14 From Mask to Collage

Lawrence's 1977 Self-Portrait

Monica Ionescu

Abstract

Jacob Lawrence created this self-portrait to be presented with his induction into the National Academy in December 1977. Almost instantly, critics and art historians analyzed this work as “elusive” and “mask-like” due to the block colors that form his face and the artist’s race.[1] While this statement may hold some truth, Lawrence’s race has been either explicitly or implicitly tied to what he creates. Critics have also described Lawrence’s work as childlike or simple, un-educated while his contemporaries are seen as geniuses though their styles are similar; as one writes about Picasso: “the young genius destined to lead this movement.”[2] [3] Many of Lawrence’s contemporaries used inspiration from African masks in order to create their “primitive-style” Modern works – but was Lawrence equally inspired, or is this self-portrait created in pure cubist style and others project what they want to see on the work? And if it lacks this inspiration, how can this image be categorized instead?

In His Own Words

Throughout his entire career, art historians fall into analyzing Lawrence as an outcome of his environment, rather than looking at his works with a theoretical, formal, or analytical lens. As Peter Nesbett, a prominent art historian puts it, “First, they characterize his entire career through the lens of Harlem, where he lived roughly from the age of 13 until he was 26 (1930–43), with some extended out-of-town travel. (The majority of his adult life as a working artist was spent in Brooklyn and Seattle.) Secondly, they filter all interpretations through early formation and biography. For an artist who painted professionally for nearly sixty years, doesn’t this emphasis seem odd?” [4]

Much of this racialized lens stems from a 1936 essay by Alain Locke. Ultimately, Locke argues that African art must be a central inspiration for African-American artists, though also claims, at times, that the lineage between African culture and Black Americans is one that is hard to trace and quite separate from one another. [5] His essay became a point of high debate between various artists of various identities. James Porter, an African-American art historian, artist, and teacher, critiqued Locke’s pamphlet as follows:

Dr. Alain Leroy Locke’s recent pamphlet, ‘Negro Art: Past and Present,’ is intended to bolster his already wide reputation as a champion of Africanism in Negro art. This little pamphlet, just off the press, is one of the greatest dangers to the Negro artist to arise in recent years. It contains a narrow racialist point of view, presented in seductive language, and with all the presumption that is characteristic of the American “gate-crasher.” Dr. Locke supports the defeatist philosophy of the “Segregationist.” A segregated mind, he implies, is only the natural accompaniment of a segregated body. Weakly, he has yielded to the insistence of the white segregationist that there are inescapable internal differences betweenwhite and black, so general that they cannot be defined, so particular that they cannot be reduced through rational investigation.[6]

Porter and Locke taught at the same university during this time period, in art history and philosophy, respectively.[7] Using their debate, this essay hopes to break apart the traditional readings of Lawrence’s work, as desired by Locke, while pushing forward a possible new interpretation.

