9 Experience in the University

Mingjie Ma

Introduction

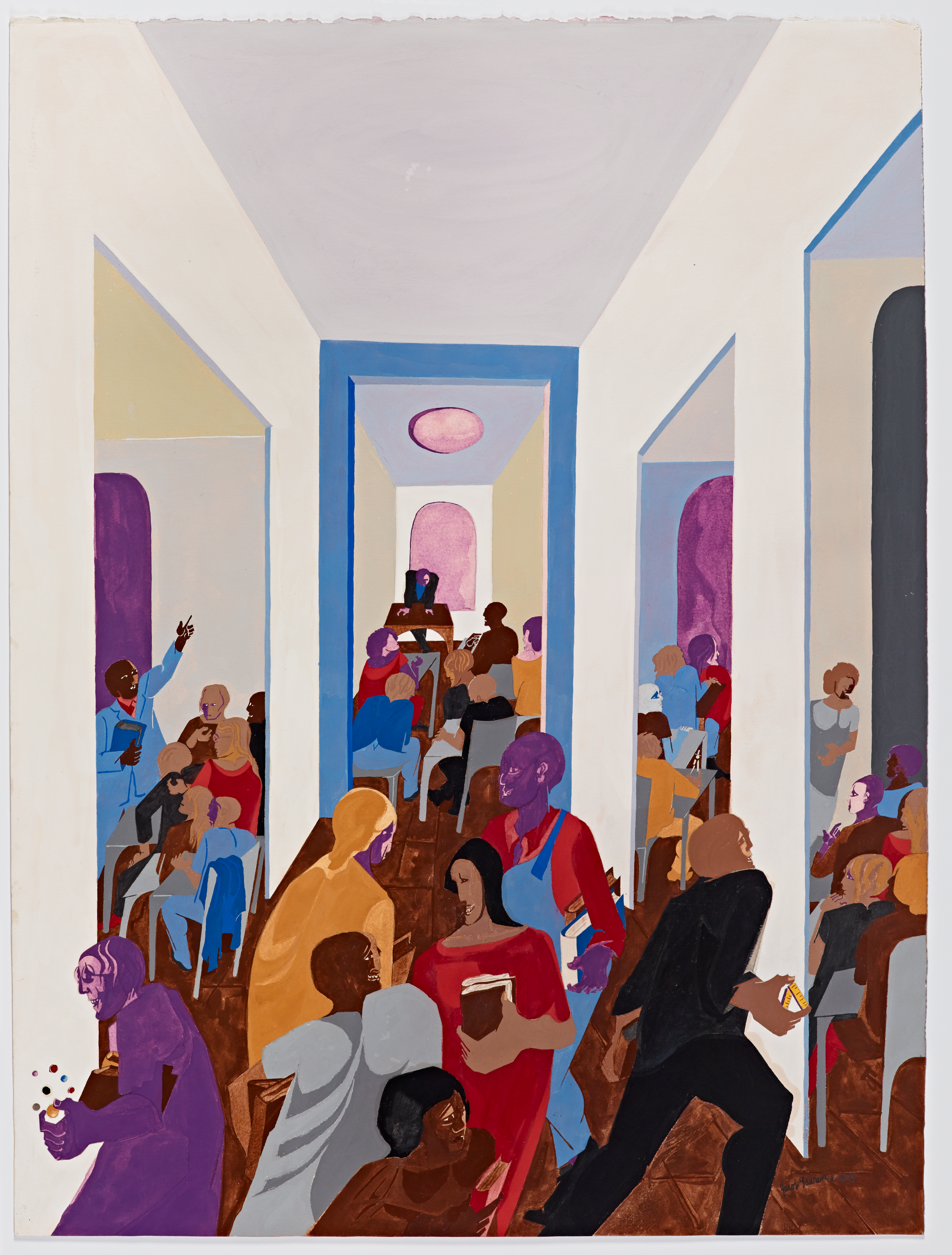

A hallway with vivid white walls, a diverse group of people walking towards you with books and tools in their hands, rushing to get somewhere. You can peek into the classrooms on both sides of the hallway through the open doors: instructors teaching vigorously with their hands gesturing, students listening attentively, and some engaged in heated discussions. The sound from several classrooms and the busy crowd around you blend in, forming a chaotic yet harmonic noise: that was my first impression of Jacob Lawrence’s painting University (fig. 1).

