6 Jacob Lawrence and the Magic of Sight

Grace Fletcher

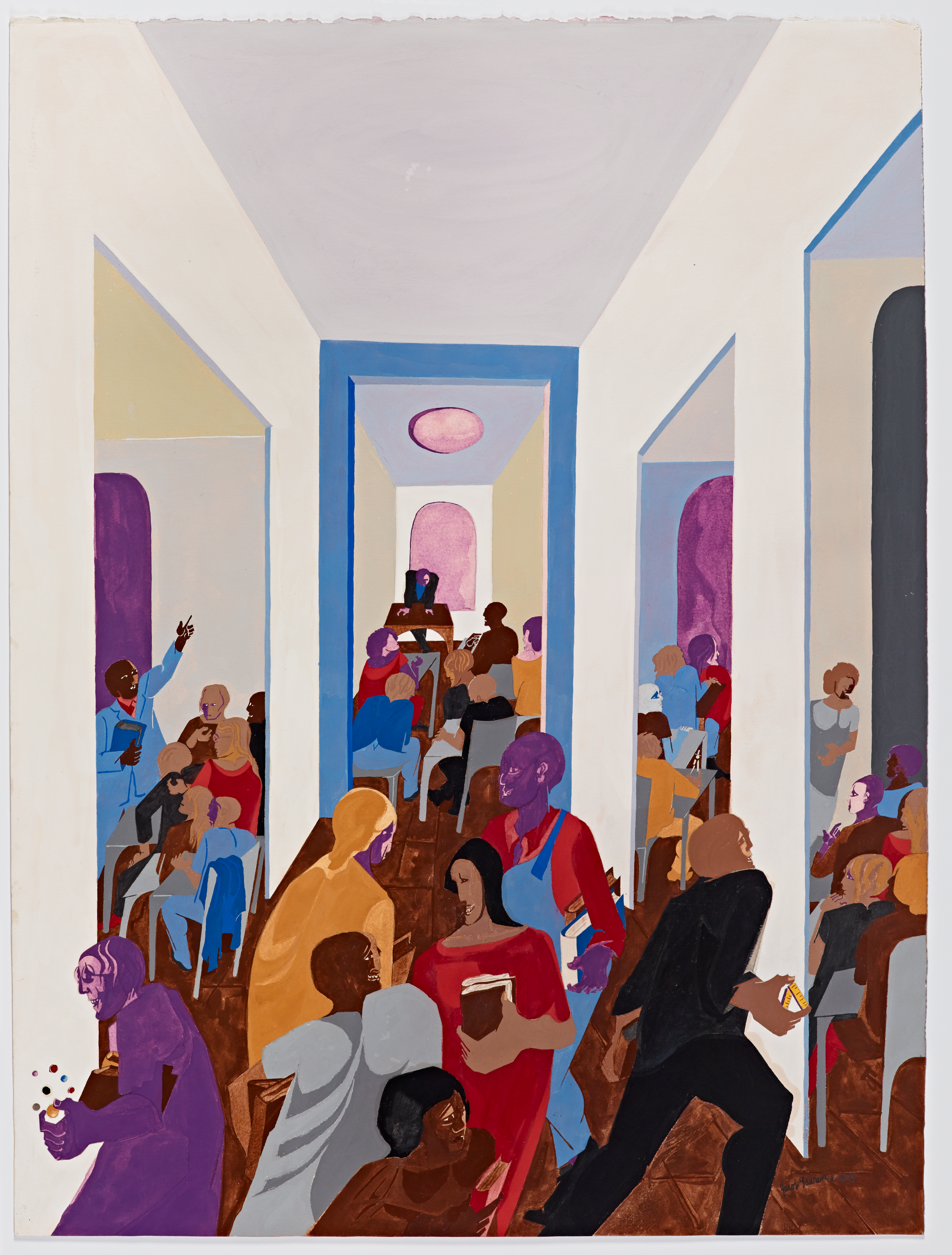

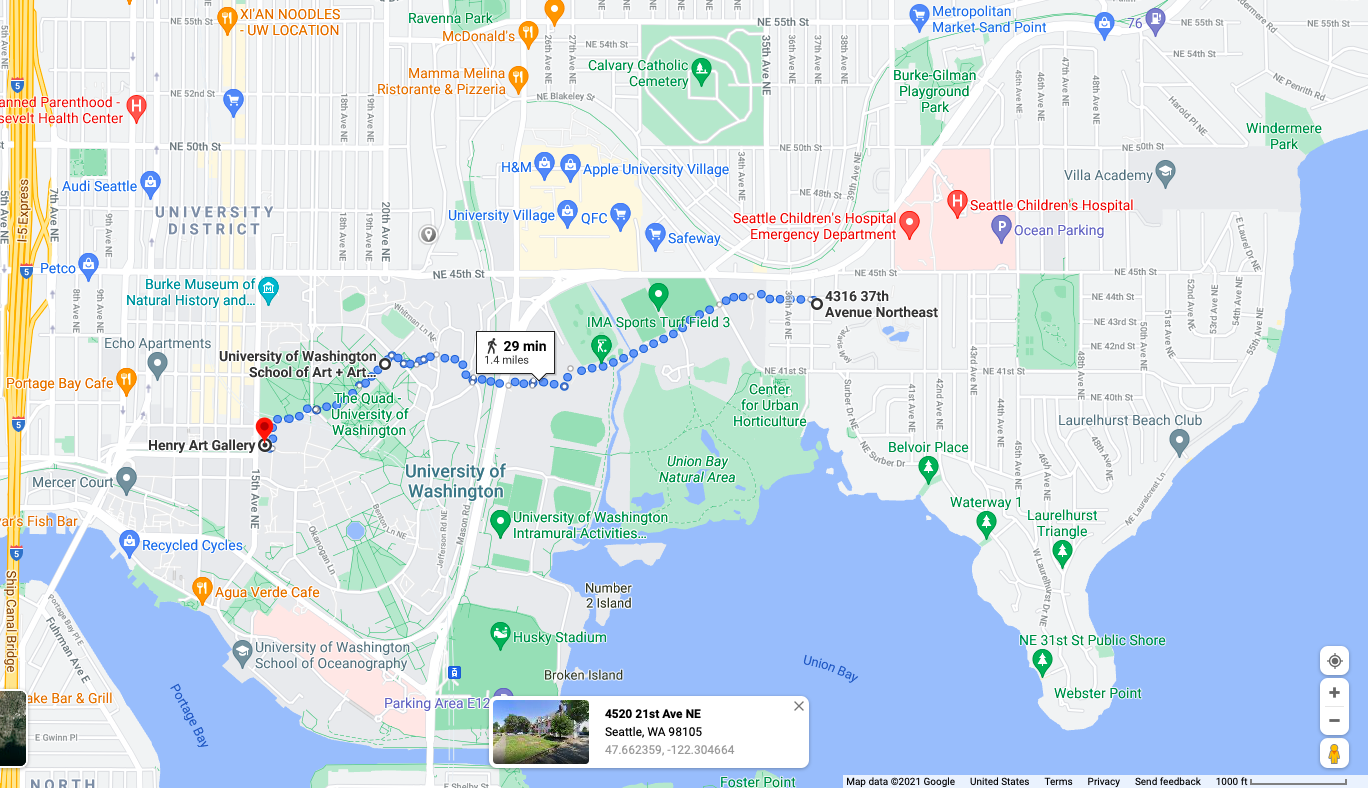

Jacob Lawrence delivered a lecture on his artistic journey at the University of Washington in 1978 with the fitting title “I Wonder as I Wander.” The name was taken from the title of Langston Hughes’ autobiography, and resonated with Lawrence whose development as an artist consisted of “meandering, seeing and observing.”[1] This act of meandering on foot was integral to Lawrence’s life as he never acquired a driver’s license–when offered a teaching position at the University of Washington he requested lodging close enough to walk to campus.[2] Walking was more than just a mode of getting from one place to another–it was important to his artistic development. Through personal interactions within his neighborhood and public spaces, Lawrence was able to see the patterns present in his life more fully, which he incorporated into his art. By combining and pulling inspiration from sights, observations, and locations, Lawrence created art larger than the sum of its parts, with a deep investment in the human experience. This essay will follow Lawrence’s life, art, and teaching on foot to thread together the images of spaces of dialogue, interaction, and work which he frequently returned to and complicated throughout his career. When considered together, his scenes of libraries, classrooms, and labor collectively envision a world of collaboration and creativity built on the substance of experiences. As Lawrence’s work, for instance University (fig. 1) shows us, the daily rhythms and paths of our lives can provide tangible (physical and literal) and intangible (conceptual) tools that inform our education. In University, Lawrence imagines a radical space of learning: one inspired by a life and career engaged in community, experience, and interaction, that explores the intimate and magic relationship between sight and art making. This painting was the destination of Lawrence’s 1978 lecture, and in a similar vein it will be the final destination of this paper.

