5 A Builder Himself

The Pedagogy and Practice of Jacob Lawrence

Elizabeth Copland

Builders Three (1991) draws us into an intimate scene of two black figures, surrounded by and entwined in a supply of tools, fasteners and wooden planks (fig. 1). The powerful arms of the figures extend beyond a rational reach, emphasizing the potential and strength of these individuals as they collaborate. Six years into his retirement from the University of Washington, Jacob Lawrence made Builders Three during an honorary residency at the Brandywine Workshop’s Offset Institute in Philadelphia, PA. The printmaking residency was one element of his James Van Der Zee Achievement Award, acknowledging a black artist with profound impact.[1] As the award suggested, Lawrence’s impact extended beyond his gifted abilities and important artistic contributions– he was also a notoriously generous teacher who devoted much of his time and energy towards building community and creating arts access for students of all ages. Much like the Utopia Neighborhood Club where Lawrence’s exposure to art began, the Brandywine Workshop aimed to create arts opportunities for predominantly low- and moderate-income Black and Hispanic youth. Selecting ‘builders’ as a theme for this piece was perhaps a symbolic celebration of the team of artists collaborating and teaching at the Brandywine’s Offset Institute, as well as a reflection of Lawrence’s established teaching philosophy and the building of his artistic legacy at this stage of his career.

This paper examines Jacob Lawrence’s Builders Three within the context of the artist’s own educational development, his teaching pedagogy, and his philanthropic investment in supporting the next generation of artists, cultural innovators, and arts supporters. Through an analysis of the formal elements of the print, this paper will argue that Builders Three is a physical representation of Jacob Lawrence’s own educational pedagogy as a builder of progress across many facets including the arts, culture, race relations, and society in general. Let’s consider, when thinking about this depicted scene of two collaborators and the title of the work, Builders Three, that Lawrence was metaphorically making space for the third builder in the conversation of his composition; calling for them to join him in working diligently towards progress.

Prior to his and wife Gwendolyn’s move westward, Lawrence sat on a panel in New York to discuss the state of Black artists in America where he shared, “I don’t know any other ethnic group that has been given so much attention but ultimately forgotten … It’s going to take education— educating the white community to respect and to recognize the intellectual capacity of Black artists.[2] With this in mind, and knowing that Lawrence wanted his work to speak for him, Builders Three begs political, cultural, and metaphorical analysis. While he created many works featuring builders, this work stands out as a depiction of intergenerational learning, specifically Black intergenerational learning and collaboration. In the print, the larger figure on the right stretches across the composition, their arm raised and supporting a board and their legs powerfully active. The second figure, much smaller, appears to be a child, and both figures concentrate on the task at hand. In 1991, when this work was made, Lawrence was balancing his active studio practice and a deep commitment to service. The print therefore can be seen as a microcosm of his own life’s work, since his art was his mode of reaching and educating others on a large scale, and he gave the gift of his time and artistry, generously, to students of all ages.

The theme of builders was a constant subject of interest while Lawrence resided in Seattle. In his analysis of the loosely connected group of works, art historian Peter Nesbett suggests that “Lawrence felt akin to builders, and included himself with carpentry tools in both of his self-portraits of 1977.”[3] Tools decorated his home studio and were a reminder of hope and progress. They may have also been a visual reminder of his roots, as Lawrence’s rigorous studio practice was not his only exposure to physical labor. As a teenager in Harlem, he worked to support his family delivering papers and assisting in a printing shop, and also served in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal jobs program.[4] Lawrence painted what he knew, and his builders were symbolic representations of what he had lived and seen, as well as his desires for the future. Lawrence saw builders, as Nesbett states, as “symbols of hope and persistence, addressing the role and responsibility of all people to the improvement of society.”[5] Lawrence was fortunate to have made artistic connections before and after his service in the CCC that shaped his future, and the figures in Builders Three likely represented the relationships and collaborative spirit involved throughout his artistic development.

