16 Roshni Srikanth on Ruth Asawa

Roshni Srikanth is a freshman studying Informatics at the University of Washington. She is a student in the Interdisciplinary Honors Program and is the Director of Diversity Efforts for WINFO (Women in Informatics). She is interested in studying technology, its interaction with culture, and sustainability.

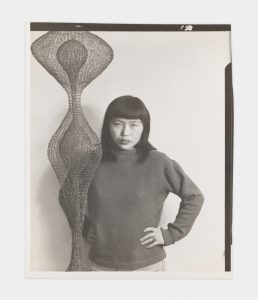

Ruth Asawa (1926 – 2013) was a Japanese-American sculptor who mainly worked using wire to create hanging sculptures. She was a student at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina and went on to become an advocate for art education in San Fransisco, where she helped found the San Fransico School of the Arts.

Dear Ruth Asawa,

My name is Roshni Srikanth and I am a freshman studying Informatics at the University of Washington. Currently, I am taking a class called “The Politics and Practice of Making: Art as a Tool for Creating Change”, and this quarter I had the chance to look at your life’s work and history, specifically in relation to what you learned at Black Mountain College. This letter is my attempt to connect some of the things I learned and created in this class to your philosophies in terms of artwork, looking at things through the lenses of history and education.

I believe that history informs the arts (and sciences) at almost every level. Whether it is the history of the maker, the history of the materials, the history of the content, or even the history of the method, the past often becomes one of the most interesting points of discussion for a work of art. Looking at some of your most well-known works, especially the wire sculptures, I can see the different histories come into play. I was especially interested in your use of wire as the material for the sculpture. I see in it parts of your own history, of being sent to a concentration camp surrounded by barbed wire, or of growing up on a farm playing in the dirt and seeing those same lines show up in the wire forms you would make later. I firmly believe that every artist carries their history into their work, and they can use their work to acknowledge or critique their past experiences to great effect.

In addition to how your personal history has impacted your art, I am also interested in the history of your materials. As part of my class this year, I created a piece inspired by the word “Waiting” and I saw some similarities between our inspirations and efforts. For my project, I chose to make a dhavani, which is a traditional pleated piece of fabric that is worn draped over the shoulder. I wanted this piece to represent how my feelings about waiting have changed over time, from something repetitive and boring to something carrying more weight and anxiety. In my work, I am also inspired by my own history and tried my best to represent my history and culture in my work. Much of that history is in the designs I chose to use, but also in how the finalized piece is supposed to be worn. The flower at the very top of the dhavani is a small rose, and a little hard to notice, but I wanted it to represent the outcome of the waiting – that there might be a long process to get to the flower but it will bloom eventually. When my piece is worn, the flower actually ends up behind the shoulder and out of the wearer’s sight to represent that we might not even notice the things we are waiting for right away, we need to turn and see them. The traditional Indian clothing that I saw daily was a big part of how I chose the specific elements of my project. The colors of the cloth and the border really tie into that because red and green are a really common combination in South India. I also took inspiration from mirror work on clothing found in North India and used CDs for my project instead.

I chose to present my work as part of a complete outfit. The first way is by laying it out on the bed, kind of like the outfit is waiting to be worn. The second way I chose to present it is by actually wearing the outfit and taking pictures in different places where I would wait. Sitting on the sofa looking out the window, and at the door waiting (but unable) to go outside. Below is the link to a slideshow of my “Waiting” project and a few photographs I took of the finished project.

One of the biggest limitations (that I imposed upon myself) was the fact that I only used materials that were ubiquitous objects around my house that were “waiting” to be used. As an example, the main piece of fabric that I used (the green blouse bit) was common in the way that blouse bits are often given as gifts to women attending various functions/celebrations. In this aspect of my project, I see some familiarity with your experiences too. The wire you use, seen as common, was because “[you] were so poor that [you] were taking materials that were around [you]… and using things that were natural rather than having good paper and good materials that [were] bought.” [1] My use of ordinary materials like old CDs, cloth, and your use of cheap wire can still create art because I believe art can be made out of anything, from milk cartons and wire to paint and hot glue, much like the Found Objects that were so common at Black Mountain. Furthermore, I believe that materials can also carry history with them based on their original use and their use in our artwork. Looking at your use of wire specifically, it is normally used as a barrier, to keep people and animals in and out of specific areas. However, in your artwork, the same wire takes on a different meaning. It is now used as something to allow light and air through, giving your sculptures an open, “lighter-than-air” look. Like the image below, allowing light through makes the piece feel as if it is floating, and the shadow also becomes part of the artwork overall.

