15 Chelsea Shu on Gunta Stölzl

Chelsea is currently a senior studying Biochemistry and Global Health. Although she is working towards a career in medicine and social justice, she has always loved oil-painting, clay sculptures, and sketching. In the future, she hopes to use art to raise awareness about interpersonal violence.

Gunta Stölzl (1897-1983) was the first female master at the Bauhaus. She is known for her exploration of novel materials and incorporation of abstract art in traditional weaving practices.

Preface:

Gunta Stölzl grew up surrounded by nature. Born in Munich, Bavaria, Stölzl had access to sprawling mountain ranges that served as inspiration for her early endeavors in art. Her parents encouraged exploration, allowing Stölzl to wonder the world freely alongside peers[1].

After serving as a nurse during the first World War, Stölzl re-immersed herself in the art world by enrolling in Kunstgewerbeschule, an arts and crafts school in Munich[2]. Dissatisfied with the conservative gender norms at the school, Stölzl pushed for reforms in the curriculum2. Stölzl’s actions at the Kunstgewerbeschule was only the beginning of her reputation as a challenger of the status quo.

In 1919, Stölzl joined the Bauhaus for the institute’s progressive ideals. In the Bauhaus manifesto, the school promised reforms and equality in working environments to female students . However, when Stölzl walked into the school as a student, she was shuttled away to the struggling weaving department, the only sector in the Bauhaus that allowed women.

At the time, the Bauhaus was run by men that that believed weaving was “women’s work”[3], a hobby that can be mastered with little effort. The prevailing attitude is best captured by the quote stated by Bauhaus master Oskar Schlemmer: “where there is wool, there is a woman who weaves, if only to pass the time.” [3]

However, Stölzl believed weaving can be an art form. Unlike her male teachers, she viewed the practice as “the unity of form, color, and substance”[4]. Taking advantage of the department’s lack of structure, Stölzl spearheaded a new curriculum that challenged the boundaries of creativity in fabric. With the help of women like Marianna Brandt, Benitte Otte, and Anni Albers, she used the discriminatory policy to create an environment of experimentation free from male oversight. Stölzl began to incorporate Bauhaus artistic principles in fabric, creating abstract designs that were previously absent from the craft. Additionally, she also wove novel materials into pieces, including cellophane, metal, and fiberglass. Beyond the weaving machine, Stölzl also encouraged collaboration between different departments. Her spirit was exemplified in her 1931 Bauhaus article, where she stated: “The vitality of the material forces people working with textiles to try out new things daily, to readjust time and again, to live with their subject, to intensify it, to climb from experience to experience in order to do justice to the needs of our time.”2 Stölzl’s ambition led the weaving department to become the financial backbone of the Bauhaus and secured her position as the only female Master.

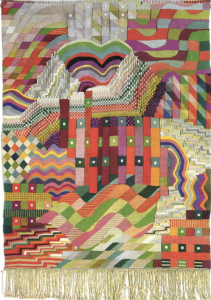

Stölzl’s style and creative process is best illustrated in her work Slit Tapestry Red/Green. Composed of cotton, silk, and linen, the tapestry illustrates a colorful and dynamic landscape, similar to the ones Stölzl drew in her youth. Furthermore, the contrasting colors allude to Johannes Itten’s teachings and the Bauhaus’ trademark style. Unlike other weavers in the Bauhaus, such as Annie Albers, Stölzl was not afraid to use bold colors alongside a mixture of materials. Overall, Stölzl’s tapestry serves as a landmark for her growth as an artist and her innovations in the weaving department.

In the finals years of the Bauhaus, Stölzl unfortunately faced numerous hardships. For instance, her position as a new working mother drew negative attention from her male colleagues, who believed she should have abandoned her professional career to raise her family2. Furthermore, with increasing Nazi influence over German politics, Stölzl’s Jewish nationality became a safety concern[5]. Through heartbreaks and misfortunes, Stölzl left her position at the Bauhaus prior to its dissolution to continue her passion. In the late stages of her life, she ran her own weaving mill in Zurich, Switzerland.

During her lifetime, Stölzl’s incited revolutions within the textile and art worlds. She advocated for interdisciplinary collaboration and turned her struggles into breathtaking pieces. To her, “we people of today simply have not yet found the form for love and marriage; the same searching that is expressed in all of our work is simply the desperate longing for a new way of life.”

