11-1 Approaches to Learning

A – Preschooler Skills

Despite having developed an extensive vocabulary and sometimes even some impressive self-regulatory skills and strategies, children’s developmental journey continues well into the preschool years, and a preschooler’s social-cognitive world makes surprisingly large shifts and changes between ages 3 and 5.

Essential Readiness Skills

In the last lesson, we covered which skills are essential for school and community engagement and how children begin to develop those skills in infancy and early childhood.

Now we’ll consider how those skills develop in the preschool years. Preschoolers often get lumped into one group, but the differences between older and younger preschoolers can be vast.

Reflection Point

Take a moment to consider these differences and how they may affect one’s behavioral expectations.

Consider these questions:

- What learning and participation skills do you think preschoolers are developing?

- What skills and behaviors do you expect from older preschoolers that you don’t expect from younger ones?

B – Approaches to Learning

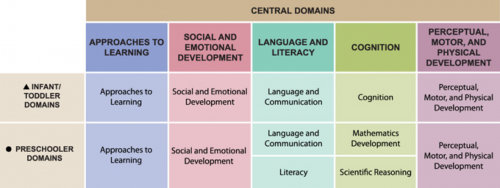

The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework (HSELOF) preschool Approaches to Learning domain has the same four subdomains as the Approaches to Learning domain for infants and toddlers does.

For example, the Creativity subdomain shows children’s growth from responding to adults’ prompts to express creative ideas to both communicating and applying their creative skills to tasks and problem-solving with and without prompting from adults.

The four subdomains within the preschool Approaches to Learning domain are: Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation, Cognitive Self-regulation, Initiative and Curiosity, and Creativity.

We’ll now briefly go over each of these subdomains. As we do, think about how each of these skills is intertwined in children’s learning and development.

Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation

One of the four Approaches to Learning subdomains is Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation. Being able to regulate one’s emotions and behaviors leads to greater social acceptance from peers and correlates with higher incidences of unprompted prosocial acts in later childhood.

As children develop in the preschool years, they will gradually be able to regulate their emotions and behaviors with greater independence from adult prompting.

At 3 years, children can generally follow simple rules and routines with reminders (sitting down or taking shoes off when asked to), handle classroom materials properly with adult support (reminders of where materials belong), and need frequent support from adults to manage their emotions, actions, and words (reminder to use gentle touches).

By age 5, children are able to follow rules, routines, and signals and know the rules when asked what they are. They can handle materials appropriately and clean them up, putting them in the correct locations. A 5-year-old will be able to use words and control their actions in response to challenging situations, such as resource sharing, with minimal support from adults.

Older preschoolers also typically show reduced aggression toward others and begin to understand the consequences of their behavior, including describing and predicting the consequences of their behavior on others.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom Tip to get more ideas about how to help build children’s emotional and behavioral self-regulation.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Guess Who!

Work together with your child to invent a story about people you pass on the street. Ask him/her, “Tell me about that man who just walked by.” See how he/she responds. You can help your child by asking questions like, “What do you think he likes to do for fun?” or “What is his favorite food?” Use your imagination!

Ages 3-4

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

As you and your child create a story, your child uses his/her communication skills to figure out what he/she wants to say and how, in order to be understood. He/She also has a chance to practice seeing through others’ eyes as he/she explores how different people might think or feel.

Does it make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how can you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

Context of Learning

The Approaches to Learning domain focuses on how children learn. Social and emotional development is often overlooked in the context of learning and academic achievement.

We’ve covered how children’s emotional and behavioral regulation skills develop and change in the preschool years, but why are these skills important for learning?

Join the conversation about the benefits of healthy social and emotional development. The learning benefits of emotional regulation skills include, but are not limited to:

- Better focus and attention.

- Lower cortisol, which allows for better retention of learned information.

- Better peer relationships, which helps children feel included and supported.

Reflection Point

Think of a typical learning activity in your early learning program and discuss how children’s skills in doing that activity will differ depending on their emotional and behavioral regulation skills. Consider these questions:

- What possible learning benefits will a child with more mature emotional and behavioral regulation skills have when doing that activity?

- How could you use that activity to support a child’s emotional and behavioral regulation development?

C – Developing Self-Regulation Skills

Cognitive Self-Regulation

Similar to infants and toddlers, preschoolers are continuing to develop their cognitive self-regulation skills.

At age 3, children frequently engage in impulsive behaviors and often need adult help to control those behaviors.

