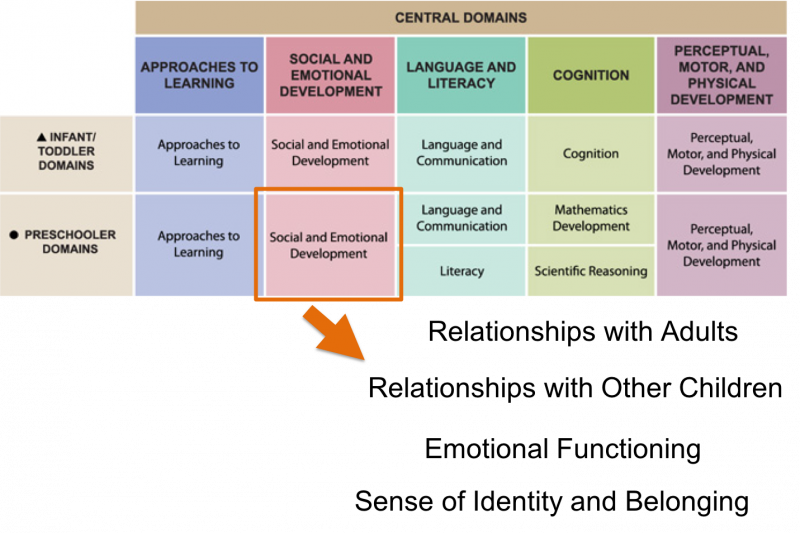

7-1 Preschool Social and Emotional Development

A – Social and Emotional Development Domain

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework

The framework’s preschool Social and Emotional Development domain includes the same four subdomains as for infants and toddlers:

- Relationships with Adults

- Relationships with Other Children

- Emotional Functioning

- Sense of Identity and Belonging

However, the balance between the subdomains is substantially different for preschoolers than it was for younger children.

Remember, the focus in infant and toddler development is on relationships with adults and developing the ability to distinguish oneself from other people. Preschoolers are expanding on those skills by developing lasting relationships with other children and establishing their own social identity.

So even though the preschool subdomains for Social and Emotional Development have the same names as those for younger children, the content of those subdomains is significantly different.

The preschooler subdomains also include the development of more mature social skills, such as:

- Offering support and making empathic statements to other children and adults.

- Developing friendships with other children.

- Asking for adult permission before doing something of which children are unsure.

B – Relationships with Adults

Prosocial Engagement

The first subdomain focuses on children’s developing relationships with adults.

As infants and toddlers, children may be upset by the expression of negative emotions in others, but it isn’t until later in the second year or early in the third year of life that children regularly take action to alleviate those negative emotions in others.

Voluntary actions that benefit others are called prosocial behaviors, such as helping, comforting, and sharing. Prosocial behaviors may seem routine and automatic to us as adults, but for children they require solving a complex puzzle of social information.

First, the child has to recognize that another person is experiencing a negative emotion based on a need, a distressing situation, or a desire. Then, they have to figure out what behavior might be effective at alleviating the other person’s need, desire, or distress. Finally, they have to motivate themselves to perform the prosocial act.

Children as young as 2 years old have begun to perform prosocial acts in response to the obvious needs of an adult. For example, an adult may drop a puzzle piece and need help picking it up. And they can do this even if the adult never directly requests help.

By 3 to 4 years of age, children consistently respond with prosocial behaviors to another person’s obvious emotional distress. For example, an adult may hurt themselves or feel sad when a toy breaks.

Interestingly, however, 3- to 4-year-old children are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior when they can respond to another person’s distress with an action, such as fixing a broken toy, than when they have to provide purely emotional comfort, such as a hug when a person is hurt.

The one context in which even 4-year-old children still struggle is in figuring out when another person desires something but does not ask for it directly. For example, if someone gives a child a bowl full of strawberries and an adult an empty bowl, that child is unlikely to think of sharing their strawberries with the adult unless the adult explicitly asks for strawberries from the child’s bowl.

Admittedly, this is a complex concept to figure out. But it is important to note that even preschool-age children might not distribute resources spontaneously unless prompted to by a request. And this is not necessarily a failure of sharing or kindness but in fact an inability to read the social cues expressed by another person about desire or to note inequalities on their own.

Social Norms

Preschoolers are also beginning to notice social norms or the way things are usually done in their society and culture.

Just as infants and toddlers reference adults for social information—remember the visual cliff social referencing study with infants—preschoolers reference adults for information about social norms.

