6-1 Early Social and Emotional Development: Relationships

A – Relationships

Two of the four Social and Emotional Development subdomains describe children’s development of relationships with other people. These are:

- Relationships with Adults

- Relationships with Other Children

The two areas of relationship building are separate because children do not develop relationships with other children in the same way that they develop relationships with adults.

Relationships with adults start early and have a significant impact on infant’s mental health and growth.

Relationships with other children, such as siblings and peers, tend to develop later and become much more important as children move into increasingly social environments, such as early learning programs or kindergarten.

Relationships with Adults

Just as we learned about language development, social learning requires back-and-forth interactions between children and adults. And as in language development, children start out as passive infants, primarily taking in social information and gradually developing into social partners that both give and receive social information.

We will learn about the different kinds of social relationships that children build with adults as infants and toddlers. First, we will cover the general progression of child-adult relationships.

Then we will discuss two particular forms that the child-adult relationship can take. One form of relationship that occurs in infancy is called attachment. The attachment relationship is between children and their familiar caregivers, not just their parents. The other form of relationship that occurs is called social referencing. As infants get older and move into the toddlerhood stage, they begin to establish relationships with adults as resources in their environment. They will reference adults as sources of social information. This type of relationship most often occurs with familiar adults, but can include unfamiliar adults as well.

Early Infancy: Birth to 8 Months

While infants between birth and 8 months are primarily passive receivers of social information, they can control their social environment through attention-getting behaviors and withdrawal from negative social events.

One way scientists investigate infants’ emerging social competence in early infancy is by using what is called the still-face interaction. During the still-face interaction, parents are instructed to maintain a neutral expression while facing their child and to refrain from responding to their child in any way.

Studies using the still-face interaction have found that infants as young as 2 months are sensitive to disruptions in their caregiver’s responsiveness.

Moreover, the still-face interaction shows that infants do take some control of their social environment.

During the still-face interaction, infants will often smile or cry in an attempt to re-engage the adult and eventually will turn away from the adult as a withdrawal response to a caregiver’s lack of communication. This withdrawal behavior is found across cultures: Chinese, Canadian, and American.

Video: Connecting with Babies (2:37)

Zero To Three’s Connecting with Babies video shows an infant’s reaction in the still-face interaction. As you watch this next video, consider:

- What is infant mental health?

- How much does it affect later development?

Watch Connecting with Babies from ZEROTOTHREE on Vimeo.

Video Debrief

What is infant mental health? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

“Infant-early mental health, sometime referred to as social and emotional health, is the developing capacity of the child from birth to 5 years to form close and secure adult and peer relationships; experience, manage, and express a full range of emotions; and explore the environment and learn . . .” (Zero To Three, 2016)

Here are some facts from Zero To Three about the effects of infant mental health on later development:

- Infants do have traumatic experiences. It is estimated that between 9.5 percent and 14.2 percent of children from birth to 5 years of age experience an emotional or behavioral disturbance.

- Early adverse events can lead to mental health problems in infancy and toddlerhood. Symptoms of depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and other mental health issues can begin to manifest in infancy and toddlerhood.

- Early mental health issues can have lasting effects on development and adult mental health. Research has shown that the emergence of early onset emotional and behavioral problems in young children is related to a variety of health and behavior problems in adolescence, not to mention juvenile delinquency and school dropout.

Reflection Point

Consider these questions:

- What are reasons that parents or families might not want to talk about their mental health or their children’s? What is one way to address concerns?

- How can you begin a conversation about a child’s or family’s mental health?

- Name one mental health resource for families.

B – General Progression

Infants’ development of social relationships with adults begins passively, moves to sharing experiences, and eventually leads to children emerging as initiators of social interactions, such as getting others to smile or comforting a distressed adult.

Between 8 and 10 months, infants begin to try to show adults when they find something like a toy fun or exciting. They begin to display a behavior called anticipatory smiling.

