or others that seem to fit better to you. With practice, you will eventually be able to respond to emotion naturally, in a way that is authentic and genuine for you.

In your first interviews, it may be quite difficult to balance collecting medical information and attending to emotion. Don’t worry – as you gain comfort with the content and process of the interview, you’ll have more and more cognitive space to respond empathetically.

Cultural humility in the clinical encounter

Culture can be defined as the shared language, practices, and routines of a social group and every clinical encounter is influenced by three cultures: the patient’s, the clinician’s, and the culture of medicine. Cultural practices and beliefs are dynamic and ever changing, and most people participate in multiple cultures simultaneously. Each individual’s culture is also shaped by many factors – their place of origin, education, religion, race, gender identity, profession, sexuality, and so on.

Given this complexity, it’s critical to approach patients and families with cultural humility, which is a lifelong commitment to reflecting on our own beliefs, values and identities and to learning about those of our patients. Cultural humility recognizes that our knowledge of our patients is limited so we need to bring bring curiosity and respect to every encounter. It also encourages us to level the power imbalance inherent to the physician-patient relationship.

Cultural competence is an earlier approach that emphasized knowledge about other cultures and cultural practices. While it can be helpful to know some general information about specific communities, individuals have many separate and intersectional identities. Stereotypes or generalizations about an entire culture are not likely to be accurate for every individual – for example not every American likes apple pie and baseball – so we now emphasize cultural humility in this context.

