3 Building Portraits of an Educator

Education, Labor, and Community in Jacob Lawrence's Builders Paintings

Elizabeth Xiong

Abstract

After moving to Seattle in 1970, Jacob Lawrence dedicated the last three decades of his life to both teaching, and continuing his professional painting career. One recurring theme marked this period: the Builders. During this time, Lawrence’s fascination with tools, the architectural process, and labor coincided with a deep passion for education that stretched into retirement.

More universalist and less intimate, the Builders paintings have generally been read as a broad commentary on labor, America’s newest integrated workforce, and a symbol of Lawrence’s optimism towards that future. However, this generalized universality unintentionally blurs Lawrence’s personal stake in these paintings. Re-situating the Builders with Lawrence as an educator at its core, I place the builders theme in direct conversation with his personal teaching experiences in Seattle. With a representative selection of the Builders dating from his early years at the University to after retirement, and Lawrence’s own words paired with visual evidence, the paintings unfurl into portraits of an artist-builder. Ultimately, I argue that the Builders paintings are explicitly grounded in his identification with the builder through experiences as an educator in Seattle. In turn, by seeing each painting as a deeply personal portrait of Lawrence, it sheds light on his vision, legacy, and optimism for the future.

“My belief is that it is most important for an artist to develop an approach and philosophy about life — if he has developed this philosophy, he does not put paint on canvas, he puts himself on canvas.”

— Jacob Lawrence, 1986[1]

