10-1 Approaches to Learning

A – Approaches to Learning

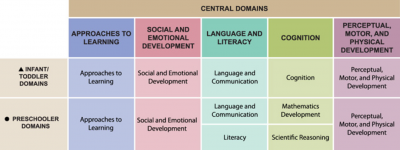

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework

The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework’s infant and toddler Approaches to Learning domain has four subdomains:

- Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation

- Cognitive Self-Regulation

- Initiative and Curiosity

- Creativity

This domain includes the development of skills that support children as they learn and explore their world.

For example, the Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation subdomain illustrates children’s growth from engaging with familiar adults for calming and comfort to using various strategies like removing oneself from the situation or seeking support from a familiar adult to help manage strong emotions.

We’ll now briefly go over each of the Approaches to Learning subdomains. As we do, think about how the skills in each subdomain are intertwined with children’s learning and development.

Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation

One of the four Approaches to Learning subdomains is Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation.

Emotional and behavioral self-regulation is an important school readiness skill. Being able to self-regulate in many different situations is an important aspect of becoming a successful learner.

In the early years, as children are starting to learn how to regulate their emotions and behaviors, they need assistance from adults, through responsive, back-and-forth interactions to build these skills.

From birth to 9 months, children will engage with familiar adults for comfort, to focus their attention, and to share joy.

Between 8 and 18 months, children begin to seek out closeness or look to a familiar adult to help them with strong emotions.

And by age 3, toddlers are developing more complex strategies for dealing with emotions, such as removing themselves from a situation, covering their eyes or ears, or seeking out a familiar adult for help and support.

Vroom Tip

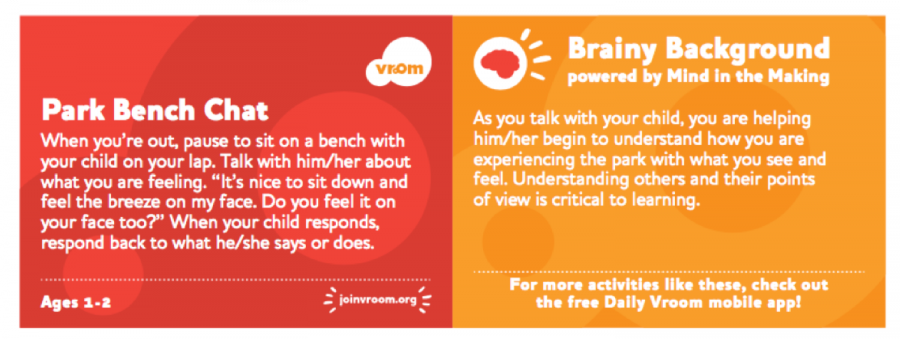

Check out this Vroom tip. It has ideas about how to help build children’s emotional and behavioral self-regulation.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Park Bench Chat

When you’re out, pause to sit on a bench with your child on your lap. Talk with him/her about what you are feeling. “It’s nice to sit down and feel the breeze on my face. Do you feel it on your face too?” When your child responds, respond back to what he/she says or does.

Ages 1-2

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

As you talk with your child, you are helping him/her begin to understand how you are experiencing the park with what you see and feel. Understanding others and their points of view is critical to learning.

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? And if not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

Responsive Interactions

Children, from birth to age 3, are also learning how to manage their feelings and behavior with the support of adults. They are beginning to develop coping strategies to manage feelings and behaviors during routine early learning program activities, such as playtime or times when they need to follow rules. Responsive adults can help children handle strong feelings and guide their behavior when they have conflicts.

For example, when an attentive caregiver responds, children between birth and 9 months are learning to calm down or stop crying.

Between 8 and 18 months, children begin to look to familiar adults for help or guidance with their behavior and actions. They may begin to self-calm by sucking on their thumb or fingers.

By age 3, children are developing more tools, such as being able to say “no” or “stop” rather than hitting, during conflicts. They are able to tell adults if they are tired or hungry.

