8-3 Supporting Early Cognitive Development

A – Early Cognitive Development

There are many ways to support young children’s early cognitive development. In this section of the session, we focus on supports in three main areas:

- Designing learning environments (materials, spaces, tools)

- Providing social support (positive and responsive interactions and modeling)

- Planning learning experiences (interactive, theme-based activities)

Learning Environment: Materials

In thinking about materials to support science learning, consider materials that are:

- Open-ended, meaning they can be used in multiple ways and allow for creativity, investigation, and problem solving.

- Varied in size, shape, and texture.

- Relevant to the children’s interests.

Learning Environment: Nature

The outdoors is one example of an optimum learning environment to support early cognitive development. Nature provides one of the best environments for children’s spontaneous exploration, play, and learning. A park, a field, a yard—any outdoor space is beneficial.

Direct experience with the natural world provides opportunities for problem solving and observation. The outdoors provides a wide variety of sensory experiences. Children can observe different textures, smells, and sounds. They can compare living and non-living things. This encourages informal learning as children explore and make discoveries.

The diverse materials found outdoors also facilitate imaginative play. Children can use plants, stones, and sticks to count, build, and create. Even in urban environments, outdoor play brings children into contact with nature. Children can feel the wind and watch how it moves objects like leaves or paper. They can see changes created by sunlight coming into contact with surfaces. They can experiment with shadows and reflections. They can describe and draw or count the kinds of clouds they see.

B – Socially Supporting Development

Children construct knowledge through social interactions with peers and adults. Socially supporting children’s development requires using our observations about what children say and do to learn about their interests and current understandings.

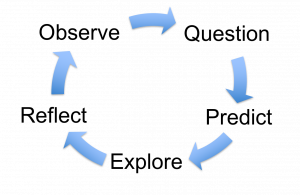

When we operate from this perspective, educators and children become scientists together in a process of collaborative inquiry:

- Expressing curiosity

- Asking questions

- Exploring and investigating

- Sharing ideas

Social Support: Scaffolding

Adults play a fundamental role in guiding children’s STEM learning. Educators may add new information or facts that children may not know and ask additional questions that children may explore.

By observing what children are doing and then asking questions and working with them as they puzzle through their own understanding of the world, adults can, in a sense, walk them through increasingly complex ways of thinking.

Scaffolding is a term that describes techniques adults can use to support and help children in their learning. Scaffolding is offering the right level of learning support to take a child’s knowledge to the next level. Just as a scaffold supports construction of a building, adults can scaffold a child’s experience as they are learning.

To scaffold an experience, adults can assist children by cuing, prompting, questioning, modeling, discussing, and explaining when children indicate they need this support. Using these tools, adults can stretch children’s learning to a new level.

An adult can ask a child what they are doing and help them express their observations. Adults can also answer questions about what a child is encountering, define terms, and provide missing information.

Scaffolding is a balance. If we don’t offer enough help, the child can struggle, become frustrated, and give up. But if we offer too much help, the child misses an opportunity to stretch their learning. To find the just-right spot, we have to pay attention to what the child is doing and, in older children, to help them talk about it or think aloud.

A little adult guidance can help young children reinforce their knowledge, correct misconceptions, and extend their thinking to figure out even more than they manage to learn on their own.

Social Support: Guiding Exploration

One way to scaffold learning is to ask open-ended questions that can guide a child’s exploration. This can be useful for children of all ages—even infants can give non-verbal responses.

Adults can engage children in reflection through the process of asking questions, investigating, and constructing explanations.

Start by observing or noting something that is happening. Ask a question about how things will change in the future; Predict what that change might be. Explore the effect it had, and then reflect on what was learned.

Another benefit of scaffolding is that by actively observing individual children, we can assess their understanding of concepts.

Children who are dual language learners, for instance, may understand the concepts we are working on, but they may need assistance developing the English vocabulary to discuss their understandings. Allowing children to speak in the languages that are most comfortable to them is important in fostering curiosity and questioning.

Vide: Making Gak (0:51)

In this video, Making Gak, the same scaffolding approaches are helpful for younger children even though these children are preschool age.

As you watch, think about how the educator scaffolds the children’s learning. Notice the language the educator uses, the questions they ask, and when they ask them.

Video Debrief

How did the educator scaffold the children’s play to support exploration and discovery? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible answers are:

- The educator prompted children to observe what was happening. After adding more water, the educator cued the children to touch the substance and describe how it felt and asked them to keep stirring.

- The educator used questioning to invite children to make predictions. For example, the educator asked, “What happens when I add more water?”

- The educator modeled scientific language by using the word predictions.

- The educator discussed the children’s predictions. After acknowledging the children’s predictions, the educator asked, “Is it blowing up, or is it becoming foamy?”

Using these tools, the educator stretched the children’s learning to a new level.

Social Support: Questioning Mind

Another way to support cognitive development through social interactions is to model a questioning mind. A questioning mind is as simple as it sounds. As an educator, you can model questioning the world around you. Children will see and hear you questioning things and will want to try it out on their own.

You can ask questions, such as:

- “What happened here?”

- “I wonder what this is.”

- “I wonder if other balls of the same color also bounce.”

Learning to inquire is most successfully modeled when educators truly do not know the answer, do not have a preconceived answer in mind, or are clearly surprised by the results of the investigation. It is also helpful when educators are personally curious about the subjects of their inquiries.

As we discussed earlier about imitating actions, infants and toddlers are just as excited about imitating adult’s vocalizations and eventually language.