In anticipatory smiling, infants smile at an object and then turn to their caregiver while still smiling. The idea is that the child expects the adult to also smile in response. This is similar to when older children and adults turn to each other to confirm how great something is.

For example, imagine that you found a really cool new object, you might say, “Wow, this is really cool.” and then turn to your friend to see if they share the same sentiment. This is essentially what infants are trying to do with anticipatory smiling.

By 9 months, infants don’t just react to or try to share emotional exchanges, but they also begin to initiate positive emotional exchanges.

By the end of the first year, infants use smiles as an intentional social signal.

And by 2-and-a-half years old, children will even attempt to comfort adults by handing a cold adult a blanket or hugging a distressed adult.

Attachment

Infants often develop attachment relationships with their caregivers early in infancy. This can manifest as attachment behaviors, such as separation anxiety in toddlerhood. These behaviors tend to subside as children’s social understanding develops.

Attachment is a bond we have with special people or objects in our lives. Attachment can occur with both people and inanimate objects, such as lovies, teddy bears, or other treasured items.

Children will form separate attachment relationships with each adult in their lives.

Bowlby’s 1969 model of attachment is the most widely accepted view of attachment today. Bowlby believed in an evolutionary approach to attachment, noting how attachment relationships increase a child’s probability of surviving.

Essentially the idea is that children are predisposed to form attachment relationships in infancy. Infants have built-in attention-getting functions, such as crying, that capture adult attention. Adults then provide caring behaviors to reduce infants’ attention-getting activity. The caring behaviors are positive, which motivate the child to stay close to the caregiver. This is turn means that the child will be safer. So children who do this are more likely to successfully reach adulthood.

Because of these strong social bonds, between 6 months and 2 years, infants and toddlers may develop attachment behaviors, such as separation anxiety.

Separation anxiety is when infants or children are upset by their caregiver’s departure.

These behaviors are a child’s attempt to get the caregiver to stay with them or come back. Note, however, that these behaviors do not always develop or occur. The occurrence depends both on the situation and the child’s temperament. Some children are less inclined to be anxious or concerned and even anxious children may find some situations less anxiety-provoking.

Behaviors like separation anxiety begin to subside around 3 years of age when children begins to understand some of the factors that influence a caregiver’s comings and goings. This is when children begin to negotiate instead.

Features of Attachment

Attachment relationships have four main features:

First, they provide the child with a sense of security. When the caregiver is present, the child feels safe and has the confidence to explore their environment. They don’t feel as secure when the caregiver isn’t present.

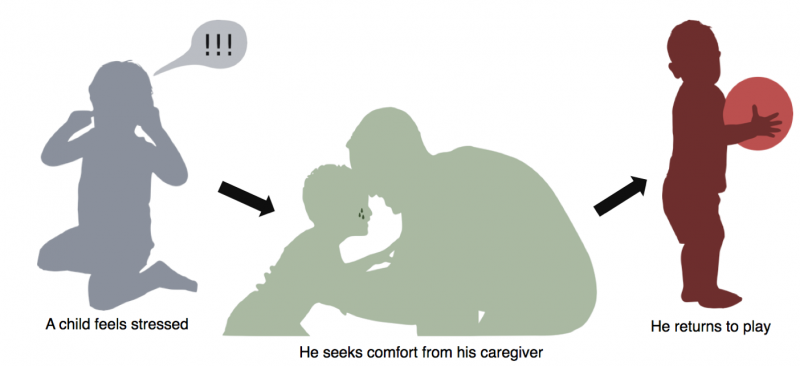

First, they provide the child with a sense of security. When the caregiver is present, the child feels safe and has the confidence to explore their environment. They don’t feel as secure when the caregiver isn’t present. Children also see their caregivers as a safe haven. When children feel unsure in situations, they will turn to caregiver for comfort and safety.