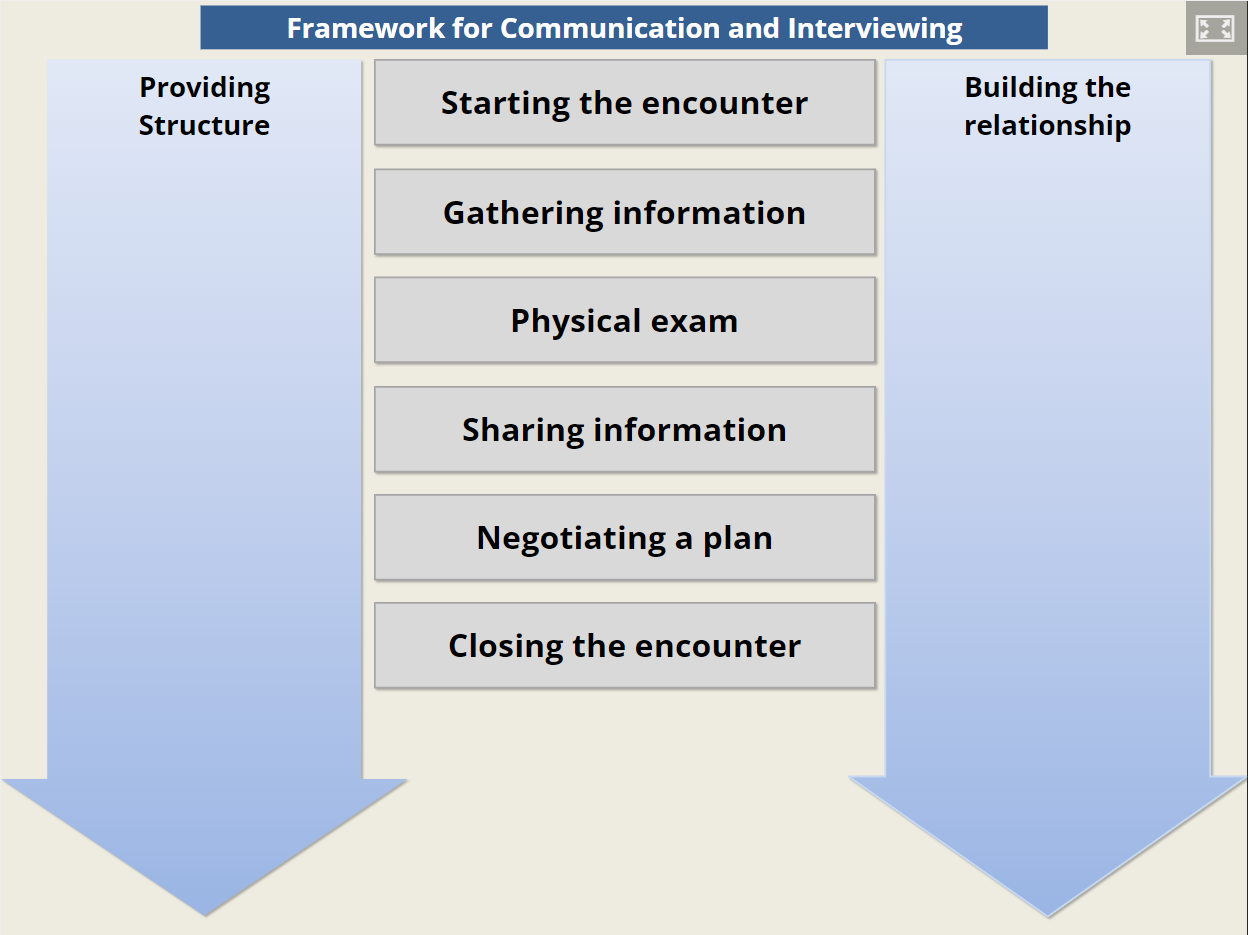

Framework for Communication Skills

Each of the three goals of the patient encounter – relationship building, information gathering and treatment planning- rely on effective communication, both the interpersonal skills you’ve learned over a lifetime and new communication skills unique to the clinical setting. Patient-centered communication can

The Calgary Cambridge model of communication skills, developed by Kurtz and Silverman, integrates the process and the content of a patient-centered medical interview. The interactive graphic below, adapted from Calgary-Cambridge, shows the toolkit of communication skills and techniques you should develop over the course of medical school. Each section shows a set of learnable skills – take a moment to explore the skills related to relationship building.

Nonverbal behavior

Over half of human communication is non-verbal and in the clinic, research shows that nonverbal cues have a significant impact on patients’ satisfaction with their care. American clinicians who smile, lean forward, nod, and use more eye contact and gestures have more satisfied patients. More time reading the medical chart has the opposite effect. But the same cue can have a different impact in different cultures and contexts. For example, in a study in Pakistan, most patients agreed that eye contact is a sign that their doctor is paying attention but people preferred brief eye contact to prolonged gaze, which many said made them uncomfortable.

Of course there isn’t a nonverbal cue dictionary for everything that may make your patients, with their intersectional identities and cultures, more or less comfortable. As with all clinical skills, maintain self-awareness, read the room and adapt as needed.

Positioning & posture

Human interactions occur in different spatial zones that convey different messages. Formal communication occurs in the ‘public zone’ 12-20 feet away. The ‘social zone’, 4-12 feet from the individual, is the preferred zone for the first phase of a patient visit. If the conversation becomes more serious or emotional, clinicians may move into the ‘personal zone’ from 1.5 to 4 feet away. The physical exam also occurs in the personal zone and in the intimate zone, touching the patient. Entering the personal or intimate zone too quickly or without notice can be uncomfortable or threatening.

Connection is facilitated by an open posture, facing the patient or at a slight angle with arms uncrossed. If using the EHR, at least the first minute or two of the visit should be spent looking at the patient rather than the computer. Sitting upright or leaning forward slightly can indicate interest.

Touch

Touch can convey care, concern and emotional support but should be used thoughtfully. Touch on the arm or shoulder is comfortable for most people, while touch on the knee may be appreciated by some and unwelcome for others. In the Pakistani study mentioned above, 88% of men and 74% of women appreciated touch as a gesture of respect, empathy, or healing. Three-quarters of respondents were comfortable and only 1% were uncomfortable with touch on the shoulder. In contrast, the majority was uncomfortable with touch on the knee.

Rapport & partnership

Rapport can be defined as ‘a harmonious relationship’. In medicine, it relates to collaboration and partnership between patient and physician:

- Exploring and respecting your patient’s needs, perspective, views and ideas

- Providing support and communicating your willingness to help

- Sharing your thinking about what is going on

- Acknowledging emotions and demonstrating empathy

Establishing initial rapport: Starting the encounter

Rapport is established at the very beginning. Knock before entering the hospital or clinic room and ask their permission to come in. Introduce yourself warmly by name, pronouns and role.

Then confirm your patient’s identity with their full name and ask them how they’d like to be addressed. They may prefer to be addressed formally (Mr. Smith) or informally (Jamie), or they may share a name different from the one in their medical records. If your patient shared their pronouns asked you to address them with a gendered title (like Mr. or Ms.) you can avoid mis-gendering them by following up with a phrase like those below.

MS1: “Could you confirm your gender and age for me?“ OR

MS1: “If I refer to you by a title, like ‘Dr.’, ‘Ms.’, or ‘Mr.’ which should I use?” OR

MS1: “Throughout my notes and in discussions with my colleagues, do you have a preference of how you’d like me to refer to you ?”

