2 The Fruit of Labor

Jacob Lawrence and Still-Life

Ryan Hawkins

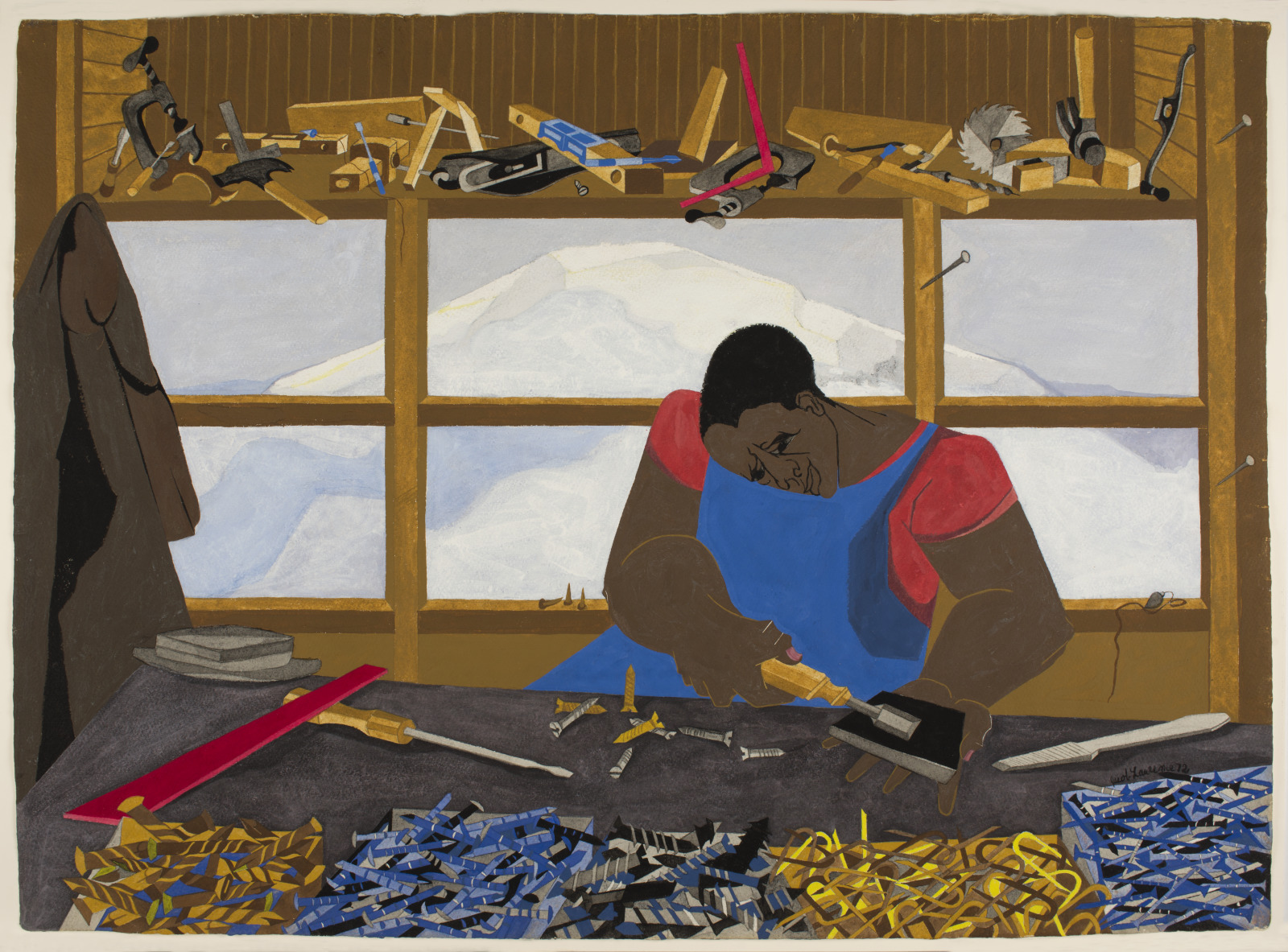

In Jacob Lawrence’s painting Builders No. 1, we find a carpenter seated at his work bench sharpening his tools and organizing his workspace (fig. 1). This piece from 1972 was painted shortly after Lawrence’s move to Seattle to begin teaching at the University of Washington’s School of Art + Art History + Design[1] and rightly features the iconic image of Mt. Rainier in the window behind our subject. Builders No. 1 utilizes the same motif of tools present in countless other paintings found in both his earlier work and the works to come after his move to Seattle. However, this painting remains distinct through a prominent use of Seattle imagery, and a unique depiction of tools that work in tandem to tell a story of labor that leads up to this very moment.