In fact, scientists have found that even children as young as 3 years old will assume that an action is normative (or the usual way of doing things) even when an adult doesn’t give them any obvious social cues that this is the case.

Instead, children appear to use an adult’s intentions as the primary sign of whether an action is being done in the usual manner or not. For example, if an adult looks like they recognize an object and know exactly what to do with it, children will assume that this is the way to use this object. If instead an adult looks like they have no idea what the new object is and plays around with it first before deciding what to do with it, children do not assume that this is necessarily the way to use this object.

Children will make these normative assumptions about adult actions and behaviors even when the adult never looks at the child or in any way directs their behavior toward the child.

Trusting Adults

Preschoolers also are expanding their circle of trust and sources of information. They will use information from unfamiliar adults over familiar ones, depending on their respective reliability and accuracy.

Scientists studied this by asking 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds questions about information provided either by a familiar educator or an unfamiliar one. Initially, all children regardless of age, preferred to use information from the familiar educator over information from the unfamiliar educator, just as infants and toddlers do.

Children then watched as both educators named a set of objects familiar to the children. The unfamiliar educator always named the objects correctly, while the familiar educator never did.

After watching the unfamiliar educator consistently succeed and the familiar educator consistently fail to provide accurate information, 4- and 5-year-olds were less likely to trust subsequent information provided by the familiar educator.

This means that even though the 4- and 5-year-olds generally preferred the familiar educator, they were able to evaluate the educator’s accuracy and change their reliance on the familiar educator’s information for future questions.

Notably, 3-year-olds were not affected by the familiar educator’s inaccuracies. They continued to prefer the information from the familiar adult over that of the unfamiliar adult.

The ability to combine familiarity and reliability when evaluating adults as sources of information appears to develop around 3 to 4 years of age.

Video: From Feelings to Friendships (5:32)

This video From Feelings to Friendships: Nurturing Healthy Social-Emotional Development in the Early Years covers adult-infant relationships and then peer-to-peer relationships, including empathy and social expectations. It helps to bridge the connection between relationships with adults and relationships with children.

As you watch this video, consider:

- How do children communicate their needs?

- How do you soothe children who are crying?

- What do you do to help children express emotions appropriately?

- How do you help children you work with develop empathy?

These discussion questions are adapted from the Zero To Three tip sheet, Magic of Everyday Moments: From Feelings to Friendships, that accompanies the video From Feelings to Friendships: Nurturing Health Social-Emotional Development in the Early Years.

Watch From Feelings to Friendships from ZEROTOTHREE on Vimeo.

C – Relationships with Other Children

Friendships

By the time children have reached preschool age, they find their peer groups more interesting than the adults in their lives. The second Social and Emotional Development subdomain, Relationships with Other Children, characterizes children’s development in this area.

Children can form rudimentary friendships starting in the second year of life, but those relationships are increasingly more complex as children mature in the preschool years. Initially, friendships primarily consist of a preference for a particular individual and eventually develop into reciprocal social relationships.

Preschoolers are more likely to forgive transgressions committed by established friends than those committed by other individuals. And the relationships they build with their peers, even in early childhood, can help protect children against developmentally disruptive factors in their lives. For example, peer social relationships can be a source of emotional security for some children. Social and emotional competence is key to the formation of these relationships, both at the group and individual levels.

But how do children go about establishing friendships? First, children need to develop the ability to regulate their own gaze to visually engage another individual and to use clear communicative gestures and words. These skills are particularly important when a child is in a group setting and miscommunications can easily occur.

Emotion regulation and action inhibition are also key components to the development of friendships. These allow children to not only understand others’ personal boundaries and to keep calm despite a friend’s distress but to also respect those boundaries and provide emotional support when possible.

Social Strategies

Preschoolers begin to use their new social and emotional skills to develop strategies for engaging social partners. For example, they begin to demonstrate spontaneous sharing and improved turn-taking skills.

Children who are 3 to 5 years old are also developing the ability to keep track of social history. They are more likely to share with individuals with whom they collaborated or shared with successfully in the past.

They can then use this history to select social strategies when engaging with others. Over the course of the preschool years, scientists find that children are increasingly more selective in how, when, and with whom they share resources.

But it takes two people to share, and scientists conducted an interesting study investigating the other side of the sharing equation: what children expect other people’s sharing behavior to look like. They asked 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children about sharing between two characters and what they found was that children at all ages expected both characters to share with each other when sharing bore no cost to either character.