Children also see their caregivers as a safe haven. When children feel unsure in situations, they will turn to caregiver for comfort and safety. Another feature of attachment relationships is called proximity maintenance. Since children rely on their caregiver for comfort when they feel unsure or threatened, they try to remain close to them. Staying close maximizes the caregiver’s availability to respond to them at all times.

Another feature of attachment relationships is called proximity maintenance. Since children rely on their caregiver for comfort when they feel unsure or threatened, they try to remain close to them. Staying close maximizes the caregiver’s availability to respond to them at all times. Finally, attachments are characterized by separation distress. This means that toddlers often experience distress and anxiety when an attachment figure leaves.

Finally, attachments are characterized by separation distress. This means that toddlers often experience distress and anxiety when an attachment figure leaves.Measuring Attachment

There are multiple ways that scientists investigate attachment relationships, often called attachment styles. The most classic test is called the Strange Situation test.

Another test for attachment style is called the Q-Sort test. The Q-sort test is able to evaluate attachment in a much wider age-range (1 to 4 years) than the Strange Situation test and in some ways better reflects everyday life for the caregiver and infant relationship, since it relies on home observations.

However, the Q-Sort test does not discriminate between different types of insecure attachments and is quite time-consuming, since it requires several hours of observation time and then more time spent sorting the observed behaviors.

In the Strange Situation test, experts observe the reaction of an infant to various different situations:

- In a new space with a familiar caregiver (a playroom)

- To an unfamiliar person with the familiar caregiver still present

- To an unfamiliar person (trying to comfort the child) with the familiar caregiver absent

- To the familiar caregiver after an absence

- To the absence of all adults (alone in the playroom)

- To the return of the unfamiliar caregiver (trying to comfort again)

- To the return of the familiar caregiver

Researchers observe each of these situations for the combinations of the child’s approach and avoidance reactions.

There are a variety of different attachment types, the most common form of attachment in the U.S. is called: secure attachment. It is generally characterized by a child’s use of their familiar caregiver as a secure base for exploration, distress at their absence, and comfort with their return.

However, the exact behaviors exhibited must be observed by a trained individual to be evaluated for attachment type.

Note that while attachment behaviors may seem obvious when we summarize them in this way, it takes a lot of training and experience to be able to classify children’s attachment style.

Attachment Behaviors

Researchers have identified three broad attachment behaviors that children use: secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-resistant.

A child who is securely attached to their caregiver tends to explore freely when that caregiver is present. When the caregiver leaves, she is upset, and when the caregiver returns she is happy.

A child with an insecure-avoidant attachment style won’t explore as freely as a secure child and is wary of strangers even when a caregiver is present. When the caregiver leaves, the child is often highly distressed and does not calm easily when the caregiver returns.

A child with an insecure-resistant attachment style does not play freely even when a caregiver is present. When the caregiver leaves, she is not distressed at all and shows no change in emotion when the caregiver returns.

While researchers may classify children’s attachment behaviors as falling into a particular style or category, it’s important to remember that security of attachment is a continuum.

A child also has multiple attachment relationships, and each one can be different. For instance, a child may be securely attached to one caregiver and insecurely attached to another. Children adjust their attachment behavior in response to the caregiving they receive. These behaviors can actually help children adapt to their environment.

For example, insecure attachment behavior, like avoidance, may help a child adapt to a stressful environment. Imagine children whose parents punish or reject them when they cry. The children might withdraw from their parents to avoid crying and angering them.

It may sound like some of these behaviors are easily identifiable. However, it takes a lot of specialized training to fully identify attachment behavior. If you have concerns about a relationship between a caregiver and child, discuss those concerns with a professional.

C – Cultural Specificity

In addition, the prevalence of different attachment types varies by culture. For example, while in the U.S., the predominant attachment type is secure attachment, in Germany, independence in children is highly valued and thus infants are encouraged not to cling to their caregivers.

Because of this cultural difference, the prevalence of the insecure, avoidant attachment type is much higher in German children.

