6 Lucy Jiang on Ruth Asawa

Lucy Jiang (she/her) is a third-year studying Computer Science and Entrepreneurship at the University of Washington. She is passionate about designing, engineering, and expanding accessible technology to empower people of all abilities, and is involved in accessibility research in UW’s Human Centered Design and Engineering department. Outside of school, she enjoys baking and cake art, skating, hiking, and exploring Seattle!

Ruth Asawa (1926 – 2013) was a Japanese American sculptor and artist. She was one of the first Asian American students at Black Mountain College, and was widely known for her crocheted and woven wire sculptures and her public works, which reflect artistic influences from her cultural heritage. As a strong advocate for arts education, she contributed greatly to the creation and development of arts programs in her home city of San Francisco.

Dear Ms. Asawa,

Hope this letter finds you well! It’s hard to believe, but we’ve just passed the one year anniversary (if we can even call it that) of COVID-19 and quarantine here in the United States. This past year, a year of broken promises, crushed dreams, heartbreaking goodbyes, and false hopes, has given all of us much to reflect upon, both as individuals and as a society. Almost every day, I read about hate crimes committed against Asian Americans due to mounting division and paranoia due to the pandemic. Though society is certainly stronger together, right now, we are fragmented and polarized, speaking to echo chambers and avoiding accountability. There are certainly some parallels between the 2020s and the 1940s, despite the illusion of progress and growth over almost 80 years. After reading about your story, your work, and your legacy, I’m incredibly inspired by your resilience and pride in your identity in the wake of discrimination and I hope to learn from you to interweave these values with my own approach to art.

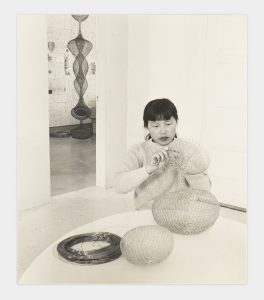

For this course, we were asked to create a project related to stitching and textiles for our midterm. Your world-renowned looped wire sculptures capture a similar concept – taking a traditional method of weaving and crocheting and using a different medium to add a new dimension to the artwork. You have described the texture of your sculptures as “a woven mesh not unlike medieval mail” (Ruth Asawa, “Sculpture”), and have alluded that the forms were inspired by your childhood memories of creating sketches of sculptural forms in the soil. You were first inspired to experiment with wire as a medium after a visit to Mexico. With the crocheted pattern in which you specialize, only the “shadow will reveal an exact image of the object” (Ruth Asawa, “Sculpture”) – indicating that the true magnitude of your hanging sculptures cannot be comprehended or appreciated until you step back and consider a part of the art on which you would usually never focus. I find it admirable that you were able to take such a rigid and sturdy material such as wire and transform it with textile techniques to become something that seems much more flexible, fluid, and dynamic.

For my midterm project, instead of creating a textile work, I created a cake that resembles an embroidery hoop with piped “embroidered” flowers that are on the cusp of fully blooming. Though this was a major risk, I was excited to channel something that I knew well into an art piece related to something that I was newly learning about. We’ve both adopted a stitching technique and transferred it to a different artistic medium with your sculptures and my midterm project. I find it interesting to draw similarities between our approaches to expanding upon existing textile methods. This project was incredibly thought provoking and enjoyable, as I was able to take something traditional and build upon it in an innovative way to create something new altogether.

One of my motivations for deviating from the assignment’s fabric requirement was because I thought it would be interesting to connect baking to embroidery work. Many textile projects in history have been used for activism, such as the AIDS quilt and handkerchiefs embroidered by women suffragists. I’ve also noticed a recent surge of using cakes and desserts as a medium to spread important messages on social media, showing another clear parallel between confectionary and embroidery. However, textiles can be preserved and honored in their original form in museums or as family heirlooms, serving as a persistent reminder of the textile’s message. Cakes, on the other hand, are temporary – no matter whether they are kept by the original artist, given to others, or kept in a museum, there is only so long before the cake begins to decompose. I speculate that photo documentation is the only way to capture and widely share cake art for activism, although using the cake as an incentive can be an effective way to spur people to action.

Traditionally, throughout centuries, both baking and embroidery are seen as a domestic activity and women’s hobbies, but the most famous pastry chefs and fashion designers are commonly men. In the modern day, this same dichotomy stands – women and other minoritized groups reclaim a method of craft to empower the people who create and benefit the most from their works, yet they receive minimal recognition and are rarely taken seriously or granted as much prestige as they should.

While creating the midterm project, I reflected greatly on the role of baking and stitching in the domestic sphere as opposed to the professional sphere, and it helped me think more deeply about my own role in reclaiming this medium for both myself and other women home bakers. When baking, not only do I enjoy the process, which I find to be thought-provoking and therapeutic – I also find pleasure and joy in sharing my baked goods with others to commemorate a milestone, to celebrate a birthday, or even just for no reason. In fact, despite being so temporary, desserts are often associated with major occurrences in one’s life, and they can often make a lasting impression. It’s always gratifying to see the smile on others’ faces when they receive baked goods, and this is one of the biggest reasons why I love baking and creating cake art.

