4-3 Dual Language Learning and Development

A – Learning More than One Language

At this point, we’ve primarily focused on how to learn a single language, but what happens when a child is exposed to and trying to learn more than one language?

Maybe at home the child speaks Spanish, while at school they speak English. Or maybe their extended family speaks only Mandarin, but their immediate family lives in the United States. How does learning more than one language, or dual language learning (DLL), affect language development?

What is Bilingualism?

Bilingualism is the ability to speak two or more languages. Bilingual and dual language learner (DLL) are both terms you may hear referencing children who speak more than one language.

In contrast, someone who speaks one language is called monolingual.

Children who are dual language learners are learning two or more languages at the same time, or learning a second language while continuing to develop their first or home language.

About 20 percent of people in the United States speak more than one language at home. Bilingualism is even more common around the world. Roughly two-thirds of the world’s population knows more than one language.

People who are bilingual are diverse, learning languages at different ages and in different contexts.

Two Types

Proficiency and dominance in languages varies among children who are dual language learners.

Dual language learning can occur in a variety of ways.

Some children start learning two languages from birth. They are simultaneous bilinguals. Simultaneous bilingual speakers have two native languages.

Other children learn one language before they learn another one. They are sequential bilinguals.

B – Developing at Same Rate

Sometimes caregivers and educators are worried that children who are learning two languages will have language delays.

But research does not support this. Children who are learning two languages reach developmental milestones at the same pace as children learning only one language.

When thinking about language milestones, it is important to consider how many words children know in each of the languages they are learning. Research indicates that language growth in bilingual and monolingual children is very similar.

Dual Language Development

Regardless of how many languages they are learning, children usually say their first words around 1 year of age. A bilingual’s first words may be in one or both languages. It depends on children’s experiences with each language.

Bilingual vocabulary and grammar development show the same pattern as monolingual language development. Monolingual and bilingual children begin to combine words around 18 months. By 3 to 4 years of age, children produce more complex sentences.

Just like monolinguals, bilingual children show variability in the ages at which they reach each milestone. Simultaneous bilingual children may reach these milestones at the same time in both languages, while sequential bilingual children may reach milestones at staggered times—months or even years apart.

It is also important to consider that bilingual children have different language experiences at home. Depending on whether you work with simultaneous or sequential bilingual children, and the amount of each language they hear at home, you can expect to observe different language behaviors. For example, you might notice that the bilingual children you work with are more comfortable speaking one language than the other or that they switch between languages.

Regardless of these children’s individual language experiences and developmental trajectories, you can support dual language learning in any early learning environment.

Quality Interactions from the Start

Whether children are learning one or more languages, it is important that they have high-quality language interactions with the adults in their lives. These interactions build a strong foundation for language learning. Knowing how to learn a language is a skill that helps children learn a second language.

Even if a child does not speak English well when they start in your program, this does not necessarily mean that they have a language delay. When a child has a strong foundation in their home or native language, they will likely be able to quickly learn a second language.

To build a strong foundation in their home language, educators can encourage parents to speak the language that they are most comfortable with and feel competent using. These interactions not only help children develop their first language, but they teach children what they need to do to learn any language.

Interactive: Language Developing Rates

Interactive: Language Developing Rates

Use the slider interactive below to explore this graph.

Reflection Point

As we think about the intersection of language and culture, let’s consider the importance of language to you and your community. Consider these questions:

- Why is bilingualism important?

- How do language and culture connect?

- What does your language—or languages—mean to you?

- Why is it so important for you and your community to maintain your home language?

C – Cognitive Benefits of Bilingualism

As we just discussed, for children who are dual language learners, learning both languages is incredibly important to their culture and identity.

In addition to these benefits, there is more and more research indicating that knowing and learning more than one language has cognitive benefits as well, including mental flexibility and cognitive control. Both of these have to do with something we call cognitive flexibility. This is the ability of our brain to do things like quickly switch from one task to another, come up with creative solutions to problems, or multitask.