However, between 3 to 4 years, children begin to focus their attention with adult support, continue working on a task despite small challenges, and can complete simple two-step tasks from memory. Their memory abilities and brain areas are still developing, so instructions that involve more than two steps are difficult for them to retain.

Even with these new skills, you may find that younger preschoolers get distracted or forget the second step in less focused environments, such as a noisy room with many children doing different activities, or in the face of distractions, such as a new person entering the room, drawing their attention away from their current task.

Younger preschoolers also differ from infants and toddlers in their ability to switch gears on a task, such as trying a new way to open a box, when prompted by an adult. Children at this age are starting to respond to adult prompts reliably. This ability is critical for the development of creative problem-solving and task-switching.

Waiting and Persisting

By age 5, children are better able to delay meeting their desires, as indicated in their increasing ability to wait their turn, can independently maintain focus on an activity for up to 15 minutes, and can complete challenging tasks by persisting or seeking help from adults.

They are also beginning to remember some multi-step instructions. This behavior may not be consistent, but it will continue to develop as supporting brain structures continue to mature.

Older preschoolers are also better able to think flexibly and switch gears without adult prompting. One example is using indoor voices inside and outdoor voices outside. This helps them to navigate task transitions more calmly than younger preschoolers.

Video: Executive Function Skills (7:23)

The skills we have just covered are all included under the umbrella term executive function skills, which we discussed briefly in Session 10.

Let’s watch a video called Executive Function Skills. Dr. Juliet Morrison from Washington State’s Department of Early Learning and Dr. Gail Joseph, associate professor of educational psychology and director of Cultivate Learning and the EarlyEdU Alliance at the University of Washington, explain executive function skills.

This video is an excerpt of a longer webinar by the former National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning.

Play and Self-Regulation

One way to support children’s self-regulation and executive-function skill-building is through play. Play provides a context for social growth, learning, and exploration (and makes kids happier, too).

There are many kinds of play, including social or cooperative play, object play, pretend play, and physical or rough-and-tumble play. Instances of social, cooperative, and pretend play surge during the preschool years. Children are now paying extra attention to their peers and attempting to engage them in play behaviors.

Through these play activities, children are learning a wealth of developmental skills, such as strategies for approaching others, social consequences, social problem-solving, and strategies for self-regulation. Play offers a myriad of opportunities to practice social skills and communication, build relationships, and try out ideas in a safe and protected way.

When preschool-age children engage in dramatic play, they learn how to see others’ perspectives and practice communicating thoughts and feelings. Through cooperative play activities, such as building blocks or trains, children learn how to coordinate their actions with others and how to navigate social exchanges. Differences of opinion or planning typically arise and provide opportunities for children to learn how to solve social problems.

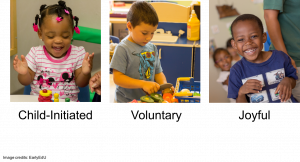

What Is Play?

What is play? How is it different from other childhood experiences? While we probably all have some idea about what constitutes play, it is, in fact, a complex and multi-faceted endeavor.

Researchers commonly use three characteristics to describe play:

- First, the child often initiates it. When someone else initiates an experience, it can become a moment for instruction rather than play.

- Second, play is voluntary. If a child is required to do something, even if it’s an enjoyable experience, it is often no longer considered play.

- Third, play is a joyful experience for the child. If the child experiences stress or discomfort, they are no longer playing. The joyful aspect of play is critical to its success as a learning experience. Joyful play conveys that the child is highly motivated by a positive force to participate at their highest level of achievement.

Since play is both voluntary and child-directed, it is highly individualized. The joyful part of play motivates children to do their best and often encourages them to explore at the edges of their knowledge and abilities. These aspects of play make it an ideal learning tool.

In the context of play, children can learn new physical skills, try out new social roles, and attempt new and difficult tasks, all while staying within their own comfort zone.

Since children set the limits and levels of their play, observing children during play can be a key way to understand the developmental trajectory of a child in multiple domains.

Dramatic Play

Children develop:

- Self-control by staying in character.

- Working memory by remembering the context.

- Mental flexibility by adjusting their behavior.

Play, especially role play and pretend play, builds and promotes the development of children’s self-regulation and executive-function skills.

Pretend play may appear to be a relatively simple activity, but it requires a lot of self-regulation. Children must inhibit their behavior to stay in character. They also must remember the context they have created and are playing in. And they need to coordinate with others by adjusting their behavior or finding solutions to social problems.