“This is called University, I don’t think I need to comment on that. I see this day in day out, so how could I not paint it?” Jacob Lawrence introduced the painting like this during his 1978 Distinguished Faculty Lecture at the University of Washington (UW).[1] Dated in 1977, the painting was produced during his years as a faculty member at UW, and drew inspiration from his experiences at the Seattle campus as well as other institutions in which he had previously studied and taught.[2] It is a constructed reality that combined his experience and philosophy related to the subject matter, as he once wrote in “My Ideas on Art (Painting) and the Artist”: “My belief is that it is important for an artist to develop an approach and philosophy about life – if he has developed this philosophy he does not put paint on canvas, he puts himself on canvas.”[3] In order to provide a more holistic and historically-specific understanding of this painting, Jacob Lawrence, and his philosophy in teaching, the socio-historical context of African American educators, and the value of African American struggles; this paper situates University within the specific contexts of African Americans’ access to higher education in the US, Lawrence’s own position within academia, and his experiences as both student and educator.

Jacob Lawrence and Education

Jacob Lawrence’s first formal encounter with art education was in 1930 at age thirteen when he attended a day-care program after school at Utopia Children’s House (UCH).[4] The arts and crafts program at UCH was established by James Wells, who learned avant garde pedagogical theories from his Columbia University Teachers College education and implemented it in the program.[5] Wells set up the classroom like a workshop – without settings that indicate the instructor’s authority – and encouraged experimentation with different mediums and the idea of art.[6] Under this educational environment that Wells built, Lawrence met his mentor Charles Alston, who supervised the program at the time.[7]

Lawrence continued to study with Alston throughout the 1930s and eventually entered the WPA Harlem Art Workshop, where he stayed until 1940.[8] Alston’s pedagogy aligned with Wells, and in addition, he was also influenced by other pedagogical theories from his time in Columbia, mainly John Dewey and Arthur Wesley Dow, that he employed when teaching Lawrence.[9] Dewey’s philosophy focuses on “learning by doing” and advocates that the teacher’s role is to assist students on the technical side of studying rather than assign them what subject to learn and what works to do.[10] Dow, chairman of the Fine Arts program at Columbia, championed the idea that fine art and decoration share the same principles of design and emphasized art can be found in everyday life, such as an object’s pattern and shape and the visual relationship it may have with its environment.[11] Lawrence recalled Alston’s teaching as not defining right or wrong but as “a support that was very, very important – that what I was doing, the way I was seeing had validity, it was very valid.”[12] All of the above suggests that Lawrence’s art education was unlike any formal art education and complex in nature. He once said, “During my apprentice days I wasn’t grounded so much in the technical side of painting as I was in the philosophy and subject I was attempting to approach”, a philosophy of art that calls for experimentation, experience, and exploration in real life.[13] Informed and influenced by many novel pedagogical theories of his time, Lawrence’s education in turn also lay the groundwork for his later pedagogical development.

Lawrence’s approach to painting was shaped not only by his teachers but also by his learning environments. The WPA workshop was relocated to Alston’s studio in 1934, known as the Studio 306.[14] It was not just a workshop but a gathering space for artists and established Harlem intelligentsia.[15] In an interview, Lawrence recalled hearing discussion on topics other than art: “during the ‘30s there was much interest in black history and the social and political issues of the day – this was especially true at 306.”[16] The emphasis on learning about black history and doing research work concerns the community’s interest reflected in Lawrence’s early works. He painted series on Toussaint L’Ouverture, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman with a historical approach based on extensive research in the library.[17] What stuck with the young Lawrence in time of 306 is the awareness of concurrent theoretical debate and social consciousness that fueled his creation in the years following.