Stop I: New York, New York

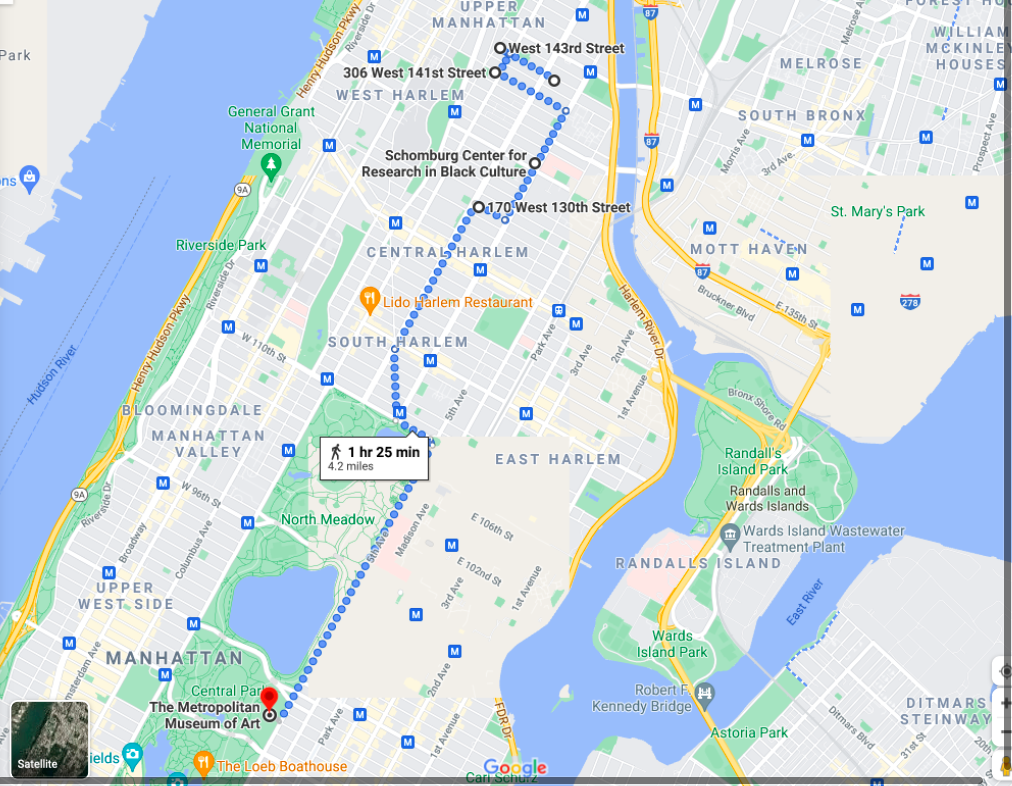

In interviews, Lawrence was often asked about his education (because many believed him to be an untrained genius). Milton Brown’s 1974 introduction to Lawrence’s Whitney retrospective separated Lawrence from his contemporaries by describing him as a singular and untrained genius with no true teachers.[3] This line of thinking posits that Lawrence was conjured out of nowhere and removes him from an artistic lineage. It ultimately undermined the threads of learning through community and experience that Lawrence spoke of in interviews, roundtables and most crucially within his paintings and captions. He spoke of his early learning as beginning in his neighborhood of Harlem, where he drew inspiration from the lives and public spaces he encountered within the community. He emphasized the lessons he learned from talking with and listening to street preachers, communists, librarians and Garveyites (Black Nationalists).[4] In a 1968 interview with art historian Carroll Greene, Lawrence recalled the places he worked in through their location and where he walked to access them. Across the street from where he lived on 143rd street in New York City was a public center where Lawrence first encountered the sculptor, activist, and teacher Augusta Savage, at around the age of fifteen (fig. 2).[5] She would eventually help Lawrence find a position within the easel division of the Federal Arts Projects, a governmental program in support of the arts and the teacher of Lawrence’s future wife the artist Gwendolyn Knight. Prior to meeting Savage, Lawrence attended the Utopia Children’s house on 130th street in 1931, for around three years. It was an after-school arts and crafts program where the classroom was transformed into a studio and the children were encouraged to experiment with the materials available. His early teacher was Charles Alston, a young painter and recent Columbia graduate, who believed that teaching should follow students’ interests and personal affinities.[6]

