Introduction

Jacob Lawrence in Seattle, 1971 / 2021

Juliet Sperling

Press play, and you’ll hear the sounds of the University of Washington’s Roethke auditorium on October 5th, 1978: applause, the muffled creaking of the stage as a speaker steps up to the podium, shuffling papers.

“I’m trying to hold that first slide…yeah, this one,” he says to the tech operating the projector, as the picture he wants appears on the screen. “I think we have it now.”

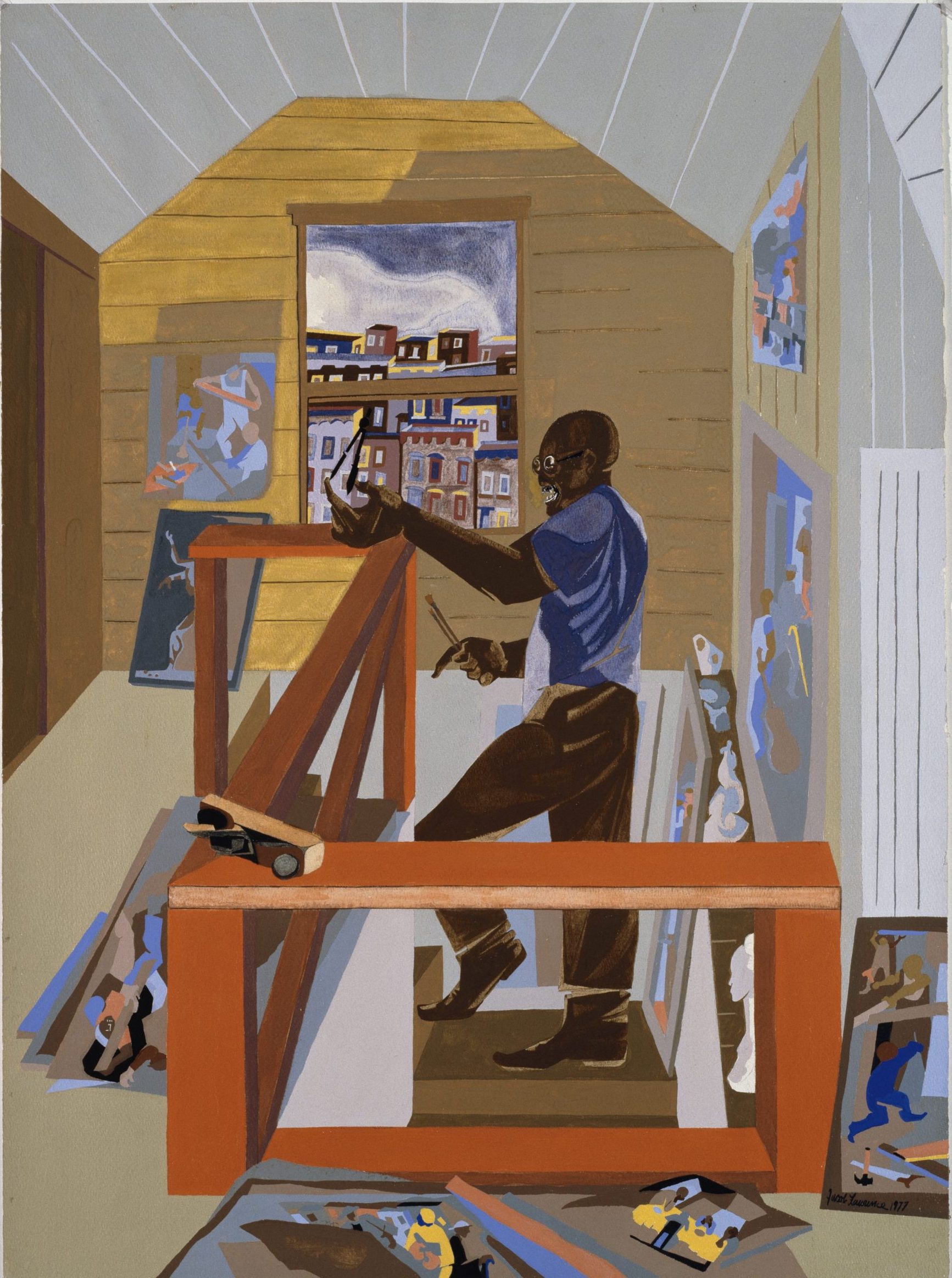

“This slide is one of my latest works,” Jacob Lawrence tells the audience. “[…] it’s my studio here in Seattle.” The 1977 painting, The Studio, shows the bespectacled artist in his workspace (fig. 1). He stands at the top of the stairs in profile, left knee pushing off the step as if mid-climb. A compass is balanced in his outstretched left hand, index finger pointing upwards; the right hand inverts the gesture, one finger pointing towards the floor as the others wrap around two paintbrushes.

