4-2 Steps Along the Way

A – Language Development Journey

A lot happens in the first three years as children prepare to speak fluently. Language learning is not a single part of children’s development. It is a journey with many steps along the way.

Somehow, children blast from listening to speech as newborns to cooing and babbling as older infants. They race from learning new words as toddlers to speaking in complex sentences as preschoolers.

In the Language and Literacy domain of the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework, you can find a wealth of information about some key steps children take along their language developmental progression.

Language milestones are important, but it is how children develop these skills, the path that they take on their journey, that lays the path for later success. So how do children learn language, and what are the best ways to help children become strong language learners? Let’s find out.

From Listening To Babbling

First, how do children go from listening to speech sounds to making speech sounds?

Infants begin by practicing the individual sounds and syllables of the language. In fact, infants make sounds right after birth. While most of what you might hear from an infant is crying, infants can also make other non-speech sounds.

These include sneezing and burping. Then, at 6 to 8 weeks of age, infants begin to coo, practicing long vowels like “ahhhh” and “oooooh.”

Around 6 to 9 months, infants begin to make a series of consonant-vowel sounds, sounds like “mamamama,” “dadadada,” or “babababa.” This kind of babbling allows children to practice making a variety of sounds.

Infants actually have to practice moving their tongues and mouths in the correct way. This helps them to produce the same speech sounds they have been listening to for months. Because listening to language is such a crucial aspect of language development, it is important to ensure children have ongoing, routine hearing screenings.

How much an infant babbles predicts the child’s later vocabulary ability. Infants who babble early and frequently say their first words sooner. They also have larger vocabularies when they begin kindergarten.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to boost children’s early language development.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

A Changing Conversation

When you’re changing your child, make a funny sound. How does he/she respond? By smiling? Kicking his/her legs? Making a sound? Try a new sound and see what he/she does. Keep adding new ones to the mix!

Ages 0-1

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

Back and forth conversations can happen even without words. You are teaching your child about how conversations work. First one person speaks, then the other. This is an early and important lesson about the pleasure and skill of communicating–a skill that’s important in school and in life.

Read the Vroom tip. Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

B – Sounds and Language Patterns

Babbling

But it’s not just a one-way path to language learning. Educators’ and caregivers’ responses to babies’ babbles and coos are important too. In fact, responding to infants’ babbling can actually help support their language development and even lead to larger vocabularies over time.

Research shows that when caregivers respond directly to children’s babbles, rapid language learning takes place. In one study, caregivers were instructed to respond immediately to infants’ babbling. Caregivers based their responses on the specific sounds of infants’ babbling, and they responded using full vowels and full words.

The researchers found that when the caregivers responded to infants’ babbles, the infants dramatically changed the way they were babbling. These infants began making new word sounds based on their caregiver’s responses. These new sounds contained the same patterns that they heard their caregivers make when they responded to their babbling. For example, an infant might look to a caregiver while holding a small doll and say, “Ba!” The caregiver might say, “Oh yes, Mai, a doll! Look at that doll you have, what a nice doll.” In response, Mai might change her babbling pattern to “A-da! A-da!”

Video: Conversations: Uh Oh (0:28)

Next we’ll see a video example of what contingent responding to babbling sounds like in an early learning setting.

In this video, a toddler sits in a high chair eating and babbling while an educator responds to the child’s babbles.

While watching, think about:

- How is this child building language skills?

- How is the educator supporting those skills?

- How do you respond to children’s attempts to communicate with language?

Video Debrief

What did you notice about the infant and educator?(click to toggle expand or collapse)

You may have noticed that:

- The infant is babbling in a back-and-forth way with the educator and making some of the same sounds as the educator.

- The educator is responding to the babbling as if the child is saying understandable words and is repeating some of the child’s sounds.

Becoming a Communicative Partner

In early childhood, communication between educators and caregivers and children develops as children’s language learning develops.

The communicative landscape gradually shifts from a mostly one-way relationship of the caregiver initiating communication with the infant to a two-way communication path as the child learns to become a communicative partner.

As we’ve described, infants start by being immersed in the communicative information provided by their caregivers and then slowly start to embark on their own communicative journey, adding more and more of their own voice to the mix.