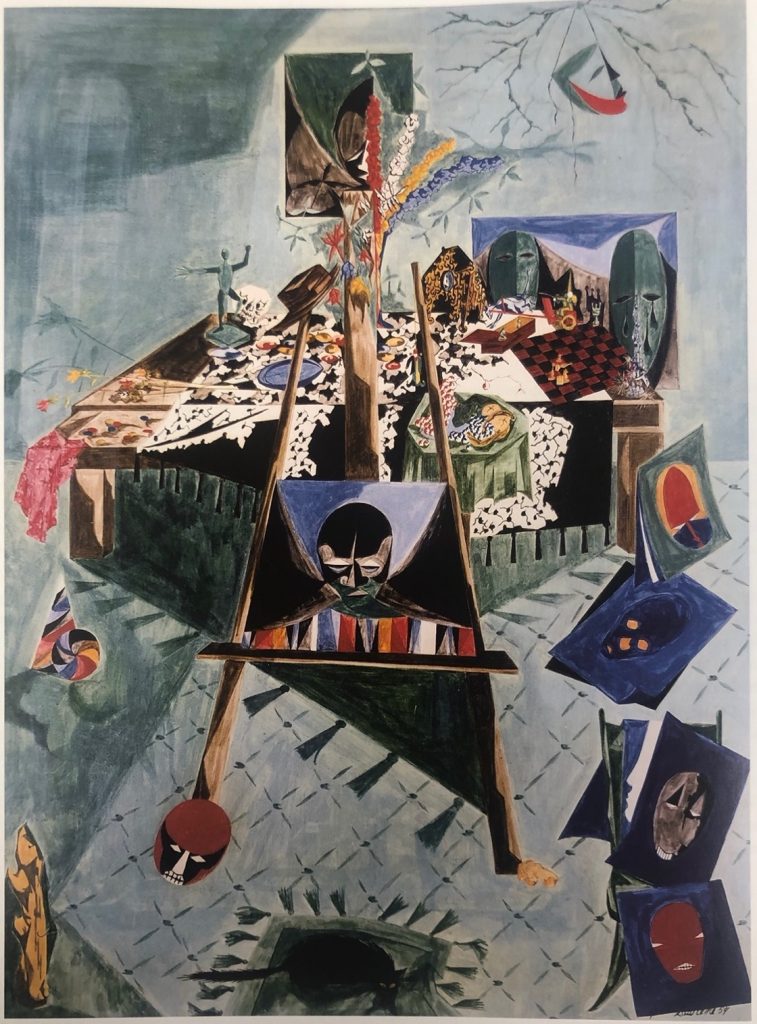

Of Lawrence’s 1977 self-portrait (fig. 1), a critic writes “His formidable expression challenges the viewer. But then one perceives that the sitter’s head seems to be floating on the surface of the picture plane, apparently kept in position by the right hand. Perhaps the face is merely a mask being help up for the benefit of the audience.” Bergman, the critic, seems to fall into the same trap that claimed Lawrence’s early works. The classical style which he mentions is an ode to traditional Modernist approaches, focusing on form, color, and a compressed picture frame. However, this critic claims what many others have also done; that Lawrence’s representation of self is understood as through a mask, rather than a flattened, cubist-style plane. In this image, Lawrence’s background consists of paintings that don’t actually reside in his studio which he seemingly felt represented him, both as an artist and individual. Works from his Harriet Tubman series and the Builders populate the frame, however, critics latch on to the idea of a mask rather than questioning how these reproductions may add to his identity and self-representation.

In an interview that took place less than a year before his induction, Lawrence states:

I went through Africa for eight months, but I realize that’s not much of an experience because I wasn’t born to. There are some young artists who hope to find this African- American idiom, this form. But I don’t know how they can because if you’re living in this culture, you’re a part of Western culture. To try to work like the African, the black American artist becomes pseudo something… I’d like to mention, though, that you can do it as a Western artist if you do it deliberately as Picasso did. You see, he did it in a very intellectual way to probe cubism. Many black artists also use African art, intellectually, to enhance the Western tradition in their work. We could go on and on with this but to answer your question very simply, I would say, no, I don’t see a particular black American style.[8]

To which the interviewer responded “Yet, some of your critics will stress the ‘African heritage’ which they believe is in your work. They always seem to do that with black artists. Whether it’s a writer, a painter, or what-have-you, both black and white critics will, from time to time, find some way to show a correlation between your aesthetic experience and African heritage.”[9]Lawrence seems to believe that his work falls within the Western tradition, and at most is intellectually stimulated by African art in order to enhance his art, not inspire it. Picasso’s primitive works found blatant inspiration from Africa, yet Lawrence wasn’t necessarily looking to do this. The intent of reflecting African culture or roots isn’t explicit in either his work or this interview response.

A few years later, Lawrence doubles down on this sentiment, claiming “You take the French Modernists such as Picasso and the Cubists — you have a very positive (African) influence there. I don’t think you see this as much in my work after my trip” as if African influence falls upon individuals of any race, inspires any artist. Yet, Lawrence’s style remained relatively the same, with him stating “I was very much motivated and stimulated by the marketplaces, the textures, the color, the movement-that was very exciting. So, I did about eight paintings on that theme-cloth markets, meat markets; this is what my content consisted of while in Africa. I really enjoyed being there. But this is not different from what I had been doing in the Harlem community before going to Africa.” Later, the interviewer asks: Do you feel your roots there (Africa) or do you feel them here? To which Lawrence responded “Well, I think I’m Western, if that’s what your question means. But this is a very difficult question to answer. My culture’s Western, yet I know my roots came from Africa, you see.”[10]

Lawrence’s Personal Style

Lawrence created a small series based on his time in Nigeria. The images look quite different than his 1977 self-portrait (fig. 1). Rather, the color, rhythm, and movement that Lawrence described in a later interview are prominent. Even in the heart of his supposed inspiration, Lawrence stays true to his style, drawing inspiration from texture and vibrant color, but not necessarily traditional art. Market Scene (fig. 2) maintains the same characteristics as those in his overarching library of works; layered colors and shallow planes which create a collage of overlaid narratives.

Lawrence created one image that focused on African masks, in 1954, about six years before traveling to Nigeria. Just as in his self-portrait, the image plane is flat, seemingly compressed into two dimensions rather than three. The masks are scattered around the room, painted in bright block colors that follow a loose Cubist style.