The Workbench and Lawrence’s Early Influences

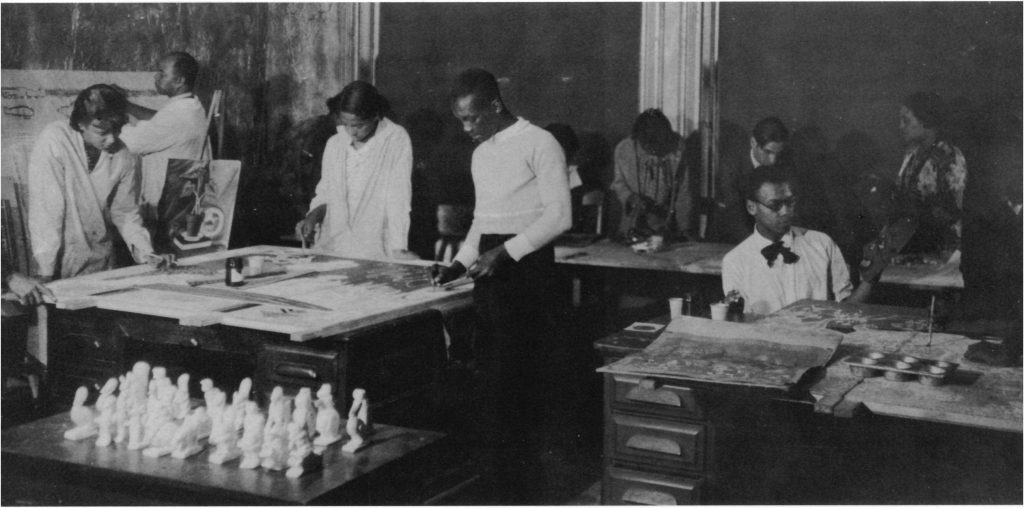

In considering the symbolic elements of Builders Three, the red and brown workbench is littered with tools that are entwined with the arms of the figures and materials in use. Lawrence found tools to be “aesthetically beautiful like sculpture,” as well as representative of man’s potential and symbols of progress and craftsmanship.[6] Tools enable us to build beyond what we can and will do with our own two hands- they extend our capacity and promote our progress. Considering the symbolism that Lawrence appreciated and found in tools, and looking at his development and progression as an artist and educator, there were some key ‘tools’, or powerful forces within his toolkit that shaped the young artist and future educator. These forces included his creative mentors, his environment, and the government supported arts funding that enabled him the time to dedicate to his studio practice. Reflecting on his childhood during an interview, Lawrence shared, “There were three important areas in my life that I can think of. One was coming in contact with the Utopia Center as a child and being exposed to art. The other was Augusta Savage’s seeing that I became a member of the WPA art project.”[7] His formative exposure to Art at the Utopia Center began with experimentation in a wide-range of media including painting, drawing, rug designs, soap carvings and papier mache masks. This experimentation began under the watchful eye of his first artistic mentor, Charles Alston who saw something unusual in young Lawrence. Alston would intentionally offer him the tools he needed, but largely let Lawrence guide himself. This philosophy of learning through doing that Alston encouraged was part of his training at the Columbia Teachers College, where Alston studied under Alfred Wesley Dow.[8] Lawrence was greatly impacted by Dow’s approach to form in his compositions, emphasizing line and harmony, and from the forming of Alston’s caring mentorship. The formative experiences at Utopia Center remained important elements in Lawerence’s artistic and pedagogical tool kit that he continued to draw on throughout his career.

Two additional forces in Lawrence’s development were the government funding that was available for artists and the mentorship that enabled access to that support. In 1933 President Roosevelt was elected and began to develop community support programs to combat the massive impact of the Great Depression. Under this new administration, registered artists could sign up and earn $32 a week for their work under the new Works Progress Administration, which afforded them the ability to continue creative research and affirmed the importance of creative contributions to society.”[9] Lawrence attended the workshop funded by the WPA at 306 West 141st St. where he continued to study with Charles Alston and a whole host of other creatives, including Augusta Savage.[10] Lawrence’s contact with Augusta Savage at the Harlem Community Arts Center (HCAC) was crucial to his success. Savage was an artist-builder herself; she ran her art spaces with an open-door policy stating that any individual that wished to learn about or experience art was welcome and was dedicated to providing arts opportunities for others, in addition to maintaining her own artistic practice.[11] She played a major role in Lawrence’s development and financial security as an artist by her commitment to register him for the Federal Art Project. Lawrence shared, “Thanks to her, I was on the project for 18 months, and it was my first professional work as an artist.”[12] While it only lasted for a short time, the support afforded Lawrence the ability to focus on his craft and broaden his artistic community. In his 1968 interview with Carroll Greene, Lawrence shared on the subject of the FAP, “It was a very informal kind of schooling. You were able to ask questions of people who had more experience than yourself about technical things in painting. They had lectures. They put out books on painting, technical pamphlets and things.”[13] These resources remained in Lawrence’s toolkit throughout his life, and the powerful model of mentorship that he received from Augusta Savage and Charles Alston instilled in Lawrence an inherent value in building up the next generation of artists.