Also, when children are trying to create solutions for social problems, they must be able to regulate their emotions. This is an advanced skill at any age.

In fact, research has found that curriculum that includes play-based learning outperforms other, more instruction-only programs in measures of self-regulation, such as self-control, working memory, and mental flexibility.

Reflection Point

Take a moment to think about what peer social interactions you’ve observed during play. Think about interactions you’ve observed between children during play. Think about the ages of the children, the location of the interaction, and the circumstances of the interaction.

For example:

I was watching one child get upset because another child picked up a toy they were planning to use in their pretend castle. The child who picked up the toy then handed it back to the one who was crying. This illustrates a child practicing inhibiting their emotional response—the second child could have cried, hit, or yelled in response, but they didn’t. Handing back the toy meant that they delayed their desire to get the toy and exercised mental flexibility by changing what they were going to do.

Consider this question:

What social, emotional, and cognitive self-regulation skills were children practicing during those social interactions?

D – Practicing Mental Flexibility

Rule-Based Play

In addition to providing many opportunities for dramatic free play, rule-based games like Simon Says, Red Light Green Light, or Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes are terrific ways to help children practice their cognitive skills.

These games all require behavioral control. They must use:

- Working memory: Children must remember the rules of the game

- Attention: Children must pay attention to what the instructor or game leader is saying and doing.

In fact, recent research has found that how well children played a game that required these skills in kindergarten predicted growth across academic domains.

You can even use these games to practice mental flexibility—being able to switch tasks—which requires both emotional and cognitive self-regulation.

E – Code Switching

Rule-Based Games

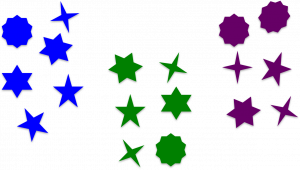

Remember the activity from before (lesson 9) where you sorted these shapes into different groups?

Some of you grouped by color. Others may have sorted by shape. Still others may have seen both ways to sort.

What other groups, such as sharp edges versus rounded, can you think of?

Sorting and categorizing games like this work much the same way that the other rule-based action games, such as Simon Says, work.

Children must consider one rule first, such as sort by color or touch your nose, when the educator says, “Simon says, touch your nose.” And then they need to consider another rule, such as sort by shape or do not touch your nose, if the educator does not say, “Simon says,” first.

These types of rule-based games help children learn to recognize and switch between two sets of rules. This helps to build cognitive flexibility—a part of executive function.

Switching the Rules

Let’s play another game that helps build executive function and self-regulation skills.

Interactive: Head and Shoulders

Interactive: Head and Shoulders

To give you an idea of what it feels like to work out your executive function, we’ll play an altered version of the game Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes.

Activity Debrief

Activity Debrief

How did it go? Did you find that activity easy or difficult?

Why it matters

Researchers asked children to play this same game to measure their executive-function skills, including:

- Inhibitory control—A child must inhibit the dominant response and do the opposite of what the adult says.

- Working memory—A child must remember the rules of the task.

- Focused attention—A child must focus attention on the directions that the adult gives.

- A recent study found that how well children did on this task in preschool predicted growth in mathematics. Children’s level of proficiency at this game in kindergarten predicted growth in all academic outcomes.

A recent study found that how well children did on this task in preschool predicted growth in mathematics. Children’s level of proficiency at this game in kindergarten predicted growth in all academic outcomes.

Video: The Timer (2:47)

In the video, The Timer, let’s look at an example of a child using executive-function and self-regulation skills in an early learning environment.

As you watch the video, think about: When are the children building executive-functioning skills, including maintaining focus, persisting in an activity, and flexibility in thinking and behavior?

Video Debrief

What skills executive-function skills were children working on? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answers

Examples are:

- Attention and Focus—Filtering out ambient noise and responding to an educator while remembering where they were in their pretend play together.

- Persistence—Continuing to play despite interruptions.

- Flexible thinking—Responding to each other’s changing ideas of what the state of the pretend play world is. For example, when one child has said that it is nighttime, the other responds by whispering. Then when the whispering child decides that it is daytime, the other child responds by waking up the animals.

An additional question to think about: How might you expect younger students to behave differently? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answer

Younger students might be more distracted and unable to react as quickly when peers change the pretend story line. This could lead to disagreements about their pretend play.

F – Executive-Functioning Skills

Initiative and Curiosity

Just as with infants and toddlers, the Approaches to Learning domain also focuses on other skills, such as initiative and curiosity, that help children explore and learn about their world.

