15 Sunday School

Lessons on Creation from Jacob Lawrence

Nicolas Staley

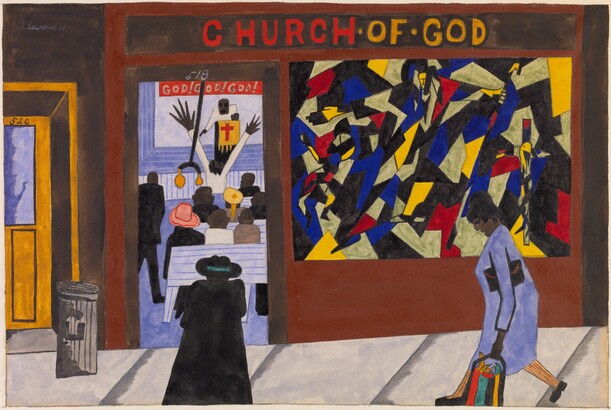

A young man steps off the train. It is 1942, and he is tired. The journey was long, and even now it is incomplete. His family is with him, and they are tired too. They have few belongings, but they have an abundance of hope. The man and his family walk down the street. Everyone they see is black, like them. Sounds of a man yelling waft through an open door. The family stops, stares, and listens. The yelling man is a minister, and his yelling is a sermon. Hovering above them on the building’s marquee are the words “Church • Of • God.” This is Harlem. The minister sees the young family and ushers them in. The anxieties of travel are relieved. They listen as the minister speaks of community, class, and color. Most of the people are very poor. Rent is high. Food is high. The family stays for the sermon and leaves with renewed vigor. They walk down the street searching for their house. In Harlem, They live in old and dirty tenement houses. The family tells themselves that it is better than where they came from. They cannot find their building, but they see another church. Another man is yelling- it is another sermon. The family continues to pass churches in search of their home. There are many churches in Harlem. The people are very religious. They finally arrive, and while their journey is complete, their struggles are not. This is a family living in Harlem.

This is not a story of one family, but many. Hundreds, thousands, millions even. The family has fled the South, which held nothing for them. The North is somehow better, and they get to work improving their community. It is difficult, and even though they have fled Jim Crow, he seems to have followed them in a new form. This is Harlem: a black community constantly growing, fed by the Great Migration.[1]

This is Harlem. Most of the people are very poor. Rent is high. Food is high. They live in old and dirty tenement houses. There are many churches in Harlem. The people are very religious. This is a family living in Harlem. These crisp phrases title the individual panels of Jacob Lawrence’s Harlem series, which he painted between 1942 and 1943 (fig. 1).[2] The series documents the living conditions in the Harlem neighborhood where Lawrence was raised, which are sometimes good, but mostly bad. One work stands out amongst the others in the Harlem series because it hides more than it shows. As its caption declares, people in Harlem were very religious, and through religion, they found the means to not only survive but thrive. This is not a story of one family, or hundreds, or thousands, or millions even. This is a story about religion, told by Jacob Lawrence in interconnected chapters across his long career, and he is about to take us to Sunday School.

Creating Genesis

This essay focuses closely on one chapter of Lawrence’s narrative of religion and survival: The Eight Studies for The Book of Genesis (hereafter: the Genesis series), which he created for the Limited Editions Club (LEC) of New York (figs. 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11). The LEC aimed to create high-quality reproductions of classic literature. The Genesis series was not the first time that Lawrence had worked with the LEC; some years earlier in 1983, he provided the firm with eight paintings to illustrate John Hersey’s Hiroshima. The eight works of 1989-1990 encompass Genesis 1, detailing the creation of the world and its living inhabitants. Printed in two separate editions, the eight works were also included in the LEC publication of the King James Version of the book of Genesis. Lawrence signed and numbered each book, of which 400 were made.[3] The Genesis works remain relatively ignored within Lawrence’s oeuvre and thus provide a fresh opportunity to consider how, and to what extent, the artist’s personal life, upbringing, and the community of Harlem shaped his art. Lawrence’s Genesis series eschews the link between the crucified Christ and the motif of the lynched black man, instead refocusing the narrative to center on a Black God and his congregation. By intertwining the story of Genesis with that of the Great Migration, Lawrence empowers black Christians with the abilities of creation and enhancement. As God and his congregation create a world, so too do black Christians use religion as a tool to shape and form their communities in an era of mass migration and societal upheaval.

This analysis works to synthesize multiple histories that have yet to enter the collective conversation around Lawrence’s art. These histories have provided invaluable knowledge and support to this paper, and as such, this essay is indebted to the phenomenal work of scholars of African American history and art. Scholars such as Kymberly Pinder, Phoebe Wolfskill, Kristin Schwain, Amy Hamlin, and many others have provided exceptional research into the life and art of Jacob Lawrence and his contemporaries.