By the time Lawrence left studio 306, he already won a few prizes and fellowships, had solo exhibitions, and became a rising figure of the New York City art scene.[18] But what brought him nation-wide recognition was his Migration series painted during 1940 and 1941. The Great Migration was a movement of hundreds and thousands of African Americans relocated from the Southern United States to the North, fled from strict segregation laws and sought better livelihood.[19] Depicting the movement which his family was a part of, the series includes not only scenes of the migration process but also the cause and effect of such migration, integrating history with Lawrence’s personal reflection.[20][21] The whole series was published in color in a 1941 issue of Fortune Magazine, bringing attention, fame, and credibility to the young artists. His newfound fame kick-started his teaching career. In 1942, Lawrence worked as a summer art instructor at Workers Children’s Camp (Wo-Chi-Ca), it was his first of many educational roles he took throughout his career.[22] Before he became a faculty member of UW in 1971, Lawrence taught in institutions including Black Mountain College (1955), Five Towns Music and Art Foundation (1955-62, 1966-68), Pratt institution (1956-70), Brandeis University (1965), New School for Social Research (1966-68), Art Students Leagues (1967-69), Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (1968-69), and California State College (1970).[23] Out of the ten institutions at which he once taught, seven of them were private institutions that were progressive in ways such as being diverse and inclusive of all races and genders, founded by female scholars, and working on progressive models of education etc. These institutions informed Lawrence’s understanding of what an educational environment should be like and who is included.

Among these institutions, Black Mountain College stands out as Lawrence’s first official teaching position, one that he considered a “milestone” and that initiated him “into the ranks of teacher”.[24] The college was established with a vision to implement John Dewey’s “learning by doing” philosophy.[25][26] It reminded Lawrence of studio 306: teaching was informal, faculty and students were close, everyone was learning something from each other, and an individual approach was encouraged. Josef Albers, a former educator at the famous Bauhaus school, was hired as the first art teacher.[27] Despite Lawrence’s lack of teaching experience, Albers invited him to join the summer faculty and showed Lawrence how to convey ideas analytically. Albers’s ideas about teaching design, color, and the picture plane became foundational to Lawrence’s pedagogy. [28]

Lawrence’s longest and last teaching experience was at UW, a much different one than Black Mountain College. UW is a public state university on the West Coast, and according to Lawrence, it was less competitive compared to private schools in the East.[29] He described his experience at the UW as “pleasant”.[30] Lawrence liked the environment, especially the fact that it supported artists’ individual research, so that his painting did not have to “suffer from teaching”.[31] From 1971 until he retired in 1983, Lawrence was a beloved member of the UW community, and he continued to teach part-time as professor emeritus until 1985.[32]

The particularity of the University

The University depicts a scene of a busy hallway that might seem familiar to many, a chaotic yet energetic environment of learning and doing things. This painting stands out as the only painting titled University, a particular type of institution, and the only education-related painting created in this period that was not commissioned. There is no direct reference to UW, but the symbolic composition and color, books and tools depicted, and the implied pedagogy seen through interaction between students and educators tell us more about his experience in a state university, his education, and his philosophy. Just like he once said: “my work was mainly autobiographical.”[33]

At first glance, the white walls and ceiling not only take up substantial portions of the picture plane but also stand out as the structure of the space that defines the composition. The use of white was no coincidence: it refers to the notion of an ivory tower, a place of privilege.[34] Moreover, the column-like walls on the side, together with the use of linear perspective that form a vanishing point at the center of the painting, also closely resembles the iconic scene of education The School of Athens, painted by Raphael during the height of the Italian Renaissance (fig. 2). [35] School of Athens pictures a gathering of renowned scholars from different times and of different disciplines. Not only does the two works’ composition look alike, the palette used was strikingly similar, and the appearance of books and tools resembles one another.[36] Well aware of Renaissance art, Lawrence drew this parallel to this elite hall of thinkers to suggest that higher education is not accessible to all.[37] During the 1970s, the pursuit of higher education for black people in America was challenging. Until the 1950s, higher education in America was still segregated and upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine that grants legality to the dual system.[38] Black students went to historically black colleges and universities, and white students went to designated schools that only serve them. 1954 marked the turning point of desegregation in higher education, the Supreme Court’s ruling of the Brown v. Board of Education case declared segregated educational facilities unconstitutional.[39] After this decision, the admission rate of black students in white colleges increased slightly. However, the effect was limited because the desegregation requirements on students and faculty were not applied to institutions of higher education.[40] Only until the passage of the Higher Education Act (1965) against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Act (1964), black students were finally legally provided equal opportunity in higher education.[41] Lawrence was aware that his presence in many institutions that he taught in was something quite exceptional. In 1945, there were only 15 African American faculty in predominantly white universities and three decades later the statistics were 4.2%. [42] UW was no exception, there were only 7 black faculty members before 1969.[43][44] If it wasn’t for Lawrence’s success as an artist, he may have had little chance in becoming an educator. It was his privilege, too, to be invited and became a faculty member in higher education.