This freedom to explore materials was furthered when he attended Alston’s Work Progress Administration workshop at Studio 306 on 141st street from 1934 – 1937. The process for Lawrence was one of tangible learning, of “seeing and doing, doing and undergoing.”[7] As Lawrence developed and gravitated toward tempera paints, Alston turned his teaching toward the picture plane (a painting on a two-dimensional surface). He introduced Lawrence to designing based on rugs, an activity created and influenced by the thinking of Arthur Wesley Dow and John Dewey which stressed finding inspiration in everyday experiences and patterns. Dewey saw no separation between fine arts and applied arts and focused on the education of doing.[8] Through copying rugs, Lawrence was learning how to map space. In a 1983 archival interview Lawrence described his work with the picture plane as directly influenced by this mapping of space, as he liked “to put things against things and see them work… and seeing the entire picture plane as a whole and seeing one thing, how it reacts against something else, and the push, the pull of things.” By concerning himself with the entirety of the picture surface, Lawrence began to see each stroke as necessary to the composition. He saw his formal choices of line, shape and color as continuously reacting against one another, and for him to be a successful painter one had to take these reactions into account. Within the picture plane he tweaked patterns to see how forms related to one another, a mode of looking that he carried into the world around him, drawing inspiration from doors, fire escapes, carpets and windows.[9] By equating art with experience, Lawrence began to foster the idea that art clarified meaning contained in the scattered fragments and materials of our lives.

