12-3 Screens and Young Children

A – Screens and Young Children

Screens are increasingly a presence in children’s lives, particularly since children’s families are using screens. So it’s important content to consider as we think about children’s development in the context of the family.

The most recent screen-use data indicates that children have access to screens everywhere.

- Children birth to age 8 spend almost 2 hours with screen media per day.

- 36% of parents report that the television is on all or most of the time at home.

- 72% of children have used mobile media, such as tablets and smartphones.

- 58% of parents have downloaded an app for their child.

- 27% of screen media exposure is with computers, tablets, and cell phones.

American Academy of Pediatrics

To guide parents’ and caregivers’ thinking, the American Academy of Pediatrics has made recommendations for children and screens.

The latest guide, released in 2016, makes these recommendations:

- Children younger than 18 months should avoid screen time, except video chats.

- For children from 18 months to 5 years, parents should choose high-quality programming and interact with children around the screen to help them understand the content.

Two additional recommendations are:

- For children older than 6 years, parents should set limits on the use of screens and the type of screens and parents should make sure that screens do not replace other critical activities for children like sleeping or playing outside.

- Parents should designate screen-free times and locations, such as meal times and bedrooms.

In the rest of this section, we’ll briefly explore some of the research that guided the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this topic.

Reflection Point

Use these questions to discuss the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations about screen time:

- Did you know that the American Academy of Pediatrics has guidelines about screen time?

- What parts of these guidelines will be easier or more challenging for families to implement?

B – The Video Deficit Effect

Lots of research has demonstrated that children learn better from live interactions than they do from screen media, an effect known as the video deficit. Even when children are capable of learning something from video, research typically shows that children learn better and faster through live interactions. This trend continues through childhood.

We talked about one example in lesson 4 on early language development. When 9-month-old children listened to a native Mandarin speaker in person, they learned the sounds of Mandarin, but when they heard the same speaker on DVD or audio CD, they showed no evidence of learning.

Other research examined infants’ ability to imitate actions they saw demonstrated in person or on video. Both the in-person and video groups imitated the action, but the group who was learning from the video required double the number of demonstrations before they could imitate from video. These 1- to 2-year-olds learned much faster from the live person.

One final example looked at children’s ability to learn words from videos or a combination of videos and live interactions. Children younger than 3 years were unable to learn from the video by itself, but they did learn new words when they interacted with an adult around the screen. The adult demonstrated the actions on the screen, labeled things, and provided the child with social interaction.

Although children older than 3 years were able to learn words from the video alone, they did not show the same depth of learning as children who had the adult interaction in addition to the video. Children learned better when they could interact with an adult in addition to watching the video.

Video Chats

While research indicates that children seem to learn from screens differently than they learn from live interactions, there is one exception—video chat.

Video chat is an interesting exception to screen time and one that the American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledged in their recommendations because even though children are using a screen, video-chat technology allows children to experience a live interaction with the person on the other side of the screen.

When children use video chats, they engage a genuine back-and-forth interaction with the person on the other side of the screen. The person can talk to them and respond accurately to them. Eye gaze across video chats is imperfect because of the relative positions of the screen and the camera, but video chats have many of the other elements that researchers think are critical to children’s ability to learn from live interactions.

Indeed, children seem to learn from video chats just like they learn from live interactions. Researchers taught children new words either through video, video chat, or live interactions. Two-year-olds learned the novel words from video chat just like they did from the live interactions. They did not learn from the video. This supports the idea that video chats should not be placed in the same screen category as traditional video.

Talking Toys

As we start to think about what interacting with a child looks like, a recent study tells us a little bit about what it’s not.

Professor Anna Sosa at Northern Arizona University was interested in talking toys—toys that label objects. This particular study used a talking farm, a baby cellphone, and a baby laptop. The researcher looked at parent-child interactions while children were playing with one of the talking toys.

Sosa found that when a child was playing with the talking toy, parents said fewer words and fewer content-specific words. Children also used fewer words, and the parent and child had less back-and-forth interaction.

The researcher noted that when something else, such as a toy, was doing the talking, parents seemed to let toy talk and respond for them. In essence, it’s as if the talking toy turns off the parent-child interaction.