In addition to the history of the crafter, and the history of the materials, I think there is also a lot of history involved in the process of making something. I have read about the inspiration for your wire sculptures, and about the local craftspeople who showed you how to make wire baskets. The process of manipulating metal into the new format of 3d sculptures carries history with it. To me, your process is similar to that of crochet. Looking at your work, I draw parallels to weaving and working with thread, creating natural forms that flow with smooth lines and curves. The similarities to textile work do not end there. Early textile work done by women was often not seen as “high” art and instead took on a more domestic/practical role. Unfortunately, the concept that artistic expression done by women is valid took a longer time to gain acceptance, as seen by the lack of much appreciation for your work, and its description as “domestic” or “decorative”. [2]In my experience, working with textiles is often also a repetitive and soothing task, where small stitches work together to create intricate designs and larger patterns. Similarly, your use of the looping wire is rhythmic and formed by repeated action. The larger sculpture takes on a life of its own and uses the small components for structure and pattern. The idea that small motions can work as a whole to bring life to a larger piece is something that never ceases to amaze me, especially when I see it in action. To me, this is also present in your work with community outreach. One example that immediately comes to mind is your work with the “San Fransisco Fountain”, where you worked with children in schools from different parts of San Fransisco to develop the carvings on the fountain. Each individual part, originally formed from dough, worked with the others to create a breathtaking depiction of life in San Fransisco.

Having learned so much about your life and work, I am inspired by how you continued to push through the blatant racism (which unfortunately continues today in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic), and sexism you faced in order to become a leader and expand the reach of art education in your community and beyond. I am interested in learning about your work with the community to expand art education because I am very involved in outreach myself. However, in contrast to your work with art education, the community outreach I was exposed to was primarily for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM). Reflecting on my experiences through the school system, I realize that my career path was primarily set by what I was exposed to as a child.

As a result of what I focused on while in school, I came into this class thinking that technology was for careers, and art was just a cool hobby – nothing more, nothing less. For most of the people around me, STEM and the humanities were (for the most part) mutually exclusive. However, the idea that someone needs to pick only one aspect and pursue that stands in direct contrast with the way real life works. I believe that the arts and humanities are beneficial topics for everyone to study, especially for people in technology. Studying the arts helps us to understand our own unique human perspectives and can help make our technology more ethical and sustainable in the long run. After taking this class, and learning more about art and its benefit to people, I can now say that I agree with your opinion that art education “makes a person broader”[3] and can help everyone criticize, commemorate, or understand our society in order to create improvements for everyone.

Sincerely,

Roshni Srikanth.

Media Attributions

- Ruth Asawa with hanging sculpture © Estate of Ruth Asawa and courtesy David Zwirner adapted by 2017 Imogen Cunningham Trust is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- “Waiting” © Roshni Srikanth

- “Waiting” © Roshni Srikanth

- Untitled (S.114, Hanging, Six-Lobed Continuous Form within a Form with One Suspended and Two Tied Spheres) © Ruth Asawa

- Ruth Asawa, “The San Francisco Fountain”, 1970, Bronze © Another Believer - Own work is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Oral history interview with Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier, 2002 June 21-July 5. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Zack Hatfield, “Ruth Asawa: Tending the Metal Garden,” The New York Review of Books, July 10, 2020, https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/09/21/ruth-asawa-tending-the-metal-garden/. ↵

- Milton Chen, “Ruth Asawa: ‘Art Is for Everybody,’” February 2, 2007, https://www.edutopia.org/art-everybody#:~:text=%22Through%20the%20arts%2C%20you%20can,the%20abstract%2C%22%20Asawa%20says.&text=Art%20will%20make%20people%20better,It%20makes%20a%20person%20broader.%22. ↵