4-1 Language and the Brain

A – Communication

Communication is the act of sharing one’s thoughts or information in some visible or audible form. It can take the form of verbal speech, physical gestures, or both together.

Take a moment to think of some of the different ways you communicate with both children and other adults. What do you do if they can’t hear you? Or if they can’t see you?

Types of Communication

- Non-verbal communication comes in many forms like pointing gestures or facial expressions.

- These non-verbal forms of expression are some of the earliest forms of communication that children engage in.

- However, you may be surprised to realize that even young infants engage in what is considered verbal expressions of communication, such as making cooing sounds when happy, and crying when distressed.

- Language itself is a specific form of expression that is marked by the use of words to communicate ideas in a structured way.

Basics of Language

Language is knowledge pulled from the external world. Children learn it from exposure to other people, society, and sets of rules.

There are three basic characteristics common to all language.

- Language is acquired, meaning that it is a learned skill. Children learn language from the people around them and their interactions with those people. Language is acquired from the outside in, meaning that children speak out loud before they can internalize language (i.e., think to themselves). Children who are not exposed to language—note that this is very rare—have a difficult time learning it later in life or are not able to learn it.

- Language is socially constructed. The society and culture in which a child lives will determine the meanings of words and when and where to use different words.

- Language is governed by a set of rules. The rules between different languages may differ but within a single language those rules will be more or less consistent. For example, in English you add ed to the end of a verb to mark that something happened in the past.

So, how do infants go about acquiring language? We will first cover how the brain processes speech sounds and how scientists study language learning in the infant brain.

Learning in the Womb

When infants are born, their brains are primed to learn language. From the start, infants begin learning the language or languages that surround them.

All around the world, typically developing children learn their native language effortlessly. Most children will learn to speak at least one language by the age of 3 or 4. But how are infants so good at learning language?

Scientists have been trying to understand how children learn language for decades. New science tells us that an infant’s language learning begins very, very early. In fact, research shows that experience plays an important role even before children are born. Beginning in the third trimester of pregnancy, developing infants are able to hear the sound of their mother’s voice from inside the womb.

This means that the baby can hear whatever language or languages the mother is speaking. Since the mother’s body amplifies the sound for the baby, only the mother’s voice is loud enough to be heard from inside the womb.

Recognizing Mother’s Language

Are infants learning anything as they listen to the sound of their mother’s voice? To find out, researchers played vowel sounds for newborn infants through special speakers. The vowel sounds were from their mother’s home or native language and from a foreign, non-native language.

Researchers measured how many times the newborn infants sucked on a pacifier while they listened to the sounds. When the infant was more interested in a sound, they would suck on the pacifier faster than when the infant was less interested. Infants are naturally more interested in things they don’t recognize.

The researchers found that infants sucked on the pacifier more when they heard the foreign language sounds. This indicates that infants didn’t recognize the foreign language sounds but they did recognize the sounds of their mother’s home language.

While infants are in the womb, they listen to their mother’s voice and learn from it.

B – Experience Shapes Language

We just learned that infants are able to tell the difference between the sounds of their home language and foreign languages at birth.

For the first few months of life, infants can tell the difference between all of the sounds of all of the languages spoken worldwide. They are citizens of the world. But very quickly, children’s experiences begin to shape what connections form in their brains as they learn language. By 10 to12 months of age, they are already becoming native language specialists.

In other words, they are getting better at telling the difference between sounds in their own language. At the same time, their ability to tell the difference between sounds that aren’t used in their native language or languages is getting worse.

Interactive: Distinguishing Sounds

Interactive: Distinguishing Sounds

Use the slider interactive below to explore this graph.

Reflection Point

Consider the question: What can we do to help very young children develop language skills? Make sure to consider activities for children who are learning a different language at home.

We will also discuss specific supports to use with children who are dual language learners later in the course, but this question can help us begin to focus on this topic.

Some additional questions might be:

- What kinds of practice might children who are dual language learners need in particular?

- What kinds of connections do we want to promote with language learning activities?

- How can you build language learning into activities you already do every day?

C – Language Brain Areas

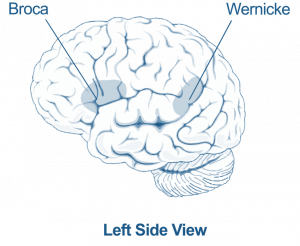

Wernicke’s area: Language perception and Broca’s area: Language production

What is happening in the infant brain as they learn language?

While there are many regions of the brain that are important for language, we will focus on two regions of the brain that are important for speaking and how these regions begin to work together.

- Wernicke’s area is important for language perception, or how we recognize particular sounds as language.

- Broca’s area is important for language production, or how we produce speech sounds.

In the adult brain these regions closely coordinate with each other. As we listen to language and engage in conversations, these areas in our brains are actively working together and sharing information.

These regions also coordinate with hearing or auditory regions of the brain and motor parts of the brain, which are important for directing the muscles we use to speak.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) Machine

Scientists wanted to know if Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas were active when children learn language. To find out, they used a brain imaging tool called magnetoencephalography, or MEG for short.

MEG is harmless, noninvasive, and silent and provides scientists with a millisecond-by-millisecond reading of what parts of the brain are active during a specific time period.

