9 Sasha Mayer on Leo Amino

Sasha Mayer is an aspiring educator, more comfortable outside than in, and an artist, sister and friend. She studies Community, Environment and Planning at the University of Washington and is focused on the interactions between education, communities, policies and place.

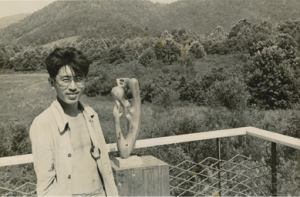

Leo Amino (1911-1989) is a Japanese-American sculptor who worked with a multiplicity of materials, including wood, resin, metal, thread, and plastics. He was a pioneer in using resin as a sculptural material in the United States. He taught at the experimental Black Mountain College during the 1947 and 1950 Summer Arts Sessions (one of three faculty of color to do so), instructing in wood.

Leo Amino-

When I first laid eyes on your sculpture work, I was instantly captivated. The forms are organic, flowing and balanced. Light, space, color and material are elegantly composed to explore spatial relationships. You were no stranger to innovation and combination of new materials. Wood, vinyl, resin, brass, thread and plastic all featured cohesively in your works, placed together so naturally it would seem they had grown up alongside each other. I was initially drawn to your art because it was simultaneously visually soothing and complex.

As an artist, your journey was informed by many things- an upbringing in Taiwan and Japan, immigration to the United States, a university and arts education, World War II and two summers at Black Mountain college, to name a few. As an immigrant from one place of strong nationalist agenda to another, you may have often felt an outsider in both traditions, disillusioned from the conformity and restrictions they encouraged[1]. As a member of the Black Mountain college faculty during the Summer Art Sessions, principles of open experimentation and a rejection of traditionalism and conformism likely drew you there. Your own work consistently rejected traditional sculptural forms in search of something more.

Processes of Making

You were not one for planning per se- in general you did not keep sketchbooks nor block out sculptures before setting out to carve them. I can relate to this desire for working on impulse and inspiration rather than planning. My creativity and thought processes associated with making are often stifled by too detailed a plan. I guess I would consider my approach to art reflective of life, in that real life is organic and impossible to predict. I think you and myself share this understanding, seeing possibilities and chance in the spaces that plans would otherwise fill.

When you worked with wood, the making process was about progression and the flowing of the design into existence, rather than the carving away of the whole as form slowly emerges[2]. The final pieces are deliberately smoothed and polished to hide traces of the tools used to shape them. The good craftsman- you and one of your first mentors, Chaim Gross, agreed- “uses the fewest tools and learns to know them”[3]. Products are visually detached from the process in much of your work beyond wood as well. The eye traces the flowing forms, the lines, the positive and negative spaces of your multi-material sculptures and wonders, how did such a composition come to be?

This is a difficult question to answer, as little record exists of your making processes, particularly with experimental materials like resin. I do know that your home was frequently your studio. You once used a baking sheet as a mold for the resin sculpture Composition #25, and while working with resin you consulted local industry for information on temperature and recipe specifics[4]. Polyester resin, at the time when you began experimenting with it, was an industrial material. Casting resin involved pouring liquid starting material into a mold, allowing gravity to fill all the crevices, and then curing it by introducing a chemical catalyst that generates heat internally and hardens the cast[5]. The process of casting resin is very technical, and this adds meaning to your work by further questioning the common perception of a nature-technology binary. When the technical process of casting resin is combined seamlessly with wood carving to create very biomorphic results, we see that technology (here the technicality of resin) is informed by nature for the purpose of reproducing natural forms. After all, it was naturally occurring resins such as amber that inspired synthetically produced resins. Sculptures such as Interplay #11 and Winter Scene exemplify this fusion of making processes.

Experiences of Making

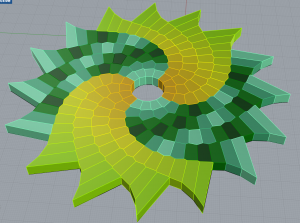

You embraced the exploration of new mediums and celebrated the inherent qualities of your materials, yet also espoused the idea of using few tools well in your early years working with wood. I wonder what you would think of the digital age of design. Computer aided design (CAD) programs have taken the world by storm, providing a countless number of tools for arriving at one’s destination. When I was designing a time capsule using CAD, I had to learn the craft as I practiced it, watching step by step instructional videos and surfing user forums. I copied the actions and processes of others to learn, and the smoothing aspects of the program itself created much less opportunity for a learner’s small flaws and mistakes to be recorded. At the same time, using the more complex parametric tools provided by Grasshopper allowed for input of unique data and the output of unique forms, despite the copied algorithm. Ultimately this got me thinking- how does the act of copying change the value and meaning of process? I found that following the steps of others changed the making experience significantly from that of more traditional mediums. For an inexperienced digital maker like myself, precision came at the cost of making autonomous decisions about what function to execute or what tool to use. The process was also disjointed- as the architecture of the algorithm builds, the output does not make itself visible in a consistent way. The product in progress may go through many transformations before concluding in its final form. The making process through replication or imitation is changed, but I would argue it is no less valuable. This kind of making challenges you to think big-picture, to sharpen your attention to detail, to be aware of the act of imitation and to think creatively about how to ensure the project is still uniquely your own.