Development in this area prepares children for important, everyday tasks, including participating in routines with the support of familiar adults, communicating about basic needs, managing short delays in getting needs met, and following basic rules for managing their actions and behaviors.

Reflection Point

We just talked about how children build emotional and behavioral self-regulation skills in the context of responsive caregiving. But what exactly is responsive caregiving? What does it look like and why do you think it is important for children’s emotional and behavioral self-regulation?

B – Developing Emotional Self-Regulation Skills

Children need a lot of support as they develop self-regulation skills. Children are not born knowing how to regulate their emotions or behavior, and we shouldn’t expect young children to know how.

Providing individualized, responsive care helps children feel secure. When children experience strong emotions, knowing that they have a responsive caregiver to help them manage those emotions sets the foundation for self-regulatory skills.

Children learn self-regulation skills by interacting with adults who model how to deal with their emotions and behavior, especially emotions like anger or frustration.

Verbalizing what you are feeling or describing actions you are taking to manage your emotions helps children learn. For example, if you accidentally spill a pitcher of milk and you feel yourself getting frustrated, you can verbalize your feelings, saying, “I am feeling frustrated because I spilled the milk and now I have to clean it up and change my shirt.”

Modeling ways to deal with strong emotions, such as going to a quiet place, also helps children build tools for dealing with their own strong feelings.

Talking to children about the emotions that they are having, and helping to label them, even from a very early age, helps children build the vocabulary and awareness they need to be able to verbalize what they are feeling and to seek help in navigating difficult situations.

C – Basic Cognitive Self-Regulation

Focus and Attention

In addition to emotional and behavioral self-regulation, children are also learning basic cognitive self-regulation skills during this period of development, including skills that allow them to focus their attention, persist in a task, and be somewhat flexible in their behavior and actions. Just like emotional and behavioral self-regulation, these cognitive self-regulation skills are fundamental to children’s ability to learn. Let’s look at how these skills develop during the first 3 years of life.

Learning to maintain focus and attention is a skill that children are developing during the first 3 years of life. Between birth and 9 months, children are beginning to learn to filter out distractions in their environment to focus on important people and objects.

Between 8 and 18 months, children’s ability to attend to objects, activities, and people grows. By 36 months, children can maintain engagement with familiar people, maintain focus on a simple task for short periods of time, and pay attention to activities that they actively join or initiate.

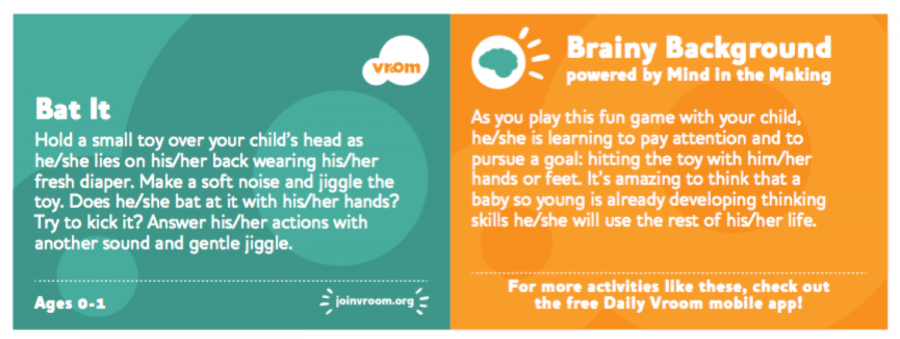

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip. It has ideas about how to help build children’s cognitive self-regulation in the area of reasoning and problem-solving skills.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Bat It

Hold a small toy over your child’s head as he/she lies on his/her back wearing his/her fresh diaper. Make a soft noise and jiggle the toy. Does he/she bat at it with his/her hands? Try to kick it? Answer his/her actions with another sound and gentle jiggle.

Ages 0-1

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

As you play this fun games with your child, he/she is learning to pay attention and to pursue a goal: hitting the toy with him/her hands or feet. It’s amazing to think that a baby so young is already developing thinking skills he/she will use the rest of his/her life.

