17 Alece Stancin on John Cage

Alece Stancin is a third year economics major in the Economics Department at UW. She is interested in researching economic inequality and the economic impacts on individuals from gender, sexuality, and race-based discrimination. She loves to write and has been trying many forms of making during the pandemic, including embroidery, watercolor, and learning to play the guitar.

John Cage (1912-1992) was an American composer, musician, and thinker. He taught music theory and performance at different universities, famously at Black Mountain College. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the twentieth century for re-imagining what music and composition could be.

Letter to the Artist

Dear John Cage,

Almost 75 years since you first visited Black Mountain College[1], its impact on you and your subsequent impact on the world is

still being studied. Here I am, proof of that. When I first saw one of your performances, “Water Walk,” I was immediately entranced. The first noise you made in the composition was through manipulating the strings of the piano rather than playing the keys. That is so utterly unprecedented that I had no idea how to react. When you started popping crackers, opening and closing the lid of a pot of boiling water, and scooping water from an actual bathtub at the front of the stage, I knew this musical performance would be like nothing I had ever seen before. As a pianist, I was in awe. I was ready to hear piano music carefully sculpted and scored. Instead, you broke every rule of composition.

I know you were thinking about the definition of composition and pushing its boundaries[2]. Once composition is not limited to music, where does it end? As you considered, is writing the act of composing words? Is dance the act of composing movement? Can scooping water out of a bathtub be composed on sheet music? For my “Waiting” project I created a spiraling labyrinth of footsteps to capture the tense, anxious type of waiting to hear if my grandmother is okay after injuring herself. I spent a lot of time on the placement of the footprints after cutting them out because I wanted to ensure that there was enough space to walk through the labyrinth without stepping on the footprint “boundaries.” I think the intersection of composition and visual art is interesting as area you did not explore as much. Perhaps I was composing emotions just as much as I was composing the physical space of the piece. I would love to know what you think about how I actively composed this piece of art.

Take, for example, Cecilia Vicuña’s basuritas. On her website, Vicuña describes her basuritas as “objects composed of debris” [3]. She arranged the pieces of trash and debris in a certain way to become a piece of art. Another word for compose is arrange. I think this is a clear example of the definition of composition expanding to include the composition of visual art, not just music. I imagine a painting can be composed, just as a poem or a dance is composed. I love this idea that you had and other artists have continued to expand upon.

When I think about what your expansion of composition did for music, I think about the new opportunities it created. Traditionally, music was something that was performed by a trained musician for an audience. The audience could include other trained musicians, but the important thing is that the trained professional was performing and the audience was listening. When you reimagined what music could be–the sound of a tea kettle, a dropped pan, disjointed piano notes–suddenly, the world of music became accessible to anyone. Nobody had to be a trained musician to create music; anyone who could create sound was composing. Music became an equalizer between the performer and the audience, and brought them together rather than dividing them into different planes of ability. How did you come to consider music in terms of sound rather than within the traditional concept of arranging notes played on an instrument? Did you know that it would create a whole new world of music and composition for anybody to participate in? Was that your intention?

Whether you intended it to happen or not, music has now become accessible to anyone who wants to participate, and your influence was part of that change. It reflects a broader change in the 20th century across disciplines of redefining who is an artist and what art is. Because of these movements, anyone who participates in creating can be an artist, rather than only people whose work is displayed in museums or played by orchestras. As a result, the distinction between “high” art and “low” art became muddy, to the point where the two are no longer considered separate. The larger trend of breaking down barriers to art is reflected in your work and has only expanded since your time.

Interestingly, one form of visual art that has always been accessible is sewing. Sewing was almost the opposite of music and “fine” art, where it has never had barriers, and only recently has been seen as art rather than a hobby or a utilitarian task. The AIDS Quilt and many of the women’s rights movement pieces were done intentionally with the connotation of sewing in mind: comfort, homeliness, women’s work. It is so important to recognize the work that has been done by the women’s rights movement, the AIDS Quilt, Cecilia Vicuña’s installments, and so many other artists in creating a space for sewing in the art world and showing that sewing is a legitimate field of art.

Breaking down barriers to accessing creation of art is what allowed me to create visual art projects for this course. I have no training in visual arts; the last time I made a visual art project for a class was in middle school. If art was still reserved for trained professionals, I would be resigned to the position of viewer rather than maker. Instead, I was able to create both a physical art piece and a digital art piece. The fact that I learned the digital art program during the process of creating my art piece does not make it less “true” or “fine” art; the only distinction is that with more training I could create a more intricate piece. As an economics major, I would not be able to participate in art classes and create art if the traditional definition of an artist had not been dismantled.

I can imagine this is a similar experience for people without musical training. At the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle, different simulated recording booths are set up to allow the museum visitor to play the drums, the piano, the guitar, and other instruments. A hundred years ago, this might have been strange. After all, most visitors to the museum are not trained musicians. But that is the whole point: nowadays, that doesn’t mean they can’t play the instruments and enjoy the experience. In the same way that I can create legitimate visual art as an amateur, untrained people can create legitimate music because of your work in redefining music. Although classical music training is not a possibility for everyone, playing music is.