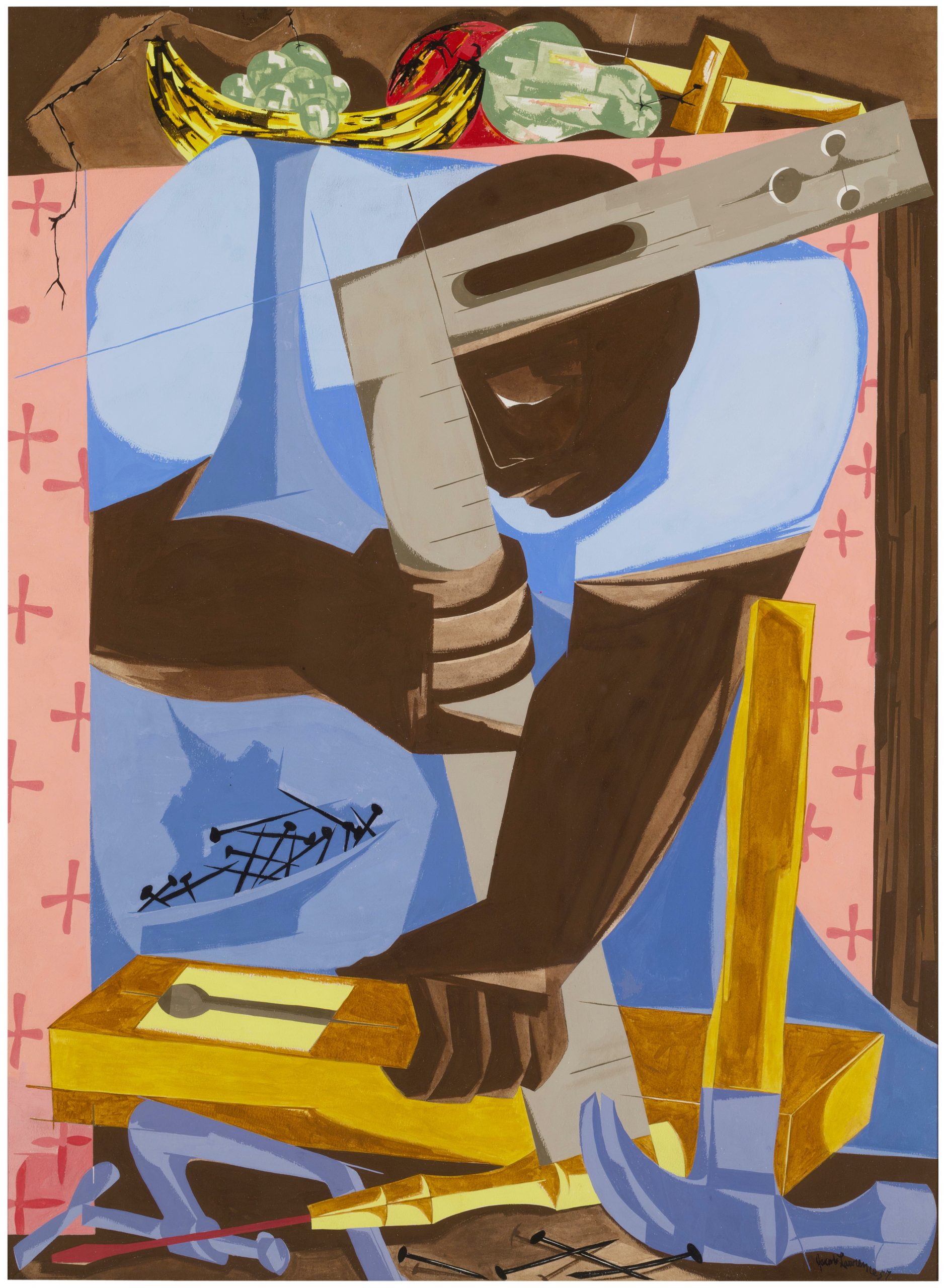

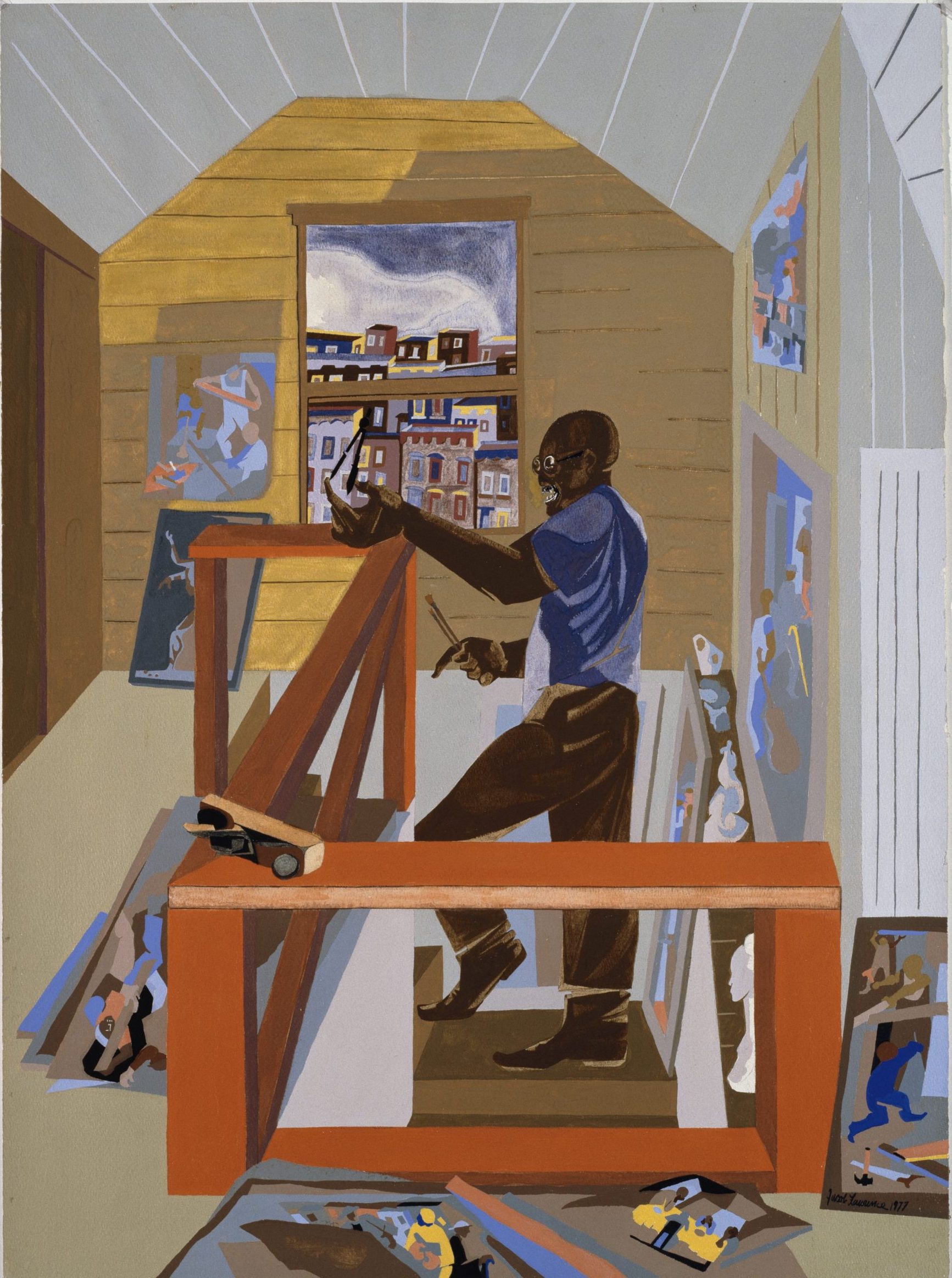

Part of Lawrence’s walk and routine was visiting the New York Public library on 135th street where he conducted research for his series on the life of Harriet Tubman and Toussaint L’Ouverture. Throughout his career he would return to depict libraries as spaces of knowledge by enlarging the books as the tools within those spaces. Lawrence often placed emphasis on tools in relation to specific crafts like in Cabinet Maker, 1957 where a huge hammer lies propped against the worker’s forearm and a massive carpenter square rests within the worker’s hands while nails fall out of his pocket (fig. 3). By using tangible tools to perform his work the carpenter reveals the power of embodied and physical knowledge.

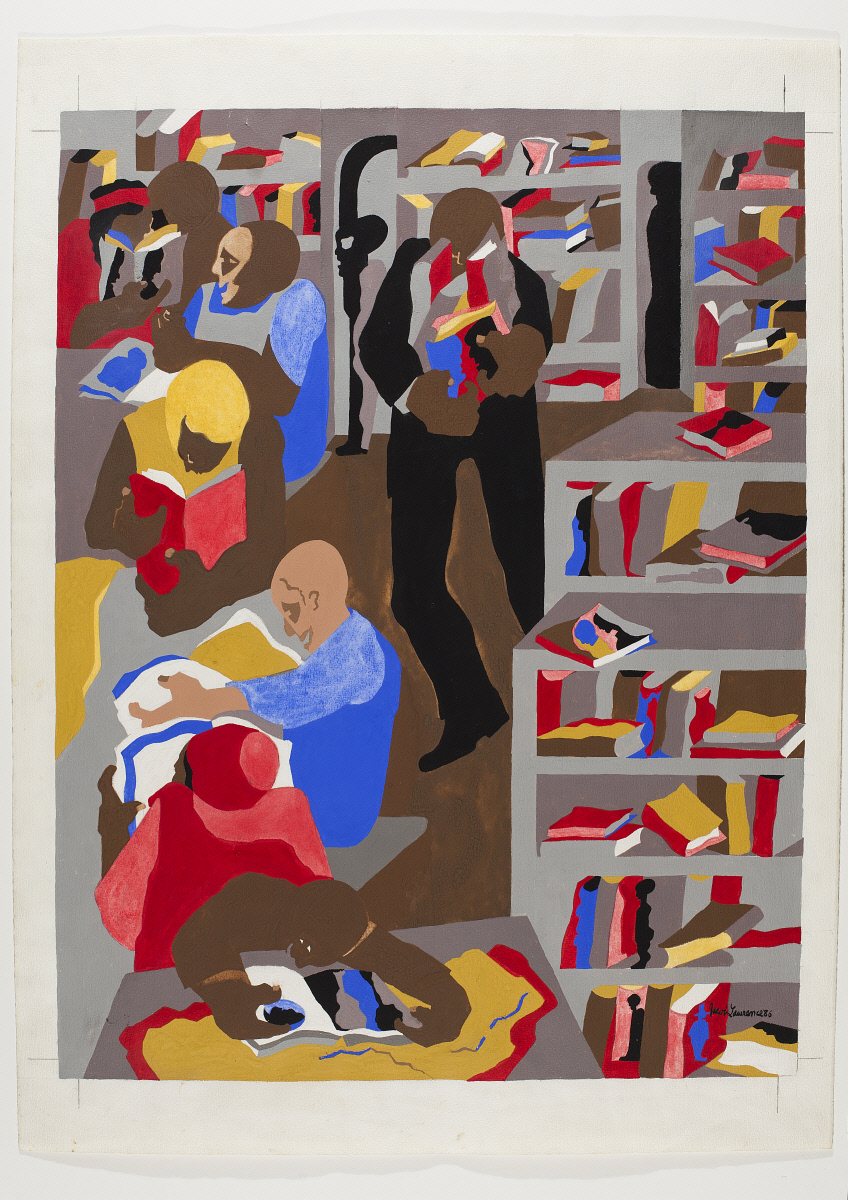

Similarly, the library books are the tools that conceptually inform our knowledge of the world around us, and actively informed Lawrence’s own historical research and subsequent series. This particular library, now the Schomburg Library for Research in Black Culture, held archival material of Black history collected by Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a supporter of the arts and an activist who emphasized the importance of histories and heritage.[10] In 1937, Lawrence paid homage to Schomburg in his painting Library (The Curator), which was done on brown paper with tempera and reveals Lawrence’s limited material as a restriction that dictated his expression (fig. 4).[11] By limiting himself, Lawrence believed the restrictions gave “an experience you wouldn’t get otherwise.”[12] This quote is remarkably similar to a comment he made during his lecture at the UW, where his choice to not drive allowed him to “see things he wouldn’t have seen otherwise.”[13] The repeated use of material and paint was perhaps due to economic necessity, but also reflects a desire to use the same medium in order to further develop his form.