Children as Conversational Partners

Let’s take a closer look at how children become conversational partners. We can use the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework to better understand what this development looks like:

- From birth to 8 months, children should participate in back-and-forth interactions, exchanging facial expressions and language sounds with familiar adults.

- From 9 to 18 months, children begin to initiate and participate in conversations by babbling and using gestures, such as pointing, or using words or signs. They also begin to understand the meaning of familiar caregivers’ verbal and non-verbal communications and respond with facial expressions, gestures, words, or actions. And they begin to seek out language-based information, such as the

meanings of new words or the names of different objects. - By 36 months, children begin to use sentences of three or more words and ask and answer simple questions in conversation with others.

Early Vocabulary and Conversation

One way that children become more active communicative partners is by first establishing and then expanding their vocabulary. Children go from babbling to speaking their first word at around 10 to 15 months.

But learning new words is slow in the beginning. Infants say, on average, just over 30 words when they are 15 months old. These words are things that infants encounter on a daily basis, such as familiar people, favorite toys, and clothing. They can also be routines, such as night-night, or sound effects like yum or animal noises.

Children’s vocabulary begins to increase rapidly around the time that that they have learned their first 50 words. This vocabulary spurt often happens sometime during the middle of a child’s second year.

Near the beginning of their third year of life, you may notice that some children also exhibit a spurt in sentence length. In their third year, children’s sentences grow from two-word requests and descriptions to longer sentences of four or more words that allow them to express more complicated ideas.

Reflection Point

Consider these questions:

- What are some factors that might help vocabulary growth?

- What might hinder it?

C – Vocabulary Growth

It is especially important to remember that developmental trajectories are individual and will often depend on many external factors.

Practicing Vocabulary

Different children learn new words at different rates, even after this vocabulary spurt. Sometimes, vocabulary-learning speed can be due to children’s personalities. Children who participate in more conversations typically have a larger vocabulary than their peers. This is because they have simply had more practice talking and using new words to communicate their thoughts and feelings.

The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework indicates that by 3 years of age, children should be able to demonstrate a vocabulary of at least 300 words in their home language.

Interactive: Vocabulary Growth

Interactive: Vocabulary Growth

Use the slider below to explore the graph.

Environmental Factors

It’s not just personality that determines how fast children learn new words. The experiences that children have with language early in life play a very important role. The more that infants hear and interact with language early on, the more vocabulary words they will have later. One factor found to be linked to early language exposure is socioeconomic status, or SES. SES is an economic measure of a family’s resources, including a family’s income, education, and occupation. Children from low-SES families tend to have fewer opportunities to practice language skills, and their vocabularies are more likely to lag behind their more affluent peers.

Growing up in a low-SES family does not cause children to have lower vocabularies. Instead, children from low-SES families often have fewer opportunities to build language skills. For example, parents in low-SES families often have less free time after work. And many child-care centers that are less costly also have larger classroom sizes. This means that there are often fewer opportunities for

one-on-one interaction.

Interactive: Environmental Factors

Interactive: Environmental Factors

Use the slider below to explore the graph.

Data from this same study indicates that while infants from high-SES families hear an average of over 2000 words per hour, infants from low-SES families hear an average of 600 words per hour. By the age of 3, many children from low-SES families will have heard 30 million fewer words than children from high-SES families.

This study was conducted by Dr. Hart and Dr. Risley in 1995. Since then, the study has been replicated by other researchers, who have found similar relationships between the amount of language children are exposed to and the SES status of families.

However, new research continues to indicate that it is not just the number of words that matter. The quality of the language that children hear and engage in is very important. Children build their skills when language occurs in a meaningful context—when we talk to them and engage in back-and-forth interactions.

All parents, caregivers, and educators can provide children with high-quality language experiences, regardless of SES status. We will talk about what elements help bring quality to back-and-forth language-rich interactions a little later in the text.

D – How Children Learn Language

Word Mapping

How do children actually go about figuring out what different words mean and how to use them?

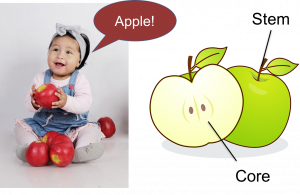

Infants learn new words by mapping, connecting the word that they hear to the thing that it refers to. Children follow other people’s eye gaze and gestures to map words onto objects or events. When they hear a new label, they connect the label to what the adult is looking at or pointing to. For instance, if a parent or educator points to and looks at an object, then says, “apple,” infants begin to map this word onto the object.

