5-2 Literacy

A – Literacy

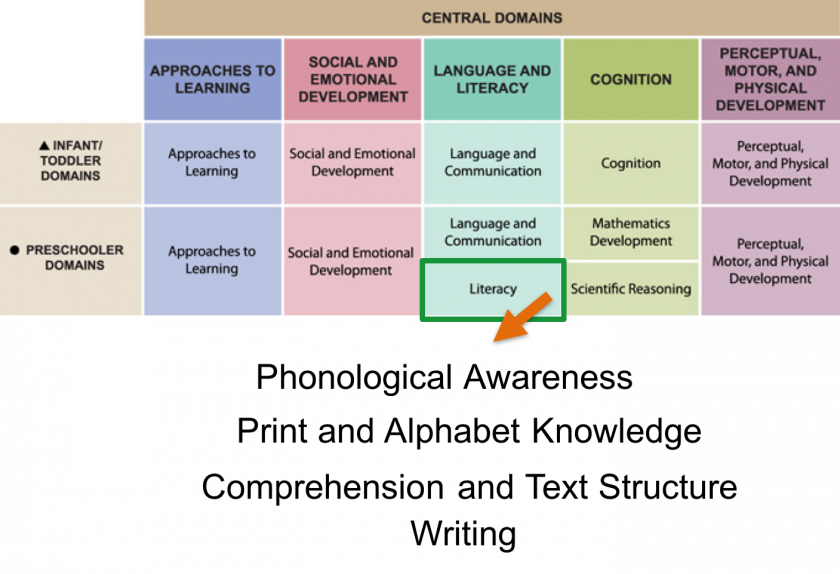

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework

Now let’s look at the second section within preschool Language and Literacy—the Literacy domain.

The Literacy domain includes the development of skills that are important for reading and writing, such as understanding that spoken language is composed of smaller segments of sound, being able to identify the letters and sounds of the alphabet, understanding narrative structure, and exhibiting emerging skills in writing letters and marks.

For example, the developmental progression of the Phonological Awareness subdomain shows the growth from imitating rhymes and alliteration to being able to identify which words rhyme and the ability to count syllables. The other three subdomains are: Print and Alphabet Knowledge, Comprehension and Text Structure, and Writing.

Reading and the Brain

Before we jump into Literacy development within each of the subdomains, we are going to spend a few minutes talking about the brain development that accompanies learning to read.

Reading is a complex task for the brain. Think about all the tasks that your brain has to do to recognize and read a word.

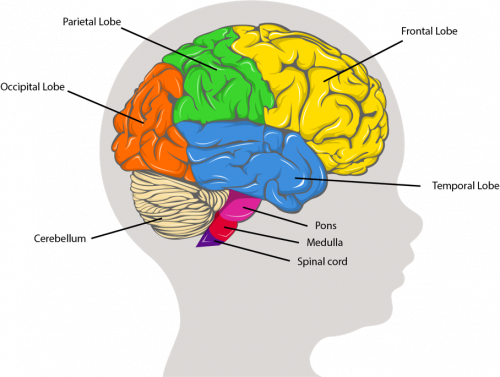

First our brains have to decode printed text. Information about the world comes in through our eyes and moves to visual areas of our brains, where we decode the complicated symbols and patterns.

Once our brains have recognized the symbols and patterns as a word, our brain has to match that image of a word to a sound—the sound that you hear internally when you read a word on a page. Then your brain has to figure out what this sound means. And this whole complex process happens in less than a second.

Children learn language through being surrounded by language and through everyday conversations with the people in their lives. While language skills develop over years of practice, it is a process that the brain is built to learn. Newborn babies are born ready to learn language.

Learning to read is different. Literacy skills, or the ability to decode written symbols and make meaning from them, are built on spoken language skills. Unlike language, the brain is not born to read. Learning to read takes years of tailored instruction and hours and hours of practice. Learning to read actually requires changing the wiring or connections between regions of our brains.

The brain has to combine visual, auditory, and language information in new ways. This takes years of practice. But just imagine all the new connections that are forming in children’s brains as they learn to read.

Phonological Awareness

Now that we have a better understanding of the complicated task that all children face when learning to read, let’s look at the different literacy skills that children are building between 3 and 5 years of age.

One important skill is phonological awareness. Phonological awareness describes children’s ability to recognize the smaller units of sounds that make up spoken words.

These small units of sounds are called phonemes. We can combine phonemes to create syllables and words. Being able to understand and identify phonemes, the sounds that make up words, is an important pre-literacy skill.

As an example, let’s use the word dog. What if a child is not able to hear or understand that the sounds /d/, /o/, and /g/ make up the word dog? It will likely be very challenging for that child to match those sounds to letters and then to combine the letters to form a word.