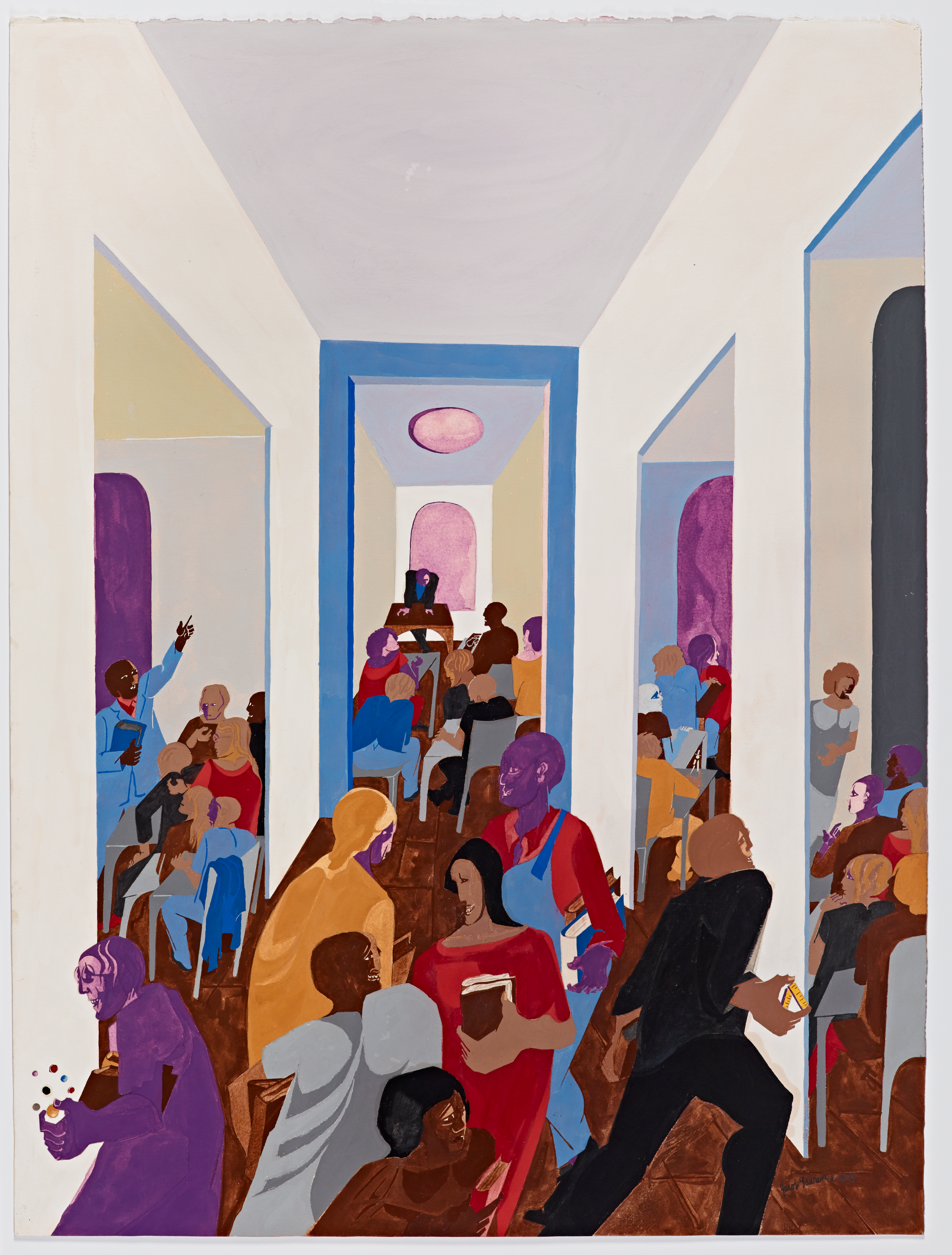

In 1977, six years after accepting a full professorship to the University of Washington, Jacob Lawrence painted University (fig. 1), where a bustling hallway full of students first fills the scene. These seven figures seamlessly flow past one another shoulder to shoulder. Two are making eye contact while the others appear to be deep in thought, perhaps pondering the class they just left or thinking ahead to the next. Looking slightly above these students in the foreground, and suddenly the brilliant white walls of the hallway guide our eyes deep into the three classrooms that line the painting’s edges. This is a scene many of us have yet to experience after a year of remote learning, however, Lawrence still beckons us into the moment with his use of strong linear perspective. At the same time, boisterous sounds of footsteps, listening, and learning seem to emerge from the painting through the vibrant colors and bold figures that fill every conceivable nook.

It’s long been established that the works Lawrence created before his permanent move to Seattle in 1971, from the earliest genre scenes depicting life in Harlem to his multiple historical series, are rooted in his lived experiences. Importantly, the artist himself once described all of his works as portraits of himself, his family, his peers, that they are a part of him.[2] But what of the works created from 1970 onwards? At first glance, that connection to an intimate portrait may seem to waver. Page after page of his catalogue raisonné are filled with paintings of builders, buildings, and construction scenes. The only explicitly education themed work from his time in Seattle was University. That then raises the question: if Lawrence himself was never a construction worker, but worked as a professor of art during this time, why did he choose to complete over forty paintings with the builders theme that spanned three decades? Taking Lawrence’s own words as a starting point, this essay explores his dedication to the theme of builders within the context of life and work in Seattle, and argues that these works function as a collective portrait of the artist as an educator. A closer look at the Builders paintings sheds crucial light on how he “puts himself on canvas” through his pedagogy, the powerful relationship between labor as an educator, and community-building through art education.[3]

Despite limited scholarship on Lawrence’s later career, prominent scholars who have turned their attention to the Builders, guide our initial approach to the series especially in regards to the paintings’ formal elements and content. In one of the only sustained analyses of the series, art historian Lowery Stokes Sims analyzes the unconventional compositional design and color of the Builders through the lens of Lawrence’s early education in Harlem, as well as Josef Albers’ later influence following their time together at Black Mountain College in 1946.[4] Importantly, Sims champions a universalist approach to the philosophical and social notions of construction which symbolize “American worker culture, especially in the African American community.”[5] Her analysis of the individual formal elements on canvas, in light of a universalist interpretation is not incorrect, but I contend that without a personal interpretation grounded in Lawrence’s own experiences, it is incomplete.

On the other hand, co-director of Lawrence’s catalogue raisonné Peter Nesbett argued the Builders paintings’ “content remained personal,” but only to a certain extent of “renewed exploration of [his] self-identity.”[6] This began to fill in what Sims’ universalist reading left out, however Nesbett still found that the paintings lacked the personal experiences that Lawerence’s earlier works were grounded in.[7] In turn, he identified only two paintings where Lawrence’s identification with the builder was explicit enough to be considered as a portrait of expression.[8] Nesbett’s emphasis on the personal content of the Builders is vital, however the oversimplification of the relationship is diluting, and takes Lawrence’s teaching experiences at the time out of the conversation. His methods and experiences as an educator have, therefore, been generally understood from a biographical standpoint, and isolated from any discussion of his work.