When you create art, what motivates you? What makes you curious – what drives you to push the envelope and create something completely new? I know that you’ve mentioned that your “curiosity was aroused by the idea of giving structural form to the images in [your] drawings… These forms come from observing plants, the spiral shell of a snail, seeing light through insect wings, watching spiders repair their webs in the early morning, and seeing the sun through the droplets of water” (Ruth Asawa, “Sculpture”). In terms of shapes and forms, you seem to take lots of inspiration from nature, which is full of a multitude of coexisting geometric and random patterns, giving rise to your fantastical and unique silhouetted sculptures. But what would you consider to be the most gratifying part of the process? Would it be looking at your finished work and seeing its resemblance to the beauty of nature, or would it be knowing that you have created something new altogether, something that celebrates nature but can never emulate it?

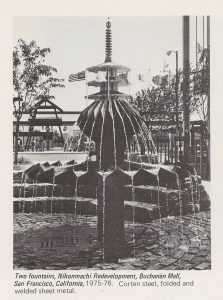

Furthermore, although you were most famous for your looped wire sculptures, some of your other well-known works of art are the Nihonmachi and Aurora fountains. Both of these sculptures feature a paper fold (origami) design inspired by your many Saturdays spent at Japanese Cultural School (Ruth Asawa, “Public Commissions”). In creating these public sculptures, you represented and paid homage to your own cultural heritage through your work, bringing to light the role of art as a cultural artifact as well. Not only are these sculptures beautiful, but they are a testament to your pride in your background, despite being of a nationality that faced unjust internment merely 30 years prior to the casting of these fountains. Out of curiosity, did you practice these origami fountain designs during your childhood? Or were they constructed by piecing together bits of memories of previous paper fold patterns?

As exemplified by my midterm project, most of my baked creations are western recipes, reflecting the country in which I was born and raised – my parents rarely used the oven when I was growing up, except as an occasional drying rack. Baking is an art form that I learned on my own, starting from inedible chocolate hockey puck muffins in 2013 and evolving into classical-art inspired cakes after years of trial and error. For me, the biggest sign that I had finally found my true passion was my desire to learn more. One example of experimentation and inspiration from Chinese traditions was a giant mooncake cake that I created in 2019, in which I used almond extract and cocoa powder to subtly recreate the nuanced flavor of lotus seed paste and used buttercream to achieve the details that adorn the top of a traditional mooncake. Though I don’t always incorporate my Chinese heritage into my baked goods, I constantly try to consider and seek out opportunities to syncretize these two cultures and meld them into one cohesive work. However, this is a constant push and pull, and there isn’t a day where I don’t feel a disconnect between my Chinese and American values.

As a first-generation Japanese American, I wonder if you’ve felt these internal conflicts too. Your sculptures, like the Nihonmachi and Aurora fountains, are clear examples of a successful and impactful integration of your Japanese and American cultures. That being said, I imagine that behind these bronze sculptures are a pile of scrapped designs, ideas that never saw the light of day because they didn’t quite capture the meaning you intended. Did you ever find these two aspects of your cultural identity clashing with each other? How were you able to grapple with this sense of cognitive dissonance to turn these thoughts into art, if you even did at all? Did disagreements between different aspects of your background ever impact your art and your approach to creating art?

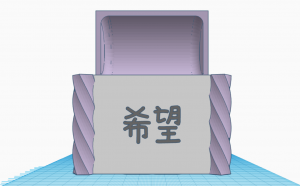

For my time capsule project for this course, I was inspired by both your work and my own cultural heritage as a Chinese American born in the United States. However, I found myself struggling to find the right words to say. Should I have said something in English, a language in which I feel more confident in expressing my true thoughts? Or should I have written something in Chinese, a language known for its four-word idioms that can allude to an entire story or myth with just four syllables? Ultimately, I inscribed the Chinese word for “hope”, 希望, on the front of the box – like your fountains, I was drawing on experiences and skills learned from my nine years of Chinese School while I was growing up.

While the onset of the digital age has made handwriting more and more obsolete (something that I experience with English, and much more so with Chinese), I find myself hanging onto these handwriting skills that once felt so familiar but now feel so foreign. As part of the project, it was quite odd to explore technology-aided hand-making with TinkerCAD – I was using an online program to handwrite Chinese characters. I was harshly scrutinizing every stroke, undoing and redoing each one multiple times before I was satisfied with my characters, alluding to the ideas of perfectionism with digital art that we’ve discussed in class. I’m wondering if you’ve ever felt that way too – did you feel like your experiences growing up in the United States took away from your Japanese identity? Did you feel as though you were losing touch with a part of your life?