Library plays with the geometric windows, chairs and tables within the space of the reading room, abstracting them into their essential colors and shapes. The arched windows mirror the forms of the circular table and chair, their color only slightly darker than that of the table, making the eye strain to differentiate between the two shades. The subdued palette of dark greens, tans, and charcoals provides a soothing atmosphere of contemplation, yet the chair blocks the viewer’s entry into the scene. Schomburg is turned away from the viewer’s gaze, legs crossed and absorbed in the brightly lit book in his hands that is open and facing us, an available tool of learning. In 1930 the national literacy rate for the Black population was eighty-three percent compared to the white population who had a literacy rate of ninety-eight percent.[14] This disparity between the two populations reveals books as tools that could not be accessed by all. Here literacy becomes the intangible tool that opens the space of the library, like a key. Lawrence returned to the library repeatedly throughout his life, layered visits that informed his paintings. Fifty years after 1937’s Library, he returned to the space (fig. 5). In this iteration there are multiple figures back-to-back, almost touching and stacked on top of each other. In contrast to the subdued and low-contrast palette of the 1937 composition, mostly primary colors brighten and expand our view of the library’s physical space. In this piece, there is a greater sense of community and interaction. Libraries are not only spaces for gathering information but also for gathering communities. Their history and public communal space is as much a tool as the books they contain. In this painting learning through books and through community become equally important in the accumulation of knowledge. What do we miss when we only look at text, or in this case, when we only view libraries as individual spaces of learning where people conduct their learning independently, sealed off from the people around them? There is a certain “push and pull,” between his works as he looks back on this space with a new focus on the activities rather than focusing on one individual’s interaction with books.[15]

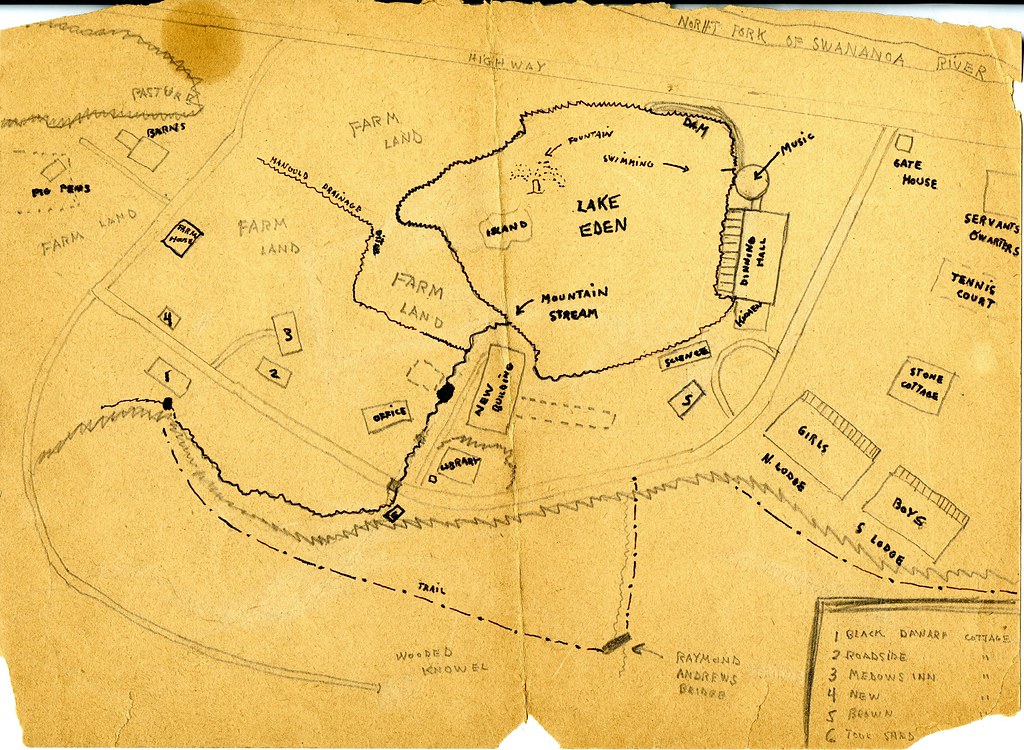

Stop II: Black Mountain College

In the summer of 1946, Jacob Lawrence was offered and accepted a summer teaching position at Black Mountain College, located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of then-racially segregated North Carolina. The school was led by the German Bauhaus teacher Josef Albers, who would come to hold a significant place in Lawrence’s vision of education. The Lawrences traveled by train and remained on campus for the entirety of their eight week stay – Albers suggested that the teaching position would be like a holiday, with only two days a week of required instruction.[16]

