12 Provisional Humanism

Jacob Lawrence’s Engagement with the Philosophy of Humanity

Samantha Seaver

Abstract

Artist Jacob Lawrence has been dependably analyzed through cultural and historical perspectives rather than the psychological and philosophical lenses utilized to describe other artists of the time. Scholars tend to focus on the first three decades of his life, concentrating on how he was a child prodigy and involved in the Harlem renaissance, but leaving the works from the majority of his career (spent in Brooklyn and Seattle) neglected. The emotional complexity present in his art demands to be looked at with similarly intricate theories and outlooks.

This essay will explore the philosophical theory of humanism and how it applies to Lawrence’s art, focusing on his 1983 Hiroshima series, eight paintings that Lawrence created to accompany a reissue of John Hersey’s 1946 book with the same name. While the series is often described as an outlier, it may instead be a more explicit example of themes and thoughts Lawrence engaged in and depicted in both earlier and later works. I will be arguing that Lawrence expressed a blend of both religious and secular humanism throughout his career and that the Hiroshima series is a special example of provisional humanism, an exploration into how humans can lose their humanity. This is shown through Lawrence echoing a similar metaphorical approach to Hersey’s, his inclusion of depersonalized and universal imagery, and focusing on everyday rituals that are neither explicitly religious nor definitively secular.

Jacob Lawrence’s work has been consistently analyzed through cultural and historical perspectives rather than the psychological and philosophical lenses ascribed to other modern art. When one is a minority in America and reaches levels of accomplishment usually only available to the majority, those watching can become blind to anything but the person’s biography, oftentimes viewing them as less of an individual and as more of a spokesperson for their entire community/culture. Writings on Lawrence’s life almost always focus on his childhood, how he was a child prodigy and involved in the Harlem renaissance, then take this upbringing and wield it as a lens through which to view the rest of his career. The other main thread of analysis is likewise reductive, focusing on Lawrence’s place in modernism but often straining to fit him into pre-established categories and genres of the time period. In recognition of this persistent dynamic, Peter Nesbett, who co-led the Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, challenges those interested in researching Lawrence to situate his works “within theoretical contexts that free it from narrow, historical accounts of ‘the modern’ and modernism”—a call to which this essay responds.[1]

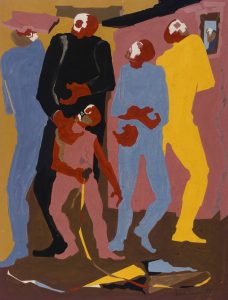

While Lawrence is consistently compared to artists like social realist Ben Shahn and cubist Picasso, it feels as though many of his works, which can be read through lenses other than “modernist,” are neglected. There are a variety of reasons why Lawrence’s works have not received the same level of analysis as other art of the same time. Critics and viewers of Lawrence have been hard-pressed to fit him into a pre-established genre or theoretical movement. A large part of this is that he did not have his own Pocket Art Critic, in the way that Pollock had Greenberg, Cézanne had Fry, and de Kooning had Rosenberg (to name a few of many). This is not to say that Lawrence had no supporters or scholars on his side, but he did not have an established art critic showing him off as a prime example of some cerebral and experimental new art movement. We need to start recognizing in his oeuvre the same psychological and philosophical complexity that critics and scholars seem to require to analyze a work beyond visual and biographical appraisal. This essay will take the lead in that charge by exploring the philosophical theory of humanism and how it applies to Lawrence’s art, focusing on his 1983 Hiroshima series (both cerebral and experimental) as the most explicit example of humanism and demonstrating that it did not diverge as severely from his oeuvre as has been popular thought (fig. 1). I will argue that Lawrence engaged in both religious and secular humanism throughout his entire career and that focusing too heavily on historical context can occlude us from his psychological intensity.

Philosophical humanism is one of the messiest and most highly debated stances of the 20th century. Humanists have existed long before the 1900s, but in 1945, philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre gave a lecture in Paris in a valiant effort to not define it, but help thinkers feel alright with its uncertain definitions. Sartre argued that that humanism has two very different meanings. The first was a belief system designed to uphold man as the “supreme value,” aka the concept of man as the measure of all things—an example is the notion that humans are above animals because animals are slaves to their appetites and we are slaves to something above earthly affairs. There are understandable religious connotations here.[2] Religious humanism today is common in the United States and entails centering congregational activities and practices on individuals’ needs, desires, and happiness. During Lawrence’s involvement in the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, he may have been exposed to this kind of thinking.[3] The second meaning, according to Sartre, is that there is no legislator of man but himself; “that he himself, thus abandoned, must decide for himself.”[4] This, known as secular humanism, is equivocally atheistic—the claim centers human as not only above other beings, but also as in control of and responsible for themselves. Many thinkers believe that secular humanism bottoms out at religion anyway, but that is for a different essay.

