5-3 Let’s Talk – Supporting Language and Literacy

A – Educator Language

Supporting Language Development

As educators, what can we do to support children’s language development?

Multiple studies have found that the more complex language educators use, the more complex language that children will learn to use as well. For example, one study explored whether children’s understanding of syntax—the way words are put together to form phrases, clauses, or sentences—was related to how complex their early childhood educators’ language was.

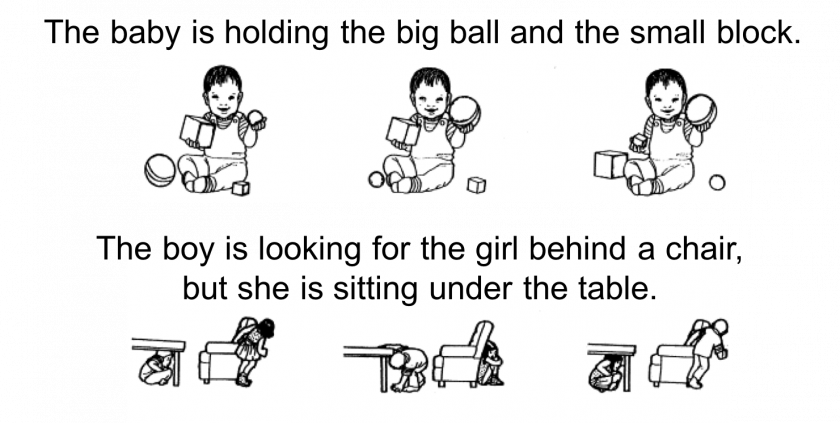

Children in the study looked at a series of three images and listened to an adult read a sentence. Then they were asked to pick which picture described the sentences.

Some sentences had varying numbers of noun phrases, such as “The baby is holding the big ball and the small block.” Others were multi-clause sentences, such as “The boy is looking for the girl behind the chair, but she is sitting under the table.”

To understand these two sentences, children have to understand the sentences’ syntax. They have to know that the order of the words is important to the meanings of the sentences. The researchers also looked at the educators’ syntax and measured how often the educators used complex sentences while they were teaching. They measured how often educators used sentences that had more than one clause. Again, one example of this is: “The boy is looking for the girl behind the chair, but she is sitting under the table.”

They also measured the average number of noun phrases that educators used in a sentence. For example, the sentence “The baby is holding the big ball and the small block” has two noun phrases.

Each child did this activity twice, once at the beginning of the year and once at the end.

Interactive: Impact of Educator Language

Interactive: Impact of Educator Language

This is an interactive! Use the slider in the interactive to explore the graph.

Learning Grammar

As you might have noted in the previous study, understanding grammatical rules is key as children begin to string words together into sentences.

Since many grammatical rules can be difficult to learn, children initially make some errors. For example, a child might say, “Dad go,” rather than “Dad is going.” Proper verb forms and the parts of words that go on the ends of verbs, nouns, and adjectives are often missing from early sentences. For instance, in the last example the child used “go” rather than “going.”

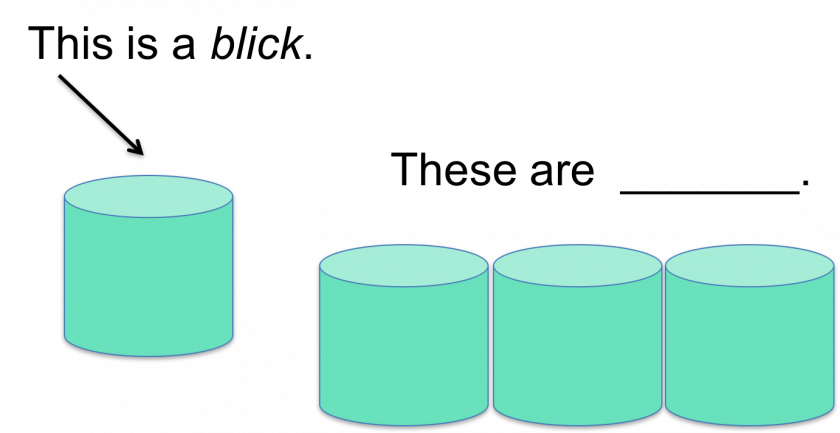

Studies show that children can learn the rules of grammar just from hearing these patterns. Scientists can use a simple game to test this. In the test, an adult shows a preschool-age child an unfamiliar object. This object has a made-up name, such as blick. The scientist then asks the child what the plural of blick is.