Producing Consonants

Children may be able to tell the difference between different sounds before they are able to produce all of the sounds themselves correctly.

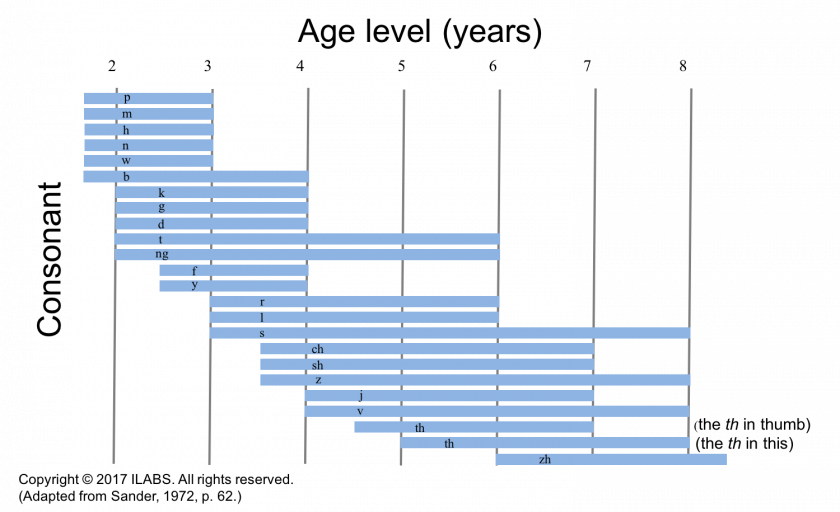

This chart shows the age at which children are typically able to produce different consonant sounds in the English language.

Consonants like /m/, / b/, and /p/ are relatively easy to produce, and children whose home language is English are able to make those sounds earlier in life. Note that some sounds are quite tricky and children typically aren’t able to pronounce those consonants until they are older.

One classic example of this is called the fis phenomenon. In this example, a child calls his toy fish, fis, but when adults call his toy a fis he refuses to accept that this is the correct label for the toy. He will only accept the full fish label for the toy from an adult.

This indicates that even though the child may not be able to make the sound, they know what the sound should sound like and can tell the difference.

Rhyming

Between 3 and 4 years old, children show development of phonological awareness skills by imitating and enjoying rhymes and alliteration. With help, children may be able to figure out if two words rhyme or if they begin with the same letter.

Between 4 and 5 years, children’s ability grows to pick two words that rhyme from a set of three. For example, they may be able to pick the two rhyming words from the list of: bat, mat, and dog.

And, they develop the ability to figure out what is wrong with some phrases and how to fix them. For example, they can decide what is wrong with Twinkle twinkle little car and a way to fix it by replacing car with star.

Children also gain skills in counting syllables and identifying sounds in words. Think back to our recent dog example. By the age of 5 years, children should be able to understand that the sounds /d/ /o/ and /g/ make up the word dog.

These skills set the foundation for later literacy development.

Video: Tapping Syllables (1:40)

Watch this video, called Tapping Syllables, of children clapping the syllables of their favorite characters.

While watching the next video, think about these questions:

- What tools is this educator using to help children learn?

- How does the educator help the children who are dual language learners in her class?

- What skills are children building that will help them learn to read?

Video Debrief

What tools does the educator use to help all children and what skills are they building that will help them to read? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Tools the educator uses are:

- Phonological awareness

- Dual language strategies

- Engaging children’s interests

- Encouraging children’s bodies to move (clapping)

To help the dual language learners in her class, the educator substitutes some words in Spanish to ensure that children understand them.

The children are building syllable and phonological awareness that will help them recognize the letters in words that make up the sounds they hear in their heads as they say words.

B – Print and Alphabet Knowledge

The Print and Alphabet Knowledge subdomain encompasses the skills that are important for understanding written language. For example, some of these are: understanding how print is used (its functions) and the ability to identify letters of the alphabet and to match or produce the sounds that go with each letter.

Between 3 and 4 years of age, children develop an awareness that text means something. They are able to tell the difference between pictures in a book and printed text, and they will ask questions about it such as, “What does this say?” or “Read this to me?”

They also begin to identify letters in the alphabet as a symbol system and are learning that letters correspond to sounds they know. For example, they may sing the ABC song and be able to recognize the letters in their name, or some of the more common letters.

Learning about Print

As we just discussed, children’s print and alphabet skills grow between 4 and 5 years of age.

By age 5, most children should be able to name 18 uppercase and 15 lowercase letters and know sounds associated with several letters.

Throughout this period, children continue to develop a more nuanced understanding of print, including some knowledge that print has rules. For example, in English, we read from left to right. They also learn that words are made up of groups of letters.