Many of writers have labeled Lawrence a humanist, but seem to employ the term only as an explanation for why Lawrence paints about issues beyond race. When historian Paul Karlstrom touches on the Hiroshima series, he writes, “While grounded in Harlem and black heritage, Lawrence here declares his independence from group—and indeed from community—and his participation in the broader humanist discourse.”[5] For scale, throwing out the label of “humanist” is as complex and rich in potential discussion as casually mentioning that Lawrence was a Marxist and then not elaborating on what humanism actually is or how potent a lens it is through which to view his art. Due to the undefined and uncertainty of humanism, there have been generalized applications of the term “humanist,” such as Karlstrom’s, that differ from employing the term “philosophical humanist,” a label that denotes more theoretically involved invocations. Lawrence’s position as a philosophical humanist extends beyond the conceptually emptied meaning of “humanist” and acknowledging this will allow us to see the different techniques that reflect his theoretical complexity.

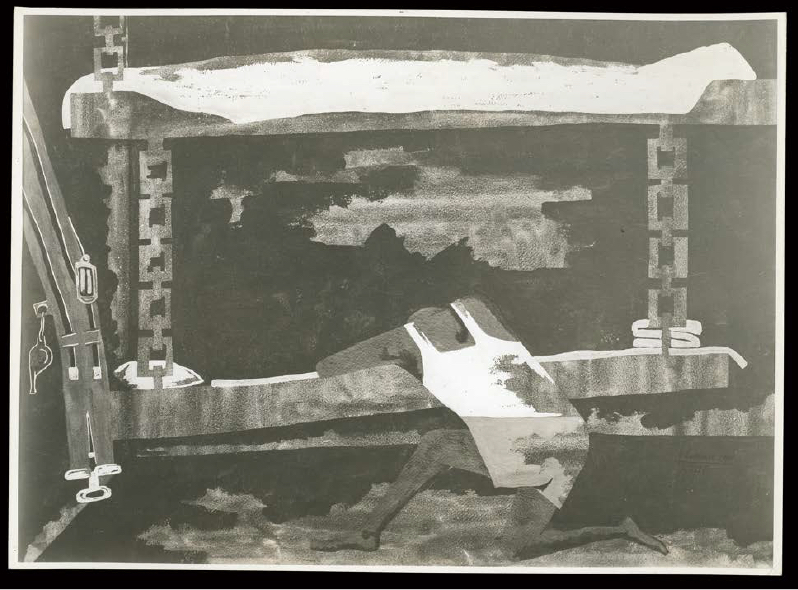

Much of the evidence for Lawrence’s humanism seems to stem from his focus on human subjects in most of his works. However, philosophical humanism extends beyond simply acknowledging humans. One can see Lawrence employing philosophical humanism in how he addresses religion. In a 1944 interview, Lawrence identified Prayer (figure 2), which portrays a figure on his knees in prayer, leaning heavily on his bunk at sea, as his favorite work of the Coast Guard Series.[6]

Interviewer Aline Louchheim describes the work as a “completely subjective painting,” depicting a “vastness, not only of the sea, but of the universe, and in the solitary figure in his moment of intense privacy,” in which Lawrence had “captured the loneliness of the ship on the sea and of man seeking contact with God.”[7] Centering a religious scene around one person’s immediate needs, as shown through the loneliness of being at sea and hinting at a greater psychological or spiritual struggle, is a technique used in a philosophically-grounded religious humanism. Using a man as the measure here, Lawrence zooms in on his situation while what he actually evokes is something much larger. This generalizability or relatability as shown through an individual or small group is a trend in Lawrence’s art, and one of his primary goals as an artist. Shortly before his death, Lawrence reflected on this conviction, stating that, “For me a painting should have three things: universality, clarity and strength…. It is necessary in creating a painting to find out as much as possible about one’s subject, thereby freeing oneself of having to strive for a superficial depth.”[8] Here, Lawrence articulates that one must go vertically into a subject’s experience rather than horizontally, just scratching the surface of a concept.