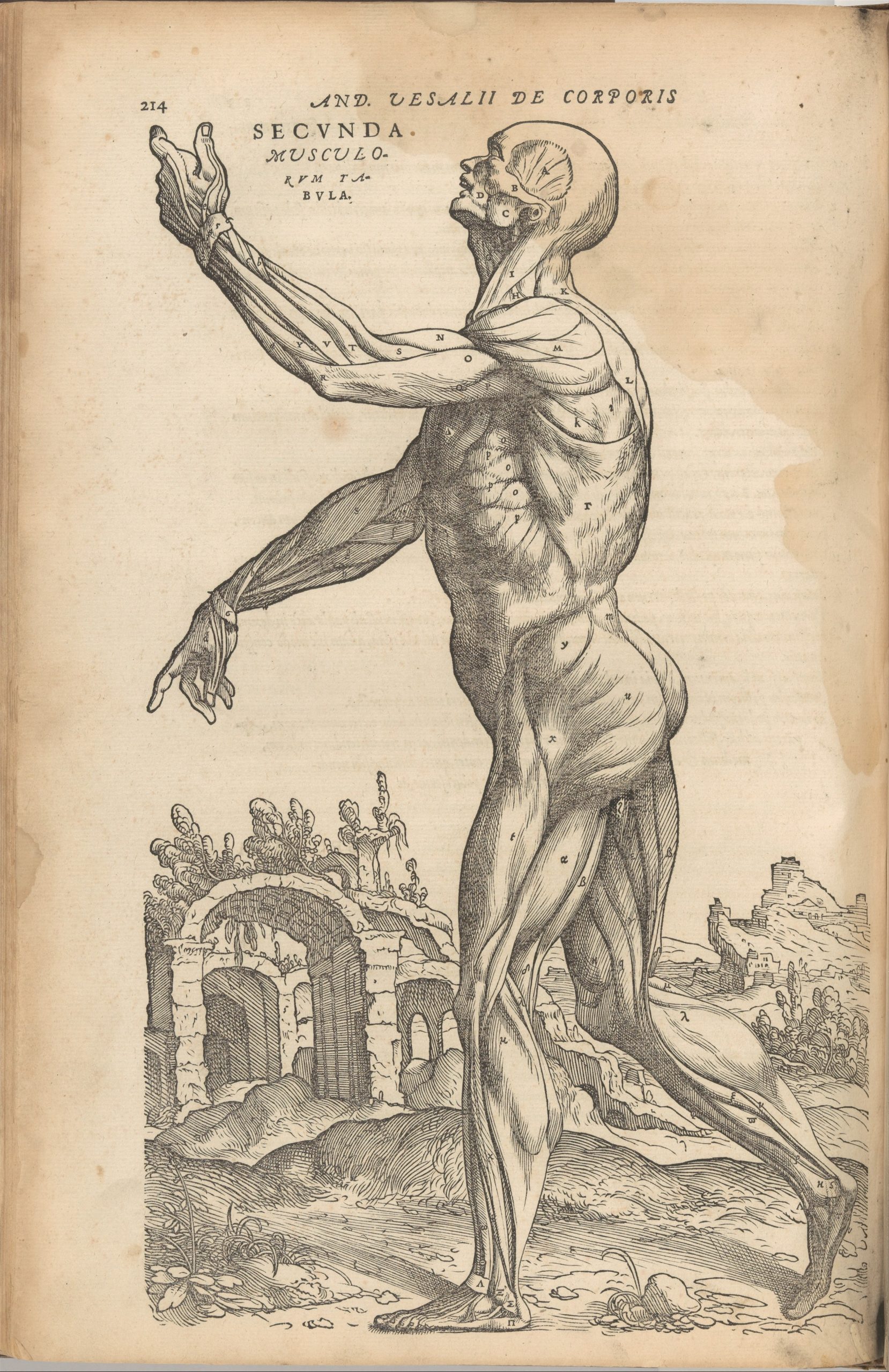

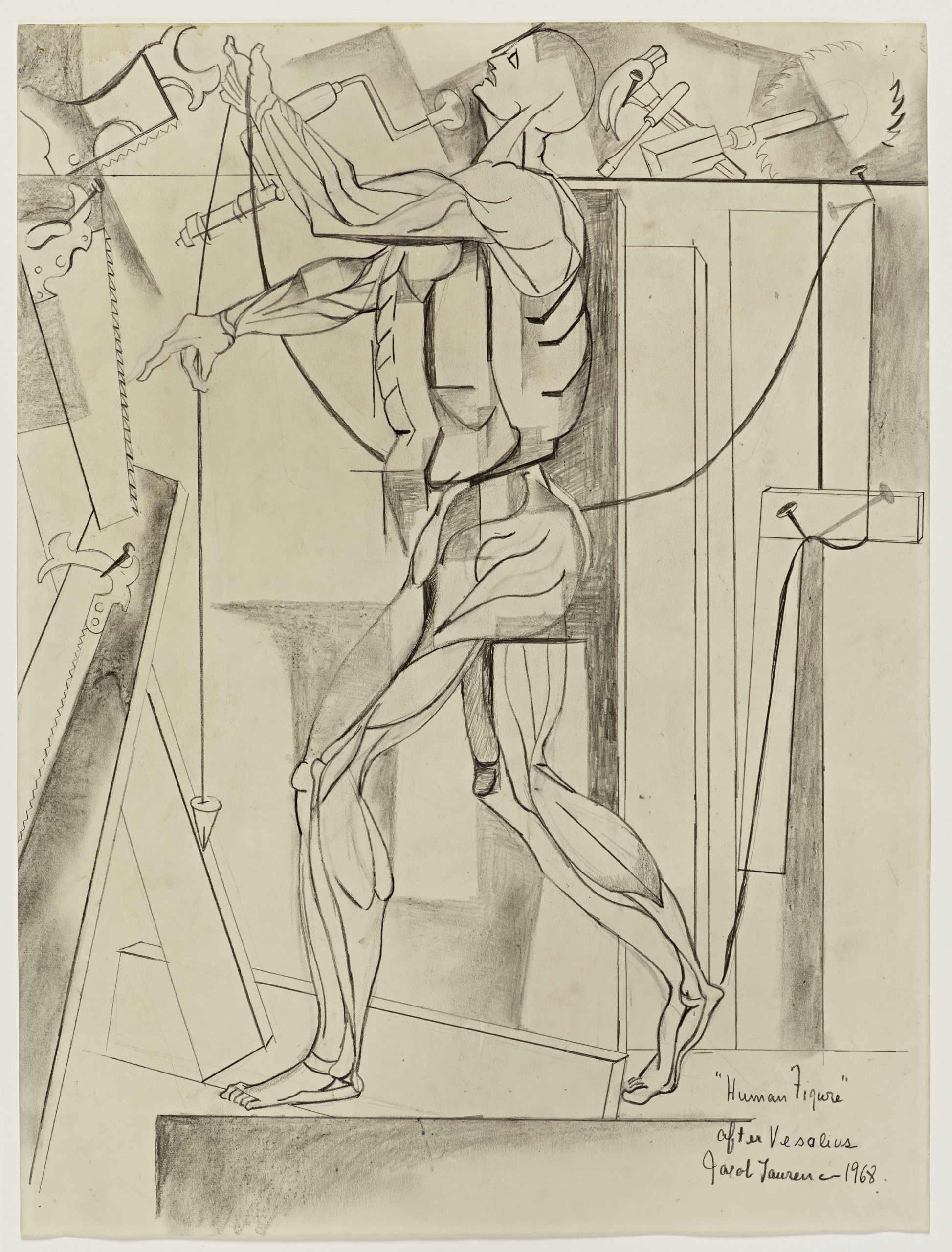

Leaning against the wall to Lawrence’s left is a figure study that mirrors the artist’s pose—in fact, they’re both mimicking a third body, a famous anatomical illustration from the Renaissance (fig. 2) that Lawrence drew repeatedly from 1968 to 1996 (fig. 3).[1] The triple reference poses a sly challenge to the viewer: where do you look for the artist’s presence in his art? Where does his work fit into the broader arc of art history?

With the painting enlarged behind him, Lawrence, nearing the end of his first decade as Professor of Art in the School of Art + Art History + Design, began his address to the crowd. Hundreds of his fellow University of Washington students, faculty, staff, and community members had gathered in Kane Hall to hear the renowned artist deliver the third annual distinguished faculty lecture, a recognition reserved for an internationally acclaimed scholar whose work had demonstrably impacted their profession, the work of others in their field, and society at large. Lawrence certainly fit the bill. By 1978, he’d held a central position in the American art world for nearly 40 years, a long and prolific career that the Whitney Museum of American Art had just honored with a major retrospective exhibition (a mark of prestige that the evening’s MC compared to winning an Oscar—he wasn’t wrong).