Children who are learning more than one language tend to be particularly good at doing these types of activities because they have a lot of practice switching between languages.

Sensitive Period for Language

Children who are learning two or more languages also get a boost in the length of time that their brain is particularly sensitive to learning language.

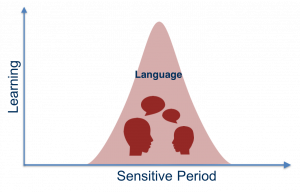

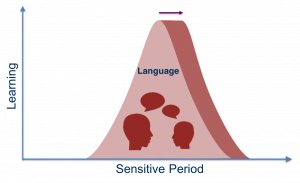

You might remember the sensitive period for early language learning that we discussed earlier. The sensitive period is the time in development when children’s brains are especially ready to learn language.

You can see the sensitive period represented by this graph. The time under the peak of the curve is the core of the sensitive period. The ramp-up and the ramp-down represent the time leading into and the time leading out of the sensitive period.

Although monolingual and bilingual language development are similar in many ways, the time period in which sensitive periods occur for monolinguals and bilinguals is one of the few areas where we see some differences.

Bilingual Sensitive Period

It turns out that children who are learning two languages have a longer sensitive period for language learning than children who are learning just one.

It’s important to note that this extended sensitive period is NOT a delay. It’s actually an extension of time during which those children can learn a language more easily.

If you think about how the infant brain is using patterns to determine which sounds are important for a child’s home language or languages, this extended sensitive period makes sense. This extra time allows children to accumulate all of the patterns they need to understand the languages they are learning.

Other than this extended sensitive period, children who are learning more than one language learn those languages in the same way that monolingual children learn a single language.

Interactive: Brain Specialization

Interactive: Brain Specialization

Use the slider interactive below to explore this graph.

D – Cognitive Flexibility

Code-Switching

You may notice that children who are dual language learners switch back and forth between their languages or mix languages within a sentence or phrase.

For example, a child who is a dual language learner of Spanish and English might say, “More leche” (more milk), or “I like to cantar y bailar every day” (I like to sing and dance every day).

This is an example of the mental flexibility of children who are learning more than one language. This skill is called code-switching.

Code-switching is evidence that children are learning to decode multiple languages. It is a strategy that children use to negotiate or construct meaning within and across languages.

Activity in Prefrontal Cortex

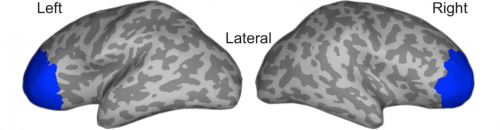

Children who are dual language learners show increased activation in an area of the brain called the pre-frontal cortex.

The pre-frontal cortex is the area of the brain responsible for many important cognitive functions, like planning, paying attention, solving problems, and switching between tasks.

This is an MEG brain map showing the right and left hemispheres of the brain. The portion highlighted in blue is the area of infants’ brains that researchers measured as children heard the language stimuli. This is the pre-frontal cortex of the brain.

Activity in the pre-frontal cortex is associated with many important cognitive functions, such as the skills involved in mental flexibility and cognitive control, both of which have to do with cognitive flexibility. Again, this is the ability of our brains to quickly switch from one task to another, as well as multitask.

A growing number of studies suggest that being bilingual comes with increased cognitive flexibility.

Interactive: Cognitive Flexibility – Name the Color

Interactive: Cognitive Flexibility – Name the Color

To give you an idea of what cognitive flexibility feels like, play a name-the-color game. In the interactive below, you will see a series of words in different colors, like BLUE. As fast as you can, type the first letter of the color that corresponds with the actual color of the word, NOT the color the word represents. Try it out and good luck!

Activity Debrief

Activity Debrief

How well did you do? What did you notice?

This test is called the Stroop Test, and it’s a common way that researchers measure cognitive flexibility in adults.