Lawrence found someone who approached social commentary in a similar way in journalist and author John Hersey. Lawrence was in the last two decades of his career when Sidney Schiff, president of the Limited Editions Club reached out to him to choose any book he wanted for a special edition publication.[9]

Lawrence chose to illustrate their 1983 edition of journalist Hersey’s Hiroshima, first published as an article in the New Yorker in 1946 (fig. 1).[10] Hersey wrote about the lives of six survivors of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, starting at the morning of the bomb and following them through the days immediately surrounding the event, ending a few months after. Perhaps Lawrence was drawn to Hersey’s own experimental style of art; Hersey was a pioneer of “New Journalism”—a writing style that borrowed fictional writing techniques, highlighting a subjective perspective and emphasizing “truth” over “facts.”[11] In other words, New Journalists used man as the measure—elevating a person or group of people’s subjective experience to a place of evidence, resulting in a piece of journalism positioned around this human-centered way of knowing. This seems remarkably similar to Lawrence’s approach to art. Hersey zoomed in on six survivors to comment on the brutality of a global war and the dangerous inhumanity of technological advancements; likewise, Lawrence zoomed in on thirty panels to comment on the entire history of America’s founding (Struggle series, 1954-56).

His approach to painting history has always focused on highlighting individuals, as seen in the Struggle series, where most of his panels depict a handful of people even if the event is as large as a civil war, such as in Panel 13, Victory and Defeat (figure 3). This is revisited in both men’s approaches to Hiroshima, both men break down the whole into its respective parts, then go even further—focusing on how individuals’ experiences can speak to larger issues, paying attention to subjective “truths” over surface-level facts.

Hills writes that Lawrence “attempted not to illustrate Hersey’s account but rather to evoke the horror in metaphoric visual terms.”[12] While terms like “metaphoric” demonstrate the conceptual nature of Lawrence’s works, we may better understand the intention behind his techniques through the artistic and literary devices of “synecdoche,” using the name of one thing to represent something related. Hersey uses these devices as well, as the meaning of his work was not in only these six survivors’ tales, but in what they stood for—six stories representing the whole event and each one consisting of identifiable details that one can relate to their own experience. When introducing one of the six, Dr. Masakazu Fuji, he writes that on the morning of the bomb, “He ate breakfast and then, because the morning was already hot, undressed down to his underwear and went out on the porch to read the paper.”[13] The simple universality of his experience is not limited to Dr. Fuji’s experience. That morning, everyone all around the world ate their breakfast, including the people in the sky and the people down below. This is combined with the vulnerability of Dr. Fuji. He, like others that Hersey included, was in his underwear when the bomb struck. This aggressively human thing of wearing underwear, something that sets us apart from all other animals, speaks to the larger human condition.

Lawrence approached his illustrations in a similar way. He created eight paintings to accompany Hersey’s book, each one consisting of synecdoche to create grander implications. In his artist statement, Lawrence writes that “Because this book is such a strong statement of man’s inhumanity to man, I found this work to be a most challenging book to illustrate.”[14] Here we see Lawrence’s interest in “provisional” humanism—he is concerned with how we can lose our humanity towards one another and finds it to be a challenge, but one that he has volunteered to take on. Provisional humanism is a subset of philosophical humanism that explores how humanism is not the same as optimism.[15] Provisional humanism rose to the philosophical forefront during WWII as a way to explore concepts like Hiroshima and Nazi concentration camps, investigating how humans can lose their humanity, because they obviously can, and that just because humanism puts humans at the center of the discussion does not mean they are without fault.[16] Lawrence engages in this exploration here, writing,

“In my attempt to meet the challenge, I read and reread this work several times and, in doing so, I began to see great devastation in the twisted and mutilated bodies of humans, birds, fishes and all of the other animals and living things that inherit our earth. The flora and the fauna and the land that was at one time alive, was now seared, mangled, deformed, and devoid of life.”[17]

This imagery is seen in his paintings—while they all center human figures as the focal points, he depicts dead birds and fish as well.

His Man with Birds (figure 4) is particularly exemplary of his artist statement. While the man appears to be another victim of the bomb, as the style in which Lawrence painted him does not differ from the other subjects, he also appears to be quite literally twisting and mutilating the crows’ bodies. This reads as a metaphor for how man is not guiltless—it is us inflicting the pain on ourselves, a humanist struggle, one inseparable from our concept of humanity. The man, bloodied and skeletal, is also active in another being’s suffering. There is no accusation or assignment of responsibility here, simply an acknowledgement of the vicious cycle of “man’s inhumanity to man.”[18]

In a perfect blend of religious and secular philosophical humanism, Lawrence asks in his artist statement,

“What have we accomplished over these many centuries? We have produced great geniuses in music, the sciences, the arts, dance, literature, architecture and oratory among many other disciplines. And we have in the meantime, developed the means to destroy in a most horrible manner, that life that is our God-given right.”[19]

He questions how men are capable of doing what they do when they are also capable of such beauty. He says that life is God-given, yet that it is also a right, hinting that while humans are still under the influence of God, they also have a rightful duty or responsibility to one another, not only to the powers that be. Historian Tania Tribe eloquently explains the religious connotations of the series, noting “a subtle secular eschatological tension… forcing himself to ‘think the unthinkable’: the possibility of a real end to the world, an end now made possible by humans themselves.”[20] She claims that the series deals with eschatology, the aspects of theology concerned with death and final judgments, but that what Lawrence is finding is that there is no God creating the end of the world here. It is humans.