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? If not, how can you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

Persistence

Children are also developing the ability to persist in their actions and behavior.

Over the first 9 months, children grow in their ability to engage in interactions with adults for more than just a short period.

Between 8 and 18 months, children start to show a willingness to repeat actions to solve a problem or repeat attempts to communicate with adults.

At about 9 months, when children are engaging in a task, they are able to pick the most appropriate action to solve a particular task. For example, let’s say one ball makes a sound when you squeeze it and another when you shake it. At this age, children are able to squish one ball to make a sound and shake another.

At 15 months, children will often want to complete a task on their own, sometimes resisting help. They are also able to persist in more complicated tasks that have multiple parts. For example, they might find the right block to fit into the hole of a shape-sorter toy and then continue until all the blocks are in the shape sorter.

By age 3, children are able to stay engaged as they work toward a goal or solve a problem. Even if the task is difficult, children often will try different strategies until they are successful.

Being able to persist in tasks, even in early infancy, influences development in other domains. For example, one study found that an infant’s ability to persist on a task at 6 months and 14 months links to a child’s cognitive development at 14 months.

Flexibility

Flexibility in behavior is another important skill that children are developing. Being flexible in behavior helps children to transition between activities and to deal with changes to their routines.

During the first 9 months, children often repeat behavior, trying the same actions over and over again. At this age, they may sometimes take a different approach when they are trying to solve a problem or engage in an interaction.

Children build on these early skills, gaining the ability to shift their focus, participate in a new activity, or try a new approach to solving a problem.

By 3 years, children are able to modify their actions or behavior as they solve problems, engage in social situations, and participate in daily routines.

At this point, children can transition to new activities that are part of their regular schedule and to some degree can adjust to changes in routine if they learn about it ahead of time.

For example, by age 3, children who are told in advance may be able to follow a new morning routine, such as leaving the house earlier to drop off a sibling, or adjust to a change in the afternoon routine due to bad weather.

Flexible Problem-Solving

Children also show flexibility in problem-solving. They may try more than one approach as they work to solve problems and engage with their environment.

Children’s problem-solving approaches change over time. In one study, researchers showed 2- to 4-year-old children a set of nested cups during a free-play session and then gave children a chance to play with a set of separated cups. The earlier play made them want to nest them, and children worked hard to solve the problem. They used a mix of strategies, which varied by their age.

A common strategy used by children younger than 30 months was brute force. When children placed a large cup on a smaller one, they would repeatedly twist, bang, or press down hard on the cup that didn’t fit. Another strategy the younger children used was to take apart all of the nested cups and start again if a cup did not fit.

Older children (30 to 42 months) used different strategies when a cup didn’t fit. They worked specifically with the non-fitting cup in relation to the set. For example, they took apart the stack at a point that let them put a new cup in the correct spot. Older children also showed a reversal strategy. After placing two cups together that didn’t fit, the child would immediately reverse them and try again. The younger group did not show the reversal strategy.

As children build skills, their ability to try new strategies to solve problems grows.

Executive Function

Many of the skills we have talked about so far, including self-regulation, the ability to focus and maintain attention, persisting in solving a problem, and flexibility in behavior or actions, are all executive function skills.

Executive function is an umbrella term for a whole host of skills, including:

- Focusing attention

- Motivation

- Decision-making

- Planning behavior

- Problem-solving

- Switching between tasks

- Organization

- Self-regulation

- Memory.

We will talk more about executive function next session when we discuss children’s development from 3 to 5 years. The foundations for these skills are set in the very early years of development.

Executive function skills are important for success in school and learning across domains. Self-regulation and executive function are strong predictors of academic achievement. For example, one study that followed children during the entire course of their education found that a child’s ability at age 4 to pay attention and complete a task were the greatest predictors of whether they completed college by age 25.