Over the course of Lawrence’s long career, he utilized tools in a variety of different ways. In his Migration Series we see workers actively using their tools in a similar effect to genre painting, exemplified by the fourth panel.[2] The tools are highlighted by Lawrence’s use of primary colors and stand out from the picture plane despite their simple depiction. This use of tools is quite literal, showing them being deployed in the process of labor. In contrast, other paintings implement tools in ways that are less direct and more conceptual. This is especially true in the Eight Studies for the Book of Genesis series,[3] where the creation of the world seems to be linked to the small tool box placed in the background of every panel. In Builders No. 1, both approaches to the tool motif come together to depict the lifetime of work that led to this landmark phase of Lawrence’s career and the beginning of his Seattle residency.

In 1978, The University of Washington hosted its 3rd Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture. The faculty member chosen to give this speech was said to have demonstrable impacts of their achievements on their profession and on society in general, and of all the esteemed faculty members nominated to give the speech, “no other fits this criteria like Jacob Lawrence.” In his speech entitled, I Wonder as I Wander, Lawrence dives into his time spent in New York city as a budding artist in the 1930s. He notes how the vibrant life and bustling streets of Manhattan that he wandered every day influenced the community-centric colorful depictions of life we observe in his paintings. His wanderings, from north to south to east to west covering every street corner of New York, opened his eyes to the community he found himself living in following his parents’ migration from the rural southern United States. The people he meets, the buildings, the movement; life as he sees it lives on as he meanders:

“And so I continue day after day week after week as I make these rounds…I do not stop at 110th street, I continue on moving south on 5th Avenue through the 90s through the 80s until I arrive at 82nd Street and 5th Avenue, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A psychological barrier has now been broken. I enter the museum and I am amazed to see the artworks, sculptures, paintings, prints, and I focus on the paintings because by this time I had been painting and working very intuitively without guidance… and so I enter the Metropolitan and I am awed by what I see there.”[4]

Lawrence regarded the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a place of inspiration in the early years of his artistic career. During the 1930s, the time of Lawrence’s most frequent visits, The Met was going through substantial changes due to the financial turmoil of the great depression. Philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated millions of dollars to support the museum’s output of exhibitions to attract more visitors in times of record low attendance. The museum was trying desperately to pull people in to generate revenue, through enticing new collections and the establishment of the Cloisters.[5] The intriguing developments at the Met during the years Jacob Lawrence was frequenting the streets of New York in his “wanderings” probes the question: what did Lawrence see during his visits?

Firstly, The Met Showcased a large amount of medieval works and artifacts due to the installment of The Cloisters.[6] In addition, according to the Met’s record of past exhibitions and acquisitions, a number of ancient artifacts from Japan, Egypt, and China, collections of furniture and oriental rugs, and displays of ancient bronzes and armor were added to the museum’s collection in the 1930s. Interestingly enough, there is a limited number of exhibits centered around painting, which Lawrence stated he was especially interested in during his visits. The majority of exhibitions feature ancient artifacts and décor, but include one exhibition that stands out, Paintings and Prints of the Italian Baroque Era.[7]

In the Distinguished Faculty Lecture, Lawrence recalls his impressions of the paintings he beheld at the Met: “I don’t know how the artists achieved this, the grain in the wood, the grain running through a piece of marble, taking a shape and creating the illusion of weight”.[8] He goes on to describe his awe at the hyper-realistic depiction of objects and the artist’s technical capabilities to transform three-dimensional objects onto a two dimensional picture plane. Given these interests, it’s likely that still-life, characterized by lavish and realistic depiction and a prominent genre in Baroque art, must have struck a chord with Lawrence. These depictions of glossy, delicious fruits and beautifully naturalistic renderings of flowers would seem far removed from his typical style, which was often described as ‘cubist’ and strays especially far from the illusionistic realism found in Baroque art.[9]