Note that this does not mean that German children are exhibiting unhealthy or maladaptive attachment types. In fact, they are doing the opposite. They are exhibiting the exact social behaviors that are valued in their culture.

In contrast, Japanese babies rarely show avoidant attachment behaviors but do show resistant attachment behaviors. Scientists have suggested that this could be due to infants’ constant proximity to their mothers or primary caregivers. Separation from their caregiver may be associated with increased levels of stress as compared to those of children from different cultures.

Social Referencing

As children begin to develop a wider variety of relationships with both familiar and unfamiliar adults and to recognize social cues from the people around them, they begin to realize the utility of their caregivers for more than just comfort. Between 8 and 10 months, children begin to consult with adults as social resources.

This is called social referencing. Social referencing is when children use another person’s emotional signals to evaluate the safety and security of their surroundings, guide their own actions, or gather information.

Scientists have found that a caregiver’s emotional expression will influence whether a 1-year-old engages in new or unfamiliar activities. For example, 1-year-olds were more fearful and avoidant of a stranger after observing their mother behave fearful or wary of the stranger.

Social referencing doesn’t just apply to people either. In another study, 1-year-olds played less with an ambiguous toy if their mother was inattentive and did not provide social cues about the toy or the playroom.

Visual Cliff Test

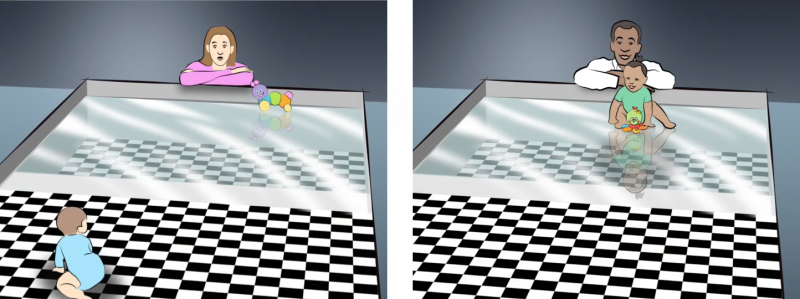

Recently, researchers have used a test called the visual cliff to study infants’ social referencing.

In this test, the child is placed on a table with a checkered pattern. Next to the infant appears to be a drop-off that is about 3 feet high, but in actuality the infant is on a piece of plexiglass that extends across the visual cliff. Crawling across the platform is safe, even though it looks scary.

In the study, researchers placed an appealing toy on the opposite side of the platform. Infants would need to crawl across the perceived cliff to reach it. Their caregivers also stood on the opposite side of the platform with different expressions. Then, they observed whether infants crossed the platform.

On the left we see a picture of a mother with a fearful, worried expression. As a result, this child does not cross the platform to get the toy.

On the right, we see a father with an encouraging, enthusiastic expression. Reading this positive cue from the father, the infant felt safe and confident in crawling across the platform to get the toy.

Caregivers’ expressions influence children’s behavior. This is true of all of children’s attachment figures, including educators.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to support social and emotional development in young children.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

What’s That

Does your child point and say “dat?” Ask your child, “What do you want?” Pick your child up and have him/her lead you to what he/she is pointing at. When you find it, you can say “That’s a spoon!” or “That’s a light switch!”

Ages 1-2

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

From infancy on, babies pay attention to the intentions of other people and want to tell you their intentions. Pointing and saying “dat” is a first step toward learning the skill of communicating intentions. You can help children learn this by finding what they want and help them name it.

Read the Vroom tip. Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

D – Relationships with Other Children

Throughout early childhood, children develop the ability to play and build friendships with other children through parallel play, cooperative play, and turn-taking or pretend play.

Before age 2, children play alone, showing only occasional engagement with other children. As the framework subdomain of relationships with other children notes, by 1-and-a-half years, children start playing next to other children with similar toys or materials. This is called parallel play.