Remember that even preverbal infants can question the world around them by pointing and looking to an adult or by directing their attention to different objects and areas of interest.

C – Planning Learning Experiences

Open-Ended Opportunities for Exploration

Combining what we have learned about designing learning environments and providing social support for early cognitive development, we can consider how those two ideas intersect when planning learning experiences for children.

Two key themes emerge about learning experiences that support cognitive development. They should be:

- Open-ended opportunities for exploration. Children will naturally want to investigate if they have the opportunity.

- Based on a collaborative inquiry process where you and the child are scientific partners in the investigation of the world.

Scaffolding + Environment

One example of toddlers’ desire to investigate, if given the chance, comes from a study in which researchers showed 2- to 4-year-old children a set of nested cups during a free-play session. The researchers never showed the children how to put the cups together on their own and told them that they could play in any way they wanted. The researchers never directed the children to nest the cups.

When the toddlers had an open-ended playtime with the cups, they spontaneously began to nest the cups on their own, designing different strategies along the way to correct mistakes and to reach goals.

One way to engage children is to present them with an interesting end-state (e.g., the nested cups) and see how they problem-solve from a different starting state (e.g., the array of cups) to get to the end-state on their own. This is also a key time to employ scaffolding techniques by first observing what the child is doing and then asking questions to scaffold their learning.

For example, if a child is trying to use brute force to make a larger cup fit into a smaller one, you could use the emerging mathematical language of quantity comparison to ask, “Hmm… they don’t fit. Is one cup larger than the other? Which one?”

Adults play an important role in arranging this environment to make sure it is conducive for STEM explorations. Educators can support STEM-skill development by providing opportunities to play with open-ended toys like building materials, art materials, shakers or other music-making objects, vehicle and character sets, and sensory and nature stations.

Learning Experiences

Theme-based activities are an excellent way to engage and promote infant and toddlers’ natural motivation to explore and investigate.

You can use one theme to explore many different ideas. For example, a trip to the garden center can be expanded in many ways—you can read books about flowers; observe the different sizes, shapes, and colors of seeds; discuss changes in the seasons; and give children garden props to make their own pretend (or real, depending on available space) gardens.

Here are some examples taken from an Office of Head Start material called A Family Note on Finding the Math. The theme of these activities is building emergent mathematical thinking skills at the park:

- You can use and identify spatial relationships by pointing out different observations.

- With older toddlers, you can ask them to provide their own observations, such as:

- — “The squirrel is on the tree branch.”

- — “The roots of the tree are under the ground.”

- You can use and identify number terms and quantity comparisons like:

- — “Does this tree have more flowers than the other one?”

- — “How many petals do the flowers on this tree have? Let’s count!”

- You can collect stones, petals, leaves, and twigs and create repeating patterns with them to support pattern recognition.

- You can point out different shapes and sizes of trees, play structures, leaves, etc.

- If eating a snack at the park, you can count out crackers or pieces of fruit or ask the children to pick which bowl has more or less crackers in it. Another idea is to make shapes out of the food items on the plate before eating them.

- For infants, you could make shapes on plates and describe each before serving and eating: “Here is a circle made of strawberries. Let’s see how many strawberries are in the circle. Let’s count them—1, 2, 3…“

- For younger toddlers, you could make shapes on plates, talk about each, and see if children can recognize them: “Which one is the circle? Let’s eat the fruit in the shape of circle first. Can you find that plate? Let’s count how many plates we have.”

- For older toddlers, you could start to ask them to make the shapes on their own. You could either show them the finished product and ask them to reproduce it or see if they can do it on their own. Or, you could draw on the plate to give them a structure to follow.

- You could then follow up by asking them to find shapes in the park.

There are countless options and combinations for activities.

Learning Activities

Warm, nurturing, and effective interactions lay the foundation for children’s discoveries and create opportunities for them to share their findings. Interactions with peers and adults encourage the development of scientific knowledge in addition to cognitive skills.

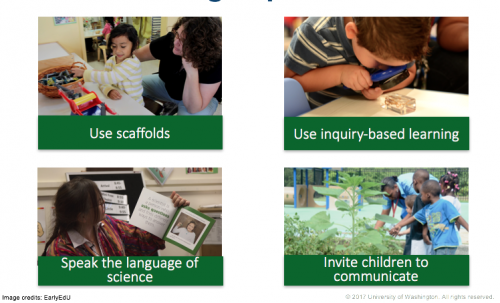

You can use all the support methods in your learning experiences:

- Use scaffolding to encourage exploration in new directions or to provide new information to update children’s developing theories of the world.

- Use inquiry-based learning strategies where the educator and the child are both scientists asking questions and investigating the world together to make new discoveries.

- Speak the language of science, such as:

- More than or less than

- “Let’s test that. Did that cause something to happen?”

Even with preverbal infants, the more exposure, the faster their learning of those terms will be later.

- Invite children to communicate their observations, their questions, and their discoveries. Ask them:

- “What do you see?”

- “What did you find?”

Reflection Point

What are three ways to encourage children’s exploration of the world?

References

References

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). Making gak. University of Washington. [Video File]

Deloache, J., Sugarman, S., & Brown, A. (1985) The development of error correction strategies in young children’s manipulative play. Child Development, 56, 928-939.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.) A family note on finding the math. [PDF]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, Head Start National Resource Center. (2010, July). News you can use: Environment as curriculum for infants and toddlers. [PDF]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Learning environments: Nature-based learning and development. [Online Article]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 8-3 Supporting early cognitive development. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]