Lawrence could have easily started his lecture at his career’s beginning, perhaps with a panel from his monumental Migration Series of 1940-1941, undoubtedly his most famous project. Instead, he started in medias res, in the middle of things. “I thought I would start with the latest slide so you can see where I am in this moment,” he said, reminding the audience that his work was far from finished. Of course, he was right: he continued to make art for the next two decades until his death in 2000 at age 82, much of it just as complex and incisive as The Studio. And yet for many scholars and critics, it’s as if Lawrence’s artistic trajectory came to a hard stop when he and his wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight, left New York City permanently for Seattle in 1971. Nearly 30 years of his career wedge into a few lines in a closing paragraph, or a page in an epilogue. Art historian Patricia Hills captured the dominant attitude succinctly in the epilogue of her 2009 monograph Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence. “Lawrence’s works in Seattle, with the exception of the powerful Hiroshima series, lost some of their edge,” writes Hills, chalking the dulling up to a “subduing of color” inspired by the constant Pacific Northwest drizzle.[1]

The essays in this volume, researched and written by the participants in the Spring 2021 art history seminar “Art and Seattle: Jacob Lawrence” at the University of Washington School of Art + Art History + Design, challenge the prevailing perspective that the “complete Jacob Lawrence” is a story that begins and ends in New York City. In so doing, we take our lead from the artist’s own framing of the Seattle period as a critical stage in his artistic development, in which conceptual and formal concerns explored across his long career converged and became more of the sum of their parts. Some of these insights are drawn from the recording of Lawrence’s previously unpublished 1978 distinguished faculty lecture, discovered by our colleague Morgan Bell midway through the term, and made available to the public for the first time as part of this project. In the lecture, The Studio is merely the first stop on a winding, non-linear, and cumulatively building account of Lawrence’s artistic philosophy. Forking paths begin to come back together as the artist nears the talk’s conclusion:

I consider it a strand, all of these things running through my life. I don’t separate them. I don’t separate my series on Toussaint L’Ouverture where I become the rider, because I’m searching for an identity. I don’t separate my life when I do a series of paintings on the Migration, because that is a part of my life although I did not participate in that. I do not separate these things when I do a work on Harriet Tubman. I cannot separate it because it’s a part of me, a part of my life, a part of my experience. And this is what makes me. This is it, this is the experience, this is the search which continues on and on for that elusive thing. I go back to this because it is tied up with the picture plane. I deal with the picture plane for there’s always the search involved in that. What am I looking for? I don’t know. I have no idea. There’s a certain magic there, I go back to Albers’ words. A certain gestalt that I’m looking for. I don’t know if I’ll ever find that.

Here, Lawrence sets the record straight: his late work is not a dulling, but a sharpening. But seeing how the Seattle works contain and continue to hone the edge of his earlier years requires viewing the period from a fresh perspective. The Studio coaxes us to do precisely that. “You can see where I am in this moment,” the artist said of this painting, a self portrait in two places—or times—at once. Out the window of his 1977 Seattle studio is a 1943 Harlem street.

About Jacob Lawrence in Seattle

Art history’s job is to show how an artwork, or an artist, fits into a larger and more complex social, intellectual, or cultural frame. It’s a lot like putting together a puzzle. Through research, we locate all of the puzzle pieces: individual artworks, people, life events. Through interpretation and analysis, we show how they all interlock to form a bigger picture. Scholars have been steadily assembling the Jacob Lawrence puzzle for more than half a century, but the pieces from the Seattle period are still loose and unintegrated, rendering the big picture incomplete. The goal of our Spring 2021 seminar was to begin filling in the missing pieces; to gain a deeper and more thorough understanding of Lawrence’s art historical significance, both before and after 1971. Over ten weeks, we intensively studied his prolific and complex body of work, analyzing it both on its own terms and in relation to a variety of art historical contexts. We read hundreds of pages of critical and scholarly writing, tracing the patterns and shifts in interpretation from the beginning of his career in 1940 to the present. We pored over letters, contracts, news clippings, and interview transcripts in the archives to find the details left out of existing narratives. This book, Jacob Lawrence in Seattle, is the result. Each student in the seminar spent the quarter researching and developing an essay anchored in a single artwork that Lawrence created during his time in the Pacific Northwest. Their essays situate single paintings like 1977’s University or contained series like the Hiroshima illustrations of 1983 within wider contexts or thematic frameworks, ultimately considering each anchor artwork as a loose piece in the still-unfinished Lawrence puzzle.