The talking toy, although using words and making noises, cannot take the place of a real-life social interaction for children. The toy isn’t social, the parent is. This is important as we start to think about optimal parent-child interactions around technology.

Scaffolding

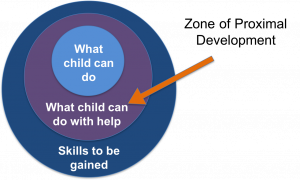

As we discussed in lesson 1, the psychologist Vygotsky talked about the Zone of Proximal Development. This zone of children’s knowledge represents skills that children can do or learn with help. In this zone, older or more capable people can help children acquire new skills by pushing them beyond their natural boundaries and therefore expanding their knowledge.

When adults support children this way, it is called scaffolding. Scaffolding is critically important to children’s ability to learn from screen media. Adults can help children:

- Make sense of the two-dimensional world of screens and draw parallels to the real world. For example, adults might say, “Do you see the dog on the screen? That’s just like Fido in our house. The dog on the screen is brown, and Fido is brown, too. Do you think the dog on the screen likes bones as much as Fido does?”

- Understand content by explaining new vocabulary words, helping children understand the actions of characters, or answering children’s questions.

- Navigate the fine-motor tasks related to technology. Computer mice are particularly difficult to operate.

Media Scaffolding

We’ll use the content from the next two videos to discuss scaffolding around media. While watching the videos, consider: What do you notice about how the educators scaffold children’s media use?

Video: Your Turn (0:12)

This video called Your Turn, shows an educator scaffolding content and turn-taking around a tablet.

Video: Restarting the Computer (1:59)

The video, Restarting the Computer, shows an educator scaffolding the technical aspects of using a computer, such as restarting and waiting for it to reboot.

Video Debrief

What did you notice about how the educators scaffolded children’s media use? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answer

We considered the following possible answers:

- Counted to help a child wait while the computer rebooted.

- Talked about what to expect with the computer restart, saying, “You’ll see a black screen.”

- Prompted turn-taking with the tablet in a rehearsed answer.

Next, think of at least two more techniques you might use to scaffold children’s media use. Think of one strategy to help children with the technology and one to scaffold content. Your ideas will depend on your own experiences, but possible answers are:

- Use pictures with steps showing how to use computers and tablets.

- Have an adult model use of the computer when introducing the computer area.

- Provide a sign-in chart.

- Have educational games, apps, and web pages preloaded and easy to access.

Reflection Point

Use these questions to review.

- What are two recommendations the American Academy of Pediatrics makes for screen media and children?

- Why is scaffolding screen media important for children’s learning?

C – Technology In Adult Lives

Just as technology is increasingly present in children’s lives, technology is also present in the lives of parents. Researchers have been curious about how adult use of technology affects children’s development.

In general, new research finds that when parents use digital technology around children, the quality and quantity of parent-child interactions decreases. Specifically, there are fewer parent-child interactions overall and lower responsivity to children’s bids for attention when parents use mobile technology in front of children. Some research has even suggested that parents respond to children with more hostility when the child interrupts their use of technology.

To the extent that children model their actions after the actions they see, children are also forming norms about how and when to use technology by watching their parents. In sum, when we think about the effect of screens on children’s development, we need to consider parents’ use of technology in addition to children’s use of technology.

Learning From Screens

Increasingly, researchers are beginning to understand that children learn from screens in the same way they learn in other contexts.

That is, children learn:

- When they are actively involved.

- When they are engaged.

- In socially interactive contexts.

- When the content is meaningful.

Using these principles, we can understand why technologies like video chat work so well—it satisfies all of these criteria! Similarly, when adults scaffold children’s media experiences, they create the ideal scenario for children’s learning.

Being able to develop abstract principles like these is helpful because research cannot keep up with new technologies, much less with particular apps and programs. These principles can help us evaluate new technologies and create quality learning experiences for children.