Though I mulled over what to write on the box, at the end of the day, I believe that writing 希望 achieved my intended purpose – hope is a word that can convey a multitude of meanings to each different person who sees it. In creating art that celebrates my cultural heritage and my mother tongue, I’m able to reconnect with the customs, values, and memories that have shaped me into the person that I am today.

This concept of creating art that captures your background is something that I hope and believe will stand the test of time. Even 100 years from now, I hope that people are proud of their cultures and what makes them different, leveraging our different perspectives and insights to become stronger, together. Your ability to transcend cultural boundaries and honor your own background and identity as an Asian American artist is extremely inspiring, and in the future, I hope to be able to create and appreciate even more art that can speak to shared cultural experiences.

Lastly, another aspect of your legacy that resonates deeply with me is your commitment and dedication to expanding access to education, specifically arts education in the San Francisco Bay Area. Especially after being barred from obtaining your Bachelor’s Degree in teaching, and considering all of the other barriers that you faced in your educational journey, your resilience in the face of hardship and racism is evident through both your time at Black Mountain College and your lifelong advocacy efforts.

You were “a firm believer in the radical potential of arts education from your time at Black Mountain College” (David Zwirner), a mindset that led you to help open the first public arts high school in San Francisco, which is now named the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in your honor. Later in your life, I saw that you believed in this mantra: “learn something, apply it, pass it on so it is not forgotten” (Ruth Asawa, “Arts Activism”), tying into the idea behind our time capsules as well. You were able to incorporate your learnings from Black Mountain College into the Alvarado School Arts Workshop starting in 1968, a workshop program that provided arts education to young children. Through your personal experiences and benefits of working directly with professional artists, you believed that students should have access to this same level of immersion and exposure so that they could become “more highly skilled in thinking and improving whatever business one goes into, or whatever occupation” (Ruth Asawa, “Arts Activism”).

I wonder, if you were to go back in time to when you were at Black Mountain College, would you have recognized just how transformative and radical that experience was? Or did the true value of your arts education from Black Mountain College only become evident after the fact? Did you consider other occupations after Black Mountain College, or were you confident that art (and later, teaching art) was your true calling? Especially as a current university student, I think about this more often than I should – is my interdisciplinary education just one piece of the big puzzle that makes me, me? Will the memories that I placed in my time capsule turn out to be pivotal moments, or are they just treasured memories that have no impact on the ultimate direction of my life? Are these four years of my life deeply shaping who I am and will be, whether that’s through the people that I know, the activities that I’m doing, and everything that I’m learning… and I just don’t know it yet?

As one of the first Asian American women at Black Mountain College, you broke boundaries, pioneered new and creative forms of sculpture, advocated for access and equality in education, and inspired many women after you to do the same. You have shown that, even in times of division, it is possible to stay true to who you are and to celebrate your roots. It’s been extremely inspirational to be able to study your story and life experiences through this class, and I hope to honor your legacy as best as I can.

Thank you for showing us that we all have the power to sculpt our own path.

Lucy Jiang

Works Cited

- Artnet. “Ruth Asawa.” Accessed March 15, 2021. http://www.artnet.com/artists/ruth-asawa/.

- David Zwirner. “Ruth Asawa: Biography.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.davidzwirner.com/artists/ruth-asawa/biography.

- Johnson, Mark. “1976 and Its Legacy: Other Sources: An American Essay at San Francisco Art Institute.” Last modified September 11, 2013. https://www.artpractical.com/feature/other-sources/.

- Martin, Douglas. “Ruth Asawa, an Artist Who Wove Wire, Dies at 87.” The New York Times. Last modified August 17, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/18/arts/design/ruth-asawa-an-artist-who-wove-wire-dies-at-87.html.

- Ruth Asawa. “Arts Activism.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/life/arts-activism/.

- Ruth Asawa. “Asawa at Work.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/asawa-at-work/.

- Ruth Asawa. “Black Mountain College.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/life/black-mountain-college/.

- Ruth Asawa. “Life.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/life/.

- Ruth Asawa. “Public Commissions.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/art/public-commissions/.

- Ruth Asawa. “Sculpture.” Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ruthasawa.com/art/sculpture/.

Media Attributions

- Ruth Asawa working in her home © Imogen Cunningham

- 1956RuthLoopedWireSculptures © Paul Hassel

- FinalCake © Lucy Jiang

- WaitingProgress © Lucy Jiang

- 1986AuroraFountain © Hudson Cuneo

- 1975NihonmachiFountain © Carlos Villa

- TimeCapsule © Lucy Jiang

- 1960RuthSoloExhibit © Paul Hassel

- AsawaAtWork © Imogen Cunningham