When asked, children say that the plural of blick is blicks, even though they have never heard this word before. They know that in English, we usually form plurals by adding s to the end of nouns. Children have heard other examples of plural words, which means they can generalize this knowledge to new words.

Because children are able to learn by hearing these patterns, the amount of speech that children hear, particularly complex sentences like we just discussed, is important. The more language children hear, the more their language abilities grow.

Note that while children are learning new grammatical rules, they will often make mistakes. These mistakes are signs that children are learning. They are practicing different rules that they have learned to see if other words follow those same rules.

As educators, we can support children’s language development by providing the correct form of verbs. If a child says, “I rided in the car,” we can say “Oh wow! You rode in the car! Who else rode in the car with you?” You don’t have to correct the child explicitly by saying, “It’s rode, not rided.” Children will learn the verb when adults use the correct form in their natural response. After children hear the correct use a few times, they will start to use the correct grammatical form in sentences.

Children learn grammatical patterns by listening and through conversations with others. Engaging children in conversations and modeling the correct form of the word extends children’s learning.

Elicitations and Extensions

We just talked about how conversations help support children as they learn grammar. Back-and-forth conversations are a powerful learning tool.

While children do learn a lot from listening, they also need to participate in back-and-forth conversations. It can be a challenge to engage with children in multi-turn conversations.

Two strategies to promote these back-and-forth conversations are elicitations and extensions:

- Elicitations are efforts, typically questions that the educator asks, that are meant to encourage children to talk. Open-ended questions, such as “How do you think the dog got outside?” are an example of elicitation.

- Extensions are efforts on the educator’s part to follow children’s lead by building on children’s topics of conversation and providing more information or explanation. Extensions can help to keep a child engaged in conversation and to deepen their thinking and learning.

Let’s look at these two examples. Both start with an elicitation—the educator asks a question to encourage a child to talk. The child, Shenay, responds “Making something.” At this point the two conversations diverge.

Elicitation

Educator: Shenay, what are you working on? (elicitation)

Shenay: Making something

Educator: Making something?

Shenay: Yes.

Extension

Educator: Shenay, what are you working on? (elicitation)

Shenay: Making something

Educator: You’re making something? Tell me about what you are making. (elicitation)

Shenay: A dog

Educator: You’re making a dog with floppy ears! (extension)

Shenay: Yeah, I love my dog.

In the first example, the educator repeats Shenay’s answer in the form of a question, and Shenay responds with “Yes.”

In the second example, the educator makes an elicitation effort: “Tell me about what you are making.” This time, Shenay provides more information—“A dog,” she says. This gives the educator an opportunity to extend the conversation. She adds, “You’re making a dog with floppy ears.” Shenay, still engaged, says, “Yeah, I love my dog.”

At this point, the educator might take the opportunity to extend again.

Research indicates that educators’ use of elicitations and extensions in back-and-forth conversations with children is positively associated with children’s vocabulary growth.

B – Predictor of Future Skills

Children’s language experience in preschool predicts their language and literacy skills in kindergarten and elementary school.

For example, in one study, researchers recorded educators in preschool programs during these times of the day: large group, book reading, small group, meals, and free play. The educators in the study wore small backpacks with a tape recorder that recorded what they were saying.

The researchers followed up with the children in the study and assessed their language and literacy skills in kindergarten and again in fourth grade. They found that early childhood educators’ use of strategies to extend conversations correlated positively with children’s narrative production, emergent literacy, and receptive vocabulary in kindergarten and their reading comprehension, receptive vocabulary, and word recognition in fourth grade.