Embracing a Tradition

While the original eight works for the Genesis series were paintings, their status as prints is inextricably tied to their content and message. Printmaking was, and remains, popular among black artists; the widespread distribution and accessibility allowed for communities with little means to create easily distributable works of art.[4] Lawrence’s personal history as a printmaker began in 1963 with his first published print and continued until his death in 2000.[5] Romare Bearden, a contemporary and close friend of Lawrence, was highly invested in printmaking as both a tool to create works of art and to enrich African American communities.[6] Given Lawrence’s personal relationship with Bearden, who went on to found the art collective “Spiral”, he was no stranger to the power of printmaking as a tool for enlightenment and equality.[7] His early-career chronicles of American history are echoed in the use of prints after 1963, as the medium itself became a staple within the art of black communities, he can be seen as further honoring this tradition. The democratization of printmaking reflected the environment of Lawrence’s youth, with arts programs and workshops in Harlem. With the overall goal of teaching creative and marketable skills to the youth of Harlem, printmaking can be seen as the evolution of these ideas. Therefore, putting aside the content of the Genesis series, their material quality alone speaks to a legacy of communal betterment through art. The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, founded shortly before Lawrence’s death in 2000, represents the continuation of these principles that helped shape both Jacob and his wife Gwendolyn, also an artist, throughout their early careers.

The Black Man of Sorrows

On August 31st, 1924, in Liberty Hall, New York, the “Fourth International Convention of Negroes of the World” concluded with a statement that corrected the “mistake of centuries” and ushered in a new era in African American Christianity: Jesus was a black man.[8] Some six thousand people gathered to hear a sermon by Sir George A. McGuire, Lord Primate of the African Orthodox Church.[9] The event concluded with the statement that Jesus was a “Black Man of Sorrows”, and the Virgin Mary was “canonized as a Black Madonna.”[10] These declarations extended from the same robust discussion about racial cooperation and self-determination that defined the Harlem Renaissance period from 1918 to the mid-1930s.[11] During this period, religion was frequently invoked as a balm for the injustices suffered during the ongoing fight for equality. The pain of this life was in service of salvation in the next, and the racial violence and inequality of America strengthened this faith.[12] Christ’s own agony at the hands of his captors was seen as allegorical to the pain felt by black Christian communities throughout America. The endurance of such hardships within this life mirrored that of Christ, and his sorrows came to represent those of racial violence and systemic racism.[13]

Crucifixion and lynching, two extreme acts of violence with powerful parallels, came to embody the struggle of black Christianity as a whole. The lynched black body became a symbol of martyrdom akin to that of the crucified Christ; these symbols served as concrete links between the religiosity of black communities and their struggle under an oppressive system.[14] Just as Christ’s death was a pathway to salvation, so too was continual faith in the face of violent racism. During the same event in which Christ was deified as a Black Man of Sorrows, activist Marcus Garvey argued that it was imperative for black Christians to see God in “his own image and likeness” akin to Germans and Anglo-Saxons.[15]

It was against this historical backdrop that Lawrence painted a black crucified Christ in Catholic New Orleans, and in doing so aided in the continued elevation of this parallel (fig. 5). Within this work, a black woman approaches a collection of religious items. A number of crucifixes are strewn throughout the painting, but the one in the center carries a black body. The Christ on this cross is a black man, and next to him is a painting of the Virgin Mary, who is also black. The Virgin looks down at her crucified son, as many mothers had to look at their lynched sons. Both Christ and the black woman are given no features or defining characteristics, Lawrence rendered them as a stand-in for the black communities of America. Black Christians saw themselves reflected in Christ, and their battles were his battles, strength in faith mirrored strength in life.

Migrants and Ministers

Lawrence’s propensity to create sociopolitical art brings his own religion into question when examining the Genesis series. Although quite reserved, Lawrence did speak about his own religious upbringing and its effect on him while creating these pieces:

“I was baptized in the Abyssinian Baptist Church [in Harlem] in about 1932. There I attended church, I attended Sunday School, and I remember the ministers giving very passionate sermons pertaining to the Creation. This was over fifty years ago, and you know, these things stay with you even though you don’t realize what an impact these experiences are making on you at the time. As I was doing the series I think that this was in the back of my mind, hearing this minister talk about these things.”[16]

The Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem is located on West 138th Street in Harlem and is still a central part of Harlem’s community today. Liberty Hall, where Jesus was deified as a Black Man of Sorrows in 1924, was also located on West 138th Street only a few doors down from the church. The legacy of the 1924 sermon, and Garvey’s speech, would undoubtedly be on the minds of those within the Harlem community around the time Lawrence was baptized. It was within this environment that Lawrence first embraced religion, and the lasting impact of this black Christian discourse can be seen nearly sixty years later within the Genesis series. The pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church during Lawrence’s youth was Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Sr., who taught a message of “applied Christianity” that translated biblical teachings into public outreach.[17] The passion with which Rev. Powell Sr. went about his sermons was akin to the theatrics of pastors such as Junius C. Austin, who would begin each sermon at the Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago by emerging from a painted tomb, greeted by angels.[18] Rev. Austin’s symbolic resurrection day in and day out was paralleled in his social reformist sermons, further strengthening the link between black activism and black Christianity.[19]

Men like Reverends Austin and Powell Sr. emerged as pillars within their communities, both spiritually and politically. The role of ministers within black Christian communities was central to instituting social and political reform and cemented the Black Church as an engine of societal change.[20] By 1937 the Abyssinian Baptist Church had grown to become one of the most powerful Protestant churches in the nation, boasting seven thousand members. Rev. Powell Sr. used this political capital to aid in the urbanization and migration of rural, Southern, and often impoverished, black Americans during the Great Migration.[21] Lawrence’s Genesis series features an analog of Rev. Powell Sr. and thus offers insight into the artist’s use of anecdotal personal experience in illustrating a universal message.

