14 Yuna Shin on Ruth Asawa

Yuna Shin is an interaction design student at UW. She is interested in applying the design and storytelling process to reimagine how we can create more inclusive and resilient systems. Currently focused on how design research methods and contemporary art practices and intervene as tools for speculation. Her favorite days are when she can mull over her ideas through writing or crafting.

Ruth Asawa (American, 1926–2013) was an Asian-American sculptor based in California. Born to Japanese Immigrants, Asawa spent time in interment camps. Later in life, she traveled to Mexico City to study Mexican and Spanish art that influenced her wire sculpting technique. She attended Black Mountain College to purse her art studies. Today she is most known for her airy wire sculptures and her activism in art education.

Part 1: A Reflection on Ruth Asawa’s Wire Sculptures

In the first part, I begin by delving into Asawa’s upbringing and transformative milestones that have informed her making process. I further comment and analyze the learnings from projects in Honors 211 course in a letter format in the second part.

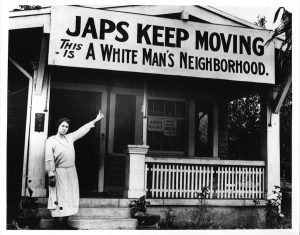

The more I read about the Japanese-American Artist Ruth Asawa the more I felt the relevancy of her artwork in terms of my own experiences as a Korean-American. An exploration into her work today reminds me of how little things can change over a few decades. Are we bound to make the same mistakes? It feels like it is. Is it destined that future generations will feel the same gut-punch I feel in unjust and discriminatory situations? How we must change, yet how little we do. Asawa’s artwork is here to outlast time for new generations like mine to continue this complex, wiry conversation.

Ruth Asawa From the Beginning: Not So Different From Today

Before her arrival to the Black Mountain College in the summer of 1946, Asawa was born in Norwalk, California. Her parents were immigrants from Japan and felt the pressures of discriminatory laws against the Japanese. They were unable to own land, become American citizens, or dream beyond becoming truck farmers (Asawa, “Life.”, N.D.). Asawa’s upbringing during the Great Depression with the stock market crashes led her family to struggle due to the unfavorable economy and persistent discrimination against Japanese. The immigrant struggle and climb to a top that felt ever-so at the brick of being a destination of illusion.

These moments of stillness at the farm, financial limitations, and traumatic dispositions due to discrimination stayed with Asawa throughout her artistic career. The bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in December 1941 led the United States to declare war on Japan (La Force, 2020). President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which led to the eviction of 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry in the West Coast and be placed in concentration camps (La Force, 2020). Her father, Umakichi, was arrested and sent to a Justice Department Camp in New Mexico during February 1942 (Asawa, “Life.”, N.D.).

For the second time, her family packed up their lives again to the Bayous of Arkansas and the Rohwer War Relocation Center. They were imprisoned with over 8,000 other Japanese-Americans. The prospects of a better future for the Asawa family was diminished. Rather the days were more in the present with little forms of delight. In the Arkansas soil, families planted gardens that thrived. Asawa’s mother socialized with other women at the camp and got her hair permed for the first time which were activities not accepted at their previous farm life (La Force, 2020). A focus on the little forms of delight from the mundanity of everyday life can be exemplified in her creative process.

Don’t Underestimate Seemingly Humble Materials: Black Mountain College

In 2021, there’s new levels of racism that people of Asian descent are experiencing (La Force, 2020). These experiences felt by Asian American communities in the United States is one that towers over individuals in silence. Asawa’s biomorphic-like wire sculptures reminds me that our emotions, however mighty and weak they may be, don’t have to be consolidated as something stiff and fear-inducing like metal wire. Rather, they can be transformed into an airy, dynamic, and hauntingly beautiful wire sculpture to be displayed for everyone.

Asawa did just that during her time at the Black Mountain College — quite literally taking her internal experiences and materializing then by expelling it outwards. She was eligible for early release from the concentration camp. This led her to enroll as a student in 1946 at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina and eventually study there for three years. A college where progressive ideals, experimentation, and individualized education was at the center rof the curriculum. Students were responsible for their own education (Asawa, “Black Mountain College.”, N.D.). During these formative years in her artistic career, she had influential teachers that impacted her making process. In a video interview, Asawa describes the influences of her artistic inquiries that she embarks on, “Bucky and Alber’s had a lifetime commitment not interested in ideas that were solved; they were only interested in ideas that didn’t have a shape yet” (Synder, 1978). The wire sculptures that Asawa became known for were nonexistent shapes that morphed into one entity to the next — giving shape to the abstract and messy.

