7-3 Supporting Preschooler Social and Emotional Development

A – Supporting Early Development

Much like the subdomain headings, many of the same supports that were effective for infant and toddler social and emotional development continue to be effective for preschoolers. They just begin to look different. These are:

- Responsiveness and contingency (how you, as an adult, respond to the child)

- Modeling (actions and interventions)

- Emotional literacy (recognizing and labeling emotions in others and oneself)

However, we will add one area of support. That is play.

As mentioned earlier in this session, pretend play in preschoolers is a fertile environment for the development of social and emotional skills.

We’ll now cover examples of support for preschoolers’ social and emotional development in each of these areas.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness is a critical way in which caregiving adults can teach children social and emotional skills. There is good evidence that young children who have warm relationships and secure attachments to their parents are more likely to be empathic and prosocial.

One way in which they might do this is by noticing and copying the behavior of adults to whom they feel a close connection.

It is important to remember that all caregiving adults play a role.

In one German study, preschoolers’ social and emotional adjustment was measured along with their interactions with their fathers. And researchers found that fathers’ sensitive, challenging play with preschoolers predicted favorable emotional and social adjustment.

By responding to preschoolers’ cues compassionately and sensitively, you are teaching them both that their voice matters and that it is important to treat others in this way.

Children who are neglected are much more likely to neglect others in turn. They have learned that this is the way others should be treated.

Even one safe, responsive relationship can help provide children with a different social model to use in their own relationships.

Modeling Behavior

Modeling relationships with other people also is important for social and emotional development. Preschool children are looking to the adults in their lives for information about social rules and models for how to interact with others.

Everyone experiences negative emotions sometimes. Preschoolers are watching you, as an adult, intently to find out how to deal with those negative emotions. Consider these questions:

- How does the adult react when they break something they didn’t mean to break?

- How does the adult react when their friend looks sad or someone gets hurt?

Watching adults in these situations gives children an idea of what they can do as well. Have you ever noticed a child copy someone’s unique reactions to a situation? For example, if a child’s parent often says, “Oh goodness,” when something goes wrong, you may often hear the same phrase from the child when they are frustrated or someone is sad.

For example, in one study, researchers found that children pay attention to how their parents resolve conflict. If parents were able to resolve their conflict with a compromise, children actually felt positive emotions after the negative emotional event.

Scaffolding Social Problem-Solving

Scaffolding is another way that adults can help children build social skills. Remember that despite their developmental leaps and bounds, preschoolers are still building their social skill toolbox.

If you see a child navigating a social problem, maybe the child accidentally broke a friend’s tower and is experiencing difficult emotions, it might be a good time to step in and make some suggestions. Ask the child if it was an accident or if they mean to do it. And if it was an accident, prompt them to figure out a solution: “Hmm… What could you do to help your friend feel better?”

See if the child can come up with an idea, and if not, offer a couple possibilities. In the future, the child can draw from this experience and try the same solutions when new social problems occur.

Emotional Literacy

Adults can also scaffold children’s emotional literacy. The more that adults label and explain emotions with preschoolers, the better developed their emotional understanding is.

For preschoolers, expanding their overall vocabulary, books on emotions, and emotion-labeling activities are ways to support children’s emotional literacy. Playing games, such as emotion charades, is an engaging way to do this in an early learning environment. Either the educator, or the children themselves, depending on their age, can show an emotional expression and see if the other children can guess what emotion they are expressing. Or, children can draw pictures of people with different emotions and then talk about what each emotion feels like or times when they felt those emotions.

Another way to expand children’s emotion literacy is for adults to label their own emotions when they occur. If you trip and fall, you could explain that you feel, embarrassed, hurt, angry, or sad. And then you can also explain what might make you feel better—a hug, an ice pack, a song, or any number of solutions. This will help children see in which contexts different emotions occur so that they can better recognize those same emotions in themselves.

There are also songs and videos of characters feeling different emotions that, when combined with adult engagement, can help children learn more about emotional literacy. Any activity that helps children expand their emotion vocabulary and categorize different kinds of emotions will help support their emotional literacy.

B – Social Benefits of Play

Play offers a myriad of opportunities for children to practice social skills and communication, build relationships, and to try things out in a safe, protected way.

Children learn from playing with other people about how to take turns and how to manage and express emotions. Many children use pretend play with their toys to explore social situations. Emotion talk can be particularly rich during this kind of pretend play. This contributes to children’s emotional understanding and the development of positive relations with their peers.

When preschool-age children engage in dramatic play, they also learn how to take others’ perspectives and practice communicating thoughts and feelings. Through these activities, differences of opinion or planning will arise. These provide moments when children learn how solve social problems.

A variety of social skills develop from these interactions:

- Children can use words to describe others’ feelings.

- They can take turns.

- They can demonstrate control over their actions.

- They can demonstrate prosocial behaviors.

- They can resolve conflicts.