Exploring Genesis

Lawrence’s Genesis series takes black Christian ideals of salvation through faith and suffering and reworks them as ideals of black power and black liberation through religion. The parallels between Lawrence’s own Christian upbringing and the Genesis series are starkly apparent, and it is here that Lawrence’s commentary shines through. Throughout the series, God is rendered as a black man, but where the black Christianity of Lawrence’s youth equates the black body to that of a crucified Jesus through a shared form of suffering, Lawrence empowers the black body by linking it with divine power. God is not a black man beaten by an oppressive system, but an all-powerful being capable of creating life. His congregation looks on in awe as God fills the world. Through this imagery, Lawrence comments on the power of faith within the Harlem community, and its ability to shape and create. The black God is shaping a world for his black congregation, and they in turn use the teachings of God to enrich their community. Through the narrative cycle of the Genesis series, Lawrence reinforces the positive, life-changing, community building, powers of religion.

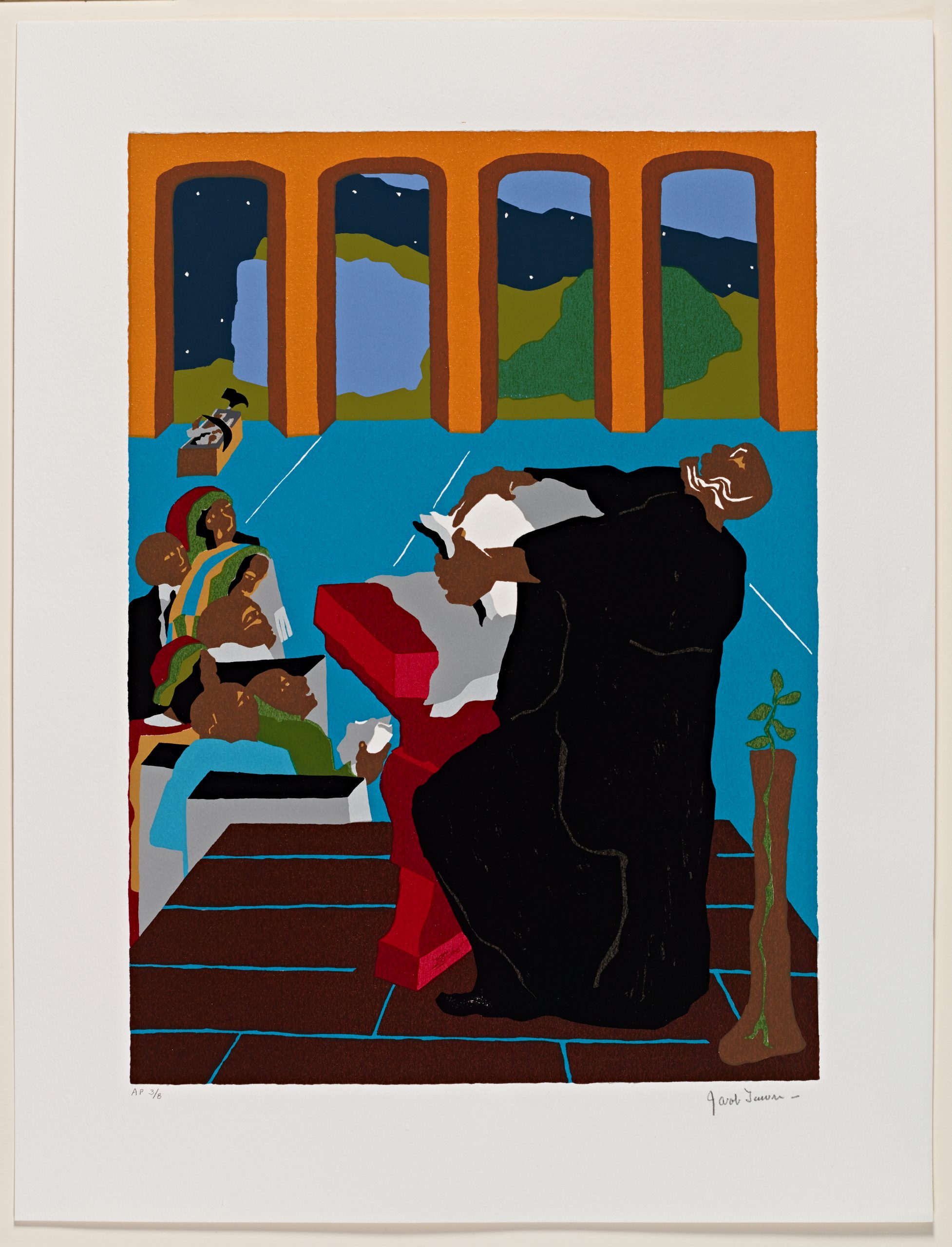

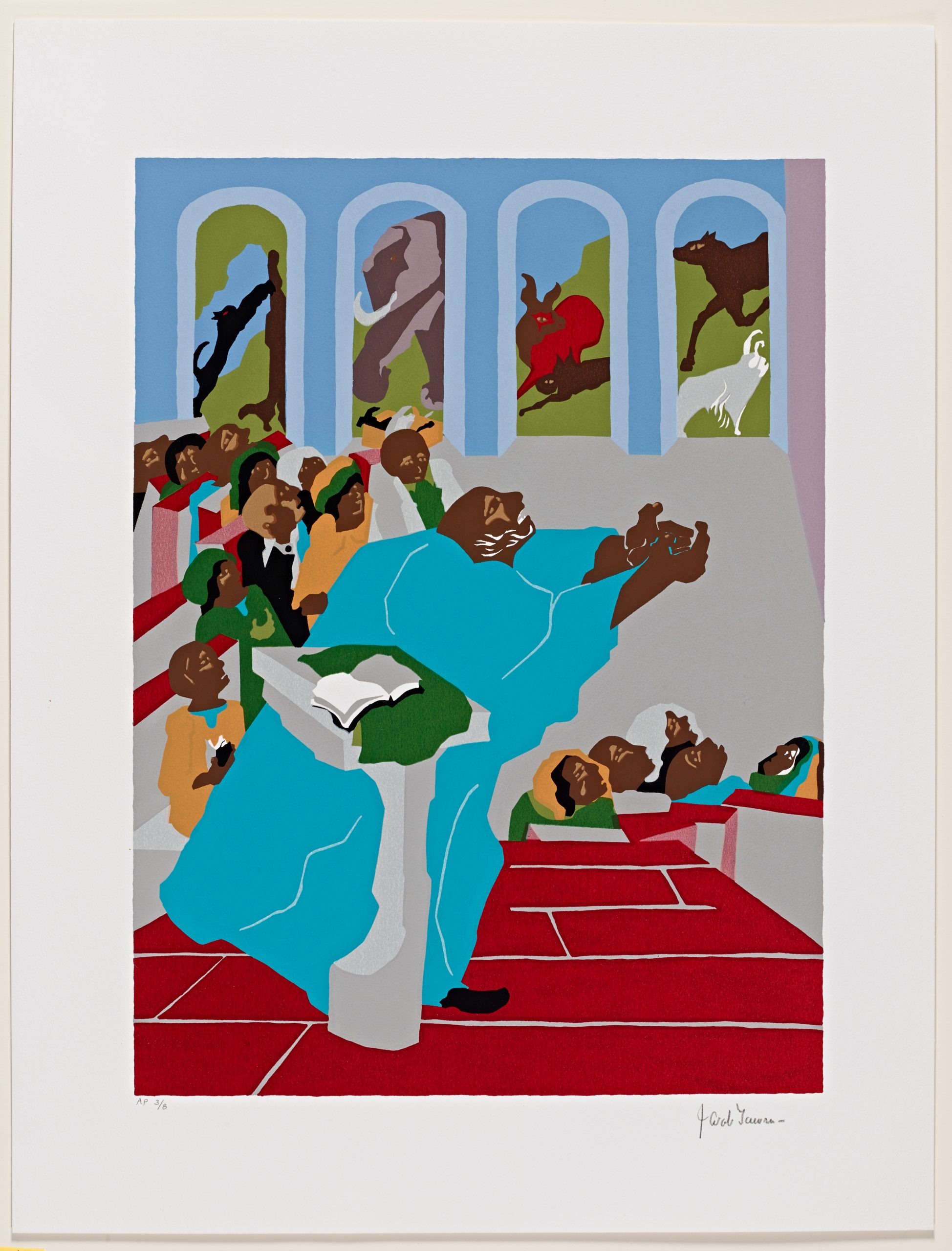

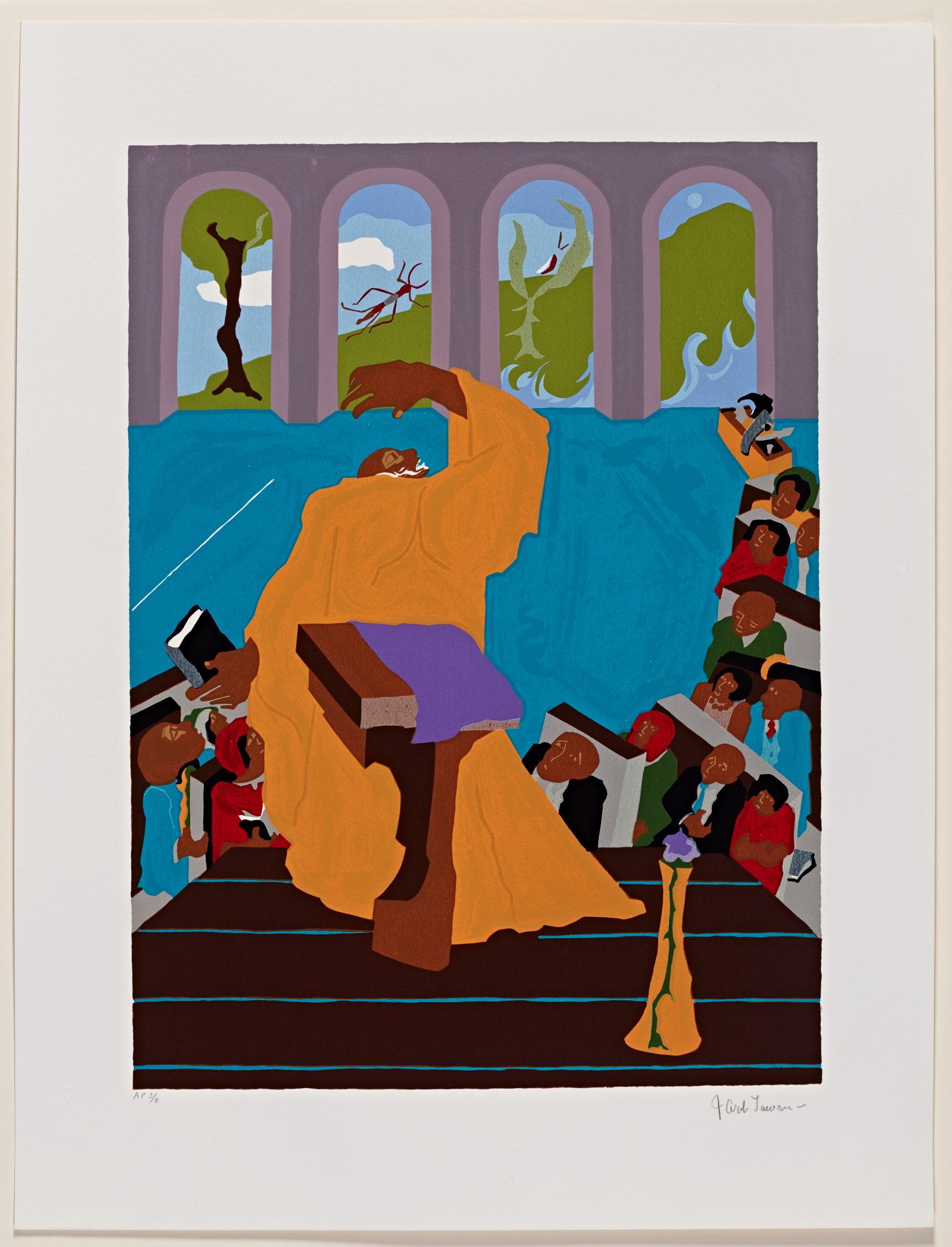

Genesis No.1 “In the beginning all was void.” commences the Genesis series with its cloying black void peering through the arcades of God’s church (fig. 6). The congregation itself huddles together in a state of fear and anxiety. The woman closest to God sheds a single tear of anguish. God himself is down on one knee, with head tilted skyward, and arms outstretched in a plea of desperation. He encourages his congregation to create a world for him to populate.[22] A toolbox is placed near the congregation, its inclusion paramount to Lawrence’s narrative: God has provided the tools for his congregation to create the world in which they live. Lawrence’s fondness for tools- in his words, “the perfect symbol,”- is well documented.[23] The famous Builders series, examined earlier within this book, focuses heavily on tools within many different contexts and environments. The tools, bible, God, the church, and the congregation remain present throughout the entire series. A large vase with a single flower is also present in all but one of the works. Above God’s head is the bible which is given a covered lectern to rest upon and never far from him, as the bible itself is central to Lawrence’s story of Genesis. Furthermore, the inclusion of printed materials within these works provides metacommentary on the importance of printed materials within black communities, and on the role of the Genesis series itself as printed artwork.