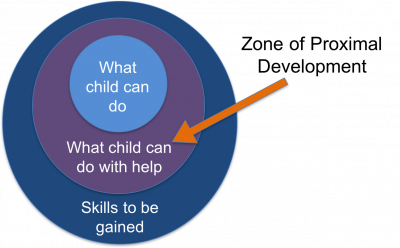

By scaffolding everyday interactions with children, educators can help children build these fundamental skills.

D – Developing Cognitive Self-Regulation Skills

Scaffolding

We’ve talked about scaffolding before in this course book. Scaffolding is a term that describes techniques adults can use to support and help children in their learning. Scaffolding is offering the right level of learning support to take a child’s knowledge to the next level. Just as a scaffold supports the construction of a building, adults can scaffold children’s experiences as they are learning.

In Session 1, we learned about the psychologist Lev Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. The Zone of Proximal Development describes a subset of children’s growing knowledge: the things that a child can do with help. Older or more capable people can help children acquire new skills by pushing them beyond their natural boundaries into this zone and helping them to expand their knowledge. When adults help children acquire new skills in this way, they are scaffolding children’s learning.

In Session 8, we talked about scaffolding children’s cognitive development. But what about skills like self-regulation or flexible thinking?

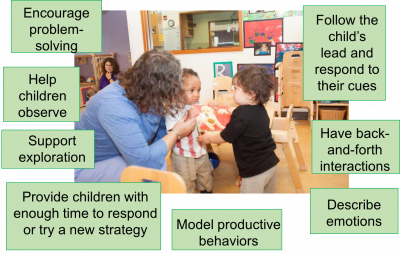

Tools to Scaffold Learning

Adults scaffold children’s learning by providing cueing, prompting, questioning, modeling, discussing, and telling. Using these tools, adults can stretch children’s learning to a new level.

Adults can help scaffold children’s emotional and behavioral self-regulation by describing their emotions and the emotions that they think children might be feeling. Adults can also model productive behaviors for children and talk them through challenging situations.

For example, in this situation, the educator may describe the boys’ emotions by describing how they both want the book and talking about their feelings of frustration. She may then model how the boys can sit and read the book together or help one boy give the book to the other. She could then help the first boy find something else to play with, modeling a self-regulatory technique of finding another activity when a situation is frustrating.

Adults can also help children develop their flexible thinking skills by supporting them in their exploration of the world and asking leading questions.

As children puzzle through new experiences, it is important to wait and give children the chance to respond or try a new strategy on their own. Giving children time to process helps them focus on the task and gives them the opportunity to develop their unique strategies to solve a problem.

Video: Exploring Shapes and Sounds (2:09)

The video Exploring Shapes and Sounds focuses mostly on the interactions of one child and educator, although another child joins the activity toward the end of the video.

Let’s look at an example of an educator scaffolding children’s exploration of different toys. As you watch, identify when children are building early executive functioning skills like maintaining focus, persisting in an activity, and demonstrating flexibility in their thinking and behavior.

While watching the video, think about the following questions:

- What did you notice?

- Which executive function skills were children working on, and how did the educator help support their learning?

- Is there anything the educator could have done to further their learning?

Video Debrief

Which executive function skills were children working on, and how did the educator help support their learning? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answers

- Attention and focus. One child was building attention and focus skills while working to stack the cups. The educator helped scaffold the child’s attention to the task by asking questions about the cups when the surrounding environment was distracting. The educator also helped the child transition to a new task—playing with the balls. Even though the child switched tasks, the child was still maintaining focus. The educator helped the child engage in the new task and explore the different properties of the balls.

- Persistence. The one child persisted in stacking the cups, even when the child couldn’t quite figure out how to fit one inside the other. The educator provided scaffolding by asking leading questions to help the child think about what other strategies to try.

- Flexible thinking. The same child tried multiple strategies while playing with the cups, trying different shapes and sizes. When the child shifted attention to the balls, the child also experimented with different strategies, trying to figure out the best way to make noise with them—shaking or squeezing. The educator supported the child’s learning by making observations that helped the child think about what was happening and providing suggestions for other strategies to try like squeezing.