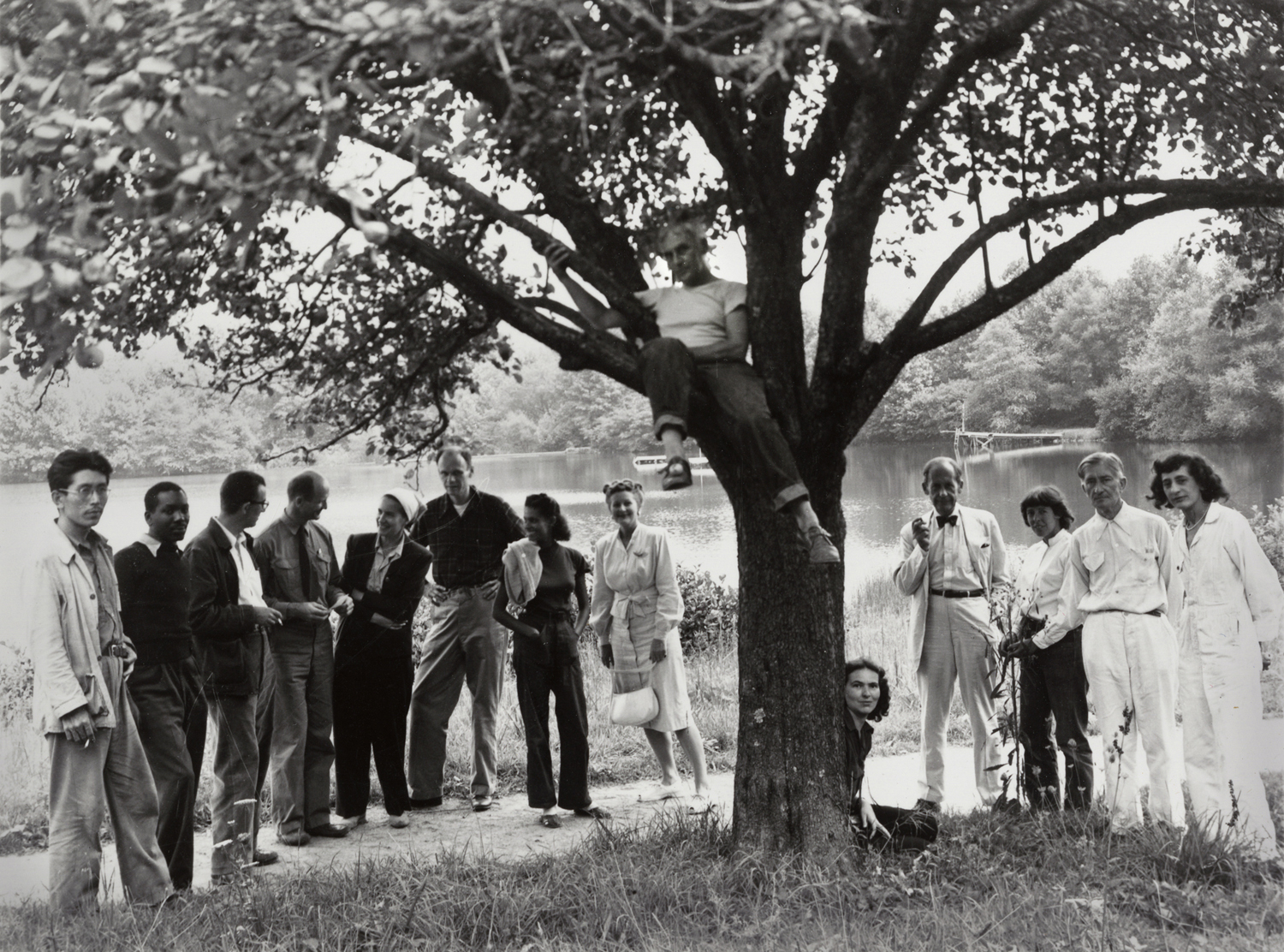

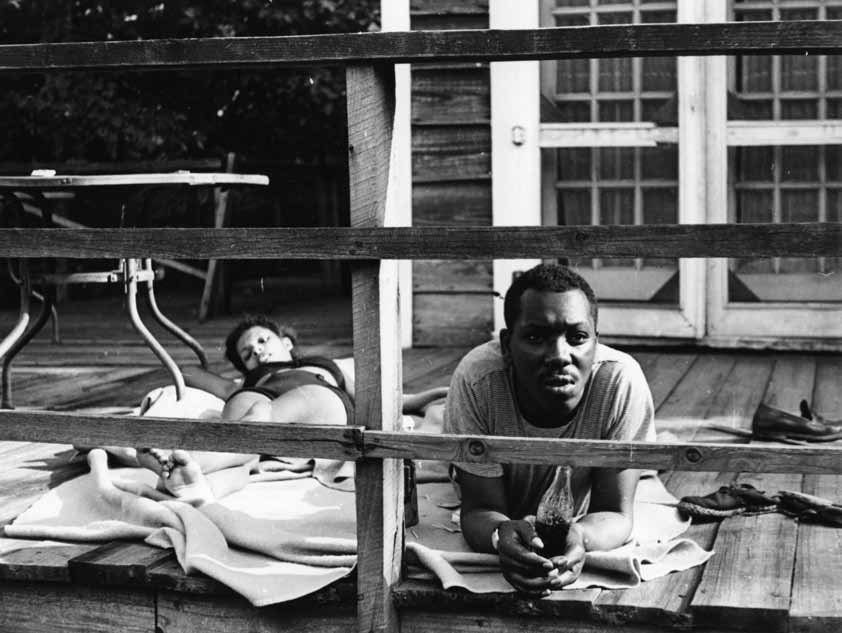

Photographs from that summer show Lawrence and his wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight, posing with the other faculty under a tree in front of the picturesque Lake Eden (fig. 7), or lounging on a deck in the sun (fig. 8).

The relaxed location was directly related to the educational models the college followed, with informal conversations about art and form taking place. The informality blurred the hierarchies between student and teacher, and Lawrence realized that the advantage of Black Mountain College was that they “were all students in a way.”[17]

The school was founded in 1933 with a central aim of teaching the art of living, where art and learning should be synonymous with life.[18] One can imagine why this form of education would appeal to Lawrence with his inclination to integrate his life and his art. The teaching did not stop in the classrooms but was continued over meals in the dining hall. This mingling of teachers and students reflected Lawrence’s early education of mingling with artists and thinkers within the Harlem community. Lawrence found the classes and visual examples provided by Albers fascinating, like when he used a twisted coat hanger to illustrate the importance of line in space.[19] Albers insisted on students beginning with material rather than theory, and he believed that students learned best through experimenting, again echoing Lawrence’s early education. In this regard, he was like Dow and Dewey in his belief that free play develops courage and that through experimentation one can be skillful in constructive thinking.[20]

Participation at the college was intimately tied to sight, and the ability for students to see in the widest sense, to take in the world around them and most importantly to bring awareness to their own “living, being, and doing,” especially for the purpose of art.[21] For instance, Albers’s lessons on color theory involved placing blocks of color in front of each other to illustrate the importance of color and its placement on the picture plane. Lawrence said Albers was so brilliant in his demonstrations he did not need to communicate in clear English, but had a few specific concepts he would use, like ‘push and pull,’ and an emphasis on ‘the picture plane.”[22] These concepts were ones Lawrence frequently referenced in the many interviews he gave throughout his life, and reflected the teaching he received in Harlem, indicating that they reinforced his own philosophy on art making. In Lawrence’s 1978 lecture he spoke repeatedly of Albers, musing appreciatively: “this man was like magic in what he could make you see, how he could open the vision – we look but do we see? The painter is like a magician. You make things appear.”[23] Here, vision refers to the ability to see the plastic (or shapeable) elements within a composition and be able to visually identify only those necessary for the piece to function. In Albers’–and Lawrence’s–philosophy, when one sees the shapes, textures, and colors rather than the objects of representation themselves, one can escape merely copying and being “illustrative.”[24] For Lawrence, every formal choice was an essential part of weaving a composition together, and the forms dictated the content produced.