In addition to impactful artistic mentors, another influence in young Lawrence’s development were the public spaces where he came into contact with artwork and resources that documented Black contributions towards American progress. At the Schomburg Library, Lawrence found contextual evidence that supplemented the scenes he wanted to depict, and he also took in free lectures by different members of the Harlem community. It was at the Schomburg library where young Lawrence came into contact and began to learn from “a carpenter-turned-lecturer who made frequent speeches about Black history.“[14] The self-taught historian Charles Seifert —known as ‘Professor Seifert’—played a key role in Jacob Lawrence’s awakening to the importance of African history. Seifert built a successful career in Harlem as a carpenter and contractor, and as he prospered, he amassed a collection of books, manuscripts, maps, and artifacts related to Africa’s cultures and diaspora.”[15] Seifert made history come alive through public lectures and Lawrence in turn took that information and felt inspired to consider his medium to contribute to social change.

Lawrence’s community was filled with artists and teachers of all levels of prestige that welcomed him and made space for his own development and exploration. Considered retrospectively, the impact of all these combined experiences in Lawrence’s life and artistic development, his focus on builders and building in his works that came later carry great metaphorical weight both personally and professionally.

Lawrence’s Compass and Teaching Pedagogy

Situated off the edge of the workbench in Builders Three is the compass tool which is utilized in drawing to create a perfect sphere or arc. In self-portraits, Lawrence often holds a compass himself, confirming its importance in the artist’s mind and a way of conceptualizing his identity. In Builders Three, the use of white for this tool creates a visual that pops out in stark contrast to the dark red surface of the workbench. Its shape creates an arrow pointing from the large figure to the smaller figure. The compass is a tool that both balances the big picture and a focused point, a balance that echoes Lawrence’s arc and legacy as an artist and his focused in the moment mentorship. The informal kind of mentorship that he received growing up in New York offered him powerful models of supportive educators and professional artists. However, Lawrence’s confidence in his own teaching practice was solidified in 1946 during his summer at Black Mountain College. He considered this experience as his initiation into the ranks of becoming a teacher.[16] The invitation from Joseph Albers alone was an acknowledgement for Lawrence that he had tools to share. From his colleagues at Black Mountain College, Lawrence retained “a philosophy of seeing, of having a wonderful appreciation of form and texture and color and value, the abstract elements irregardless of what your style is.”[17] The supportive Dewey-inspired teaching philosophy of learning through doing at Black Mountain College extended the arc of Charles Alston that defined Lawrence’s early years, and the sharing of knowledge across students and faculty was unilateral and of mutual interest and respect.

Jacob Lawrence brought this teaching philosophy with him to the University of Washington in 1971. As many former students and colleagues later reflected, he stood out as a teacher who brought something refreshing and unique to the classroom: a belief in his student’s capacity to dive into complex experimentation within their fundamental courses. He wanted students to feel their way into making art, trusting their intuition. A former student, Laura, “remember[ed] spending the first week in his class with [her] eyes closed, feeling [her] chalk in her fingers and hearing the scratch of the stick on the paper. The exercise taught [her] that art is not something you effect on the outside but find within. It was liberating, washing away the mimicry taught in high-school art classes.”[18] While other colleagues often met their first-year students with the mission of removing bad habits, Lawrence’s approach was additive: he helped students follow their own voices and encouraged them to use their whole selves, what they brought and lived with, to their work. As Lawrence’s student Barbara Earl Thomas shared, “He believed that skill served faith, persistence and vision. If you undertake a work and if you don’t do it with skill, honesty and vision, everyone will know. And it’s just an exercise.”[19] An established artist in her own right, Thomas was shaped greatly by Lawrence’s support and mentorship but maintained her own artistic voice. The stark differences between Lawrence and Thomas’s work, despite their close relationship, is a testament to Lawrence’s ability to develop and support each student’s individual voice.