Word learning can be challenging for children. Imagine if you had to learn a whole set of vocabulary for a new language. One shortcut that children use to quickly learn the meanings of words is mutual exclusivity. Mutual exclusivity is the assumption that every object only has one label. Say a child is presented with a ball and one other object that they don’t know the label for. If you say a label they don’t know (i.e., the label for the object they don’t know), they will assume that the new label refers to the unknown object, since they already know what a ball is.

Other Strategies

Mutual exclusivity, or assuming that every object only has one name, is not a particularly useful strategy for children who are dual language learners (DLLs). Can you guess why?

Children who are learning two languages must learn that objects can have more than one name. For example, shoe is also zapato in Spanish.

Instead of relying on mutual exclusivity, children who are dual language learners use other strategies to learn words. These strategies often require children to pay close attention to the different properties and structures of language. When children who are dual language learners have enhanced awareness of these language properties, this can help boost their language learning skills, making learning a third language much easier.

We will talk more about children who are learning more than one language later on.

Whether a child is learning one language or multiple languages, talking a lot with children, especially about topics that they are interested in, helps them build their vocabulary. Providing more information about an object while you and a child are engaged in joint attention with that object is an excellent language-learning opportunity.

Overextension and Underextension

Children will also figure out the boundaries of a word’s meaning by using it in ways that adults would not. They may use the word ball to describe any round-shaped object, like an apple, marble, or egg. Researchers call this overextension.

Or they might only say ducky when they see their yellow rubber duck at bath time. But they don’t say ducky when they see another rubber duck or a live duck. This is called underextension.

These behaviors are normal. As children learn more about language and the world, they use words in a more adult-like manner.

Whole Object Bias

All these are strong strategies for word learning. However, they don’t help children when objects have names, like apple, but they also have parts. These parts can have different names, like stem and leaf and core.

Research tells us that children begin associating words with whole objects during their second year of life. Children’s tendency is to associate new words with whole objects, not their parts. This tendency to associate new words with whole objects continues well into the preschool years. This is a typical phase of language development.

As educators and caregivers, it can be helpful for us to know that this is a child’s tendency as they are learning language. We can help children by acknowledging that they named the whole object correctly and then provide more information.

For example, saying, “Yes! That is an apple! Do you see how it hangs from its stem?” The child might repeat “apple!” And we can say, “Yes! An apple hanging from its stem!”

As children learn more about the world and become more familiar with objects, they eventually begin to learn that parts of objects can have different names.

Receptive Language Learning

Children as language learners are not just learning how to produce language but also how to understand it themselves. This is called receptive language learning. Children may even understand a word well before they are able to produce it accurately on their own.

From birth to around 9 months, infants will demonstrate their receptive understanding of language by looking to familiar objects when those objects are named, such as looking at a dog, when mom says, “doggy.”

By the second year of life, 9 to 18 months, we see infants using both their looking behavior and pointing or other gestures to demonstrate their receptive understanding of language.

By the time children reach 3 years of age, the Head Start Early Learning Framework states that they should show understanding of common words used in daily activities, including most positional words, such as up, under, on, or down, and attend to new words in conversations.

Adults may sometimes make the assumption that if a child isn’t saying a word, they don’t really understand it. But that may often not be the case, so it is important to pay attention to children’s receptive understanding of a word, as well as their ability to produce that word in their own speech.

References

References

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Bragg, M. (2014, March 22). The duck drops here: Marines volunteer for 27th Annual Great Hawaiian Rubber Duckie Race [Image 3 of 5]. U.S. Marine Corps. [Online image]

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). Conversations: Uh oh. University of Washington. [Video File]

Goldstein, M., & Schwade, J. (2008). Social feedback to infants’ babbling facilitates rapid phonological learning. Psychological Science, 19(5), 515–523.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1999). The social world of children learning to talk. P. H. Brookes Publishing.

Overdrive_cz. (2007, January 30). Dog nurse VI. [Online image]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages birth to five. [Website]

Vroom (2017). Tools and activities. [Website]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 4-2 Steps Along the Way. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]

Developmental progressions are the skills, behaviors, and knowledge that children demonstrate as they move toward goals in different age ranges.