4-4 Supporting Language Development

A – Best Way to Learn Language

Earlier, we talked about how, as children listen to the sounds of language, connections are rapidly forming between regions in their brain. But what type of experience with language is best? Infants hear language everywhere, from speakers on the radio to characters on television.

Remember that when infants are born, they are universal language learners. They are able to tell the difference between sounds in all of the languages spoken around the world.

But by age 1, children start to become native language specialists. They get much better at telling the difference between sounds in their own language and worse at telling the difference between sounds in foreign languages.

Researchers wanted to know how well English-learning 9-month-old infants could learn to tell the difference between sounds in a foreign language from different language sources. To do this, they compared how well English-learning 9-month-old infants learned foreign language sounds.

Infants came to the research lab for 12, 25-minute, language-learning sessions. Some of the infants spent all 12 sessions with a native Mandarin speaker. The Mandarin speaker read books, sang songs, and played with toys.

A second group of infants watched DVD recordings of the Mandarin speaker for 12 sessions.

A third group listened to audio recordings from the sessions.

All three groups were exposed to the same amount of language, but the types of experiences with the language were different.

Specialization in Languages

Specialization in Languages

Use the slider interactive below to explore this graph.

B – Interactions Drive Language Growth

Research shows again and again that early interactions, especially those that include back-and-forth exchanges, are key to early language learning. These interactions allow adults to customize their responses to children’s needs. This way, adults can follow a child’s interests through conversation or play. These are also called serve-and-return interactions.

Children gain extra confidence to take part in communication when adults listen and respond. By doing this, you are reinforcing children’s efforts to learn language.

These kinds of interactions can even begin long before the child is speaking. Let’s look at several things that parents and educators can do to help language development during back-and-forth interactions.

Parentese

Parents and educators can talk to their child in parentese, or infant-directed speech. Listening to parentese can actually help infants learn. And they love to listen to it.

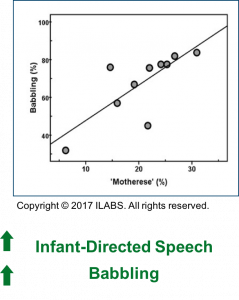

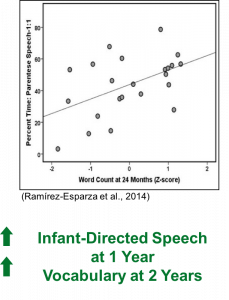

As the graph on the left shows, infants who heard more motherese, a similar concept to parentese, babbled more in infancy. Because babbling is essentially practice for later communication, this is an important step in language learning.

Not only does parentese give children an opportunity to practice speaking, but it also helps children learn new words. As shown in the graph on the right, infants who hear more parentese at age 1 had a higher vocabulary word count at age 2.

How Infants Learn from Parentese

Back-and-forth exchanges with infants are a perfect time to use parentese. To use parentese, you use a sing-song, exaggerated tone of voice. It sounds something like: “Ahhh, how do those niiice, cleeeean, clooothes feeeel?”

Parentese is helpful in language growth because the syllables and vowel sounds are accentuated. This makes them easier for babies to recognize.

When you are first learning a language, it can be very difficult to hear when new words start and stop—they all blur together. But if someone speaks the language slowly and carefully, it is easier to tell when one word stops and the next begins.

Unlike simply speaking slowly and clearly, parentese not only exaggerates different words, but it also accentuates vowel sounds, which helps infants learn those sounds.

Any time is a good time to use parentese. Think about times in the day when you might have routine, one-on-one interactions with children. Perhaps during moments in the day, such as diapering or handwashing.

C – More Ways to Grow Language

Imitation

Another way to support early language development is to model language and communication for children. Infants learn from watching.

One of the most important ways that infants learn is imitation. Starting immediately after birth, infants can observe and imitate, or copy, facial expressions and gestures.