Cooperative Play

By the time children are 2 to 3 years old, their social skills will drastically change. The subdomain on relationships with other children states that by 3 years, most children will join in play with other children by sometimes taking turns or doing joint activities with a common goal, such as building block structures with others or pretending to eat together.

During this time, children are working on skills like taking turns, and their pretend play is becoming more complex.

Play in early childhood gives children experience with building friendships. Conflicts that arise during play are opportunities for learning and practicing social problem-solving skills.

Video: Peer-to-Peer Relationships (58:48)

We’ll listen to a 20-minute interview with early childhood education consultant Donna Wittmer in part of a Teacher Time infant and toddler webinar. The interview starts around 17 minutes and 20 seconds in the nearly one hour long webinar.

The rest of the webinar is also a relevant resource, plus the webinar viewer guide.

Video Debrief

What did you hear about the progression of young children’s relationship skills? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

We took away that young children:

- Develop relationships with other children much earlier than many people realize.

- Six-month-old children prefer to look at photos of infants who are a similar age.

- Older infants may try to comfort another child.

- Once children are 1 year old, peer relationships typically blossom and become more interactive with actions, such as imitation and movement, which have shared meaning.

- At about 30 months, children are becoming even more social.

References

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Erlbaum.

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Basic Books

Campos J. J., Stenberg C. R. (1981). Perception, appraisal, and emotion: The onset of social referencing. In Lamb M. E., Sherrod L. R. (Eds.), Infant social cognition: Empirical and theoretical considerations (pp. 273–314). Erlbaum.

De Rosnay, M., Cooper, P. J., Tsigaras, N., & Murray, L. (2006). Transmission of social anxiety from mother to infant: An experimental study using a social referencing paradigm. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(8), 1165-1175.

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Spangler, G., Suess, G., & Unzner, L. (1985). Maternal sensitivity and newborns’ orientation responses as related to quality of attachment in northern Germany. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1/2), 233-256.

Melmed, M. (2015, June 3). How to prevent mental health problems? Begin at the beginning with infants and toddlers. [Online Resource]

Moore, G. A., Cohn, J. F., & Campbell, S. B. (2001). Infant affective responses to mother’s still face at 6 months differentially predict externalizing and internalizing behaviors at 18 months. Developmental Psychology, 37(5), 706-714.

Sorce, J. F., Emde, R., Campos, J., & Klinnert, M. (1985). Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds. Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 195-200.

Stenberg, G. (2003). Effects of maternal inattentiveness on infant social referencing. Infant and Child Development, 12(5), 399-419.

Takahashi, K. (1990). Are the key assumptions of the “strange situation” procedure universal? A view from Japanese research. Human Development, 33(1), 23-30.

TUBS. (2011, May 4). World location map (W3). [Online image]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages birth to five. [PDF]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, National Center on Early Childhood Development, Teaching and Learning. (n.d.) Infant/toddler Teacher Time webinar series: Episode 4: Can we be friends? Peer interactions and your curriculum. [Webinar]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, National Center on Health. (n.d.). Talking about depression with families: A resource for Early Head Start and Head Start staff. [PDF]

Venezia, M., Messinger, D. S., Thorp, D., & Mundy, P. (2004). The development of anticipatory smiling. Infancy, 6(3), 397-406.

Vroom (2017). Tools and activities. [Website]

Waters, E., & Deane, K. E. (1985). Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1/2), 41.

Zahn-Waxler, C., & Radke-Yarrow, M. (1990). The origins of empathic concern. Motivation and Emotion, 14(2), 107-130.

Zero To Three. (2015) Connecting with Babies. [Video]

Zero To Three. (2016). From feelings to friendships: Nurturing healthy social-emotional development in the early years. [Online Resource]

Zero To Three. (2016, February 10). Infant-early childhood mental health. [Online Resource]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 6-1 Early social and emotional development: relationships. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]