13-1 Toxic Stress

A – Types of Stress

Stress Is a Continuum

We will talk about toxic stress in a moment, but before we do, take a moment to think about what the difference is between normal, everyday stress and toxic stress.

Not all stress in a child’s life is toxic. In fact, some stress is good stress. Positive stress is an important part of healthy development. Positive stress is the result of common experiences in a child’s life like starting school or going to the doctor’s office to get a shot.

These stressful experiences don’t last very long and are eased by the presence of a supportive adult. These early life experiences with positive stress help children learn how to cope with stressors that they will face throughout their life.

Tolerable stress is a longer stress response to a more intense situation like the loss of a loved one or experiencing a natural disaster like a tornado. If the child has the help of a supportive adult to buffer the stress, then these situations don’t necessarily lead to lifelong, lasting effects.

Toxic stress is the result of prolonged experiences of adversity, such as emotional or physical abuse, neglect, exposure to violence, a caregiver who has a mental illness or abuses substances, or the combined effects of poverty in the absence of buffering by an adult.

Toxic stress can have a negative, lifelong impact.

Next, we will watch a short video to help us think more about these terms.

Video: Toxic Stress (4:07)

This Alberta Family Wellness Toxic Stress video describes what toxic stress is and how it is different from positive and tolerable stress. It is an overview of the differences between the three different types of stress: positive, tolerable, and toxic.

Watch Toxic Stress from Alberta Family Wellness on YouTube.

Video Debrief

How would you buffer a child’s stress? What could you do to support a child who is experiencing a stressful situation? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answer

In this video, we learned more about the different types of stressors a child faces in their early years. Research indicates that the presence of a supportive and responsive adult during a stressful situation can help buffer and mediate the stress response. Supportive adults can buffer children’s stressful experiences, like a natural disaster, and prevent those experiences from eliciting a toxic stress response. We found the following to be possible responses to the questions:

- Create and provide an environment where children feel safe. This may look different for each child but reminding children that they are safe and telling them that what you are doing to keep their bodies safe can help.

- Be available and responsive, paying attention to children’s behavior, listening to what they say, and responding warmly and sensitively to their needs.

- Maintain routines as much as possible. When children are going through a stressful situation, having some anchor like a routine can help them cope.

- Model coping skills like taking deep breaths or a few minutes to calm down after experiencing big emotions and listening to others’ points of view.

- Let children practice coping with some stresses like disappointments. If children never have the opportunity to practice their coping and self-soothing skills, then it will be more difficult for them to deal with larger stresses later in life. Letting children experience stress doesn’t mean that you aren’t there to help them. Help children cope by talking about ways to process their disappointment or sharing what you do to help yourself feel better when you are disappointed.

- Exercise! Physical movement is helpful to children and adults who are experiencing stressful situations. Provide lots of opportunities for children to move their bodies during play.

What is Toxic Stress?

As you begin to get a sense of what toxic stress is, try to think of examples of everyday stresses that are toxic and ones that are not toxic. Not all stressors are toxic. Also consider: What makes toxic stress so toxic?

Video: How does the Toxic Stress of Poverty Hurt the Developing Brain? (10:03)

The video How Does the Toxic Stress of Poverty Hurt the Developing Brain? illustrates how toxic stress affects children’s development using a case study of a mom and four children from Honduras living in the U.S. and the father living abroad. Both the mother and the children experienced toxic stress that adversely affected them. A commercial will play before the video begins.

Read the Full Transcript at PBS.org.

This video defined the term toxic stress, and we learned about a family that experienced toxic stress.

Video Debrief

What makes toxic stress so toxic? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answers

Examples are:

- Toxic stress can disrupt brain circuits and create a weaker foundation for circuitry that is essential for learning, memory, concentration, solving problems, and self-regulation.

- Stress becomes toxic when it is unrelenting and children have little or no support from adults in their lives to help them manage stressful situations and build resilience.

B – Impact of Stress on the Body and the Brain

Extended periods of stress can have a lasting impact on the brain and body. Let’s take a closer look at the body’s stress response and the result of long-term exposure to this stress.

When we come across a possible threat in our daily lives, it triggers a stress response in our bodies. For example, imagine that you are about to cross the street and from out of nowhere, a car speeds around a corner. Seemingly without even thinking about it, you jump out of the way. You have your body’s stress response to thank for that.

The Stress Response System

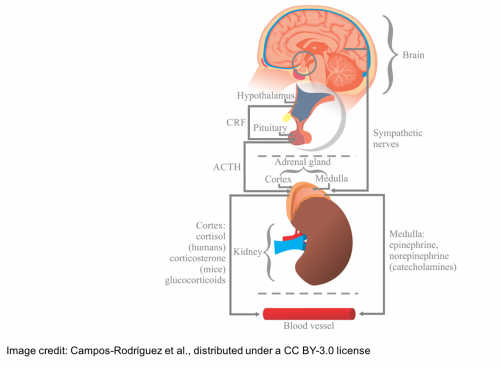

When we perceive a threat, a region in our brain called the hypothalamus sets off an alarm, triggering both the release of hormonal signals from the brain’s pituitary gland and neural signals. These signals, in turn, trigger the adrenal glands, which are located just above the kidneys, to release a sea of hormones. These hormones include both cortisol and adrenaline and they trigger a widespread response throughout our bodies.

During stressful situations, our hearts beat faster, our blood pressure rises, and our energy stores increase. For example, energy is made available to our muscles to help us jump quickly out of the car’s path.

Our body’s immune system, digestive system, and reproductive system are suppressed so that more energy is available to our bodies to deal with the potential threat.

Typically, our bodies regulate this stress response. Once the threat is gone, our hormone levels return to their normal level and blood pressure, heart rates, and body systems also return to baseline.

Impact on Development

But sometimes the perceived threat doesn’t go away. Imagine a child living with someone who abuses substances. This presents the possibility that there is always the threat of anger or violence, and the child’s stress response system stays active.

As adults, this chronic, long-term stress response system activation can lead to a host of health problems, such as anxiety, depression, digestive problems, weight gain, memory loss, and even heart disease.

In children, neural circuits involved in the stress response are still developing, and long-term exposure to stress can actually alter how the brain and body are wired. This can result in neural changes that can make it harder for children to concentrate, control emotions, and form stable, supportive relationships.

Combined with the other physical effects of prolonged exposure to stress, these early childhood experiences can have a life-long lasting impact.

We’ll talk more about these early experiences in the next section.

References

References

Alberta Family Wellness. (2014, October 16). Toxic stress. [Video]

Bales, D. (2014). Building baby’s brain: Buffering the brain from toxic stress. [PDF]

Campos-Rodríguez, R., Godínez-Victoria, M., Abarca-Rojano, E., Pacheco-Yépez, J., Reyna-Garfias, H., Barbosa-Cabrera, R. E., & Drago-Serrano, M. E. (2013). Stress modulates intestinal secretory immunoglobulin A. Front [Graphic]. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 7(86). [Online Article]

Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. (2015). Toxic stress: Key concepts. [Online Resource]

The Mayo Clinic. (2016, April 21). Chronic stress puts your health at risk. [Online Article]

Nachmias, M., Gunnar, M. R., Mangelsdorf, S., Parritz, R., & Buss, K. A. (1996). Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: The moderating role of attachment security. Child Development, 67(2), 508-522.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2005/2014). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain: Working paper No. 3. Updated edition. [Online Resource]

PBS NewsHour. (2015, June 27). How does the ‘toxic stress’ of poverty hurt the developing brain? [Video]

Thompson, R. A. (2014). Stress and child development. Future Child, 24(1):41-59.

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 13-1 Toxic stress. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]