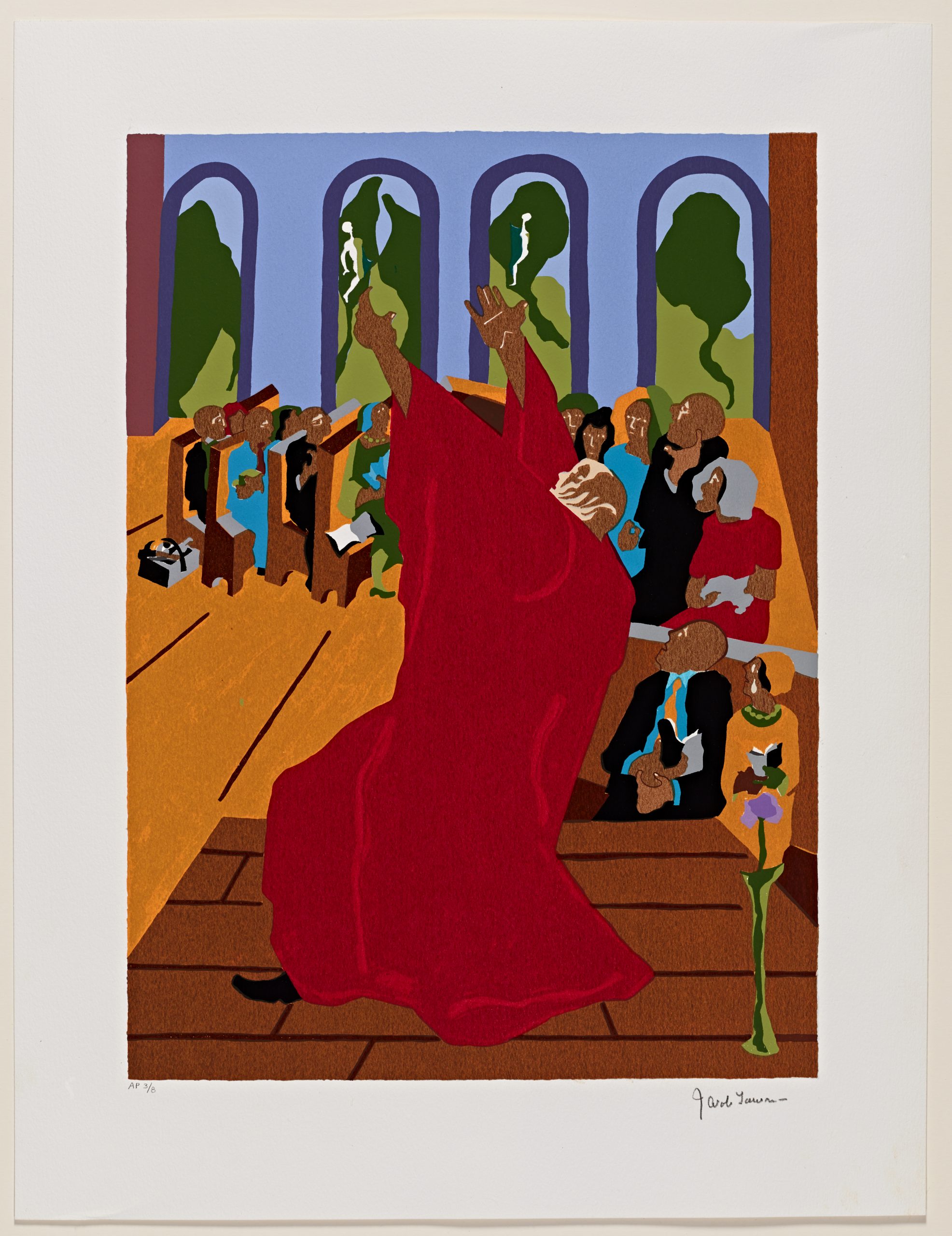

Genesis No.2 “And God brought forth the firmament and the waters.” sees all the familiar components of No. 1 shifted, transformed, and animated (fig. 7). A blue robe becomes gold, an orange floor becomes gray, brown tile becomes red, the white toolbox becomes yellow. These changes avoid repetition by creating a sense of energy and movement throughout the works, as well as spotlight progress within the congregation as they work in collaboration with God to continually reshape their environment. The bible is in the hands of a congregation member and the tools have moved back towards the arcades, as they are no longer in use. The congregation has created the world, it is now God’s turn to fill it. Through the continued changes within the series, Lawrence highlights the symbiotic relationship between the black community and the church, both of them changing together for the betterment of their environment. The congregation must build a community for God to improve, akin to Harlem providing a community with which Rev. Powell Sr. could enact social justice and public outreach. It is through this narrative that Lawrence simultaneously acknowledges and eschews the tradition of the black lynched Christ in favor of the powerful black God and his thriving community. He assigns the role of creator to common black Americans, allowing “the minister [to form] the foundation on which his congregation builds community.”[24]