Later, infants use imitation to learn about objects, themselves, and other people. They learn the similarities and differences between themselves and others, just by watching. Children even use imitation to learn language. They do this by listening to and mimicking language sounds and lip movements.

Infants are most likely to learn through imitating a responsive adult, especially a caregiver who is able to use body language cues to understand children’s feelings and needs.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to use imitation during everyday interactions with children.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Sound Makers

When you’re in the park, take turns with your child making different sounds with your voices, hands, and feet. Stomp really loud or clap your hands up high. When your child makes a sound, imitate it and then make a new one. How many different sounds can you two make?

Ages 1-2

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

The “Sound Game” gives your child practice focusing and controlling his/her behavior. To copy your sound, your child has to pay attention and remember it. Waiting for his/her turn takes self control. Your child will need these thinking skills in school, work and life.

Read the Vroom tip. Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit? Gazes and Gestures

Gazes and Gestures

In addition to imitating our actions, infants are also looking for any clues we can give them about what we are trying to communicate. Two big clues are where we are looking and what we are pointing at.

Toward the end of their first year of life, infants begin to follow our gaze toward what we are looking at. They also begin to look where we are pointing and to use the pointing gesture themselves to communicate their own interests and desires. Following our gaze and looking where we are pointing helps infants to isolate and identify what it is that we are talking about.

And before they have the words for objects, pointing helps infants direct our attention to things that they want, are interested in, or need. Infants around the world use pointing as one of their early communication tools.

Looking and Pointing

In fact, research indicates that looking and pointing in infancy is linked to higher vocabularies in toddlerhood.

Infants were initially tested on gaze following and pointing at 10 to 11 months of age. Then researchers measured their spoken vocabulary size, or expressive vocabulary, at 10, 14, 18, 20, and 24 months.

Interactive: Looking and Pointing Boosts Language

Interactive: Looking and Pointing Boosts Language

Use the slider below to explore the graph.

Sharing Attention

Why are gaze-following and pointing related to vocabulary?

When you show an infant an object, either by holding it or pointing to one further away, you are giving them a cue to pay attention. Infants use this cue to quickly figure out the names of the objects that you are talking about.

We can help infants develop their vocabulary by using these communication tools to engage them in joint attention. We can look at infants, catch their attention, and then deliberately look at an object we want to talk with them about. We can look between the object and the infant, shifting our gaze as we continue to engage. We can also point at objects, long before infants begin to point themselves.

Modeling these communication tools will not only help children focus on what we are talking about, but it will also help them learn to use these tools themselves as they continue to build their communication skills and vocabularies.

Remember that children who follow our gaze and where we point and then point themselves tend to have larger vocabularies.

The child on the left may focus on the educator and follow the educator’s attention to see what they are doing. Here, the educator is planting a flower. They’re now both focused on the same plant, as well as each other—this is joint attention.

Early childhood educators can use this opportunity to label objects and describe experiences to infants. This helps infants learn the meaning of those labeled objects and experiences.

During joint attention, infants connect words to objects and begin to build their vocabulary. Infants learn nouns—the names of objects and people—first. Sharing joint attention is the perfect time to help young infants begin to learn the names of things in their world.

D – Supporting Early Literacy

You might think that from birth to 3 years, children are too young to be developing literacy. But just like language learning begins with infants listening to sounds well before they learn words or language, literacy also begins much earlier, well before children are able to distinguish written words.

Connecting Language and Literacy

We will not discuss early literacy in great detail in this lesson, however here are a few ways that we can support the very early stages of literacy development:

- Repeat songs and stories so children can practice their own narrative and language skills by repeating the same songs and stories on their own.

- Provide children with books to touch, look at, and interact with to give them familiarity with books and written text. Modeling how to turn pages and pointing to the words and pictures in a book as you read will help children learn about reading skills, direction of text, and symbolic representation, or how words or pictures on a page can have meaning.