Lawrence was known for his unique critiquing abilities by students and fellow faculty alike. Artist and UW Colleague Michael Spafford once said that Lawrence “was the only teacher I’ve ever met who could be critical without being negative.”[20] Lawrence’s pedagogy came from a place of curiosity and he found that his conversations with students crystalized his own artistic theories.[21] Lawrence gave his students a conceptual framework to strengthen their practice, and was supportive of their individual interests and subject matter. Judy Night, a former undergraduate student who studied under Lawrence wrote to him “I thought you might enjoy knowing that although I learned a great deal from all of the Professors at the University of Washington, you were by far the most influential, understanding and encouraging teacher that I have ever had the privilege of working with”.[22] Lawrence’s generous and supportive pedagogical approach was undoubtedly shaped by the important mentorship that he found early on from Charles Alston, Augusta Savage and Josef Albers, who cemented the idea in Lawrence that Art was for everyone.

Service and Community Building

Just as Augusta Savage was a pillar in her community, dedicated to providing art programming for all, Lawrence was similarly committed to service, particularly in his later years. Ellen Harkins Wheat, herself a former student of Lawrence as well as one of his first biographers, noted of his contributions: “His active participation in the academic community has helped to build arts programs (he served six-year terms on both the Washington State Arts Council and the National Council of the Arts), efforts that might be seen as his desire to propagate the kinds of opportunities that served him so well early in his career.”[23]

Lawrence was aware that government opportunities that helped launch his career were still necessary decades later, particularly for students in lower income areas. The state of arts education in Washington State shifted significantly during the 90’s towards an emphasis on standardization, which forced administrators to reallocate funding towards other subjects and push the arts to the back-burner. A report entitled, “The Support Infrastructure for Youth Arts Learning”, examines the shift of Arts education in the US between 1984 and 2000. Pressures for accountability in non-arts subject areas and decreases in districts’ discretionary budgets created hostile conditions for sustained arts education. It is largely left up to school districts to raise funds and establish programs to provide their students with quality arts opportunities. As many schools rely on arts grants, state-funded public art collections have become a powerful means of early arts exposure for children. The Art in Public Places Program in Washington state has a

process for K-12 Schools to apply for an artwork from the state collection to be placed in their care, on display for students and teachers to utilize and enjoy. There is an emphasis on selecting works that provide curricular connections, and for School communities to use the artwork as a jumping off point to explore other disciplines.[24] Jacob Lawrence has 39 pieces of art in the Washington State Public Art Collection, 38 of which are housed in public schools. This collection includes several works on his ‘builders’ theme including, The Builders (1974), Tools (1977) and Carpenters (1977) [Fig.4], and Builders Three (1991) [Fig.1]. Through his consistent use of a bold color palette, scenes of progress, and his celebration of the artistry of simple hand tools, these works offer something for every viewer; a potent reminder that anyone of any age can be a contributor.

The dissemination of Jacob Lawrence’s work, particularly in K-12 schools, had an enormous impact on the next generation. He received hundreds of personal letters, drawings and photographs from students of all ages, wanting to know more about him as an artist and person, or just wanting Lawrence to know how much his work meant to them. For instance, 6th grader Markia Williams shared:, “I am writing because I think you are a splendid artist and I just thought you should know it… I just wanted you to know that there is someone who admires you and your work. Please write back.”[25] Lawrence visited schools and offered phone interviews to respond to student questions.[26] Another young fan, Dawniah Eddy, from Silver Lake Elementary in Washington State wrote “In my class at school we have been studying your work. I really love your work. You use beautiful colors that catch your eye real quick. I especially like your picture of the runners with torches. I like the way you brought out the muscles in their legs. We wanted to know if you could stop off at our school sometime. We think it would be great.”[27]

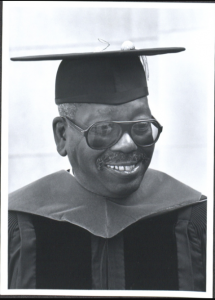

Shortly after his retirement from the University, Lawrence was commissioned to create a massive 41ft mural in Meany Hall. He quoted a fee of only $25,000, an amount that would barely cover materials and overhead. “It wasn’t quite a gift, but I took into consideration that it was for the university,” he explained at the dedication ceremony.’[28] In Lawrence’s mind, the initial output of such a gift came back to him, much as he saw his teaching practice. He and his wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, supported numerous projects at the UW beyond the gift of their works, including undergraduate and graduate student scholarships, financial support for the development of a printed MFA Thesis Exhibition Catalog, and an endowment that provided student scholarships. In 1993, the UW School of Art officially named the gallery after Jacob Lawrence. Director of the School at the time, Jerome Silbergeld, shared, “Your art, your humane values, and your years of service to the School of Art have been a great inspiration for all of those who know you and your work, and we are lucky to count you as one of us.”[29] This space remains a catalyst for creative conversation and a platform for sharing work today.[30]