Beyond the notion of privilege, the white walls and ceiling arrangement can also suggest his philosophy on life – the value of struggle. The arrangement creates a cage-like impression but is an incomplete one. The “cage” does not have a ground and is open on the right, with part of it being confronted by the black and purple figure in the foreground. Classrooms seem closed but there is no door to them. Restrictions and possibilities coexist in this painting, echoing Lawrence’s belief in the value of struggle: “man’s struggle is a very beautiful thing… The struggle that we go through as human beings enables us to develop, to take on further dimensions.”[45] Lawrence’s teaching career was not without struggle. His invitation to the Black Mountain College, located in the Jim Crow south, was partially motivated by the integration effort, and Lawrence did not leave campus during his stay.[46][47] Lawrence was invited mostly by private institutions that were devoted to minorities and championed diversity, accepting a predominantly white state university’s invitation can also be a struggle, but as Lawrence showed in the painting, “when you don’t feel struggle, there is no passion.”[48]

There are other intriguing details in University that reveal part of Lawrence to the viewer. Most of the figures in the painting are holding books, but the purple man on the lower-left corner is holding something like a few floating glass marbles, the black figure on the lower right has a folding ruler, and the gold figure in the second classroom to the right is playing with a compass. Tools are repeated motifs that occur in many of Lawrence’s paintings, but the presence of both books and tools in an educational setting has symbolic meaning. Tools are usually associated with hands-on experience and Lawrence’s own education was centered on that. He has been exposed to John Dewey’s philosophy of “learn by doing” through his mentor Charles Alston and at Black Mountain College.[49][50][51] The idea of education to him was not merely theoretical but of experience that is represented through tools. The juxtaposition with the School of Athens that was introduced earlier also provides another possible interpretation. Tools can be seen as representations of different academic disciplines: the floating marbles resemble atomic models in quantum physics, the compass references mathematics, and the folding ruler evokes architecture – just a few disciplines that Lawrence was exposed to during his teaching at different institutions.