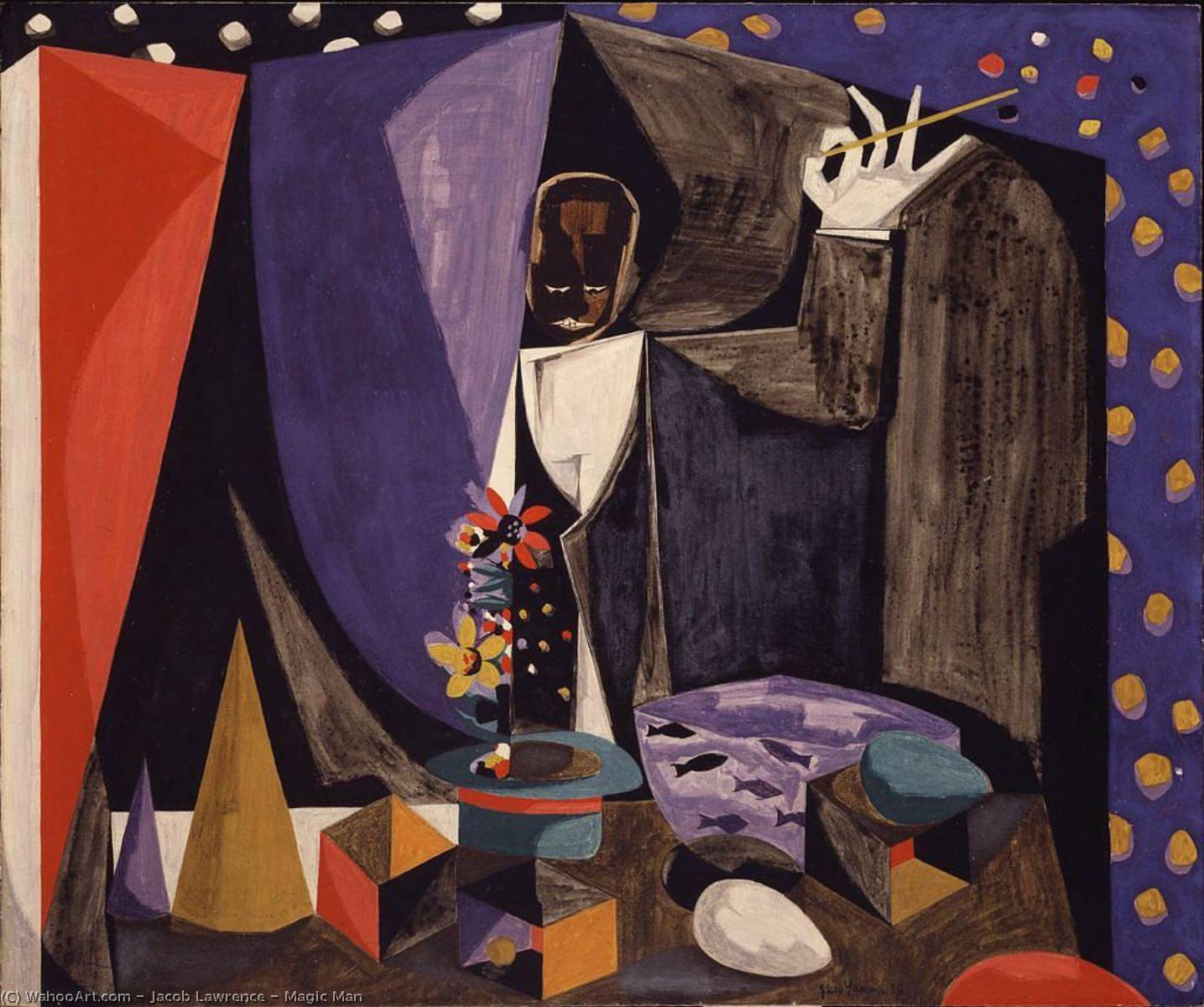

These methods appear in Lawrence’s 1958 painting Magic Man, which plays with colors and inversion in its depiction of a Black magician, making the viewer’s eyes work to understand what is happening in the picture plane (fig. 9). Every element, especially the shadows, lights and colors work to confuse and distract us, as magicians do when they perform their magic tricks. Lawrence has reduced the flowers from the right side down to dots of color, abstracting their forms down to their essential qualities. Lawrence, as the artist, asserts his control over the entirety of the picture plane, and the image is punctuated with areas of pure abstraction, like the dots of color emitting from the wand that encircle the edge of the painting and the planes of red and purple behind the magic man. The dots of color escaping the magician’s wand are the same colors he uses throughout the composition, with the purple fishbowl and yellow flowers. By placing the gloved hand against a black background and making it the size of the head of the magician, Lawrence emphasizes it as the tool by which the magician does his work. Considering Lawrence’s statements about Albers and the magic of the picture plane, the painting can be understood as a meditation on artists and the magic they perform within their work.

Stop III: Seattle, Washington

In 1970 Lawrence traveled west to accept a full-time teaching position in Seattle at the University of Washington, at a time where his life, teaching and career had sharpened his artistic practice and beliefs about experience’s inexorable connection with artistic vision. The University’s offer of a tenured full professorship was a motivating factor, but the move itself to a new location and environment was also attractive and influenced the art Lawrence produced. In 1975 Barbara Miller wrote a “Profile of an Educator” where she discussed Seattle’s characteristic gray atmosphere, and how Lawrence incorporated the graying of color into many of his works like University.[25]Again we see sight implicated with location and experience, and it results in a shifting of artistic practice similar to the complex and abstracted planes of color and forms in his piece Magic Man from after his time at Black Mountain College. In a short essay in the Henry Art Gallery’s 1980 Drawings exhibition catalogue, Lawrence spelled out his belief that experience, sight and living were vital to one’s ability to draw:

Experience, and this largely comes with age, is vital to this kind of response, so I emphasize that – living, seeing. You may walk across campus day in and day out, and then all at once you begin to notice a certain tree that you have been passing all the time: that is the nature of experience. In drawing there is more than just the skill itself, there is also the experience behind it, the feeling, the interpretation: how you see a figure, how you see a tree, how you see anything.[26]

Here Lawrence emphasizes the ways that living, and experience inform an artist’s ability to see directly, which shapes their ability to experience the repetitive processes of their own artistic creation. The skill is not as important as the feeling, the practice, and the repetition of continual experience of life and art are what Lawrence sees as integral to the art making process. Though almost forty years had passed, the influence of Black Mountain College’s sharp focus on sight and living are felt in this passage. In the 1977 interview with Clarence Major, Lawrence discusses “the x factor” that cannot be taught, and I believe he is speaking to a student’s ability to see.[27]

Though “Profile of an Educator” is brief, it offers rich insight into Lawrence’s belief in non-hierarchical learning. It explains how Lawrence saw learning as a two-way street, which is reflective of the oral history between Lawrence and Greene in 1966, where he speaks to teaching as a clarifying force, one that does not end in the classroom, and one that he felt gave his work a “broader dimension.”[28] The impact of Lawrence’s teaching style is evident from his end of term reviews, where he received the highest marks of any professor in the studio section.[29] His colleague Michael Spafford recounted how Lawrence would teach intro level drawing classes in a more advanced, and trusting fashion. He took his introductory level drawing class to the dance department so that students had to think quickly about how to jot down the movements they were seeing. Other professors often waited to introduce movement for more advanced classes.[30] The activity emphasized vision over copying, an important distinction for Lawrence, and revealed his confidence and trust in his students. As Allan Kollar, an MFA student of Lawrence’s put beautifully, “Lawrence always treated you like the person you were going to become rather than the person you were in the present.”[31] The same vision and foresight is apparent in the constructed vision of education within the thin walls of University.