When the sharing was costly, 5-year-olds demonstrated a clear preference for sharing with friends rather than peers they disliked.

Three-year-olds, on the other hand, seemed to expect everyone to share with everyone else regardless of the cost or who the other person was.

In addition, 5-year-old children appeared to adhere to the old adage of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Their expectations of others’ sharing behavior matched their own sharing behavior on an individual level, while 3- and 4-year-old children did not show the same consistency between their own sharing behavior and their expectations of others’ sharing behaviors on an individual level.

The picture that emerges is that by 3 years, children have strong prosocial expectations for behavior between people. As children mature, they are more selective in their expectations. By 5 years, children have different expectations for friends than they do for others.

Video: Kids Talk: Making Friends (0:49)

This video is Sesame Street’s Kids Talk: Making Friends. In this video, pairs of children of various ages in preschool and early school years talk about what friendship means to them.

Watch Kids Talk: Making Friends from Sesame Street on YouTube.

Video Debrief

After watching the video, consider these questions:

- What does friendship mean to you?

- What does friendship mean to the children with whom you work? How do they form friendships?

- How might you encourage children’s friendships?

These questions are meant to inspire you to explore you own concepts of friendship and what that means to children.

D – More Relationships with Other Children

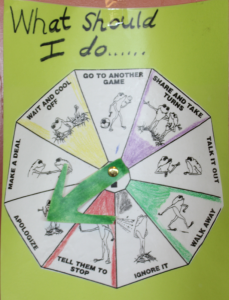

Social Problem-Solving

Between the ages of 3 and 5, preschoolers develop the complex communication skills necessary to establish cooperative interactions with other children, such as the creation of joint goals.

Social problem-solving is another aspect of social and emotional development that blossoms in the preschool years. Children at this age are increasingly able to predict other people’s future behavior. For example, 4-year-olds know that an angry child might hit someone and that a happy child is more likely to share.

Preschoolers will also come up with ways to reduce other’s distress, such as hugging. These are all components of social problem-solving.

Social problem-solving works best when a child is able to note when a social problem has occurred, clearly and calmly express their own emotions, and seek a resolution.

Researchers agree that cooperative social interactions that require social problem-solving are essential to both social and cognitive development. They have proposed that one of the critical components of cooperative social interactions is establishing joint engagement in a task. When working together, children have to figure out joint goals, the steps needed to achieve those goals, and resolve any ensuing social conflicts.

These steps require mature communication skills. Children have to begin to understand each other’s intentions and beliefs and have to be able to flexibly adapt to another person’s behavior. Preschoolers are beginning to do this in increasingly complex situations.

However, social problem-solving is still a challenging area of development for most preschool-age children. The difficulty of the task in particular can greatly affect the social learning benefits that children experience when completing a cooperative task and tackling social problem-solving.

When scientists compared 5-year-olds’ cooperative interactions when solving an easy puzzle together to their interactions when solving a hard puzzle together, they found that children were more cooperative, more successful, and more engaged when working together on the easy task than on the hard task.

It appears that on harder tasks, young children have a difficult time establishing joint goals. In addition, it is important to consider that when a social problem is too emotionally stressful, it can adversely affect children’s learning in that situation.

Social Play

One context in which children greatly benefit and excel at social problem-solving is pretend play. Pretend play is found to increase in both frequency and complexity between 3 and 5 years of age across cultures.

Children’s ability to demonstrate cooperative problem-solving during pretend play surpasses their ability to do so in more traditional experimental, cooperative problem-solving tasks.

This may be the case because of the unique characteristics of play interactions. Play interactions are, by definition, familiar, safe, comfortable, and highly motivating. In contrast, experimental cooperative tasks are often novel, unfamiliar, and not usually as highly motivating.

Encouraging children’s cooperative pretend play and creating environments that promote these social interactions are ways to increase children’s opportunities for social development.

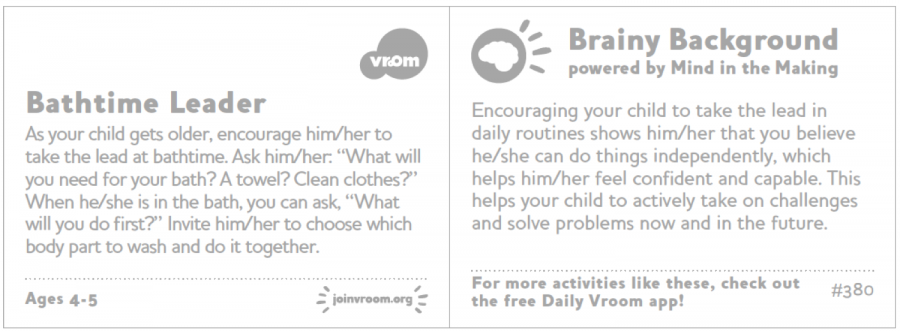

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to help build children’s social and emotional development.