Builders Three celebrates the importance of sharing one’s own craft, and the idea that legacy cannot be built alone. Lawrence’s own work as a builder of progress, honed over the course of a 60-year career, provided the foundations to recognize the power of collective labor in any field and the capacity for human potential towards progress. Of the many works that he created on the builders theme, Builders Three uniquely showcases an educational exchange and scene of collaboration that ties into Lawrence’s own philosophy on reciprocal knowledge. He stated on numerous occasions how vital his teaching practice was to him in solidifying his own studio practice. As his former student and friend, Barbara Earl Thomas, shared about her time with Lawrence as an instructor. “He really looked at your work and tried to figure out what it was you were trying to do,” Thomas says, “then he tried to help you do that.”[31] Lawrence’s pedagogy was centered on meeting students where they were at in their development, and helping them find their own way ahead, just as Augusta Savage and Charles Alston had encouraged him to do.

Lawrence’s builders act as important visual reminders of this work, our collective potential and an invitation to explore art, in addition to being symbols of how Lawrence lived his life. He once said, “For me a painting should have three things: universality, clarity, and strength. Universality so that it may be understood by all men. Clarity and strength so that it may be aesthetically good. It is necessary in creating a painting to find out as much as possible about one’s subject, thereby freeing oneself from having to strive for a superficial depth.”[32] Like the central figure depicted in Builders Three, Lawrence was powerful in his purpose, firmly following his own artistic voice, while also contributing towards the growth of others. The fruits of Lawrence’s labor in Washington state continue to unfold even twenty years after his passing- gifts for future generations who can look to his legacy for inspiration to move us forward, the way Lawrence would have wanted; laboring, creating, and standing strong in togetherness.

- “Our History.” Brandywine Workshop and Archives, 2019 ↵

- Bearden, Romare, et al. "The Black Artist in America: A Symposium." ↵

- Nesbett, Peter T. "Jacob Lawrence: The Builders Paintings," Jacob Lawrence : the Builders, recent paintings (1998). PG.18 ↵

- Yoes, Sean. “Jacob Lawrence: Eyes of the Harlem Renaissance.” Afro News: Black Media Authority. February 18th, 2021. https://afro.com/jacob-lawrence-eyes-of-the-harlem-renaissance/ (accessed June 7, 2021). ↵

- Nesbett, Peter T. "Jacob Lawrence: The Builders Paintings," Jacob Lawrence : the Builders, recent paintings (1998). PG.6 ↵

- Sims, Lowery Stokes, "The Structure of the Narrative: Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence's Builder's Paintings, 1946-1998." In Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, edited by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois 97-109. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2000. PG.206 ↵

- Stewart, Marta Reid. "Women in the Works: A Psychobiographical Interpretation of Jacob Lawrence’s Portrayal of Women as Icons of Black Modernism” Source: Notes in the History of Art 24, no. 4 (2005): 56-66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23207950. PG. 57 ↵

- Hills, Patricia., Lawrence, Jacob, and Getty Foundation. Painting Harlem Modern : The Art of Jacob Lawrence. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009. PG.13 ↵

- Wheat, Ellen Harkins., Lawrence, Jacob, Hills, Patricia, and Seattle Art Museum, Issuing Body. “At Home in the West”. Jacob Lawrence, American Painter. Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1986. 29 ↵

- Turner, Elizabeth Hutton "The Education of Jacob Lawrence." In Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, edited by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois 97-109. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2000.PG.97 ↵

- "Jacob Lawrence." St. James Guide to Black Artists, 1997, St. James Guide to Black Artists, 1997-01-01, PG 471. ↵

- OLIVER, STEPHANIE STOKES. "JACOB LAWRENCEA MASTER IN OUR MIDST." THE SEATTLE TIMES, October 27, 1985: 14. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/0EB53183DE103022.. ↵

- "Oral History Interview with Jacob Lawrence" by Carroll Green, October 26, 1968. Lines of Influence, SCAD Museum of Art. 2020. ↵

- Gasman, Marybeth., and Sedgwick, Katherine V. “A Gift of Art; Jacob Lawrence as a Philanthropist”. Uplifting a People : African American Philanthropy and Education. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. 175-188 ↵