Is there anything the educator could have done to further their learning? (click to toggle expand or collapse)

Possible Answer

The educator guided the child’s learning in a busy environment. Given all the activity in the room, the child might have benefitted if the educator slowed down a little, waiting longer before asking a new question or suggesting a new strategy.

E – Exploring the World

Initiative and Curiosity

Children use gestures and other strategies during this period to begin to resist things that they do not want or like. While this behavior can be challenging at times, it is an important part of children’s development as they learn to express their unique tastes and preferences in the world and begin to establish agency.

By age 3, children are often eager to try new experiences and attempt new tasks with or without help from adults; they have clear preferences and are able to make choices.

Interactive: Initiative and Curiosity

Interactive: Initiative and Curiosity

This is an interactive! Use the arrows on the interactive below or click on each label on the timeline to explore the actions of a baby born in September 2018.

Growing Curiosity

Children’s curiosity also grows during this time. Children’s early curiosity is expressed as they excitedly engage in back-and-forth interactions with an adult or as they interact with their environment, perhaps batting a dangling toy with their feet.

As children grow, they show more focused interest in their surroundings. For example, the child in these images is carefully examining the leaves, touching them, and perhaps trying to pull one off the plant.

Children may start to notice other aspects of their environment too. They may closely listen to a new song playing on the radio or explore a new piece of furniture.

By age 3, children often actively participate in new experiences, ask many questions, and enjoy experimenting with new materials or activities.

Creating engaging environments for infants and toddlers to explore helps foster their growing curiosity about the world and how it works.

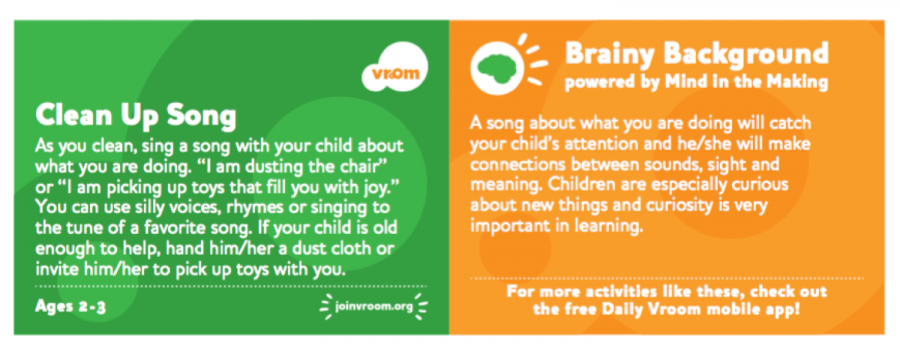

Vroom Tip

Check out this Vroom tip. It has ideas about how to help children build curiosity about the world.

View text-only alternative of this Vroom card

Clean Up Song

As you clean, sing a song with your child about what you are doing. “I am dusting the chair” or “I am picking up toys that fill you with joy.” You can use silly voices, rhymes or singing to the tune of a favorite song. If your child is old enough to help, hand him/her a dust cloth or invite him/her to pick up toys with you.

Ages 2-3

Brainy Background powered by Mind in the Making

A song about what you are doing will catch your child’s attention and he/she will make connections between sounds, sight and meaning. Children are especially curious about new things and curiosity is very important in learning.

Does this tip make sense in the context of an early learning environment? If not, how might you adapt the activity to better fit that environment?

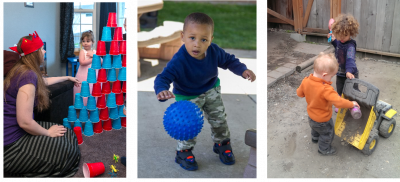

Engaging Environments

Environments that support creativity and exploration for infants and toddlers include materials that are varied, open-ended, and relevant.