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Bathtime Leader

As your child gets older, encourage him/her to take the lead at bathtime. Ask him/her: “What will you need for your bath? A towel? Clean clothes?” When he/she is in the bath, you can ask, “What will you do first?” Invite him/her to choose which body part to wash and do it together.

Ages 4-5

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

Encouraging your child to take the lead in daily routines shows him/her that you believe he/she can do things independently, which helps him/her feel confident and capable. This helps your child to actively take on challenges and solve problems now and in the future.

E – Emotional Functioning

Emotional Literacy

Children’s ability to regulate and express emotions becomes more and more critical to their social and emotional development as they mature.

Emotional literacy is a key component of children’s developing emotional competence. By labeling emotions, children can enhance their emotion recognition, application of emotion-regulation strategies, and social problem-solving skills.

However, children do not automatically label their own or other’s emotion and can often confuse emotional terms. Adults can help children by encouraging them to label emotions with words and by showing them how to use emotion vocabulary in context.

It is also during this time that children begin to conform to emotional display rules and may even enforce them in others.

Emotional literacy, like other areas of language development, grows exponentially during this time. By the end of the third year of life, most children are able to use words for emotions, such as loving, mean, and surprised. By the time they are 5 years old, their emotional vocabulary may have grown into the hundreds.

Theory of Mind

By 5 years of age, children begin to describe how other people feel and have begun to develop self-conscious emotions, such as shame and pride.

Being able to recognize others’ emotions as different from one’s own and understanding self-conscious emotions requires an understanding of theory of mind: the understanding that other people can have feelings, emotions, and beliefs separate from our own.

While this is still a very active field of investigation for developmental psychologists, scientists agree that by 3 years of age most children have begun to develop a theory of mind and the ability to take others’ perspectives. And by the time children are 5 years old, they will spontaneously recognize emotions in other people and attempt to explain them.

The development of theory of mind is critical to social and emotional development. Being able to acknowledge and empathize with another person’s emotions is crucial for the development of empathy. When children understand the emotion that another person is experiencing, they can apply their own experiences to connect and provide support to that person.

Following Eye Gaze

Between 3 and 5 years, children develop an understanding of theory of mind, or the idea that others have beliefs and desires different from their own. One way scientists believe that children develop theory of mind is by using other people’s eye gaze to determine what they are thinking.

If you offer someone pretzels or peanuts and they stare at the bowl of pretzels, you would probably think that they want the pretzels more than the peanuts. We know that by preschool, children can also use other people’s eye gaze to figure out what they want.

There is even evidence that infants, who are better at gaze-following at 10-and-a-half months, might also be better at figuring out what other people are thinking at 4-and-a-half years of age.

In one study investigating preschoolers’ understanding of eye gaze, 4-year-olds were able to name which of two objects a child wanted based on a picture of the child’s eye gaze alone. Three-year-olds were not yet able to consistently predict the child’s desire based on what the child was looking at.

For this reason, it’s important to remember that while 3-year-olds have made leaps and bounds in their development of emotion language, their ability to apply that language to other people’s experiences is still growing.

In addition, the development of these abilities does not happen in one, single instance. From what scientists have found, children do not have a single aha moment in which the concept of theory of mind clicks.

Instead, scientists find that some time in their third year, children begin to reason using theory of mind in some instances, and that as they develop this ability, children begin to use it correctly more and more often.

Emotional Regulation

By 5 years of age, children have developed a set of self-regulation strategies and have learned to apply them in a variety of situations.

These strategies help adjust our emotional state to a comfortable level. For example, some common emotion-regulation strategies are breathing deeply to calm down after an injury or sitting down and counting to 10 when feeling overwhelmed.

Emotion-regulation develops along with brain areas active in executive functioning and with the help and guidance of caregivers and educators.

One effective way to help children regulate their own emotions is to follow three steps:

- Acceptance of emotion

- Recognition of emotion

- Resolution of emotion

The child must first accept that it’s okay to feel the emotion. Believing that an emotion is not acceptable can sometimes make an intensely emotional situation even worse.