In other words, when educators use strategies like extension or elicitation, they support children’s future language and literacy skill development.

The study also found that higher proportions of more sophisticated vocabulary words used by educators correlated with higher levels of emergent literacy and receptive vocabulary in kindergarten and receptive vocabulary, reading comprehension, and word recognition in fourth grade.

Finding Time to Talk

We’ve learned that children’s understanding of complex language correlates with how much complex language they are exposed to in preschool. And that back-and-forth conversations, where educators use elicitations and extensions, helps to promote vocabulary growth.

But with so much going on in the early learning environment, finding opportunities to engage in high-quality, back-and-forth conversations can be a challenge.

Mealtime and center time are key times in the day to work on children’s language development. Children are often in smaller groups during these times, and research indicates that children are more likely to engage in conversation when they are in smaller groups.

Children spend an estimated 30 percent of the day in free-choice center activities. Free-choice centers provide opportunities to have back-and-forth conversations that focus on topics that children are interested in.

But research indicates that, during center time, educators are the ones talking for about 80 percent of the time. Often the educator is the one who picks the topic of conversation, and many of the exchanges involve the educator commenting on the child’s actions.

This means that children don’t always have the chance to build their language skills through back-and-forth conversations.

There are several things that educators can do to support children’s language development and engage children in more meaningful, back-and-forth conversations.

During center time, educators can ask open-ended questions about children’s creations, or their play, and encourage children to propose explanations. Strategies like these help educators engage children in deeper thought.

C- Language Development Scenario

Applying what we know about language development

Read the scenario below and think about how you can support children’s language development through conversation.

Willow and Kai were playing with the miniature farm. They were moving around the plastic animals and making animal sounds.

“We want blankets,” Willow said, making the horse jump up and down.

“Nope,” said Kai. “You don’t need blankets. You are just a horse. You have fur!”

Letitia, the educator in their early learning program, overhead the conversation and said, “Willow, why do you think the horse needs a blanket?”

“Because he’s cold!” Willow said.

“Oh, you think it is cold in the barn?” the educator asked.

“Uh huh,” Willow said, pretending to shiver.

“Oh, I see,” Letitia said. “Kai, how does the farmer feel about the horse wanting a blanket?”

Kai paused. Then he said, “He is mad! He doesn’t think horses need blankets!”

Letitia said, “Are you remembering the story we read the other day? The farmer was mad. Remember, he was furious? Do you remember what that means?”

Both children shook their heads.

“That means he was really, really angry,” Letitia said. “Have either of you been furious before?”

Kai said, “I have!”

“When was that, Kai?” the educator asked.

“When my little brother knocked down my tower,” Kai said, scowling.

“That is a great example, Kai,” Letitia said. “That would make me furious too. So in the story, the farmer was furious at the horses for wanting blankets.”

Adapted from: Whorrall, J., & Cabell, S. Q. (2016). Supporting children’s oral language development in the preschool classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(4), 335–341.

Reflection Point

- What does this educator do to support children’s language development?

- What challenges do you have in finding time to have these types of conversations?

- What ideas do you have for including more of these kinds of conversations with children?

References

References

Bloom, P., & Kelemen, D. (1995). Syntactic cues in the acquisition of collective nouns. Cognition, 56(1), 1–30.

Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., DeCoster, J., & Forston, L. D. (2015). Teacher–child conversations in preschool classrooms: Contributions to children’s vocabulary development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30, 80–92.

Dickinson, D. K., & Porche, M. V. (2011). Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth-grade language and reading abilities. Child Development, 82(3), 870–886.

Huttenlocher, J., Vasilyeva, M., Cymerman, E., & Levine, S. (2002). Language input and child syntax. Cognitive Psychology, 45(3), 337–374. [Online Article]

Whorrall, J., & Cabell, S. Q. (2016). Supporting children’s oral language development in the preschool classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(4), 335–341.

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 5-3 Let’s talk – Supporting language and literacy. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]