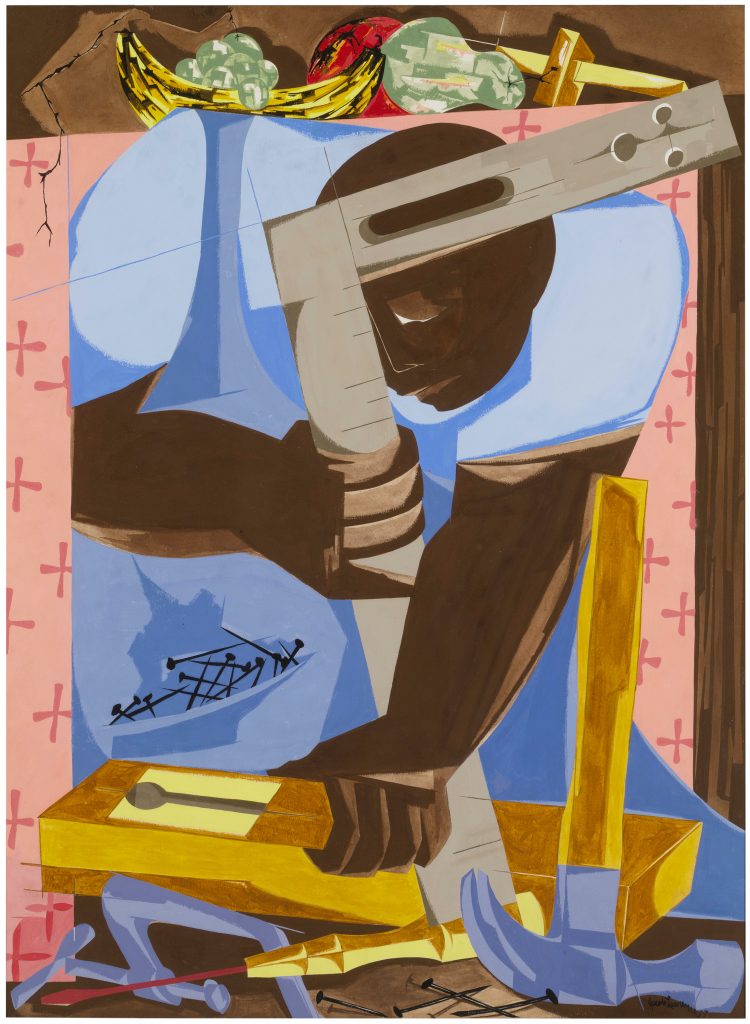

Despite the apparent stylistic mismatch between 20th-century cubism and 18th-century Baroque naturalism, Lawrence implemented signature characteristics of still-life imagery into his work on several occasions. An example is the 1957 painting Cabinet Maker, which shows us a carpenter hard at work with his various tools laid out in front of him (fig. 2). Above him lay an assortment of fruit–a pear, apple, banana, and bunch of grapes– rendered with a distinct sheen absent in the artist’s other depictions of fruit. They are balanced at edge of the shelf which frames the composition, a placement of that seen in paintings like Caravaggio’s iconic Basket of Fruit with their glimmering shine and appeal (fig 3). The fruits hovering above the hard-at-work carpenter seem seem removed from the scene altogether. Spatially, how could these objects exist without topping down onto the carpenter? Do they exist simply to look pretty, to decorate the picture plane? Why would Jacob Lawrence choose to couple a scene of a carpenter laboriously hunched over his work table with this arrangement of produce? To answer this question, it is important to understand the meanings that have traditionally been attached to the genre of still life throughout art history. In the tradition of Still-life across many regions of Europe, specific objects carry different meanings and significance. They exist partly as a coded language of sorts, conveying tone, emotion, or allegorical elements to a painting given each object’s unique connotation. For example, in Italian Renaissance and Baroque eras, apples often represent the Biblical theme of original sin, anemones represent the themes of sorrow and death, and the rose often represents victory, pride, and passion just to name a few.[10] Lawrence is using a collection of objects unique to his own aesthetic eye, and assigning meaning to the presence of these objects to help craft a narrative around the subject matter he chooses to depict.

By juxtaposing tools and the idealized and art historically significant motif of fruits that rest atop the composition, Lawrence draws a connection between labor and beauty, exhaustion and celebration. The result is a shift in tone from one of somber overwork to a glorification of the intrinsic value of labor.