You might have noticed that at first, the written name of the color matched the color of text. At some point, though, the written name of the color was different than the color of the text. This probably made it much harder to say the name of the color of the word quickly.

Tests like the Stroop task demonstrate the brain’s ability to switch between tasks. To be fast at the task, you have to ignore the word and focus on the color. This is hard to do since we are all so used to reading automatically.

Why it matters

Your brain has to inhibit its natural tendency to read, but focus on colors instead. Because people who are learning more than one language have natural practice at switching between languages, they tend to complete Stroop tasks more quickly and accurately than people who are monolinguals, showing their mental flexibility. However, practicing Stroop tasks and other mental flexibility games can allow anyone to improve their cognitive flexibility.

E – Supporting Dual Language Learners

There are several things you can do to support children who are learning more than one language:

- Talk with bilingual families to learn which languages children hear and speak at home.

- Create a welcoming environment for children who are dual language learners, include their home language when possible, and individualize support for them as you can.

- Use visuals to help children understand.

You should also assess development and learning of children learning more than one language by using all of their languages.

Finally, if you or your colleagues can provide bilingual experiences to children, you might read aloud to children in each of their languages. For example, you can read one book in English and another in Spanish. Reading aloud gives children more opportunities to become familiar with the sounds of language.

Educators who do not speak a child’s home language can include culturally and linguistically appropriate materials when available.

Dual Language Learner Resources

If you are interested in more information about children who are learning more than one language or want more information on how to support children who are dual language learners, here are some resources to explore on the Office of Head Start’s Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center website:

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, National Center on Cultural and Linguistic Responsiveness. (n.d.). Gathering and using language information that families share. [PDF]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Culture & Language: Planned language approach. [PDF]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Culture & Language: Dual language learners toolkit. [Website]

Video: I Love Me (1:14)

Let’s watch a video called I Love Me that features an early childhood educator working with a group of children, some of whom are dual language learners.

While you watch the next video, consider these questions:

- What does the educator do to help support the children’s language development?

- What strategies does the educator use that could apply to a child who speaks a different language?

Video Debrief

What did you notice about the educator? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Here are some things we noticed:

- The educator uses language with the motions.

- She models the motions.

- She gestures to help the children identify their body parts.

Although the educator uses both English and Spanish, educators should use code switching in intentional ways instead of doing simultaneous interpretation, or alternating languages as they teach. One example might be when an educator reads one line of a book in one language then repeats it in another.

Section Summary

In this section we talked about how the brain is prepared to learn two languages at the same time.

- Bilingual language development is similar to monolingual language development. Children who are learning two languages reach developmental milestones at the same rate as children learning one language.

- Bilingualism is also associated with cognitive advantages, like greater cognitive flexibility.

- Whether children are learning one or more languages in the first years of life, we know it is important for them to have high-quality language interactions with the adults in their lives from the start. These interactions build children’s brains and help to create a strong foundation for language learning.

References

References

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2022). Cognitive flexibility demo. University of Washington. [Video File]

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). I love me. University of Washington. [Video File]

Ferjan Ramírez, N., Ramírez, R., Clarke, M., Taulu, S., & Kuhl, P. (2017). Speech discrimination in 11‐month‐old bilingual and monolingual infants: A magnetoencephalography study. Developmental Science, 20(1), 1–16

Hoff, E., Core, C., Place, S., Rumiche, R., Señor, M., & Parra, M. (2012). Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language, 39(1), 1–27.

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643–662. [Online Article]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, National Center on Cultural and Linguistic Responsiveness. (n.d.). Code switching: Why it matters and how to respond. [PDF]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Early Childhood Development. (2017, June 19). Dual language learners: Supporting the development of dual language learners in early childhood programs. [Website]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 4-3 Dual language learning and development. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]

Developmental progressions are the skills, behaviors, and knowledge that children demonstrate as they move toward goals in different age ranges.