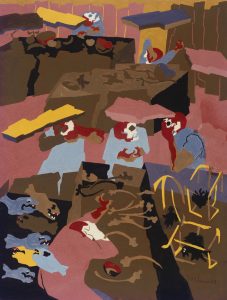

Family (figure 5) from the series perhaps demonstrates this best. In it, a family sits around a table, perhaps sitting down to a breakfast like in Hersey’s accounts. Their faces are turned up to the sky and their skin is already flayed, demonstrating, along with the dead crow on the windowsill, that the scene takes place in the moments of that “noiseless flash” that Hersey reiterates as a common memory of the bomb. What is particularly interesting here is that their arms are all on the table and their palms are upturned, outstretched to one another, as if they were just about to, or in the middle of saying grace. Their chain of hands was interrupted, breaking their prayer, and suggesting that there is a human interference with God’s plan occurring. Here is that secular-religious tension, one that Hersey engages in as well, as he includes much discussion of religion. In Hersey’s text, one of the six survivors is German priest Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge and another is Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, pastor of the Hiroshima Methodist Church. Six months after the bomb, Father Kleinsorge visits a survivor in the hospital. She asks him, “If your God is so good and kind, how can he let people suffer like this?” and makes a gesture that Hersey describes as toward her injuries, the hospital room, and “Hiroshima as a whole,” another example of synecdoche—one patient’s injuries represent the hospital room, which also stands for the entire city, which is now a reflection of the entire world [21] Hersey appears to take a provisionally humanist, or at least more skeptical stance to Father Kleinsorge’s response, writing, “He went on to explain all the reasons for everything” and ending the chapter there.[22]

Like Hersey, Lawrence does not elaborate on or represent the reasons for anything in the series other than each other. He says that he wanted to “get the feeling of this tremendous tragedy in a very symbolic way. There are a lot of symbols in the works. I use a drooping flower and broken trees—things that are in the process of dying: moribund.”[23] His use of universal symbols and synecdoche allows the viewer to feel connected to the figures and the situation, so connected that one may even feel, in a small way, responsible. A small child flying a kite, such as in Boy with Kite (figure 6) commonly evokes feelings of life and hope. [24]The belly-up crows are a recurring symbol throughout the series, standing for the death of many beings.

The marketplace in Market (figure 7) is something any viewer can put themselves inside. The busy stands where one runs into neighbors and meets strangers, the fish, the meat. Yet here the fish bare gruesome, deathly faces and the conversation partners are skeletal, bleeding, and grabbing at their skin—at once the same on the inside and completely split apart. Marketplaces are locations that provide the most human contact people may have all week. Going to the market is usually a social event, one that ties people from a community together over a necessity—food. Lawrence’s inclusion of this scene as one of the eight is poignantly symbolic of the importance of community, perhaps on an international scale, and how if every culture in the world has a marketplace in common, then why is this not enough to bond us. He uses the synecdoche of a small section of a marketplace to speak to this entire human experience. The universal cultural imagery differs from Hersey’s highly-detailed account that places the reader in Hiroshima, but only releases his synecdoches and universal symbols from a cultural binding, creating a larger, international scope of effect. Lawrence said this was intentional, telling Ellen Harkins Wheat the year after the commission, “I used my own experience…I don’t think I could have executed the Japanese [features], and I don’t think it was important either. I didn’t want it to be an illustration of that sort; I wanted it to be one in terms of man’s inhumanity to man—a universal kind of statement.”[25] Here Lawrence directly connects his series to provisional humanism, indicating a concern that he has addressed over many decades, but never so literally as in the Hiroshima series.

Taking a bird’s eye view of Lawrence’s career, one can see a diverse array of paintings used to convey complete philosophies. What Lawrence continues to revisit is this provisional humanism—a call to action for fellow humans to take control of their lives and the lives of others, to notice how connected we all are, to reflect on the damage we have done. The religiosity in Hiroshima is not to send a message that this is all part of God’s plan, but to say the opposite: we are interfering with something sacred, with our God-given life, and we must take responsibility.