Dear Gunta Stölzl:

I am writing to you a century since your time at the Bauhaus. In 2021, technology has advanced to a point where art as a practice has been redefined. Now, computer algorithms and virtual classrooms aid traditional art techniques to help us turn ideas into reality. Although we live in two completely different millennia, I felt a connection with your words and art. I think of myself as old-fashioned, preferring hands-on work over digital projects. I was enamored by the organized chaos in your designs and how you were able to use textiles to breathe life into your work. Additionally, I can relate to your struggles as a woman in a male-dominated industry. However, I am writing to you today to introduce you to my world while also asking a couple of important questions. To start, what did you mean when you said “the searching that is expressed in all of our work is simply the desperate longing for a new way of life”?

I. Art and Exploration:

When I read your quote, I interpreted it as a commentary on how art is a method of exploration. The animals I scribbled on printer paper in kindergarten ignited my curiosity for nature while the oil paintings in high school helped me navigate the twists and turns of adolescence. Each new art form I learned acted as a landmark for growth and maturity.

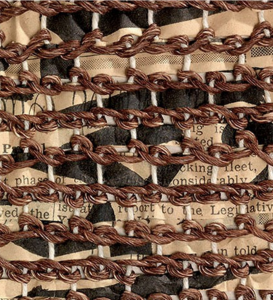

This was a project, named Smoke and Mirrors, I created for a class. The overall work centers around a ballerina trapped by broken mirrors. Similar to your creative process, I used this project to explore not only new materials but also new reflections on life. To start, I traded the familiarity of my paint brushes for pins and needles. I challenged myself to emulate movement through fabrics like you have done in your work. I chose to use materials from traditional ballerina clothing, including ribbons, tulle, thread, and fabric. Although I did not have as much control over the colors as I would have with paint, these materials introduced me to new textures and dimensions. I purposefully used frayed fabrics to inform the viewer of the work’s metaphor. The tulle I used furthered this sentiment. The overall composition of my work parallels your early paintings from the Bauhaus, utilizing lines and shapes to create a chaotic yet organized image.

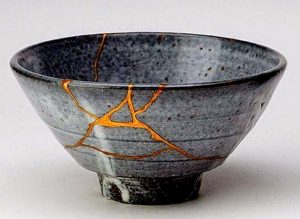

In addition to learning about new media, I also had the opportunity to reflect on my own experiences. Through Smoke and Mirrors, I wanted to tell a story of freedom. The piece was inspired my roommate, who has danced professionally for most of her life. Her dance career confined her within walls of mirrors, a glass prison that amplified her insecurities and forced her to pick herself apart. I believed her story paralleled how millions feel today amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. With my new understanding of fibrous materials, I illustrated this story through methods that would not be possible with paints. For instance, the golden metal thread used to stitch the mirror pieces was inspired by Kintsugi, a Japanese practice where people use gold to mend broken pottery as a metaphor for pain being the origin of beauty. In my piece, golden threads connect the shattered mirror pieces to show how these distorted reflections we see in ourselves, although painful, will ultimately lead to growth. The connections are scattered rather than collected, referring to how easily it is to overlook the growth we experience from our hardships. The thread added dimension to the story and allowed me to further the narrative surrounding dance. While you may disagree with the storytelling component of my work since you focused more on utility and abstract designs, I think you can appreciate my exploration of materials. After completing this project, I now understand that the “longing for a way new way of life” alludes to our explorations in not only the art world but also life. Did you ever use your pieces to tell a story? Did they help you process your hardships?

II. Art and Technology:

While I agree that art can be a form of exploration, I am curious to know if you think there is an end-goal to art. As an amateur artist in the 21st century and capitalist society, I have felt a constant pressure to produce even when I am uninspired. As a result, I have felt a loss of motivation on multiple occasions. I read about how your weaving projects were the main source of income for the Bauhaus. Did that ever feel exhausting? Did you at any point feel as if you were producing art just for monetary gain rather than expression? With burnout as a common phenomenon in my generation, people my age have turned to faster forms of art that can give instantaneous rewards. One defining example are memes. I think you may be confused on what exactly a meme is. In the words of Richard Dawkins, a meme is a unit of cultural information spread by imitation[6]. For my generation, imitation is just another word for humor.