Part 2: Further Revelations in the Making Processes

Dear Ruth Asawa,

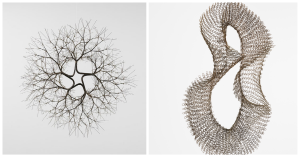

As I look at images of your iconic biomorphic-like wire sculptures I feel a rhythm in the craftsmanship. The repetitive and meditative motion of tediously forming an “inside out” shape with just one technique. I underwent a similar performative making process where it was just my hands and the tension that I pulled at that determined the fate of what I was making. The uneven and soft basket I made for the “Waiting Assignment” for class is similar in a voluminous sculpture made from one repetitive technique.

Right image: The artist forming a looped-wire sculpture in 1957. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham. Credit Imogen Cunningham; © The Imogen Cunningham Trust. From “Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa,” by Marilyn Chase, published by Chronicle Books, 2020

The basket with the soft t-shirt material protruding at the rim contrasts the tightly blanket stitched body that holds a quilt with a tessellation arrow motif. The black and white quilt reminds me of one of your early works at the Black Mountain College titled “Untitled (BMC, In and Out), ca. 1946-49 (Selvin, 2020). With my assignment, I wanted to emphasize the internal dilemmas we have while waiting — a feeling of a push or pull. Where were your arrow-shaped forms pointing or leading towards? What were you waiting for in anticipation while you painted this in your Black Mountain College studies? This repetitive geometry is seen throughout your work as you progressed in your career. The abstracting from materials in your work and my basket triggers the viewer to transport meaning for themselves into the works.

In your hanging wire sculptures, you push the limits of the material at hand. You simultaneously made the wire evoke a sense of coldness, danger, and rebelliousness. Whereas on the sculpture pictured on the right creates an illusion of motion, flexibility, and roundness. You mentioned in an interview how you let the material do the expressing while you stand back like a parent allows the child to express himself (Synder, 1978). There’s a rebellious quality to your art practice that can be connected to the Black Mountain College culture that you have the right to do anything you want to do. Who says this material has to be used for this purpose? The organic form of your sculptures resist the urge to conform. Similarly, my “Waiting” basket pulls back and resists the tug of someone as the quilt is being pulled out.

© THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA AND DAVID ZWIRNER Right image: Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S.066, Hanging Mobius Strip), ca. 1968.

© THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA AND DAVID ZWIRNER

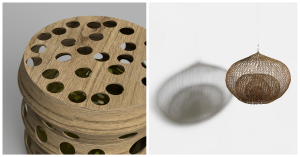

With my time capsule and “Waiting” basket sculpture that I made for class, I also focused on creating pairings that challenged the materials to simultaneously exist in more than one form. For my “Waiting” basket I used utility-purposed camping rope with soft neon knitting yarn. Together they formed a new shape and texture one that was firm and rigid yet malleable to the touch. The time capsule rendering I created uses an organic wood casing that holds a cold glass container in a perfect circle. The meaning each material beholds innately from the start is not confined by that one connotation. Your work displays the duality and mutli-faceted emotive qualities wire can have. You challenge what a utilitarian material such as wire often used for barbed wire fences like those at the concentration camp can be transformed into new imaginations.

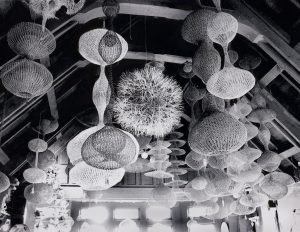

A shadow is casted behind your hand looped-wire sculptures when hung from the ceiling at a gallery. The quality of the sculpture transforms depending on the position you stand. In the absence there’s a new presence that forms. A common theme I see alive in your work is the seemingly limitless source of inspiration that can be found in the mundanity of everyday. As we wait for whatever may be on our minds at a single moment, there’s beauty around us in the present. You were able to find the in-between moments of delight and curiosity from the dry and soulless landscapes in New Mexico that you were raised on during your childhood years at concentration camps.

My time capsule also riffs off the unpredictability and fate of the present moment. When you leave the porous wooden sculpture outside in a forest the role of nature takes over. In the absence of human interaction and protection the time capsule takes on its own destiny. How far can the wood material itself go until it collapses and disintegrates into the soil? Conversely, how long before the shadow your wire sculptures create become hazy and nonexistent?

You also use this technique of starting from the inside and working your way outside when creating these wire sculptures. The result is a dynamic vessel that exists in multiple forms at once. The “Decaying Time Capsule” and “Duality” artwork I created also have components that rest inside an object. From the glass circle inside the wood casing to the arrow quilt tucked inside the basket, there’s an emphasis on how different components are interconnected.