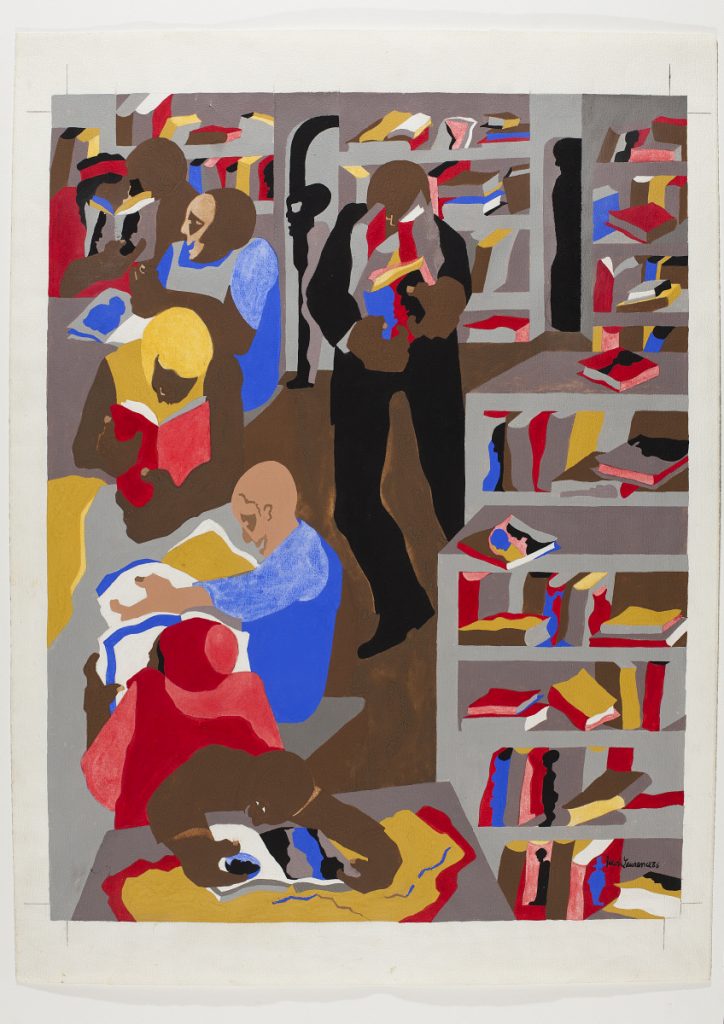

Just like tools, books in Lawrence’s works carry symbolic meaning as well. In the Schomburg Library from around the same period, books are depicted, as seen in many other Lawrence’s paintings, open and in the hands of active readers, engaging in intellectual labor (fig. 3).[52] However, in University, none of the books are being read but held in hands as symbols. Interpreting books and tools as related symbols raises the question of Lawrence’s own beliefs about African American access to education as a path to equality. [53] Lawrence’s stance on this subject is clear as both symbols appear in this environment showing that he saw value in both types of education, an opinion that was probably informed and influenced by his former education which similarly combined the two.[54] He stated as much in a caption to 1947’s A Class in Shoemaking: “knowing the value of an industrial skill as well as an academic education the Negro, for many years, has worked hard to obtain both.”[55] In this brief caption, Lawrence provides the viewer with insight into his own political philosophy on issues related to racial equality.

Lastly, comes the pedagogy visualized in this painting. In the three classrooms on the side of the hallway, students listen attentively to their instructors, who stand in close proximity to them. Other than standing out from the seated crowd, there are no signs of authority. The composition also brings viewers’ attention to the center classroom, where the instructor seems to be listening humbly to the brown figure who is pointing towards himself. Hand gestures, a form of nonverbal communication, are depicted among students and educators to suggest the vocal aspect of communication that cannot be drawn. The lack of hierarchy and free exchange between students and teachers resembles the classroom set up at Utopia Children’s House, the Studio 306, Black Mountain College, and other progressive institutions that Lawrence once taught in. The experience largely influenced his pedagogy and is also evident in the painting where students and teachers blend in visually. When asked about teaching, Lawrence said he always enjoyed the interaction with students, and saw his role as “inspirational encouragement” to them.[56] He did not enforce a certain approach on students, rather, he taught them to explore different mediums, stress the importance of design, and create art that’s about one’s unique “experience” and “feeling” towards an object.[57] In this pedagogical approach, Lawrence built upon what he had been taught by his own mentors, from Harlem to Black Mountain College.

Concluding thoughts

Lawrence’s experience in the university, both literally and figuratively unfolds before the viewer’s eyes. As he said often, he speaks through his work. The composition and color of the painting signal the elite nature of this educational institution and an awareness of his own position of relative privilege, while also finding and grasping opportunities in an environment that might appear restricting at first. The tools and books in the work are symbols of his own education and his stand on concurrent debates. And the interaction between students and educators in the work as an embodiment of his experience and philosophy in the education field.