This also makes me realize that so much of music and art is about the process rather than the end result, which is something that I think you focused on in your work: the composition, rather than the performance, is the essence of the work. Otherwise, why would you have spent so much time tinkering with the piano? You even became known for “preparing” the piano before playing it[4]. The concept of experimenting with the elements of the instrument itself in order to create new sounds and new ideas was foreign to me before I started learning about your work. The Dadaists intentionally used their instruments in new and “incorrect” ways as an act of defiance[5], but you did it to enhance the music, out of love and excitement for the new possibilities you created.

I am usually very end-result focused, and I didn’t realize how much my work would naturally evolve from idea to finished product. I rolled with the punches and allowed ideas to develop and replace one another in your spirit of focusing on the process. For example, in my sewing project, I originally imagined a spiral on a small scale, maybe 3 square feet, that would be hung on a wall. By the end, it had transformed into a full-scale spiral inspired by labyrinths that I can walk through. In fact, it isn’t actually finished; over the course of making it, I decided to leave it unfinished because the emotion of waiting that I represented is unfinished for me. It felt right to leave it uncompleted, but it was an idea that didn’t come to me originally. If I was not open to change, so many of the elements of the piece that I love now would be missing. It was new for me, and sometimes scary not knowing what my finished result would look like or even be.

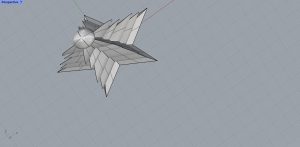

You began preparing the piano before you worked at Black Mountain College[6], but I have no doubt that you contributed greatly to that tenet of teachings at the College. Experimentation is something that I have learned to appreciate and try to incorporate into my art throughout the process of creating for this class. With my time capsule piece, my design abilities were somewhat limited by the tools I could use, so I tried to experiment with them as much as possible. Combining tools and using commands in different ways than I had seen in tutorials allowed me to create entirely unique designs that would not be possible if I used the tools individually. It was really freeing. I can only imagine that you felt similarly about how preparing the piano with screws and bolts felt similarly freeing for you, like a whole new world of possible sound suddenly opened.

I wish I could learn your opinion about Rhino and 3-D design, and just talk about how far technology has come from your era to now. We have digital keyboards now, which can make the keys sound like all different kinds of instruments. With just the push of a button, a keyboard can sound like an organ, or a full orchestra, or a clarinet, or a round of applause. Would you consider that to be a cheap form of composition, or would you say that electronic experimentation is equally valid to natural experimentation? Musicians also sample sounds in their songs, which I think is tied to the essence of what you were doing. In one of my favorite songs, in the chorus you can hear a train whistle, a bell on a bicycle, a car horn, and a doorbell, among other sounds. They are not meant to be a joke, but are instead genuinely incorporated into the song itself. I think you would enjoy that.

If I was going to revisit my projects knowing what I know now about your work, I think I would try to incorporate more experimentation and new materials into them. Although my projects went through a lot of change, they were still essentially the same at their core as they were when they were just ideas in my head. Really taking time to brainstorm, play with different ideas and materials, and embrace experimentation would only enhance them more and embrace the style that Black Mountain College embodied. Of course, I was limited by time and by budget, but my work in this class and everything I have learned about Black Mountain College and the Bauhaus has inspired me to potentially keep creating. I really enjoyed the process as well as seeing the final result, and my work was a really positive emotional outlet during these stressful times.

One of the things I admire the most about your work is how it seems like you often had no idea what was going to happen at the end of your experiments when you started them. It was not about the “correct” or perfect result for you; if we decide that every outcome is valid, then there is no such thing as failure, only different end results. We as creators are all end-result focused in a sense, because what we display for others is the finished product. If we could all embrace the idea that there is no failure in making, but only discovery, the opportunities for discovery would become endless, just as you learned when you first prepared the piano. We all still have a lot to learn from you.

In Admiration,

Alece

Media Attributions

- 9244714497_9705049417_w © Peter Sayers is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- project 2 © Alece Stancin is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Alece Time Capsule © Alece Stancin is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- “Composing Silence: John Cage and the Black Mountain College,” The Museum of Modern Art, last modified January 3, 2014, MoMA | Composing Silence: John Cage and Black Mountain College ↵

- Joan Retallack, “The Radical Curiosity of John Cage,” Contemporary Music Review, April 21, 2016, Full article: The Radical Curiosity of John Cage—Is the word ‘music’ music? (washington.edu) ↵

- Cecilia Vicuña, “Introduction,” Accessed March 14, 2021, Introduction — Cecilia Vicuña (ceciliavicuna.com) ↵

- John Cage, “How the Piano Came to be Prepared,” 1972, John Cage :: Official Website ↵

- Afsah Faheem, “Dadaism: Movement of the Rebels,” Taylor’s University, last modified September 21, 2020, Dadaism: Movement of the Rebels - + (kreatifbeats.com) ↵

- John Cage, “How the Piano Came to be Prepared,” 1972, John Cage :: Official Website ↵