The tangible and intangible tools of education are prominent within the open halls and classrooms of University, wherestudents carry books in the crook of their arms, teachers gesture while speaking and one student carries a compass ruler (fig. 1). The space actively structures and informs the tools of knowledge, from the presence and co-mingling of classes and ideas as well as the active engagement with applied and learned knowledge.[32] The openness of the space dictates the kind of learning that is able to form and take shape, one that is inclusive and in a constant state of change. The University is also site specific, in not only its title but also in the purple and gold school colors and the grays of the chairs and clothes. Location once again influences the vision created. In University a completely purple figure in the foreground walks towards the edge of the painting; they hold books and a curious circle of colorful dots hover between their forefinger and thumb and above their hand. At first when I saw the dots, I thought they were planets, but upon further inspection, and in conversation with Magic Man, I believe they are a painter’s palette hovering in the air. They are the colors that bring the scene to light, the figure once again representing magicians and implicitly the magic work of painters. Lawrence was not necessarily a religious person, but did “believe in something beyond our understanding.”[33] In his 1978 lecture he detailed that painting for him had a great deal to do with what he described as a “search,” but one in which “I don’t know what I am looking for – there’s a certain magic there to go back to Albers words, a certain gestalt that I am looking for. I don’t know if I’ll ever find that.”[34] He strived to create work larger than the sum of its parts and make more out of less – like magic. This purple-clad figure embodies the continuous search; the x factor that cannot be taught. The picture plane contains the magic and mystery that this figure reflects.

A final detail in University is worth noting: in the central background, a teacher leans down to listen to a bespectacled student, who is pointing at himself. This figure looks remarkably similar to the self-portrait in Lawrence’s painting Studio (1978), where he paints a himself bespectacled and turned in profile (fig. 11). The position and glasses are quoted in the figure in the back of University. This intentional quotation reveals that this student is in fact Lawrence, who has placed himself into the role of student, rather than teacher. Throughout his life, Lawrence was a student first and foremost, and was continuously winnowing and focusing on the forms he used. By placing himself in the position of the learner, Lawrence finalizes his image of education: one where ideas flow freely, and there is no hierarchy between mentor and menteé.

I would like to end our journey in the place where we began: Lawrence’s distinguished faculty lecture where he said of his painting University: “I see this every day, how could I not paint it?”[35]Though his tone was light, this paper has stressed the importance of vision and everyday experiences and their relationship to Lawrence’s work. His radical vision of education as an equal exchange between teachers and students, in which learning is a lifelong pursuit, is one we should consider within the broader educational system the United States subscribes to, one of competition, individualism and hierarchies. Lawrence’s philosophy of living and experiencing as a model for art making suggests that art historians, critics and writers should take art classes because doing and participating changes one’s vision. It is also worth noting that at times art historians become so wrapped up in different art movements that they forget to closely look at an artist’s words and visual patterns, at patterns that only become apparent with age. In a broader sense, Lawrence’s philosophy of taking one’s time, of living as art, is one that should be considered within our own lives. Lawrence’s life, work and teaching suggests that magic occurs because of our wandering, seeing, and doing, because we took the time to notice.

- Jacob Lawrence,“I Wonder as I Wander” (3rd Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture, University of Washington, Seattle WA, October 5, 1978). Timestamp, ten minutes. ↵

- Archival letter to Spencer Mosely from box 5 folder 14, page 7. ↵

- Milton W. Brown, “Jacob Lawrence,” 1974, 9. ↵

- Elizabeth Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” in Over the Line: the Art of Jacob Lawrence, 97. ↵

- Carroll Greene, “Oral History Interview with Jacob Lawrence, 1968 October 26.” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Elizabeth Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” 98. ↵

- Turner, 98. ↵

- Margret Halsey Brown, "THE AESTHETIC AND EDUCATIONAL THEORIES OF JOSEF ALBERS." New York University, 1968, 65. ↵

- Turner, 99. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence (University of Washington, 1987): 13, 198.. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” 102. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence,“I Wonder as I Wander,” twelve minutes in. ↵

- National Center of Statistics, “National Assessment of Adult Literacy,” 2003. ↵

- Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” 99. ↵

- Julie Lavine Caro, “Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946,” 2020 in Lines of Influence, 137. ↵

- Ibid., 139. ↵

- Margret Halsey Brown, "THE AESTHETIC AND EDUCATIONAL THEORIES OF JOSEF ALBERS," 56. ↵

- Ibid., 56. ↵

- Ibid., 50. ↵

- Ibid., 60. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence,“I Wonder as I Wander,” 1 hour 11 minutes. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence,“I Wonder as I Wander,” 1 hour 12 minutes. ↵

- Carroll Greene, Oral History Interview with Jacob Lawrence, 1968 October 26. ↵

- Barbara Miller, “Profile of an Educator,” 1975. Box 5, Folder 14, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers, 1816, 1914-2008, bulk 1973-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence et. al., "Faculty Notes,” in Drawing, at the Henry : an Exhibition of Contemporary Drawings by Eighteen West Coast Artists, April 5-May 25, 1980, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington. Seattle: The Gallery. 1980. ↵

- Clarence Major, "Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, The Expressionist." The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977), 17. ↵

- Miller, “Profile of an Educator,” 7. ↵

- Greene, “Oral History.” ↵

- Julie Levin Caro, “The Legacy of Black Mountain College on Lawrence’s Art Pedagogy,” in Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence Black Mountain College, 2019, 80. ↵

- Ibid., 80. ↵

- Henry J. Elam Jr., “Images of Higher Education: Jacob Lawrence’s University,” 37. ↵

- Clarence Major Interview, “Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, the Expressionist,” 19. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence,”I wonder as I wander,” 1 hour and 14 minutes. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, "I Wonder as I Wander," 1 hour 15. ↵