The topics that Lawrence discussed in this painting, who has access to education, means of education, and pedagogy are still relevant today. Taking access to education as an example, although there is an unquestionable increase in African Americans earning higher education degrees, the number is still not representative of the U.S. demographic.[58][59] Desegregation of education can be traced back to Lawrence’s time, but the progress our society made was still limited. Research of 2018 by the National Center for Education Statistics shows that only 3% of U.S. full-time faculty members are Black and Hispanic.[60] And speaking of UW specifically, only 1.5% of the professorial faculty at UW were Black in 2018.[61] In the summer of 2020, the UW Black Student Union posted their seven final demands, which closely resemble the demands made by the organization in 1968, just before Lawrence’s arrival on campus. Both include hiring more black faculty.[62] It is daunting to see the same issue persist as of the time that the painting was produced, but it is also the power of art to keep its audience alert and inspired from decade to decade. As Lawrence once said: “I always want to keep my work alive and moving. Maybe the new reality is the result.”[63] If the 1977 University is still not yet the reality, as the contemporary audiences viewing this painting, it is our responsibility to reach for the tools and books to keep the discussion “alive and moving” until the walls are dismantled.

- Jacob Lawrence, "I Wonder as I Wander". (Third Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture, University of Washington, Seattle WA, October 5, 1978). ↵

- Nesbett, Peter T., and DuBois, Michelle. Over the Line : The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence. Complete Jacob Lawrence (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), p. 25-65. ↵

- Black Mountain College Records, Faculty Files, Microfilm Roll 199, Archives of American Art, 1946. Also cited in Wheat, Ellen Harkins, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter (Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1986), p. 73. ↵

- Nesbett, and DuBois. Over the Line, p. 25. ↵

- Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” in Over the Line, ed. Nesbett, and DuBois. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), p. 98. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 98. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 98. ↵

- Nesbett, and DuBois. Over the Line, p. 26. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 98-99. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 98. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 99. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, "Jacob Lawrence on his mentor Charles Alston," interview by The Philips Collection, video, 0:59, https://youtu.be/rhNRlxeO6ds. ↵

- Black Mountain College Records, Faculty Files, Microfilm Roll 199, Archives of American Art, 1946. Also cited in Wheat, Ellen Harkins, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter (Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1986), p. 73, and Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” in Over the Line, ed. Nesbett, and DuBois. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), p. 100. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 100. ↵

- Lawrence, in an interview with Jeff Donaldson, January 8, 1972, in Donaldson, "Generation '306,'" PhD diss, Northwestern University, 1974. Also quoted in Leah Dickerman, "Fighting Blues," in Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, p. 16. ↵

- Dickerman, "Fighting Blues," p.16. ↵

- Dickerman, "Fighting Blues," p.17. ↵

- Nesbett, and DuBois. Over the Line, p. 27-31. ↵

- Devoy, Maeve, and Allen Raichelle. "Great Migration." In The American Mosaic: The African American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://africanamerican2-abc-clio-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/Search/Display/1407061. ↵

- Dickerman, "Fighting Blues," p.17. ↵

- Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter, p.62. ↵

- Nesbett, and DuBois. Over the Line, p. 32. ↵

- Nesbett, and DuBois. Over the Line, p. 25-65. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence quoted in E. Honing Fine. The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity. (New York: Holt Reinhart and Winston, 1973), p. 150. Also cited in Julie Levin Caro, "Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946," in Lines of Influence, p.131. ↵

- "History," Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, accessed June 1, 2021, https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/history/ ↵

- Caro, "Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946", p. 133. ↵

- Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, "History." ↵

- Jacob Lawrence quoted in A. Berman, "Jacob Lawrence and the Making of Americans." ARTnews, Vol. 83, No.2 (Feburary 1984): p.85. Also cited in Caro, "Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946", p. 141. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, "Interview with Jacob Lawrence," interview by Donald Schmechel on July 27, 1987, video, 1:17:29-1:21:00. https://archive.org/details/spl_ds_jlawrence_01_01. ↵

- Lawrence, "Interview with Jacob Lawrence," 1:13:47. ↵

- Lawrence, "Interview with Jacob Lawrence," 1:17:59. ↵

- Nesbett, and DuBois. Over the Line, 25-65. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, "I Wonder as I Wander" (Third Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture, University of Washington, Seattle WA, October 5, 1978). ↵