So where do the Seattle pieces fit in that picture? The essays in this volume concentrate on integrating Lawrence’s post-1971 artistic production into existing art historical conversations: questions of modernism and abstraction, art and politics, materiality, self-portraiture, and so forth. Of course, like the quarter-long class itself, this scope is necessarily and intentionally quite limited. However, as our discussions frequently explored, looking closely at Lawrence’s time in Seattle from 1971 onwards can illuminate far more than art historical through-lines or expanded definitions of modern painting. In this foreword, we want to briefly address what the essays leave (for now) unwritten.

Art and Seattle: Jacob Lawrence is the first class at the UW to center on the work of the School of Art + Art History + Design’s most distinguished former faculty member. It was motivated, in large part, by a desire to learn more about Lawrence’s legacy at the institution where we work and study, in the region where we live, and within a community where his profound impact is visible in so many ways. Visible is the operative word: in 2021, exactly 50 years after accepting a permanent position at the UW, Jacob Lawrence is once again in the spotlight. A major exhibition, Jacob Lawrence: the American Struggle, toured museums across the U.S. from 2020-2021, with a wildly popular sold-out stop at the Seattle Art Museum. The Struggle show made headlines throughout its tour, including widely shared stories announcing the surprise discovery of two panels long thought to be lost (“lightning strikes twice,” the New York Times proclaimed). While the Struggle panels were on view at SAM, the University of Washington made its own big announcement about the artist. The Jacob Lawrence Gallery, named in honor of Lawrence, will be completely remodeled and expanded in the next two years as part of a multi-million dollar initiative devoted to elevating the arts at the UW. Positioning the Gallery at the center of this transformative campaign is significant: it marks a growing recognition, beyond the immediate arts community, of the vital importance of programs like the Jacob Lawrence Legacy Residency, the Black Embodiments Studio, and its annual BIPOC graduate curatorial fellowship to the larger mission of the 21st-century University.

Given these exciting developments, Lawrence’s name, art, and face have recently appeared everywhere. Through social media posts, fundraising campaigns, and larger-than-life museum banners, more people than ever before are seeing and learning about Jacob Lawrence and his art. But with some exceptions, these formats can rarely deliver more than a few sentences of text or a minute or two of audio, and in turn can only scratch the surface of the artist’s longer story—let alone the deeper art historical significance of his work. As participants in a seminar all about digging into that deeper historical material, we recognized the benefits of raising basic awareness about the artist, but were also acutely aware of how much more there was to say. In the necessary brevity of an instagram post, the core message risks shifting away from the artist and towards the institution’s own image and desire to communicate its progressive values. On the other hand, a deeply-researched historical account doesn’t do much good if it’s only accessible to people with a university library affiliation and a fondness for academic jargon. We wondered: what would a middle ground between social media and scholarship look like?

Examining how, and in what level of detail, we tell Lawrence’s story is more than just a rhetorical exercise. His arrival at the University of Washington coincided with a period of unprecedented reckoning with issues of structural racism and exclusion on this campus and in universities nationwide. Across the country, students and activists demanded change, including but not limited to the hiring of more faculty of color. And across the country, university administrations tried to communicate, loud and clear, that they were listening and changing. One common strategy involved putting individual faculty members like Lawrence in the spotlight as evidence of an institutional commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. In her exploration of diversity work in higher education, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, feminist scholar Sara Ahmed explores what it means for institutions to deploy “diversity as a form of public relations.”[2] Citing the idea that “diversity” has become synonymous with “people who look different,” she recounts an instance in which an organization wanted to photograph the diversity committee that she was serving on to share on behalf of the larger organization:

When our team was their picture, it created the impression that the organization was diverse. Arguably this was a false impression: the other teams were predominantly white. On the other hand, when our team was pictured, it helped expose the whiteness of the other teams. Even if diversity can conceal whiteness by providing an organization with color, it can also expose whiteness by demonstrating the necessity of this act of provision.[3]