And by age 5, children begin to practice reading by reciting simple memorized texts and they can identify single-syllable words from a story.

Interactive: Learning About Letters

Interactive: Learning About Letters

Between the ages of 3 and 7, children learn to name, print, and produce letter sounds.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to build alphabet knowledge with young children.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Playtime Picks

Pick a color or letter with your child and, together, go on a scavenger hunt to find as many things as you can in three minutes. How many things in the house are blue? Count out loud together as you find each item. You can also play with letters: How many things do you see that start with the letter T?

Ages 4-5

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

“I Spy” games like this one are great brain builders. They make your child aware of his/her environment and teach him/her to make connections between similar things. You can try this game with letters, colors, shapes – anything really!

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit?

C – Comprehension and Text Structure

Between 3 and 4 years of age, children are also building their understanding of narrative structure, or how stories are built and told.

They begin to ask and answer questions about books that are read aloud. These skills fall under the subdomain Comprehension and Text Structure. These skills are built by listening to and acting out stories. As children listen to stories and answer questions about them, they learn to identify different narrative elements.

One way to help build children’s understanding of narrative is for children to act out stories using pictures or props, which they are able to do between 3 and 4 years old. After listening to a story, children of this age may be able to retell one or two elements.

Children are also able to answer simple questions about the story and even ask questions of their own. Educators can support children in thinking about what might happen next or making predictions about the story they are reading.

Narrative Skill-Building

Between 4 and 5 years of age, children build their narrative skills. They are able to retell more key events (two to three) and are able to put those events in the right order.

Children’s ability to create stories also emerges in this period, and by the time they are 5, they can tell personal stories or stories they made up that have two to three connected events. With support, they are also able to answer more and more complex questions about stories, including making predictions and explaining why or how something happened in a story.

By age 5, children are even able to guess what characters in the story might be feeling or what their intentions are based on. These complex skills involve other cognitive skills as well, including memory and problem solving, as well as social and emotional skills, like being able to recognize emotions in others.

Narrative Complexity

Children’s narrative skills grow significantly during their preschool years. Research indicates that between 40 and 70 months (3 years, 4 months and 5 years, 10 months), children’s narrative becomes more complex, more coherent, and more detailed. For example, children’s narrative about the same event in their life becomes more elaborate and complex.

Researchers have investigated children’s narrative development using several different measures.

Interactive: Narrative Complexity

Interactive: Narrative Complexity

This is an interactive! Use the slider in the interactive to explore the graph.

While children’s narrative is developing in all of these areas, children’s use of evaluative, or interpretative, information is not as frequent as their use of orientating information or referential information about actions.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to build narrative skills and vocabulary with young children.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Daily Do-Over

Bedtime is a great time to look back on all the fun you and your child packed into the day. So tonight, ask your child what his/her favorite parts of his/her day were – like stepping in a puddle or popping bubbles at bath time. Then share yours with your child – he/she will love hearing about your day!

Ages 4-5

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

By reflecting on your day together, you are helping your child build his/her vocabulary and memory skills. And by sharing an event from your day you are giving your child a peek into the world of adults.

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit?

Writing

Writing is the final Literacy subdomain. During this period in development, children begin to use writing for many different purposes and use more and more complex marks.

Between 3 and 4 years of age, children’s writing is mostly scribbling and drawing. They use their drawing and scribbling to share meaning and sometimes the drawings may contain forms that look similar to letters.

Between 4 and 5 years, children will increasingly use their drawing and scribbling to convey more complex meanings, including letters that also have meaning. This development is linked to their narrative skills that are also growing at this time, as we just discussed.

Children also show increasing interest in written text, such as wanting to copy words that they see written around them or trying out their spelling skills by perhaps getting the first letter in a word correct and filling the rest in with invented spelling.

References

References

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Berko, J., & Brown, R. (1960). Psycholinguistic research methods. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in child development (pp. 517–557). Wiley.

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). Tapping syllables. University of Washington. [Video File]

Fivush, R., Haden, C., & Adam, S. (1995). Structure and coherence of preschoolers’ personal narratives over time: Implications for childhood amnesia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 60(1), 32–56.

Sander, E. (1972). When are speech sounds learned? The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 37(1), 55–63.

Wandell, B. A., Rauschecker, A. M., & Yeatman, J. D. (2012). Learning to see words. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 31–53.

Worden, P. E., & Boettcher, W. (1990). Young children’s acquisition of alphabet knowledge. Journal of Literacy Research, 22(3), 277–295.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages birth to five. [Website]

Vroom (2017). Tools and activities. [Website]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 5-2 Literacy. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]