Just as children learn language best in back-and-forth interactions, so they learn literacy. Ask children questions about stories as you are reading to them. See if they can remember parts of the story on their own or maybe even come up with new adventures for familiar characters.

Finally, encourage children’s fine motor skill development through practice with drawing, stencils, outlining, coloring, and other forms of drawing that require more and more control of the writing tool. This will help children develop control over their own marks and drawings.

Like language, the development of literacy skills also begins in early childhood. You can help support this development by reading and engaging children, even infants, during the reading process.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip to get more ideas about how to support early literacy skills during everyday interactions with children.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Shopping List Scribble

Writing a shopping list? Talk to your child about what you need. Read what you are writing down: “Milk, eggs, cereal.” Invite your child to “write” or draw on the list too and to tell you what he/she is thinking about when he/she makes those marks on the paper.

Ages 2-3

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

Your child is learning that the marks that you and he/she make on paper have meaning. Understanding that one thing stands for another is an important thinking skill in learning to write, read and communicate.

Read the Vroom tip. Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit?

Video: Early Essentials Webisode 9: Language Development (24:35)

This video has three examples of educators supporting language development:

- At an early learning program during diapering

- At an early learning environment during outside playtime

- During a home visit

As you watch the video, think about how the educators support language development.

Video Debrief

What did the educators talk about? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

We noticed that educators talked about:

- Responding to early attempts at language

- Matching infants’ sounds

- Introducing young children to the environment around them, including words and books

- Talking, singing, playing, and reading books with children

- Labeling objects in the environment

- Narrating what children are doing and what adults are doing

- Finding out from families about children’s home languages and family language goals for their child

- Including children’s home languages in the early learning environment

The other main take-away here is that back-and-forth interactions that help build language can happen at any time. They can happen during routines, such as mealtime, handwashing or putting on jackets or boots. They can happen on the bus or during walks. The quality of interactions, rather than the quantity of interactions, is important.

Everyone has the tools needed to help a child develop language, no matter how busy life gets. These early, quality interactions and language exposure are essential to children’s successful language learning.

Reflection Point

Language learning can happen anywhere and at any time. During your daily face-to-face interactions with children, think about including some of the language-learning ingredients that we just discussed.

- Can you add parentese to diapering or feeding?

- Could using imitation help a child learn words to describe emotions?

- If you want to talk to a child about an object, how could you use pointing and eye gaze to help the child discover what you are talking about?

- During times when you and a child are both looking at or playing with the same object, how could you boost language growth by making an effort to describe the object or an interaction that you are having?

Including some of these ingredients into your daily work with children can help turn everyday routines into language growth opportunities.

References

References

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Brooks, R., & Meltzoff, A. (2008). Infant gaze following and pointing predict accelerated vocabulary growth through two years of age: A longitudinal, growth curve modeling study. Journal of Child Language, 35(1), 207–220.

Kuhl, P., Tsao, F., & Liu, H. (2003). Foreign-language experience in infancy: Effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(15), 9096–9101.

Kuhl, P. K. (2010). Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron, 67(5), 713–727.

Kuhl, P. (2007). Is speech learning ‘gated’ by the social brain? Developmental Science, 10(1), 110–120.

Garcia-Sierra, A., Rivera-Gaxiola, M., Percaccio, C. R., Conboy, B. T., Romo, H., Klarman, L., … Kuhl, P. K. (2011). Bilingual language learning: An ERP study relating early brain responses to speech, language input, and later word production. Journal of Phonetics, 39(4), 546–557. [PDF]

Ramírez‐Esparza, N., García‐Sierra, A., & Kuhl, P. (2014). Look who’s talking: Speech style and social context in language input to infants are linked to concurrent and future speech development. Developmental Science, 17(6), 880–891. [Online Article]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, Early Head Start National Resource Center. (n.d.). Early essentials webisode 9: Language development. [Video]

Vroom. (2017). Tools and resources. [Website]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 4-4 Supporting language development. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]