For Ahmed, diversity-as-PR is one of many ways that the bodies of people of color are literally used to “repicture” the institution that employs them. “People of color are asked to concede to the recession of racism: we are asked to ‘give way’ by letting it ‘go back,” she writes. “Not only that: more than that. We are asked to embody a commitment to diversity. We are asked to smile in their brochures.”[4] The ultimate effect is at once an upholding of institutional whiteness as the norm through the devaluing of faculty, staff, and students of color. People are reduced to instruments, or as Ahmed writes, “bodies of color provide organizations with tools…we become the tools in their kit. We are ticks in the boxes.”[5]

The photo request in Ahmed’s example occurred in the 2000s, but it would not have been out of place in 1968, when the University of Washington began laying the groundwork for Jacob Lawrence’s hire. In a Board of Deans meeting that spring, held amidst ongoing student unrest about the overwhelming whiteness of the university, participants discussed how Black professors could be made “visible without having them feel as if they are being used.”[6] It’s not for us to say whether Lawrence felt he was being used, or what he felt at all. But after permanently joining the University of Washington faculty in 1971, he was certainly made visible. The 1978 Distinguished Faculty Lecture cited throughout this volume was not the only time Lawrence was on stage: he actively participated in University-wide efforts to recruit and support Black students and faculty, and around diversity and recruitment issues in general (Fig. 4).

The parallels in diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts between 1971 and 2021, between Lawrence’s time and ours, raises a question: what progress has actually been made? And what still hasn’t changed? The makeup of our class is a glaring example of the ways in which diversity efforts often result in reproducing the existing structures of institutional whiteness. Art and Seattle: Jacob Lawrence was taught by me, a white professor. No Black students were enrolled in the course. To overlook this reality is to acquiesce to whiteness as the unnamed default–in art history, in academia, in higher education, and beyond. At the same time, attempting to hurriedly “conceal whiteness by providing [our] organization with color,” as Ahmed put it, is damaging in a different way. We have opted, instead, to call attention to the subjectivities represented and not represented in our seminar. To disrupt the ongoing reproduction of institutional whiteness, what must change now?[7]

Acknowledging that we, the authors of this volume, are implicated in replicating the structural whiteness of the institution is not enough on its own: it must also involve interrogating how those same power structures can enter into our work as art historians. Reflecting on our own subject positions as non-Black authors writing about work by a Black artist was a first critical step. Close reading of essays by art historians including James Smalls and Richard J. Powell, and artist Simone Leigh’s 2019 explanation of how she defines the audience for her work, guided this conversation.[8] Reading their scholarship and statements pushed us to carefully consider the methodological frameworks we brought to this project, and to clarify the nuanced but significant differences between writing about the artist or art through a subjective framework, and writing about the art through an art historical lens. In an effort to practice the latter approach, our essays draw heavily on archival documents, particularly Lawrence’s own statements, and are anchored whenever possible in the scholarship of Black authors, scholars, and writers. We are immensely grateful to Professor Luther Adams for the feedback and suggestions he provided on this topic, in addition to sharing his expertise on Lawrence and the historical context of migration.

Finally, we continue to grapple with the question of how to engage with Lawrence’s legacy in a way that does not reduce his complex body of work and lived experience to public relations data. The public-facing aspect of Jacob Lawrence in Seattle is our attempt to counterbalance and complement decontextualized invocations of his name and art. This volume is grounded in our belief that renewed interest in Jacob Lawrence must go hand in hand with sustained and historically accurate attention to his artwork and its place within art history. In turn, that information must be as widely and freely available as a social media post. As students and scholars embedded within the institution, we hope to use our power and privilege to share what we have learned.

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence, 2009, 260. ↵

- Sara Ahmed, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham ; London: Duke University Press, 2012), 34. ↵

- Ahmed, 33. ↵

- Ahmed, 163. ↵

- Ahmed, 153. ↵

- “Board of Deans Meeting Minutes,” April 3, 1968, University of Washington Office of the President Records, Box 28, University of Washington Special Collections. ↵

- Ahmed, On Being Included, 34. ↵

- James Smalls, “A GHOST OF A CHANCE: Invisibility and Elision in African American Art Historical Practice,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 13, no. 1 (1994): 3–8; Richard J. Powell, “Linguists, Poets, and ‘Others’ on African American Art,” American Art 17, no. 1 (April 1, 2003): 16–19; “Simone Leigh on Instagram: ‘I’ve Seen Some Preliminary Thoughts on the Biennial and Concerns about Radicality. I Need to Say That If You Haven’t Read, Not a Single…,’” accessed June 22, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/BxiJI58gl4t/?hl=en. ↵