Second, recognizing what emotion you are experiencing helps you figure out what the best strategy for resolution might be. If you’re feeling angry, smiling and thinking of something funny might not be as effective as when you’re feeling sad.

Another strategy that some children employ is called taking a self-distanced perspective. The idea behind this strategy is to create distance from yourself to help reduce the impact of the emotional response enough to think clearly about a resolution.

In one study on self-distanced perspective taking, scientists found that 5-year-olds, but not 3-year-olds, benefited from taking a self-distanced perspective on an executive-function task through third-person self-talk as well as taking the perspective of an exemplar other, for example, Batman, through role play.

This makes sense in the context of theory of mind development. To create distance from oneself, one must first have a sense of self and other internal mental worlds. As children’s understanding of theory of mind develops, they are better able to step outside of their own mental world as well.

F – Sense of Identity and Belonging

Self-Perception

The fourth Social and Emotional Development preschooler subdomain is Sense of Identity and Belonging. Part of children’s development in this subdomain is the development of their self-identity.

From 3 to 5, children begin to classify themselves and others based on visible attributes (like gender, race, and age), good and bad, and competency. They have begun to construct their own personal narrative and will often want to share their stories with you.

The development of self-identity can vary across cultures.

One way this can be studied is through children’s drawings of themselves and their families. Scientists compared the self and family portraits of children from a less individualistic culture, Cameroon, and a more individualistic culture, Germany.

Cameroonian preschool children drew themselves significantly smaller than German children of the same age in both their own self-portraits and in their family portraits. German children even drew themselves differently when alone versus in the family portrait. They drew themselves with a larger head in their self-portrait than in their family portrait, while Cameroonian children tended to draw themselves at the same size in both drawings.

Similar differences in self-portrait sizes have been found between other cultures as well.

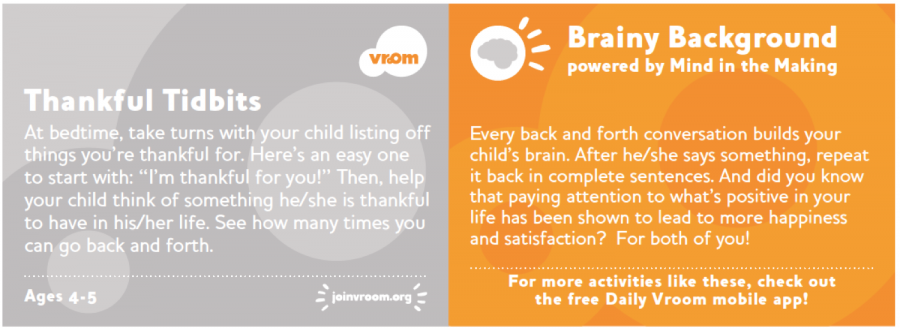

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to help build children’s social and emotional development.

What do you think of the idea? Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Thankful Tidbits

At bedtime, take turns with your child listing off things you’re thankful for. Here’s an easy one to start with: “I’m thankful for you!” Then, help your child think of something he/she is thankful to have in his/her life. See how many times you can go back and forth.

Ages 4-5

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

Every back and forth conversation builds your child’s brain. After he/she says something, repeat it back in complete sentences. And did you know that paying attention to what’s positive in your life has been shown to lead to more happiness and satisfaction? For both of you!

Group Structure

In constructing their own identity, children look at the group structure of the social world for information about themselves. Children develop not only a sense of themselves but also of how they fit into the social group structure.

Children are aware of group-based differences, such as race, and look to educators, parents, and books to learn about what those groups mean. In the preschool years, children begin to recognize their own race and racial group. Group identities can affect children’s sense of self-worth and self-confidence. Children will use information from those around them to figure out how they should be treated and how to treat others.

This often can be a difficult or uncomfortable area of development for caregivers and educators to navigate. But research on racism and racist thinking in young children shows that talking about race early and often actually decreases children’s racist thoughts.

One of the most famous studies on children’s thoughts about race was conducted in the 1940s and is called the doll test. In this study, children were asked about various positive and negative trait labels, such as smart, funny, mean, and dumb. When asked which doll the traits described, both black and white children were more likely to attribute positive traits with the white doll and negative traits with the black doll. These results now have been replicated time and time again, even in modern-day studies.

Children also will use race in social situations to make judgments about others. It is important to keep in mind that children are still trying to make sense of the world and are using the cues from those around them to do so.