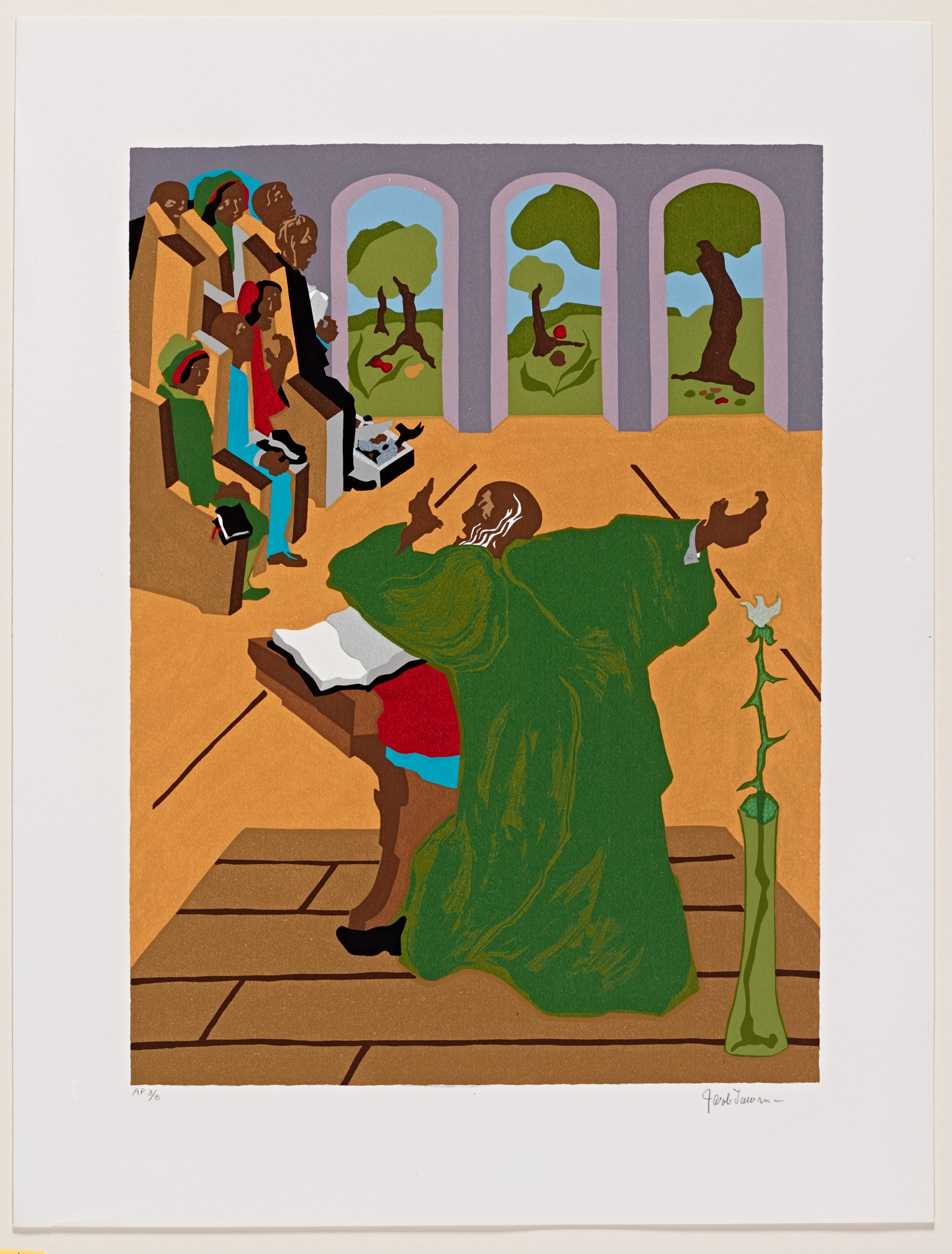

Genesis No. 3 ‘And God said, “Let the earth bring forth the grass, trees, fruits and herbs.” continues the pattern of movement and alteration found within the previous work (fig. 8). The colors change, the congregation moves, as do their tools. The bible is back on God’s lectern, and the flower within the vase has shifted from lavender to light green. Genesis No. 4-8 all continue with Lawrence’s established rhythm. The pieces of the story move about and evolve, but the essential meaning remains the same. As art historian Kymberly Pinder argues, the kinetic energy present throughout the works speaks to a tradition of bodily participation within black Christianity. The ability to move about uninhibited “epitomizes [a] kind of freedom” inherited from West African religions and cultures.[25] The bodily agency that is afforded to God and his congregation serves to break the bonds of servitude that regulated the black body during slavery. The crucified Christ and the Lynched Black Man cannot move of their own accord, but God and his congregation have that freedom.

Disrupting the Canon

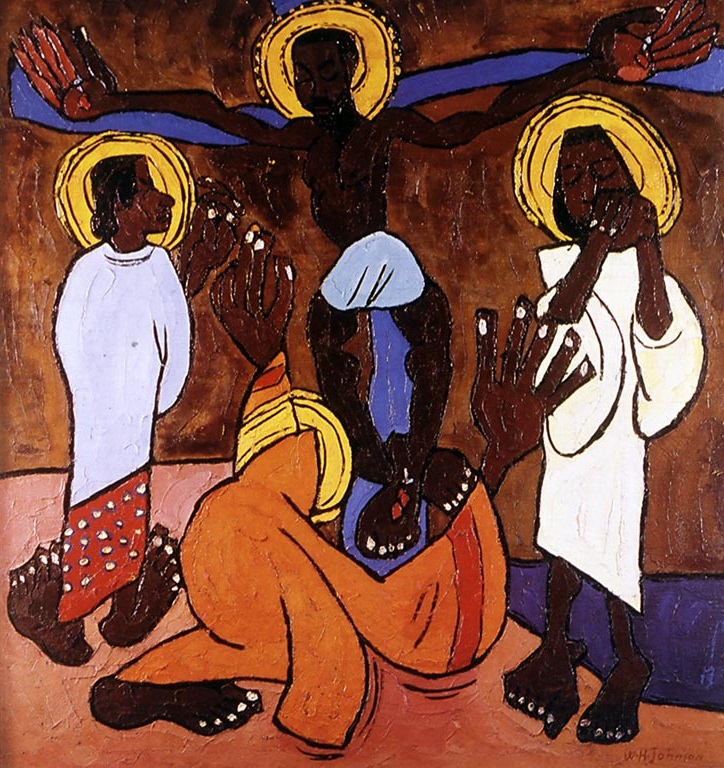

William Henry Johnson’s 1939 piece Jesus and the Three Marys embodies the canon which Lawrence’s Genesis series ultimately transforms (fig. 9). Stylistically, Lawrence’s Genesis series is not dissimilar to Johnson’s work. Both feature relatively flat characters with exaggerated features and oversized extremities. The coloration is uniform, with little modulation to account for changes in light or depth. This is where the similarities end, however. Johnson’s work embraces the traditional imagery of the crucified Christ, clearly referencing the lynched black man. This reference was commonplace among black artists in the 1930s and was explored again by Johnson in Lynch Mob Victim, also from 1939. Both of Johnson’s works feature a black victim surrounded by three black women, echoing the crucifixion these men have been “unjustly accused” and killed by a “prejudiced and unenlightened mob.”[26] Some of Johnson’s works were featured in the 1935 Antilynching Exhibition curated by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[27] While Lawrence references the pictorial tradition but ultimately alters it, Johnson’s works reinforce and advance the link between lynching and crucifixion. The symbolism and expressionist forms, which favor emotional clarity rather than physical harmony, within Johnson’s Jesus and the Three Marys serve to produce an “aesthetics of transcendence,” disregarding formal pictorial language to radiate an “internal felt expression of Christianity.”[28] Similarly, Lawrence’s own forms and symbols transcend their semiotic structure. A black minister assumes the role of a black God, and this black God represents religion as a concept. The community of Harlem serves as a congregation that becomes responsible for building their own world. Simple tools are transformed into instruments of divine creation which serve to reshape political and societal barriers.