There are some similarities between his African masks and self-portrait. Lawrence sectioned off parts of the face, often differentiating between forehead and cheekbone/eye sockets. The slit-like almond eyes are also a prominent, unifying characteristic. While parallels can easily be drawn here, I argue that these methods of depicting individuals are prominent throughout Lawrence’s entire oeuvre, particularly in his earlier works. And, while the masks bear some resemblances to the style of African masks, Lawrence is working in a Modern style that can be traced throughout his entire career, cultivating into one self-portrait that is meant to define him, not only as an artist but as an individual as well.

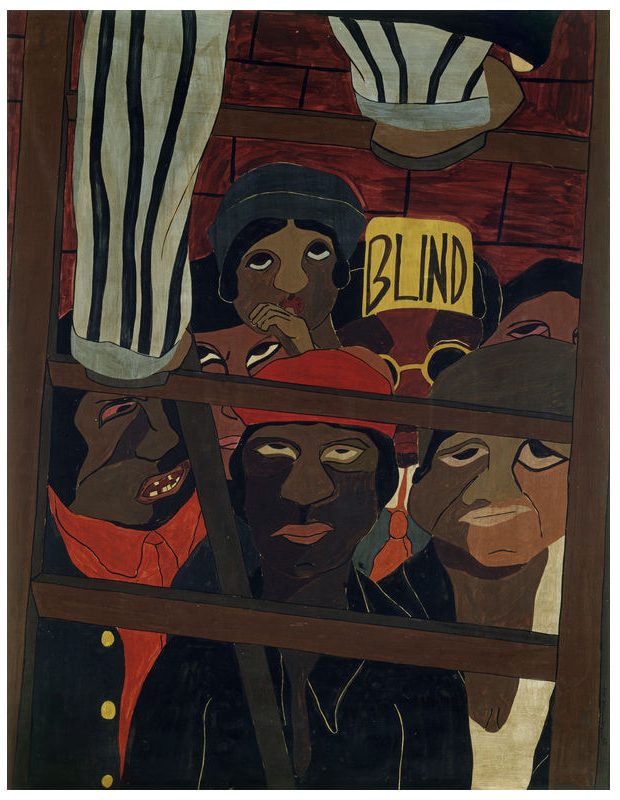

Lawrence’s use of block colors to create two-dimensional faces can be seen as early as 1936 (fig. 4). In Street Orator’s Audience, each individual is constructed of neutral shapes which form a face. Their eyes are even similar to those in his self-portrait. Lawrence’s long history of depicting faces on two-dimensional planes makes his self-portrait fall well within his traditional style, and yet pushes back against the projected Africa-inspired analysis that art historians place upon him.

Lawrence’s artistic practices deviate from traditional color-space theory, which theorizes how color can be placed in order to create a sense of depth on a two-dimensional plane (yellow “pops-out” and blue “sinks”). Even in his early works, Lawrence blends these spaces.[11] You can find an example in Street Orator’s Audience, the individual in the front is made up of the darkest skin tones, while another pops out of the background, consisting of the lightest colors. This same method is also prominent in his self-portrait; his face is painted with some of the darkest tones in the image. Merging and blending the layers in this way creates a collage-like image.

Artistic Inspirations

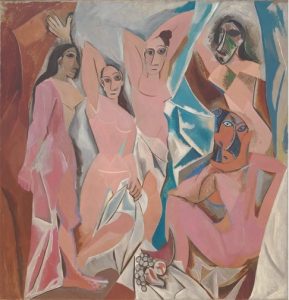

While the similarity between Masks and Self-portrait is fathomable, an even stronger relationship can be traced between other Cubist images and Lawrence’s. Lawrence mentions Picasso a few times during his interviews as an artist who is inspired by African art and uses it as inspiration for his work. The flat picture planes, blocks of color, and collage-like effects are prominent characteristics of Picasso’s work, for instance in paintings like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (fig. 5). If Picasso is inspired by African art, and Lawrence is inspired by Picasso, does that mean his work is inspired by African masks? Or, as Lawrence tends to claim, it is simply a Western portrait, as he is a Western artist.

Lawrence’s personal style can fall into the same cubist category as Picasso, as one can see from his Guernica, Self-Portrait, and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It is no surprise that Picasso drew inspiration from African masks; even Lawrence mentions it in his interviews. This inspiration can easily be found in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, where the faces, particularly on the right side of the frame, are made of stylized shapes and bright colors. Lawrence describes Picasso as explicitly inspired by African art and distinguishes his (Lawrence’s) own style from other Western artists who pursue the same inspiration. Lawrence seems to develop an Americanized cubist style.