Educators can help encourage children’s social identity development by using comments on personal differences to teach children. For example, if a child comments that another child’s skin is “dirty,” they can say, “Your skin is lighter and theirs is darker, but you’re both clean.”

Acknowledging differences and giving children a way to talk about them productively is one way to help combat racism and racist thinking.

Building Self-Confidence

One of the most important and lasting aspects of early identity development is that of self-confidence.

If day-to-day events seem to occur randomly, it can cause children a lot of anxiety. If life doesn’t make sense, it may feel too scary to fully explore. When children know what to expect, they are free to play, grow, and learn.

Part of constructing self-confidence is feeling that you have some control over your own environment. This is one reason why children may sometimes appear to have specific desires or needs. They are attempting to exert some control over their environment. Validating children’s desires and ability to control the environment within reasonable limits is a great way to help support their self-confidence.

If a child wants to put their toy on the left side of the table, rather than the right side, it may not seem important to you. But your confirmation that they can do this can mean a lot to the child. It means that their opinions matter, that you will respect them, and that they can exert some control over how their world is structured.

Imagine if you had someone making all the decisions for you, putting things in places that didn’t make sense to you or didn’t look right to you. You would probably get fed up and irritated with them pretty quickly.

Engaging children in the construction of their environment can help them feel that they have a sense of mastery and can help them construct their self-confidence. For example, letting children pick which table to put flowers on or where the crayons should go can help children not only feel more in control of their own environment but also demonstrates to them that you respect their opinions and models how to ask others for input in social interactions.

Reflection Point

Think about preschool children’s social and emotional development and how to encourage it. Pick one of the four subdomains in the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Social and Emotional domain for preschoolers:

- Relationships with Adults

- Relationships with Other Children

- Emotional Functioning

- Sense of Identity and Belonging

Now, recall a recent experience with a child that you think demonstrates learning in the subdomain you picked.

What would a future experience in which you could encourage a child’s learning in that subdomain look like?

References

References

Arterberry, M. E., Cain, K. M., & Chopko, S. A. (2007). Collaborative problem solving in five-year-old children: Evidence of social facilitation and social loafing. Educational Psychology, 27(5), 577-596.

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Brooks, R., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2015). Connecting the dots from infancy to childhood: A longitudinal study connecting gaze following, language, and explicit theory of mind. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 130, 67-78.

Brownell, C. A., Ramani, G. B., & Zerwas, S. (2006). Becoming a social partner with peers: Cooperation and social understanding in one- and two-year-olds. Child Development, 77, 803-821.

California Department of Education. (n.d.). Social-Emotional Development Domain: Foundations. [Online Resource]

Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning. (n.d.). What works brief: Fostering young children’s emotional literacy. [Online Resource]

Corriveau, K., & Harris, P. (2009). Choosing your informant: Weighing familiarity and recent accuracy. Developmental Science, 12(3), 426-437.

Dunfield, K., & Kuhlmeier, V. (2013). Classifying prosocial behavior: Children’s responses to instrumental need, emotional distress, and material desire. Child Development, 84(5), 1766-1776.

Hay, D., Payne, A., & Chadwick, A. (2004). Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(1), 84-108.

Paulus, M., & Moore, C. (2014). The development of recipient-dependent sharing behavior and sharing expectations in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 914-921.

Ramani, G. B., & Brownell, C. A. (2014). Preschoolers’ cooperative problem solving: Integrating play and problem solving. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 12(1), 92-108.

Rubeling, H., Keller, H., Yovsi, R. D., Lenk, M., Schwarzer, S., & Kuhne, N. (2011). Children’s drawings of the self as an expression of cultural conceptions of the self. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(3), 406-424.

Sesame Street. (2012, February 24). Sesame Street: Kids talk: Making friends. [Video]

Schmidt, Marco F. H., Rakoczy, H., & Tomasello, M. (2011). Young children attribute normativity to novel actions without pedagogy or normative language. Developmental Science, 14(3), 530-539.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Head Start Early Learning Outcome Framework: Ages birth to five. [PDF]

Vroom. (n.d). Vroom tips. [PDF]

White, R., & Carlson, S. (2016). What would Batman do? Self‐distancing improves executive function in young children. Developmental Science, 19(3), 419-426.

Zero To Three. (2016, February 2). From feelings to friendships: Nurturing healthy social-emotional development in the early years. [Video]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 7-1 Preschool social and emotional development. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]