Implementing Heritage

Panel six of Genesis, “And God created all the beasts of the earth.” stands out from the rest of the series. God is seen with arms outstretched and head tilted towards the heavens. In the arcades of the church a panther, an elephant, and an antelope can be seen, all three of which are native to the African continent. Instantly a connection is made between African American ancestral heritage and black Christianity. Akin to the kinetic forms of God and his congregation, whose movement is West African inspired, so too are the animals chosen by Lawrence a reminder of collective black heritage. By deepening these connections within the work, Lawrence continues to reinforce the ideals of a black community made for, and by, black Christians. To illustrate each passage of Genesis, Lawrence evokes black protestant tradition by linking a specific biblical passage to its visual representation. Essentially, Lawrence presents what art historian Kristin Schwain describes as a “living document that creates community and shapes the lives of those who read, preach, and hear it.”[29] Unlike the other works within the series, Genesis No.6 does not feature a flower and vase. The outline of these objects can be seen within the lower right corner, but it seems Lawrence painted over them later. Furthermore, this work changes the composition of the congregation by having the churchgoers on either side of God. This choice will continue until the end of the series, with the congregation getting noticeably larger as the panels progress.

Genesis No. 8 “And creation was done-and all was well.” provides a fulfilling conclusion to the series (fig. 8). God appears for a final time with an upswept arm, which mirrors the arced shape of his congregation. Recalling Johnson’s Jesus and the Three Marys and other works by Lawrence, the figure of God has a noticeably enlarged hand. A common feature within his Builders series, the enlarged hands, like the toolbox, act as highly visible instruments of work and creation. God and his congregation have finished their collective work, and while the churchgoers display their tools, God showcases his hand as an instrument of divine creation. Through this series, Lawrence has transformed the black body from a victim of racial violence to a powerful instrument of progress, a reversal emphasized through an absence, rather than a presence: the final panel is the only one that does not feature a figure shedding tears. The exclusion of such imagery points to Lawrence’s faith by allowing religion to soothe the ailments of a fragmented society.

Concluding Creation

“…I attended Sunday School, and I remember the ministers giving very passionate sermons pertaining to the Creation…As I was doing the series I think that this was in the back of my mind, hearing this minister talk about these things.”[30] Jacob Lawrence’s comments on his Genesis series begin to uncover the true depth he achieved within these works. Generations of storytelling culminate in a pictorial sequence that illustrates the religiosity of millions of Southern black migrants who sought out the North to join their Christian siblings. Employing a similar visual style to William H. Johnson, Lawrence references his forebears while reorienting that standard narrative to one of black empowerment. For Lawrence, religion is a tool that builds communities and provides them with the instruments to enact societal change. Relying on his own experiences as a youth in Harlem, Lawrence personifies his own religious upbringing within the black God of the Genesis series. Like the many migrant families who journeyed north, we too are taken on a journey of creation, community, and change, as Jacob Lawrence takes us with him to Sunday School.

- The Great Migration was the mass movement of nearly 6 million African Americans out of the South and into the rest of the United States, most notably the Northeast and Midwest. This migration occurred from roughly 1916 to 1970. ↵

- For more information on Jacob Lawrence’s Harlem series, see Patricia Hills, “Home in Harlem: Tenements and Streets,” in Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (2009): p. 169-204 ↵

- Peter T. Nesbett, Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints (1963-2000), A Catalogue Raisonne (Seattle: Francine Seders Gallery, 2005), 50-51. ↵

- Allan Edmunds, “The Printed Image: Process and Influences in African American Art,” in The Routledge Companion to African American Art History, ed. Eddie Chambers (Routledge, 2019), 395. ↵

- For more information about black printmaking, see https://www.bookprintcollective.com/ ↵

- Edmunds, "Printed Image," 399, 404. ↵

- Spiral was an African American art collective founded by Romare Bearden, Charles Alston, Norman Lewis, and Hale Woodruff. For more information on Spiral, see Connie H. Choi, “Spiral, the Black Arts Movement, and “Where We At” Black Women Artists,” in Where we At? Black Radical Women 1965-1985: a Sourcebook, p. 26-32. ↵

- “Religious Ceremony at Liberty Hall that Corrects Mistake of Centuries and Braces the Negro,” The Negro World, September 6, 1924, 5. ↵

- Lord Primate is akin to an Archbishop. ↵

- “Religious Ceremony,” The Negro World, 5. ↵

- Kymberly Pinder, "'Our Father, God; Our Brother, Christ; or are we bastard kin?': images of Christ in African American painting," African American Review 31, no. 2 (1997): 223-33. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Kymberly Pinder, “Black Grace: The Religious Impulse in African American Art,” in The Routledge Companion to African American Art History, ed. Eddie Chambers (Routledge, 2019), 193. ↵

- “Religious Ceremony,” The Negro World, 5. ↵

- Nesbett, The Complete Prints, 50. ↵

- Kristin Schwain, “Creating History, Establishing a Canon: Jacob Lawrence’s The First Book of Moses, Called Genesis,” in Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art, ed. James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 168. ↵

- For more information on Jacob Lawrence’s interest in theatricality, see Patricia Hills, “The Double Consciousness of Masks and Masking,” in Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (2009): p. 205-230 ↵

- Pinder, “Black Grace,” 194-195. ↵

- Schwain, “Creating History,” 170. ↵

- Ibid, 168. ↵

- Ibid, 171. ↵

- “Twenty Questions: Jacob Lawrence,” Philadelphia City Paper, May 8-15, 1997. ↵

- Schwain, “Creating History,” 171. ↵

- Pinder, “Black Grace,” 193. ↵

- Amy K. Hamlin, “Toward an Aesthetics of Transcendence: William H. Johnson’s Jesus and the Three Marys,” in Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art, ed. James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 85. ↵

- Ibid, 87. ↵

- Ibid, 75. ↵

- Schwain, “Creating History,” 166. ↵

- Nesbett, The Complete Prints, 50. ↵