Having a wide variety of materials that are open-ended can deepen learning. Choose materials that can be used in many ways and allow for creativity, investigation, and problem-solving. Varied materials provide opportunities for all children to participate.

For infants and toddlers, it can be helpful to intentionally group items near others so that children can mix and match them in their play and exploration. For example, a shelf might have nesting cups in one cubby, dolls or figurines in another, and a large basket of bandanas. Children may choose to nest the cups or use them to feed the figurines. They may fill the basket with the items or use the bandanas to wash the cups. Mixing items like this creates many options for imaginative play and can be an especially helpful strategy for mixed age groups.

Providing materials that are culturally and thematically relevant to children is also important. Asking parents about what types of materials their children like to play with at home is an effective way to figure out meaningful items to include in play and exploration areas of the early learning program. Each child has their own set of unique experiences and items that are familiar. Culturally relevant items provide children with the opportunity to play with familiar objects and allow other children to learn about different cultures.

Materials that you provide do not have to be expensive. Recycled, donated, or handmade items provide just as rich a play experience for children as new or purchased items. Often these materials provide even better exploration and learning opportunities since commercial materials don’t usually encourage as much imagination or creativity.

F – Developing Creativity Skills

Creativity is the final subdomain of the Approaches to Learning domain. Children use their growing creativity skills to support and further their learning.

For example, from birth to 9 months, infants change their expressions, behaviors, or actions depending on the responses they get from the people they are interacting with.

Between 8 and 18 months, children will start to use objects in creative ways, such as using a hand towel to cover a baby doll or a plastic bowl as a hat.

Between 16 months and 3 years, children begin to combine objects or materials in new ways. For example, they may bring objects from the dramatic play area to the block center to use in their play. At this age, children are also excited about making or creating new things. Providing a variety of materials in close proximity, as we just discussed, provides opportunities for children to explore items in new and creative ways.

By age 3, children are often willing to try new experiences or activities and notice and pay attention to new objects in their environment.

Children also express their developing creativity skills through the creative use of language, such as making up new words or creating rhymes.

Imagination

Children’s imagination begins to grow during this period of development.

Imaginative behavior first appears as the child uses playful sounds, gestures, and words during interactions, songs, and games.

Children are also learning to use their creativity to make and build new things like complex structures with blocks or works of art from crayons, paper, and paint.

Between 16 months and 3 years, most children will start to use their imagination to explore possible alternative uses of objects and materials. Referred to as symbolic play, it takes form as blocks become a birthday cake, a stick becomes a fork, and a spoon becomes a brush for a doll’s hair.

Interactive: Symbolic Play

Interactive: Symbolic Play

This is an interactive! Use the slider to explore the graph.

As infants build their symbolic play skills, they are also building skills in combining mental representations of objects, actions, or relationships in their world into logical sequences.

Research suggests that the development of single-object play is linked to early language skills like babbling and the emergence of more complex symbolic behavior later in development.

References

References

Banerjee, P. N., & Tamis-Lemonda, C. S. (2007). Infants’ persistence and mothers’ teaching as predictors of toddlers’ cognitive development. Infant Behavior and Development, 30(3), 479-491.

Crais, E., Douglas, D. D., & Campbell, C. C. (2004). The intersection of the development of gestures and intentionality. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 47(3), 678.

Cultivate Learning (Producer). (2017). Exploring shapes and sounds. University of Washington. [Video File]

Deloache, J. S., Sugarman, S., & Brown, A. L. (1985). The development of error correction strategies in young children’s manipulative play. Child Development,56(4), 928-939.

Mcclelland, M. M., Acock, A. C., Piccinin, A., Rhea, S. A., & Stallings, M. C. (2013). Relations between preschool attention span-persistence and age 25 educational outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 314-324.

Orr, E., & Geva, R. (2015). Symbolic play and language development. Infant Behavior and Development, 38, 147-161.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages birth to five. [Website]

Vroom. (n.d). Vroom tips. [PDF]

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2018). 10-1 Approaches to learning. In Child Development: Brain Building Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]