- https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2015/onewayticket/key-figures/charles-seifert/ ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob, Rensburg, Storm Janse Van, Levin Caro, Julie, Greene, Carroll, Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, Publisher, and SCAD Museum of Art, Issuing Body, Publisher, Organizer, Host Institution. Jacob Lawrence : Lines of Influence. Zurich, Switzerland : Savannah, Georgia: Scheidegger & Spiess ; SCAD Museum of Art, 2020. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob, Rensburg, Storm Janse Van, Levin Caro, Julie, Greene, Carroll, Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, Publisher, and SCAD Museum of Art, Issuing Body, Publisher, Organizer, Host Institution. Jacob Lawrence : Lines of Influence. Zurich, Switzerland : Savannah, Georgia: Scheidegger & Spiess ; SCAD Museum of Art, 2020.PG.133 ↵

- Cronin, Mary Elizabeth. "Finding Common Thread in an Uncommon Canvas; Jacob Lawrence's Moving Images Open Windows to Heritage." The Seattle Times, December 22, 1993: E1. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view? p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/0EB536E7A6FBDEB3. ↵

- Tu, Janet I.. "Mourners say farewell to artist who `was gifted and a gift to us'." Seattle Times, The (WA), July 13, 2000: B1. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view? p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/0EB53A68BAD4FD8F. ↵

- Tu, Janet I.. "Mourners say farewell to artist who `was gifted and a gift to us'." Seattle Times, The (WA), July 13, 2000: B1. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view? p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/0EB53A68BAD4FD8F. ↵

- Caro, Julie Levin, “Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946”. In Jacob Lawrence, Lines of Influence. Exh. Cat. Savannah, GA: SCAD Museum of Art. PG. 142 ↵

- Judy Knight to Jacob Lawrence, Box #5, Folder #15, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers, 1816, 1914-2008, bulk 1973-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution ↵

- Wheat, Ellen Harkins., Lawrence, Jacob, Hills, Patricia, and Seattle Art Museum, Issuing Body. “At Home in the West”. Jacob Lawrence, American Painter. Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1986. PG. 191 ↵

- https://www.arts.wa.gov/public-art/ ↵

- Markia Williams to Jacob Lawrence, Box #4, Folder #40, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers ↵

- Cathy Bean to Jacob Lawrence, Box #4, Folder #39, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers. Cathy Bean, an Art docent volunteer at Frank Love Elementary, sent a note, “Thank you for taking the time to talk to our 6th graders over the telephone... The students and I were very impressed that a person of such great accomplishments would take time to answer our questions. It was one of the highlights of my 11 years of being a PTA art docent. ↵

- Dawniah Eddy to Jacob Lawrence, Box #4, Folder #25, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers ↵

- Oliver, Stephanie Stokes. "Jacob Lawrence, A Master in our Midst." The Seattle Times, October 27, 1985: 14. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view? p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/0EB53183DE103022. ↵

- Jerome Silbergeld to Jacob Lawrence, Box #5, Folder #15 ↵

- The Jacob Lawrence Gallery presents 12 exhibitions each year, eight of which feature student work. In addition to these exhibition opportunities, the gallery hosts an internship program where students learn curatorial methodologies, exhibition design and production, and act as docents for the exhibitions on view. There is an annual Jacob Lawrence Residency in the Gallery, which invites Black artists at all stages of their careers to have a residency during the month of January to develop new work and an exhibition during the month of February, Black History Month. Additionally, the Jacob Lawrence Gallery is the site of the The Black Embodiments Studio (BES), an arts writing residency and a public lecture series dedicated to developing complex, creative, and rigorous discourse around contemporary black art and artists. ↵

- Barbara Earl Thomas is an established artist in her own right. Her exhibition, The Geography of Innocence, was recently on display in the Seattle Art Museum. https://thomas.site.seattleartmuseum.org/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw2tCGBhCLARIsABJGmZ4Bv3hUgJvSHll0Y9yIQNmDBVrp1bA0iQnr9GtXDBGi1v-bpqE3HXAaAuaFEALw_wcB ↵

- Wheat, Ellen Harkins., Lawrence, Jacob, Hills, Patricia, and Seattle Art Museum, Issuing Body. “At Home in the West”. Jacob Lawrence, American Painter. Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1986. 29 ↵