Several studies have even shown that toddlers and preschoolers who demonstrated prosocial attitudes and behaviors during play were more likely to make new friends, be accepted by their peers, and form secure relationships with educators. This, in turn, is predictive of later achievement.

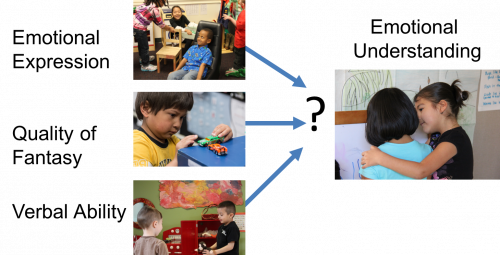

Researchers have even found a high correlation between children’s ability to create fantasy during play and their emotional understanding.

Building Emotional Understanding

In one study, children were asked to play on their own with two puppets and some blocks any way they wanted to for 5 minutes. Children’s fantasy play during this time was evaluated for two elements:

- Their emotional expression with the toys

- The quality of their fantasy play, or how elaborate, organized and imaginative their fantasy play was

In a second part of the study, children’s verbal ability was assessed.

Finally, the children were interviewed by a researcher and asked about their emotion understanding. The researchers wanted to know which of the children’s skills were most strongly linked to their emotional understanding. Was it the quality of their fantasy play, their emotional expression during play, or their verbal ability?

Play and Emotional Understanding

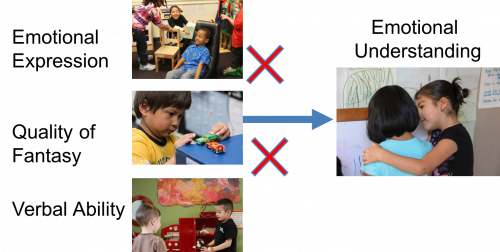

Researchers found that a child’s emotional understanding was most strongly linked to the quality of their play, rather than their verbal ability or emotional expression.

This means that even if a child isn’t able to verbally produce words about emotions or isn’t motivated to express emotions during playtime with their toys, that child might still have a high level of emotional understanding. It also means that the quality of play during an activity is a better window into a child’s emotional development than either verbal ability or expression of emotional content during play.

This is important to note, because as adults we often use verbal ability as a way of assessing a child’s competence on a particular topic. In the case of emotional understanding, research suggests that this may not be the best measure to use.

Play to Support Development

One way to support development through play is to provide materials that encourage social play. Providing cooperative play materials, such as tea sets, costumes for role-play, train sets, or turn-taking games are ways of encouraging children to socialize during playtime.

Sometimes, children may need help with prosocial engagement. For example, two children could be focused on pouring and drinking tea. Another child is nearby but not yet part of the game. You could ask if there is any food to go along with their tea or if someone could bake something to go along with their tea.

You can also model and facilitate open-ended discussion of social knowledge by asking questions about preferences, likes, and dislikes. For example, you could ask the children if the tea tastes good or if it’s too cold or hot. Disagreements during play can be an opportunity to support children in learning the first steps to thinking of others’ perspectives.

Modeling how to do this by verbalizing what another child might be feeling, and talking children through the process can help support their learning.

Emotion Regulation Strategies

Another way to support children’s social and emotional development is to help them develop strategies for emotion regulation.

Next, you’ll watch two videos with two different ways to support children’s emotion regulation.

As you watch the following videos, consider:

- What are the pros and the cons of each approach to supporting emotion regulation?

- Which methods do you prefer and why?

Video: Helping Toddlers Regulate Emotions (4:53)

This Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence video focuses on helping toddlers regulate their emotions using the RULER method. RULER is an acronym that stands for recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing, and regulating emotions.

Watch Helping Toddlers Regulate Emotions from Yale University on YouTube.

Video: 6 Tips To Help Your Children Control Their Emotions (2:40)

UCLA Health’s 6 Tips to Help Your Children Control Their Emotions video is on helping toddlers regulate their emotions.

Watch 6 Tips to Help Your Children Control Their Emotions from UCLA Health on YouTube.

The two videos you just watched present a variety of ways to support children’s emotion regulation.

After watching the videos, think about the following questions:

- What are the pros and cons of each method?

- Which methods do you prefer and why?

References

References

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Campbell, S. B., & von Stauffenberg, C. (2008). Child characteristics and family processes that predict behavioral readiness for school. In Disparities in School Readiness: How Families Contribute to Transitions into School (223-258). Taylor and Francis.

Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning. (n.d.). What works brief: Fostering emotional literacy in young children. [Website]

Kestenbaum, R., Farber, E. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1989). Individual differences in empathy among preschoolers: Relation to attachment history. New Directions for Children and Adolescent Development, 1989(44), 51-64.

Seja, A. L., & Russ, S. W. (1999). Children’s fantasy play and emotional understanding. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28(2), 269-277.

UCLA Health. (2016, July 6). 6 tips to help your children control their emotions. [Video]

Yale University. (2016, June 1). Helping toddlers regulate emotions. [Video]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 7-3 Supporting preschooler social and emotional development. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]