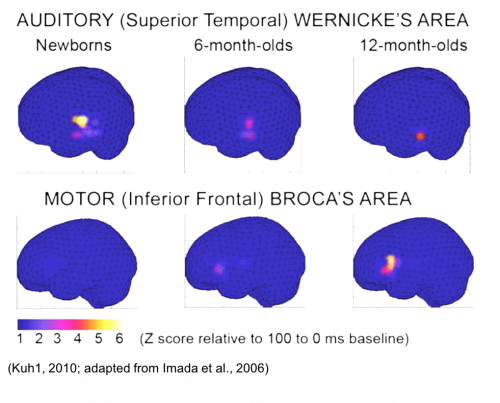

In one MEG study, newborns, 6-month-olds, and 12-month-olds listened to speech sounds while they sat in the MEG machine. The MEG measured infants’ brain activity in Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas while they listened to those speech sounds.

Activation of Language Brain Areas

The activity from all of the infants’ brains in the study was averaged together and the averaged brain activity is pictured here on these blue model brains as pink and yellow regions.

First look at the top row of brains. You’ll notice that all three brain models have brightly colored areas. This means researchers found that, while listening to language sounds, the region of the brain that is important for speech perception—Wernicke’s area—was active in newborns, 6-month-olds, and 12-month olds.

Now look at the row of brains on the bottom. You’ll notice that the leftmost brain model does not have any brightly colored areas, while the middle one has a lightly colored area and the one on the right has a very brightly colored area.

This set of results shows that in newborns (the leftmost brain models), the region important for speech production—Broca’s area—isn’t showing any activity. This makes sense. In newborns, the language perception and language production regions aren’t yet coordinated.

Only six months later (the middle brain models), the language perception and production regions of the infant brain are active at the same time. This is just around the time that infants are learning to babble.

But the infants aren’t actually babbling while they are in the MEG. They are just listening silently to language sounds. It is as if the infant brain is practicing while listening, trying to figure out how to produce all the sounds it hears every day. This pattern of brain activity suggests that the speaking and listening parts of the infant brain are beginning to work together. Over the past six months, connections between these two brain regions have grown. The connections have strengthened as the infants listened to language.

At 12 months (rightmost brain models), many infants are beginning to say their first words. By this age, simultaneous activity in both the production and perception areas of the brain is even stronger.

This coordinated brain activity is the result of both biology and experience. Early experiences with language are especially critical for infants. The infant brain is beginning to connect and coordinate these regions long before they utter their first word.

Sensitive Period

Children are incredibly good at learning language.

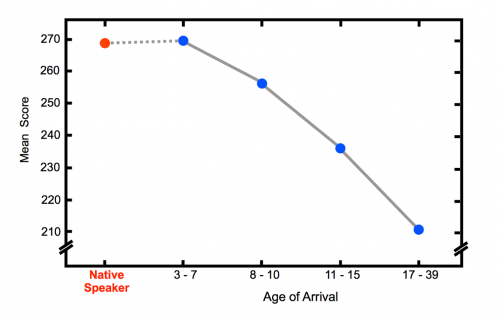

Remember this graph from Lesson 2? It describes the research findings of scientists who found that the older a person was when they started learning English, the worse they scored on the grammar test.

Again, this doesn’t mean that we can’t learn a second language as adults. We can always learn new things. It just means that it will be harder for us.

This is partly due to how our brains develop. When a child is young, connections form at a rapid rate, and the brain is particularly sensitive to new experiences.

But as we age, we stop making as many new connections between neurons. Our brains are less sensitive to the experiences we have in our everyday lives. While we can still learn new things as adults, we will likely have to try harder, or repeat the task more times than we would if we were learning the same thing as a child.

D – Practitioner Application

So what does this research mean for people who work with infants and toddlers every day?

- Children build their brains over the course of childhood.

- Connections form in their brains, and what they learn is a result of both their biology and their experiences.

- Children’s brains are primed to learn language, and they often appear to be natural language learners.

- Even if children are not yet talking, they are listening to what others are saying and forming connections in the language regions of their brains.

We can help children by making sure that they have plenty of rich language experiences to support their learning. This is true whether a child is learning one language or more than one.

Talking a lot—for example, narrating what you are doing as you are changing a diaper or helping a child into their pajamas—is one of the best ways to support language growth. Singing songs and reading books are also excellent ways to provide children with rich language experiences. Even if a child is too young to understand the story, you can still point to pictures in a book, name them, and describe them. And being close to you during story time and listening to your voice will help them associate reading with being comfortable, safe, and enjoyable—setting the stage for later literacy.

We will circle back to other things that adults can do to help support language growth later in this lesson.

References

References

Berk, L. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Imada, T., Zhang, Y., Cheour, M., Taulu, S., Ahonen, A., & Kuhl, P. (2006). Infant speech perception activates Broca’s area: A developmental magnetoencephalography study. NeuroReport, 17(10), 957–962.

Johnson, J. S., & Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21(1), 60–99.

Kuhl, P. K. (2010). Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron, 67(5), 713–727. [Journal Article]

Kuhl, P., Stevens, E., Hayashi, A., Deguchi, T., Kiritani, S., & Iverson, P. (2006). Infants show a facilitation effect for native language phonetic perception between 6 and 12 months. Developmental Science, 9(2), F13–F21.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders. (2015, December). Voice, speech, and language aphasia. NIDCD Fact Sheet. Bethesda, MD: NIDCD Information Clearinghouse. [PDF]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 4-1 Language and the brain. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]