By age 3, children have begun to regularly show initiative in their interactions with familiar adults and to maintain engagement in tasks for brief periods without prompting from adults. Their focus and attention have improved, which helps them work independently for increasingly longer periods of time.

Between the ages of 4 and 5, children begin to show more initiative to engage in their preferred activities. They will also demonstrate an increased willingness and capability to work independently.

By age 5, children will regularly engage in independent activities. They will communicate their choices to both adults and other children, and they can identify and seek out the items they need to complete an activity or task.

Let’s walk through how the same task might look at different ages:

- Picture 3- to 4-year-old children who want to pretend to be king of a castle. Perhaps they’ll recruit a familiar adult’s help in finding a suitable castle or the crown and cape necessary to dress up as a monarch. Once they find these items, they may even play on their own for a brief of time.

- In contrast, 4- to 5-year-old children might bypass an adult’s help and find a crown and cape on their own. Once they find the items, they might play on their own as king of the castle for a longer period.

- Finally, by 5 years, children might decide that they want to make a crown for a scenario in which they play members of a royal family. They might then seek out scissors, paper, and glitter to make crowns for this activity. They might also try to recruit other children to be members of the royal family.

Curiosity

Along with their initiative, children’s curiosity continues to grow. It’s no wonder that many developmental psychology researchers call children little scientists.

Preschool children are increasing their knowledge-seeking behavior by asking questions.

Young preschoolers primarily seek information with the help of adults by asking questions or trying out new ideas after consulting with adults about their plans.

As they mature, children will establish more independent information-seeking behaviors. They may find a new rock or leaf and examine it in multiple ways on their own before asking an adult about the item.

They also begin to seek out challenges more often. They have the confidence to take on new experiences despite the difficulties. This is especially the case if children have the social and emotional confidence to take on challenges, plus confidence in their self-regulation skills.

Self-regulation skills reduce the stress associated with failure and this give children the tools they need to face increasingly difficult challenges.

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom Tip to get more ideas about how to help build children’s curiosity about the world.

Does it make sense in the context of an early learning environment? If not, how will you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Today’s To-Do

Talk back and forth with your child about the plans for the day. Talk about what you are having for breakfast, where he/she is going for the day, what you might do, and what he/she hopes to do today.

Ages 4-5

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

There is no better way to learn how to plan than practicing. When you give your child the chance to think ahead about the day, you invite him/her to call on what he/she already knows and apply it in flexible ways to a new situation.

Creativity: Communicating Ideas

Young preschoolers begin to express their creative ideas in words or actions with adults’ help.

For example, a child might want to build something out of blocks, and an educator might ask questions like this: “What do you want to build?” “How tall will it be?” “What is it for?” “Will animals live inside?” With these questions, educators help children convey their creative ideas.

As children mature, they gradually use these models of communication to more independently express their creative ideas.

By age 5, children can express their creative ideas independently and they begin to ask questions about activities, demonstrating how they are thinking creatively about them. Along with the development of their executive functions and mental flexibility, they begin to display creative problem-solving.

Creativity: Imagination

One specific creative arena in which children develop is in the use of their imagination.

Between ages 3 and 4, children often use imagination in play and begin to communicate imaginative thoughts and plans to other children and adults.

Between ages 4 and 5, children’s imagination becomes more complex. They develop elaborate stories with each other and adults during play.

By age 5, children’s imagination is seemingly boundless. They regularly engage in social and pretend play with other children. They use their imagination to turn everyday objects into magical tokens and fantastical beasts. They combine various materials to discover new ways to create works of art.

References

References

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2022). Code switching demo. University of Washington. [Video File]

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). The timer. University of Washington. [Video File]

Diamond, A., & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science, 333(6045), 959–964. [Online Article]

Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J., & Munro, S. (2007). Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science, 318(5855), 1387–1388. [Online Article]

McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Duncan, R., Bowles, R. P., Acock, A. C., Miao, A., & Pratt, M. E. (2014). Predictors of early growth in academic achievement: The head-toes-knees-shoulders task. Frontiers in Psychology, 5.

Ponitz, C. E., McClelland, M. M., Jewkes, A. M., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., & Morrison, F. J. (2008). Touch your toes! Developing a direct measure of behavioral regulation in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(2), 141-158.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start (n.d.). Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages birth to five. [Website]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning. (2013). Building executive function skills in children and adults. Front Porch Broadcast Series. [Website]

Vroom. (n.d). Vroom tips. [PDF]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 11-1 Approaches to Learning. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]