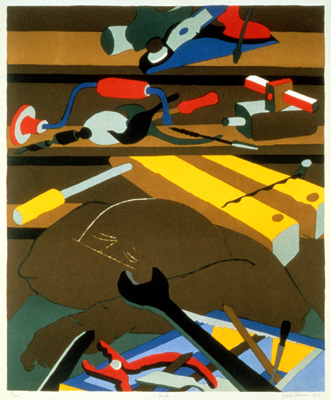

In a 1977 interview with Clarence Major regarding how Lawrence approaches a new painting, Lawrence states, “…when I am working I have a statement, I have something I want to say in my work. I say it according to my own ability as an artist, in my own style”.[11] Considering the fact that Lawrence uses his work to make a statement, paintings like Tools —made the same year of this interview—likely have a deeper meaning despite the fact that the majority of the painting consists simply of tools scattered around a cluttered work room (fig. 4). Tools depicts a tired laborer slumped over his table presumably after a long day’s work surrounded by an array of colorful tools displayed on the table before him and the shelves in the background. Lawrence has painted this man to be the exact same shade of brown as the background of his workshop, making the form of the man hard to decipher. The presence of the tools greatly overshadows the presence of the human figure, pulling our attention to the laborer’s work over the state of the human being doing that labor. By highlighting the color of the tools and minimizing the presence of the man, Lawrence questions tendencies to value the products of labor over the laborer itself. These simple tools that are littered throughout many of Lawrence’s paintings, especially those concerning laborers, are the catalyst for Lawrence making his statement on matters of labor and the working class.

Regarding his affinity for tools in his work, Lawrence has stated, “It’s a beautiful instrument, the tool, especially the hand-tool. We pick it up and it’s so perfect, it’s so ideal, it’s so utilitarian, so aesthetic, that we turn it, we look at it…I always think of the tool as an extension of the hand.”[12] Lawrence sees a beauty in the personal nature between the worker and his tool, specifically rudimentary tools that don’t rely on mechanized elements like drills or bandsaws. His affinity for hand tools is especially interesting when considering the development of electric power tools, which were invented around 1895.[13] Since power tools had decades to develop before Jacob Lawrence was even born and became the standard in terms of building and construction during the times Lawrence began depicting labor extensively in his paintings, why do electric power tools make no appearance in Lawrence’s work, even in the paintings made late into the 20th century? The mechanization of tools used in construction is directly linked to the expanding industrialization of the west, as technology began to develop, the method of construction became advanced and streamlined. Rudimentary tools that required a significant amount of experience to be able to utilize effectively were replaced by power tools that could do the same job in a quicker amount of time. In short, industrialization dulls the beauty that people like Jacob Lawrence see in tools. Mechanization severs the intimate connection between the laborer and the tools of his craft. He spends less time drilling in each screw, his thoughts are drowned out by the heavy noise produced by a bandsaw, a nail gun negates the need for a hammer entirely. Instead of painting the tools that were used in the urban landscape surrounding Lawrence, he chooses to paint these objects in a meaningful if less direct way. The tools that surrounded him in both Harlem and Seattle become idealized, much like Caravaggio’s grapes. While Tools can be seen as a melancholy reality of the working class struggle, Lawrence’s idealized depiction of tools is used to juxtapose the state of the worker with the methods of creating his work to make a statement about the commodification of labor. Additionally, the tools incorporated in Cabinet Maker further the narrative of highlighting the beauty of the laborer.

The tools featured in Builders No. 1 are also a gateway to a deeper understanding of its themes and messages, but supply a distinctly different impact. In contrast to the demeanor of the man in Tools, the carpenter featured in Builders No. 1 sports a thoughtful smile and focused brow as he works on sharpening and maintaining the tools in his work space. Before him, lay five neatly organized bins that hold sorted and color coded screws and nails. In the background above the window lay a large array of miscellaneous tools of varying shapes and sizes that all disobey the natural laws of gravity and seem to stand upright to showcase their details. There are three distinct groups of tools featured in this painting: what’s behind him, what’s being used, and what lies in front of him, granting this piece a reflective tone given the inclusion of Mt. Rainer, an iconic symbol of the pacific northwest, and a symbol of the new home Lawrence has found in Seattle in the large window taking up the majority of the pictorial plane. The tools behind the carpenter sitting on the shelf are spread out chaotically and feature a more diverse collection of tools for a variety of uses. These tools are collected in one unorganized mass, barely holding on to the shelf that supports them. This depiction is typical of Lawrence’s established tradition in painting tools that calls the reader to remember the legacy he has established with his aesthetic.

The carpenter in Builders No. 1 is actively engaged, sharpening his tool kit–not unlike Lawrence when he painted this scene. Jacob Lawrence’s career past the point of his relocation to Seattle has been routinely dismissed by scholars as a downward trend of loss of color, energy, and edge.[14] Lawrence’s choice to depict a man in Seattle honing his craft, sharpening his chisel, and preparing for the labor set before him can be seen as a challenge to this very notion. Lawrence is not idly sitting by letting his career mellow into obscurity, he’s using a new opportunity and a new setting to start on a brand new chapter.