Various Artists, Memes, 2021. Digital

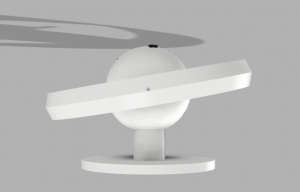

I wanted to encapsulate how memes have become an art form that defines my fast-paced generation. Thus, I utilized computer software, a key art tool today, to design a time capsule.

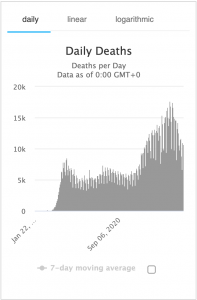

The main body of the time capsule is a globe orbited by the frame of a clock. The cylinders protruding from the center sphere are indications of time. However, instead of clock hands, I replicated the COVID-19 case statistics from 2020 to show the passing of time.

I wanted to fill the capsule with images of memes since they have been such a vital aspect of the virtual world and a defining component of my generation. During the creation process, I realized how, unlike weaving and painting, computer design software is less physical. As a results-driven person, I enjoy seeing my work come together. Even though I spent hours in front of my laptop hashing out the design, I still felt unsatisfied once the piece was complete since I couldn’t hold it. Considering the manual labor required in weaving, you would agree with my sentiment. Designing through my laptop made me appreciate the physicality of traditional art at a new level. I am also curious to see how people decades from now will react to memes as works of art. I believe your art pieces have withstood the test of time for their innovative concepts and designs, but I do not know memes can substantially influence art in the future. What are your thoughts?

My time capsule is only an instance of the vast possibilities technology has enabled in the 21st century. I think you would be overjoyed to see new ways artists have reinterpreted fabric creation and purpose. For instance, one of my favorite designers, Iris Van Herpen, has incorporated 3D printing into fabric work. Like how you collaborated with your peers in the weaving department at the Bauhaus to create new tapestries, Van Herpen works alongside artists, designers, and engineers to create unique fabrics made out of eccentric materials.

I also love Van Herpen’s work for its combination of STEM and art. Using computer software and 3D printing, Van Herpen creates fabric out of malleable and rigid materials. As a result, her clothing pieces display diverse motions, ranging from flowing silk to structured 3D-printed dresses, that would not be achievable through traditional fabric techniques. An artist that takes this sentiment to the next level is Neri Oxman.

Like you and Van Herpen, Oxman pushes the boundaries of fabrics. However, she achieves this by combining scientific principles. In 2013, Oxman created the Silk Pavilion, an artistic display created solely by silkworms influenced by the sun. Her idea resulted in an intricate geometric silk web that was completely calculated by math and biological principles . These women in art and science are able to achieve these incredible accomplishments because of change-makers like you, so I wanted to thank you for your efforts. If you were here today, would you explore these new technologies or would stay with traditional art forms?

III. Art and Social Justice:

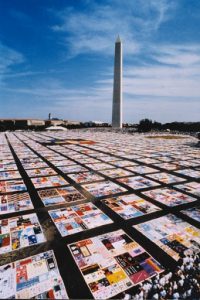

Beyond technology, art itself has also evolved drastically in the past 100 years. The most significant change, in my opinion, is accessibility. No longer constrained to the walls of elitist schools and social groups, art has become an expression that anyone can learn and share. With this phenomenon, people from across the world have reinterpreted the purpose of traditional art forms. For instance, when you were at the Bauhaus, people viewed weaving and fabrics as a tool2. Today, the practice acts as a catalyst for social change. A defining example is the National AIDS Memorial Quilt. In the late 1900’s, AIDS was a viral epidemic that devastated the LGBTQ+ community nationally. Due to stigma surrounding LGBTQ+ members, thousands passed away as a result of neglect from healthcare institutions. To honor the lives lost, Cleve Jones, a gay right activist, motivated fellow activists to create fabric panels for loved ones who died of AIDS. Jones then combined these pieces into a 54 ton quilt and displayed it in Washington DC. The project delivered a powerful statement that changed the minds of millions about the epidemic. As can be seen, with this new equality, art now holds tremendous social capital.