In comparison to CAD, textiles represent the “more traditional medium.” In my own experience of creating a wall hanging that embodied the feeling of waiting, needle, thread and fabric worked in cohesion and with rhythm. This is in stark contrast to my more disjointed experience with CAD. Additionally, when I was sewing, my precision was limited by the physical capabilities of my two hands but I had full autonomous decision-making in command of the needle and thread. Imprecision became an important piece of the making process. Given the history of textile-making as feminized labor, and it’s evolution into precise, machinated factory production, rejecting efficiency and painstakingly stitching by hand felt at times like a reclamation of the medium. For me, CAD and sewing created entirely different making experiences. I wonder if you experienced any of these feelings when working with resin in comparison to wood. Did you have similar thoughts about the non-rhythmic, technical process of casting resin and the instinctual, sensual process of carving wood? If so, you did something I have yet to do in my art- you combined the two different processes to make something revolutionary. When I try to imagine what it would be like to attempt to combine my own disparate mediums, textiles and CAD, I see that this is a useful comparison (for those of us living in the 21st century) to understand how innovative your work was.

Perception and Visibility

In your sculptural work there is a clear interest in light and use of transparent material, something that I appreciate. The pieces in Refractional #48 are geometric, weighty forms, but they appear weightless, capturing light, color and depth. They are not static, but are dynamic in the way that light itself is- the impression shifts and changes gradually with the viewing perspective as one moves around the piece. This is a beautiful thing to be able to capture in a work of art. As I worked on my Waiting project, my vision was to capture the motion of light in a similar way- to create something that is fundamentally connected to the place it is hung and changes temporally as the quality of natural light shifts throughout the day. In its final form, I am skeptical of how well my project created the effect I was hoping for, but it makes me all the more impressed with your Refractionals.

Related to light and transparency is the idea of visual perception. You had a fascination with vision, particularly as a philosophical problem of internal and external relation[6]. Are our perceptions of things we see constructed from what is already held in our minds, or do they represent what is physically there? And by extension, what is made visible in a sculptural work and what is not? Many of your sculptures seem to be inquiries into these questions. Viewers of your work today note how it reveals otherwise hidden or invisible beauty in an intimate experience between the viewer and the sculpture. It is interesting that visibility and invisibility are phenomena you contend with in your art, but they are also things that your art contended/still contends with. What I mean by this is that you, an artist who took sculpture to new places with exceptional skill, could be considered nearly “invisible” today. For example, you and Ruth Asawa- two pioneering Japanese-American artists- were both creating sculptures at the same time (she was a student around the time you were teaching at Black Mountain College). Ruth Asawa’s art has only come to wider recognition in the past fifteen years or so, and your work has remained even more invisible[7]. I think it’s important to acknowledge this fact and place it in a larger societal context. As a Japanese-American during WWII and as person of color in American society, the white supremacist mainstream art world was not made to elevate you or Ruth Asawa. It seems that you may have already known this, and been unconcerned with the visibility of your work because of it[8]. Writing to you from the future, I can say that generally neither the art world nor American society have structurally changed. Whether you would have cared for more visibility, or perhaps would not have wanted it coming from the world of “high art,” more people, not just the occasional art critic, should be seeing your incredible work. I continue to be enthralled by your sculpture and hope that this published letter may allow others to have the same experience.

Sincerely,

Sasha

Media Attributions

- Leo Amino at Black Mountain College © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Composition #25 is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Winter Scene is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Interplay #11 is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Time Capsule © Sasha Mayer

- IMG_1031

- IMG_8417

- Refractional #48 is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Refractional #48 is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- “The Visible and the Invisible.” David Zwirner, 2020. https://www.davidzwirner.com/exhibitions/2020/leo-amino-the-visible-and-the-invisible/press-release. ↵

- Harris, Ruth Green. “Artist and His Medium: How Chaim Gross and Leo Amino Regard Wood Sculpture and Its Problems.” New York Times, December 29, 1940. ↵

- Harris, Ruth Green. “Artist and His Medium: How Chaim Gross and Leo Amino Regard Wood Sculpture and Its Problems.” New York Times, December 29, 1940. ↵

- Zimmerli Art Museum. Zimmerli at Home - Leo Amino, 2018. https://sites.google.com/scarletmail.rutgers.edu/zimmerliathome/zimmerliathome/online-exhibitions/leo-amino. ↵

- “Thermosetting Polymer.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, January 15, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermosetting_polymer. ↵

- “The Visible and the Invisible.” David Zwirner, 2020. https://www.davidzwirner.com/exhibitions/2020/leo-amino-the-visible-and-the-invisible/press-release. ↵

- Yau, John. “The Art World's Erasure of a Revolutionary Japanese-American Artist.” Hyperallergic, November 5, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/577159/leo-amino-david-zwirner/. ↵

- Yau, John. “The Art World's Erasure of a Revolutionary Japanese-American Artist.” Hyperallergic, November 5, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/577159/leo-amino-david-zwirner/. ↵