The neatly organized bins of screws that lay before him are very unusual in comparison to Lawrence’s tradition of depicting tools in his paintings. He often paints tools to be scattered around in a chaotic mess; teetering off the edges of shelves and tables, exemplified by his 1982 painting, Eight Builders.[15] Even though Lawrence doesn’t make a habit of organized tool depictions, this change in his usual style of depicting tools reflects the major change in career path that is set before Lawrence, a time of reflection, mentorship, and stability. Made in 1972, this painting serves as a benchmark in his career given that it is the first of his known works to explicitly feature Seattle. This moment in Lawrence’s life was a time of intense change given his drastic relocation across the country, and a new career path. Even so, it cannot be called a self portrait: Lawrence was not a carpenter, and the works that do fit the genre show a different figure.[16] Rather, it might be seen as a portrait of a stage in life, a culmination of events experienced over the years. Even if this painting isn’t meant to be a self portrait, there is a personal nature to the piece. What sets Builders No. 1 apart from Jacob Lawrence’s other paintings concerning labor, is the personal parallels present between the work depicted, the present state of the painter’s life, and significant events in his career. The unique symbolic meanings hidden in the tools of this work aid in the viewer’s reflection on the career of this magnificent painter. He has climbed the mountain, pondered on his accomplishments, and forged a path to further his artistic journey in a brand new city.

Looking back at the expression of the carpenter, we can see that he is content with his current state. Contrary to Tools, we see that Lawrence has used tools to tell an optimistic story of life, work and success. The view of Mt. Rainier mirrors the carpenter’s strength, he has climbed the mountain and is ready to reflect on what he’s achieved, yet still sharpens his chisel ready for the next task. Lawrence has worked his way to this milestone in his long artistic journey, and is able to pause, not to lay down his tools forever, but reflect on the fruit of his labor, and the opportunities that lay before him.

- Cotter, Holland "Jacob Lawrence Is Dead at 82; Vivid Painter Who Chronicled Odyssey of Black Americans". New York Times. June 10, 2000. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob. All other sources of labor have been exhausted, the migrants were the last resource, 1940-41, Casein Tempera on hardboard, 18 in x 12 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. David M. Levy. ↵

- Lawrence Jacob. Eight Studies for the Book of Genesis, 1989, Gouache on paper, 75.6 x 55.9 cm. The Walter O. Evans Foundation for Art and Literature. Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle WA. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob. “I Wonder as I Wander” (3rd Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture, University of Washington, Seattle WA, October 5, 1978). ↵

- Rudnick, Allison. “Finding Inspiration in Dark Times: The Met During the Great Depression.” metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 24, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2020/met-depression-years. ↵

- “Medieval Art and The Cloisters.” metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/medieval-art-and-the-cloisters. ↵

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. “The Metropolitan Museum of Art Special Exhibitions, 1870-2017.” metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017. https://www.metmuseum.org/-/media/files/art/watson-library/museum_exhibitions_1870-2017.pdf?la=en. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob. “I Wonder as I Wander” (3rd Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture, University of Washington, Seattle WA, October 5, 1978). ↵

- Stokes Sims, Lowery “The Structure of Narrative: Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence’s Builders Paintings, 1946-1998,” in Over the Line: the Art of Jacob Lawrence, 201-228 ↵

- Ferguson, George. Signs & Symbols in Christian Art. London: Oxford University Press, 1980. ↵

- Major, Clarence, and Jacob Lawrence. "Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, The Expressionist." The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977): 14-27. Accessed June 8, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41067822. ↵

- Messinger, Lisa Mintz, and Lisa Gail Collins. Essay. In African American Artists, 1929-1945: Prints, Drawings, and Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 61. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003. ↵

- “1895: The Year the Power Tool Was Born.” Spark Energy. Spark Energy, March 14, 2019. https://www.sparkenergy.com/when-were-power-tools-invented/#:~:text=In%201895%2C%2016%20years%20after,world's%20very%20first%20power%20tool. ↵

- Hills, Patricia, and Jacob Lawrence. Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2019. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob. Eight Builders, 1982, Gouache on paper, 33 x 44.75 in, Seattle City Light 1% for Art Portable Works Collection. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob. Self-Portrait, 1977. Gouache and tempera on paper, 23 x 31 in. (58.4 x 78.7 cm). National Academy of Design, New York Artwork © Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, courtesy of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation ↵