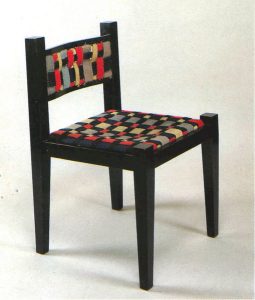

While the people who created these individual pieces may not have had your level of expertise, they worked alongside one another to achieve a common goal. Their collective efforts created an abstract work of art that almost resonates with the Bauhaus style. When I saw the arial view of the quilt, the image immediately reminded me of the chairs you created with Marcel Breuer. Although the scale of these two projects are vastly different, they share the commonality of being the product of collaboration. On one hand, you and Marcel brought together different departments within the Bauhaus. On the other hand, thousands of activists came together to honor a common cause. I believe working with one another in unity is a unique quality art possesses that transcends time.

IV: Final Thoughts

Throughout the past century, art has evolved in more ways than one. Accessibility and technology have both significantly improved, immersing the two of us in completely different worlds. On one hand, your works were completed with techniques passed down from masters and created for the purpose of utility. On the other hand, my pieces were created with expertise gained from virtual classrooms and brought to life for the sake of creative expression. However, our worlds still share common threads that have withstood the test of time. For instance, we both use our artwork as tools of exploration. Furthermore, art today is still grounded in your passion for innovation, except now it is pushing boundaries with the help of science and mathematics. Seeing your constant longing for growth, I know you would love how the art world has developed.

Sincerely,

Chelsea

Works Cited:

- “Women of the Bauhaus: Gunta Stölzl (1897-1983) – @GermanyinUSA.” n.d. Germanyinusa.com. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://germanyinusa.com/2019/03/07/women-of-the-bauhaus-gunta-stolzl-1897-1983/.

- Otto, Elizabeth, and RösslerPatrick. 2019. Bauhaus Women : A Global Perspective. London, Uk: Herbert Press.

- Weltge-Wortmann, Sigrid. 1998. Bauhaus Textiles : Women Artists and the Weaving Workshop. London: Thames And Hudson.

- T’ai Lin Smith. 2014. Bauhaus Weaving Theory : From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design. Minneapolis U.A.: Univ. Of Minnesota Press.

- Baumhoff, Anja, and Bauhaus. 2002. The Gendered World of the Bauhaus : The Politics of Power at the Weimar Republic’s Premier Art Institute, 1919-1932. Frankfurt Am Main ; Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Richard Dawkins. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- CDC. 2020. “COVID Data Tracker.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 28, 2020. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home.

Media Attributions

- Portrait of Gunta Stölzl, Photograph, 1920 © Bauhaus Kooperation is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Gunta Stölzl, Early Sketch, 1917. Pencil © GUNTA STOLZL BAUHAUS MASTER is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

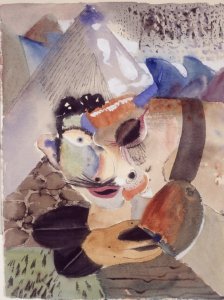

- Gunta Stölzl, Early Painting, 1917. Watercolor © GUNTA STOLZL BAUHAUS MASTER is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Gunta Stölzl, Slit Tapestry (Red/Green), 1927. String and Fiber © Bauhaus Kooperation is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Anni Albers, Study of Effect of Construction of Weave, 1929. String and Fiber © Bauhaus Kooperation is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chelsea Shu, Smoke and Mirrors, 2021. String and Fiber

- Gunta Stölzl, Diary Entry, 1920. Watercolor © Bauhaus Kooperation is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Kintsugi, Austin Cleon, 2016. Photograph © AUSTIN KLEON is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chelsea Shu, Close-up of Smoke and Mirrors, 2021. String and Fiber

- Meme, @FacebookUser0934, Digital © is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Meme, @FacebookUser264, Digital © is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Meme, @earringdealer, Digital © licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chelsea Shu, Time Capsule, 2021. Fusion360

- Chelsea Shu, Time Capsule, 2021. Fusion360

- COVID-19 Numbers, Center for Disease Control, 2021. Digital © CDC is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Silk Pavillion, Neri Oxman, 2013. Silkworms © MIT MEDIA LAB is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- The AIDS Memorial Quilt, NAMES Project Foundation, 1992. Photograph © NIH is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- The AIDS Memorial Quilt, NAMES Project Foundation, 1992. Photograph © NIH is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- The Colorful Weave Chair is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license