- Harry J. Elam. Jr., "Images of Higher Learning: Jacob Lawrence's University," in Promised Land: The Art of Jacob Lawrence, (Cantor Arts Center, 2015), p. 35. ↵

- Monica Ionescu, class discussion with the author, May 27, 2021. ↵

- Nic Staley, peer evaluation with the author, June 3, 2021. Specifically the tool's resemblance. ↵

- Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter, p.132. ↵

- Clifton F. Conrad, and David J. Weerts. "Desegregation in Higher Education." In The American Mosaic: The African American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1757993. ↵

- Conrad and Weerts, "Desegregation in Higher Education." ↵

- Maria Bennett and Stafford Hood. "African Americans in Higher Education." In The American Mosaic: The African American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1757992. ↵

- Bennett and Hood, "African Americans in Higher Education." ↵

- Bennett and Hood, "African Americans in Higher Education." ↵

- Taylor, Quintard. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 18710 through the Civil Rights Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994, p. 223. ↵

- Walker, Dianne Louise. The University of Washington Establishment And the Black Student Union Sit-in of 1968. Thesis (M.A.), University of Washington: 1980, p.47. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, lecture, November 15, 1982, quoted in Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter, p. 105. Also quoted in Patricia Hills, "Epilogue," in Painting Harlem Modern, p. 270. ↵

- Bryan Barcena, "Texture of the South: Roland Hayes and Integration at Black Mountain College in H. Molesworth, et, al., Leap Before You Look. Also cited in Caro, "Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946." ↵

- M. Wilkins. Social Justice at Black Mountain College "Before the Civil Rights Age: Desegregation, Racial Inclusion, and Racial Equality at Black Mountain College," The Journal of Black Mountain College Studies, Vol. 6 (Summer 2014). Also cited in Caro, "Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946." ↵

- Robin Updike, "Modern Master," Pacific Northwest (Seattle: Seattle Times Magazine), June 28, 1998, p. 18. Also quoted in Hills, "Epilogue," p. 270. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” p. 98. ↵

- Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, "History." ↵

- Caro, "Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946", p. 133. ↵

- Hills, "Epilogue," p. 270. ↵

- There are two camps of this subject. On one hand, Booker T. Washington, who started the Tuskegee Institution, championed the idea that equality can be earned through work and practical skill development. While his opponent and leader of the Niagara Movement, W.E.B. Du Bois, calls for liberal arts education and civil rights as means of emancipation. Further reading: Bobby R. Holt, "Booker T. Washington." In The American Mosaic: The African American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1477536. William McGuire, and Leslie Wheeler. "W. E. B. Du Bois." In The American Mosaic: The African American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1404462. ↵

- Hills, "Epilogue," p. 267. ↵

- Quoted in Hills, "Epilogue," p. 267. ↵

- Lawrence, "Interview with Jacob Lawrence," 1:18:32 and 1:20:27. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, in Drawing, at the Henry : An Exhibition of Contemporary Drawings by Eighteen West Coast Artists, April 5-May 25, 1980, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington. Seattle: Gallery, 1980, p. 52-53. ↵

- Bennett and Hood, "African Americans in Higher Education." ↵

- The Condition of Education 2020, National Center for Educational Statistics. Reference URL: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/coe_cpb.pdf. ↵

- "Race/ethnicity of College Faculty," Fast Facts, National Center for Educational Statistics, accessed May 12, 2021, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=61. A complete table of statistics can be found here: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_315.20.asp. ↵

- Board of Regents Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisory Committee Diversity Metrics Data Book (2018), University of Washington, p. 109. This report can be found here: https://depts.washington.edu/dvrsty/BOR/DEI-Data-Book-2018.pdf?_ga=2.70405264.1223729846.1623113253-169521470.1463477398. ↵

- Andre Lawes Menchavez, "A History of BSU’s Demands: Repeating Our University’s Oppressive Past," The Daily, Nov 29, 2020. Read the report here: https://www.dailyuw.com/opinion/bsu/article_637a4448-32bc-11eb-b69a-9779a08acebf.html. ↵

- "Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, the Expressionist." The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977): 14-27. ↵