Lawrence also states that he found inspiration from van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters series (fig. 7). From there, one can build a bridge between Lawrence’s use of block colors in the face and van Gogh’s rendering. Both artists use cool, earth tones and chunks of color in order to create their faces. Lawrence’s repeated return to this image implies inspiration to some extent. Lawrence states “I like symmetry, geometric design, composition, tonal color”[12]

While Lawrence discussed artists like Picasso and van Gogh, art historians continually placed him in conversation with other Black artists of his time, a prominent one being Romare Bearden. Bearden and Lawrence had different beliefs as to what being a Black artist in America meant. In a round table symposium, Bearden and Lawrence, along with a handful of others, were recorded in conversation, discussing what their roles and responsibilities were to their communities. Bearden argues strongly for an art that speaks to the Black community, claiming Black style is communicated through the image. Lawrence counters that without the artist standing beside the work, it is almost impossible to claim the racial identity of the artist. That their pieces are always placed in Black shows, rather than art shows. [13] While Lawrence remains proud of his identity and advocates for increased education and acceptance, he desires his art to be viewed through the lens of art, not a race.

Conclusion

Ultimately his self-portrait may be implicitly African-inspired but Lawrence made it clear that his art draws minimally from African culture and more from Western tradition. Calling this work mask-like without calling the work of Lawrence’s white, cubist contemporaries the same is a form of racial projection — they aren’t listening to the artist, himself. As he said, his roots may come from Africa, but his culture is Western. His roots may be hinted at in this piece, but ultimately Lawrence’s self-expression stems from the tradition set up by Modern painters.

Rather, Lawrence leans into a layering method that lends itself to a collage-like feel. Instead of Lawrence hiding behind a mask, he highlights the layers and depth to which he represents himself by reflecting those ideals in his artistic practices. He draws from Cubist techniques and pushes the traditional boundaries of the style by pulling it into his personal, American-art twist. The conventional “African” reading of this image relies on his biographical history for analysis, rather than placing his works in the realm art history as a whole.

While the claim “African-inspired” may be unsubstantiated, it is hard to negate that Lawrence did not pertain to a particular African-American style of art (one he may simply call American). The collage aesthetic is used by a plethora of Black artists, and while it may be mildly African inspired through the cubist route, I argue that it is a practice that deserves recognition beyond its hyper-raced analysis. Artists like Romare Bearden, Lois Mailou Jones, and Kara Walker all employ a form of collage and layering that is extremely identifiable. What can this new method of analysis tell us that an “African-inspired” lens can not capture? As you begin to look at this image in terms of layers, the narrative changes. Perhaps it highlights a disjointed history, one that is distorted and erased by white oppressors, denying a coherent, unified story.

- Berman, Avis. "Jacob Lawrence and the Making of Americans." ARTnews 83 (1984): 78. ↵

- Lawrence, Jacob, Brown, Milton W., and Whitney Museum of American Art. Jacob Lawrence. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974. ↵

- Patricia Hills. "Cultural Legacies and the Transformation of the Cubist Collage Aesthetic by Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Other African-American Artists." Studies in the History of Art 71 (2011): 221-47. ↵

- Peter Nesbett, "The Incomplete Jacob Lawrence." In American Masterworks from the Merrill C. Berman Collection, 2015. https://www.alexandregallery.com/catalogues/american-masterworks-from-the-merrill-c-berman-collection ↵

- Locke, Alain LeRoy. Negro Art : Past and Present. District of Columbia: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1936, 1936. ↵

- Bradley, Rizvana Natalie. "James A. Porter & Alain Locke on Race, Culture, and the Making of Art: A Roundtable." Callaloo 39, no. 5 (2016): 1169-185. ↵

- Bradley, Rizvana Natalie. "James A. Porter & Alain Locke on Race, Culture, and the Making of Art: A Roundtable." Callaloo 39, no. 5 (2016): 1169-185. ↵

- Major, Clarence. "Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, The Expressionist." The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977): 14-27. ↵

- Major, Clarence. "Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, The Expressionist." The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977): 14-27. ↵

- Rosenblum, Paula. "Seeing and Insight: An Interview with Jacob Lawrence." Art Education (Reston) 35, no. 4 (1982): 4-5. ↵

- Sims, “The Structure of Narrative: Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence’s Builders Paintings, 1946-1998” Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000. ↵

- Lovelace, Cary. "The Artist's Eye: Jacob Lawrence." ARTnews 95, no. 11 (1996): 79. ↵

- “The Black Artist in America: A Symposium.” Romare Bearden, Sam Gilliam, jr., Richard Hunt, Jacob Lawrence, Tom Lloyd, William Williams, and Hale Woodruff.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 5 (1969): 245-261 ↵