My time capsule captures the written stories and thoughts of today. You distill your past childhood curiosities fueled by simple delights into your airy wire sculptures. The process of making ends in a product that documents a story. I see a story of resistance and persistence. A story of an Asian-American woman who followed the path of seeking ways to not only express her own experiences but those around her. This can be seen through her activism within art education. Despite barriers due to her Japanese ancestry, you continued to make strides by opening the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts.

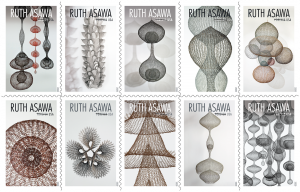

A resurgence in popularity has been occurring lately with your artwork. This is mainly due to the printing of your artwork on USPS postal stamps in the year of 2020. It was a year when the USPS was facing increasing pressure to stay afloat. The way tables have turned with your artwork saving the very system that put your family in concentration camps and discriminated against you because of your Japanese ancestry.

The photograph of the sculptures hanging from the living room of your Noe Valley home in 1995 showcases the breadth of sculptures you hand crafted. You never stopped creating or finding ways to nurture your innate passion for the arts. It might seem like you spent your childhood and early years waiting for the “American Dream” or a “better life,” but instead you were fully present. Just like the light and shadows being emitted from your wire-sculptures depending on the time of day and position you still remain despite any adversaries. It’s the ability to turn wire into characteristics that go beyond what it was intended for by conventional thought. It’s the hyper-awareness and calmness you channel through your works — transforming darkness into airy multi-dimensional organic wire sculptures where light can shine through.

I sense an artistic rebellion from your artwork that existed in a system where discrimination and racism thrived. A rebellion shaped by daring to live fully with every small pleasure casting its own shadow defining its own presence.

In wonderment,

Yuna

Citations

- Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. “Ruth Asawa.” Accessed February 28, 2021. https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/ruth-asawa/.

- La Force, Thessaly. “The Japanese-American Sculptor Who, Despite Persecution, Made Her Mark.” The New York Times Style Magazine. Last Modified July 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/20/t-magazine/ruth-asawa.html.

- Robert Synder. “Ruth Awawa: Of Forms and Growth.” Masters & Masterworks Productions, Inc. Filmed 1978. Video, 5:02. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T5eyKMEQizY.

- Ruth Asawa. “Black Mountain College.” Accessed February 28, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/life/black-mountain-college/.

- Ruth Asawa. “Life.” Accessed February 28, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/life/.

- Selvin, Claire. “How Ruth Asawa’s Pioneering Sculptures Ended Up on U.S. Stamps.” ARTnews.com. ARTnews.com, August 24, 2020. https://www.artnews.com/feature/ruth-asawa-who-is-she-famous-works-1202697634/.

Media Attributions

- “Japs Keep Moving – This is a White Man’s Neighborhood.” Ca. 1920, ourtesy of National Japanese American Historical Society.

- rom “Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa,” by Marilyn Chase, published by Chronicle Books, 2020

- Left image: In-progress picture; Yuna Shin, Duality, 2021. Rope, yarn, t-shirt, felt, and thread. Right image: The artist forming a looped-wire sculpture in 1957. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham. Credit Imogen Cunningham; © The Imogen Cunningham Trust. From “Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa,” by Marilyn Chase, published by Chronicle Books, 2020

- Left image: Quilt by Yuna Shin. Right image: Ruth Asawa, Untitled (BMC.95, In and Out), ca. 1946-49.

- Left image: Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S.452, Hanging Tied-Wire, Five-Branched Form Based on Nature), ca. 1965. © THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA AND DAVID ZWIRNER Right image: Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S.066, Hanging Mobius Strip), ca. 1968. © THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY THE ESTATE OF RUTH ASAWA AND DAVID ZWIRNER

- Row 1, 3, 4: Yuna Shin, Decaying Time Capsule, 2021. Digital rendering. Row 2: Yuna Shin, Duality, 2021. Rope, yarn, t-shirt, felt, and thread.

- Left image: Yuna Shin, Decaying Time Capsule, 2021. Digital rendering. Right image: The artist forming a looped-wire sculpture in 1957. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham.Credit…Imogen Cunningham; © The Imogen Cunningham Trust. From “Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa,” by Marilyn Chase, published by Chronicle Books, 2020

- Sculptures by Asawa hanging from the Douglas fir rafters in the living room of her Noe Valley home in 1995. Credit Laurence Cuneo, courtesy of the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner. Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa

- Ruth-Asawa-Forever-USPS