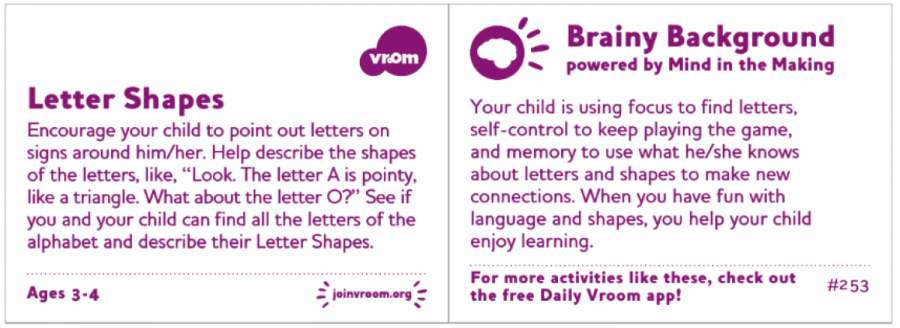

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to support young children’s development. These same kinds of questions can be used to guide adult interactions with children around screens.

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? If not, how will you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Letter Shapes

Encourage your child to point out letters on signs around him/her. Help describe the shapes of the letters, like, “Look. The letter A is pointy, like a triangle. What about the letter O?” See if you and your child can find all the letters of the alphabet and describe their Letter Shapes.

Ages 3-4

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

Your child is using focus to find letters, self-control to keep playing the game, and memory to use what he/she knows about letters and shapes to make new connections. When you have fun with language and shapes, you help your child enjoy learning.

References

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016, October 21). American Academy of Pediatrics announces new recommendations for children’s media use. [Online Article]

Anderson, D.R., and Pempek, T.A. (2005). Television and very young children. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(5). [Online Article]

Barr, R., Muentener, P., Garcia, A., Fujimoto, M., & Chavez, V. (2007). The effect of repetition on imitation from television during infancy. Developmental Psychobiology, 49(2), 196-207.

Common Sense Media. (2013, October 27). Zero to eight: Children’s media use in America 2013. [Online Article]

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). Restarting the computer. University of Washington. [Video File]

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). Your turn. University of Washington. [Video File]

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Zosh, J. M., Golinkoff, R. M., Gray, J. A., Robb, M. B., & Kaufmann, J. (2015). Putting education in “educational” apps: Lessons from the science of learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(1), 3-34.

Hiniker, A., Sobel, K., Suh, H., Sung, Y. C., Lee, C. P., & Kientz, J. A. (2015). Texting while parenting: How adults use mobile phones while caring for children at the playground. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings. (Vol. 2015-April, pp. 727-736). Association for Computing Machinery.

Lerner, C. (2014). Screen sense. Zero to Three. [Online Resource]

Lauricella, A. R., Pempek, T. A., Barr, R., & Calvert, S. L. (2010). Contingent computer interactions for young children’s object retrieval success. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(5), 362-369.

Preissler, M.A., & Bloom, P. (2007). Two-year-olds appreciate the dual nature of pictures. Psychological Science, 18(1), 1-2.

Radesky, J., Miller, A. L., Rosenblum, K. L., Appugliese, D., Kaciroti N., & Lumeng, J. C. (2015). Maternal mobile device use during a structured parent-child interaction task. Academic Pediatrics, 15(2), 238-244.

Radesky, J. S., Kistin, C. J., Zuckerman, B., Nitzberg, K., Gross, J., Kaplan-Sanoff, M., Agustyn, M., & Silverstein, M. (2014). Patterns of mobile device use by caregivers and children during meals in fast food restaurants. Pediatrics, 133(4), 843-849.

Roseberry, S., Parish-Morris, J., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R.M. (2009). Live action: Can young children learn verbs from video? Child Development, 80(5), 1360-1375.

Roseberry, S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R.M. (2014). Skype me! Socially contingent interactions help toddlers learn language. Child Development, 85(3), 956-970.

Sosa, A.V. (2016). Association of the type of toy used during play with the quantity and quality of parent-infant communication. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(2), 132-137.

Turner, C. (2016, January 11). The trouble with talking toys. NPR. [News Article]

Vroom. (n.d). Vroom tips. [PDF]

Zosh, J., Lytle, R. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2017). Putting the education back in educational apps: How content and context interact to promote learning. In R. Barr & D. Linebarger (Eds.), Media Exposure During Infancy and Early Childhood (pp. 259-282). Springer.

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 12-3 Screens and young children. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]