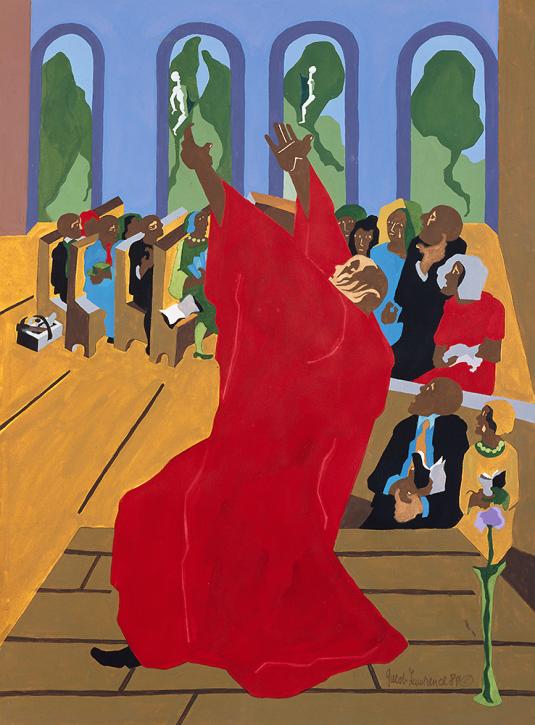

The shaky, flimsy quality of the Hiroshima series is seen again in his Eight Studies for the Book of Genesis (1989), where he used silkscreen prints to remember his time growing up in the Abyssinian Baptist Church and watching preachers deliver their sermons. It is interesting that the title recalls the Book of Genesis, yet the focus is once again on the commonplace experience of going to church, rather than the spiritual and supernatural experiences detailed in the actual bible. His focus is always on humans—on their lives, their experiences, and their “truths.” The Hiroshima series is where he does this most overtly, but this approach can be seen in his career-wide engagement with religion, race, labor, and truly any of his scenes including human subjects. In an interview with Avis Berman, Lawrence says that he took the Hiroshima commission “because I wanted to contribute something that will stand against this whole terrible course of human destruction.”[26] Through synecdoche, universality of symbols and imagery, relatability of content, and a questioning of humanity and inhumanity, Lawrence helps the viewer to feel connected to the situation and each other—so connected that one may even feel, in a small way, responsible. Perhaps this is how we preserve our humanity.

- Peter Nesbett, American Masterworks from the Merrill C. Berman Collection (New York: Alexandre Gallery, 2015), Exhibition catalogue, 40. ↵

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “Existentialism is a Humanism” (lecture, Club Maintenant, Paris, October 29, 1945). ↵

- “Jacob Lawrence: Eight Studies for the Book of Genesis,” Henry Art Gallery, accessed May 29, 2021. https://henryart.org/exhibitions/jacob-lawrence. ↵

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “Existentialism is a Humanism” (lecture, Club Maintenant, Paris, October 29, 1945). ↵

- Paul J. Karlstrom, “Jacob Lawrence: Modernism, Race, Community,” in Over the Line: the Art of Jacob Lawrence, ed. by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2001), 242. ↵

- Aline B. Louchheim, “Lawrence: Quiet Spokesman,” ARTnews, October 15, 1944, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/jacob-lawrence-interview-1944-1202676195/. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 133. ↵

- Sidney Schiff to Jacob Lawrence, April 14 1981, Box 23, Folder 31, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers, 1816, 1914-2008, bulk 1973-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” The New Yorker, August 31, 1946. ↵

- Nicholas Lemann, “John Hersey and the Art of Fact,” The New Yorker, April 22, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/04/29/john-hersey-and-the-art-of-fact. ↵

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 255. ↵

- John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” The New Yorker, August 31, 1946. ↵

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 255. ↵

- Richard Norman, On Humanism (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), 20. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 255. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” PhD diss., (University of Washington, 1987), 36. ↵

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: the Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 255. ↵

- Tania Costa Tribe, “Slavery to Hiroshima and beyond: African-American Art and the Apocalypse,” Word & Image 29, no. 3 (July 1, 2013) https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2013.822146. ↵

- John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” The New Yorker, August 31, 1946. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” PhD diss., (University of Washington, 1987), 36. ↵

- Tania Costa Tribe, “Slavery to Hiroshima and beyond: African-American Art and the Apocalypse,” Word & Image 29, no. 3 (July 1, 2013) https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2013.822146. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter (Seattle: University of Washington Press in association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1994), 154. ↵

- Avis Berman, “Jacob Lawrence and the Making of Americans,” ARTnews 83 (1984): 86. ↵