Once you’ve confirmed your patient’s identity, greet any guests in the room, establish their relationship to the patient and confirm that your patient is comfortable with their presence during the interview and exam. A minute of ‘small talk’ about your patient’s day, occupation or interests can also build an early connection.

Demonstrating partnership: Agenda-setting

Collaborative agenda-setting is a patient-centered approach to planning how a patient visit will be spent. The clinician elicits the complete list of concerns that the patient would like to address and adds any other issues they feel are important. Then, patient and physician decide together what to cover that day. This is an important skill, and we’ll spend more time on it before you start in your primary care clinic.

- Indicate the time available. “We have about 20 minutes together today.”

- Forecast what you would like to have happen. “I know you want to talk about the shoulder pain you’ve been having, and I want to follow up on your blood pressure.”

- Elicit other concerns that your patient would like to discuss. “What else would you like to discuss today?“

- Confirm the list of concerns and screen for other issues, like need for medication refills, forms filled, etc.

- Decide together how to spend the visit, taking both perspectives into consideration.

For hospital tutorials, the process will look a little different but you should still set an agenda to orient your patient to the interview process.

- Indicate the time available. “I have about an hour and a half to spend with you.”

- Forecast what you would like to have happen. “I’d like to hear about the shortness of breath that brought you in to the hospital, then get a complete picture of your health history and perform an exam of your head and neck, heart, lungs, abdomen, nerves and muscles. Does that sound ok?”

- Elicit other concerns. “Is there anything else happening this morning? Tests or consultations? Anything else I should know?”

Discussing confidentiality and confirming consent

For hospital tutorials, let your patient know that we are not part of their healthcare team and will not share information with their physicians team or write in their chart. The only exception is if they are thinking of harming themselves or someone else. Should a patient ever report this to you, discuss it with your mentor immediately.

“I’m not part of your team, and I won’t share any information with your team or in your medical record. The only exception is if you tell me that you are considering harming yourself or someone else – I would need to tell your doctor about that.”

Confirm consent by asking your patient if all of this sounds ok. Your mentor or patient interview coordinators have already gone through a more formal process of describing what will happen and obtaining each patient’s consent. If your patient expresses any reluctance or concerns, check in with your mentor on how to proceed.

References and resources

Epstein RM and Street RL (2011). The Values and Value of Patient Centered Care. Annals of Family Medicine 9(2):100-103. LINK

Street RL, Makoul G et al (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 74(3):295-301 LINK

Ahmed, A., van den Muijsenbergh, M. E. T. C., & Vrijhoef, H. J. M. (2022). Person-centered care in primary care: What works for whom, how and in what circumstances?. Health & social care in the community, 30(6) LINK

King A, Hoppe RB. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. (2013) Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 5(3):385-393. LINK

Wang, D., Liu, C., & Zhang, X. (2020). Do Physicians’ Attitudes towards Patient-Centered Communication Promote Physicians’ Intention and Behavior of Involving Patients in Medical Decisions?. International journal of environmental research and public health. LINK

Kurtz S, Draper J and Silverman J. (2005) The ‘what’: defining what we are trying to teach and learn. Chapter 2, Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. CRC Press, London, England.

Khan FH, Hanif R, Tabassum R, Qidwai W, Nanji K. Patient Attitudes towards Physician Nonverbal Behaviors during Consultancy: Result from a Developing Country. ISRN Family Med. 2014 Feb 4;2014:473654. doi: 10.1155/2014/473654. PMID: 24977140; PMCID: PMC4041264.

Approaches to building rapport with patients. Clin Med (Lond). 2021 Nov;21(6):e662-e663. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2021-0264. Epub 2021 Oct 12. PMID: 34642167; PMCID: PMC8806294.

Hollis RS. Caring: A Privilege and our Responsibility. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 83(1) 1994.

Bendapudi NM, Berry LL et al. Patients’ Perspectives on Ideal Physician Behaviors (2006). Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 81(3): 338-344. LINK.

Perlis RHOgnyanova KUslu A, et al. Trust in Physicians and Hospitals During the COVID-19 Pandemic in a 50-State Survey of US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2424984 LINK

Howe, L. C., Leibowitz, K. A., & Crum, A. J. (2019). When Your Doctor “Gets It” and “Gets You”: The Critical Role of Competence and Warmth in the Patient-Provider Interaction. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 475. LINK

Khullar D. (2018) The Upshot: Do You Trust the Medical Profession? New York Times, 01/23/2018. LINK