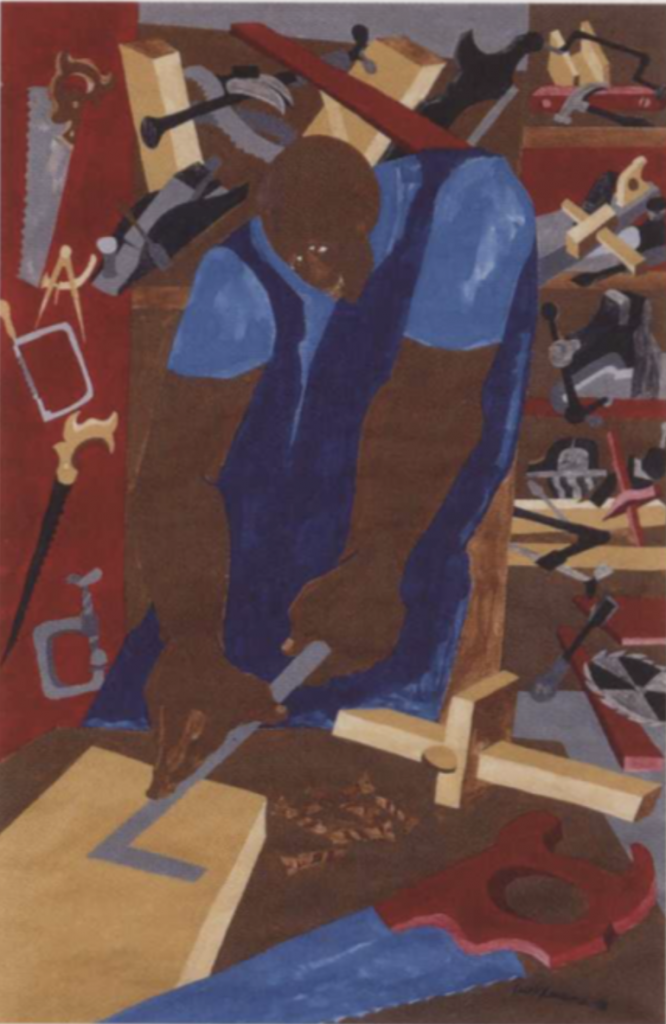

Lawrence’s own focus on the “formal means of picture making” characterize much of the Builders’ style, and becomes a starting point to see his pedagogical identity at work in those scenes.[9] For instance, Lawrence skillfully camouflages the man in his workplace in Man With Square (fig. 2), and at first glance it is hard to differentiate where the structures around him begin, and the outline of his body ends. This ambiguity in the picture plane is further accentuated through the protruding three-dimensional tools enveloping the man, juxtaposed with his two dimensionality. Defying the natural relationship between objects in space, Lawrence is not merely recording a builder at work, but floods it with experience. Lawrence was first exposed to cabinetmakers with their tools when he was fifteen, evidently it became a meaningful motif for him.[10] He therefore paints how he feels tools and builders interact in space according to his own experiences, all of which is a freedom that is core to his teaching philosophy. In his pedagogy statement, he stressed above all else for his students to not just record and look, but see and experience how subject matter makes them feel.[11] Hence, the teaching philosophy he imparts on his students goes hand in hand with his own philosophy on life — one “of seeing.”[12] He once remarked that a philosophy is “most important for an artist to develop,” because it “puts himself on canvas.”[13] Therefore, through the Man With Square’s formal composition and content, we see his teaching philosophy on canvas. We begin to see him on canvas.

Given this powerful connection between built structures and the bodies building them, the prominent presence of architecture in the Builders works cannot be overlooked. It is through architecture that we gain a deeper awareness of Lawrence’s presence in these images as both builder and educator. In his teaching statement, Lawrence posed the question: “you can have all the skill in the world, and turn out to be merely a renderer, but how can you build on that?”[14] Unsurprisingly, his answer was three words: experience, living, seeing.[15]

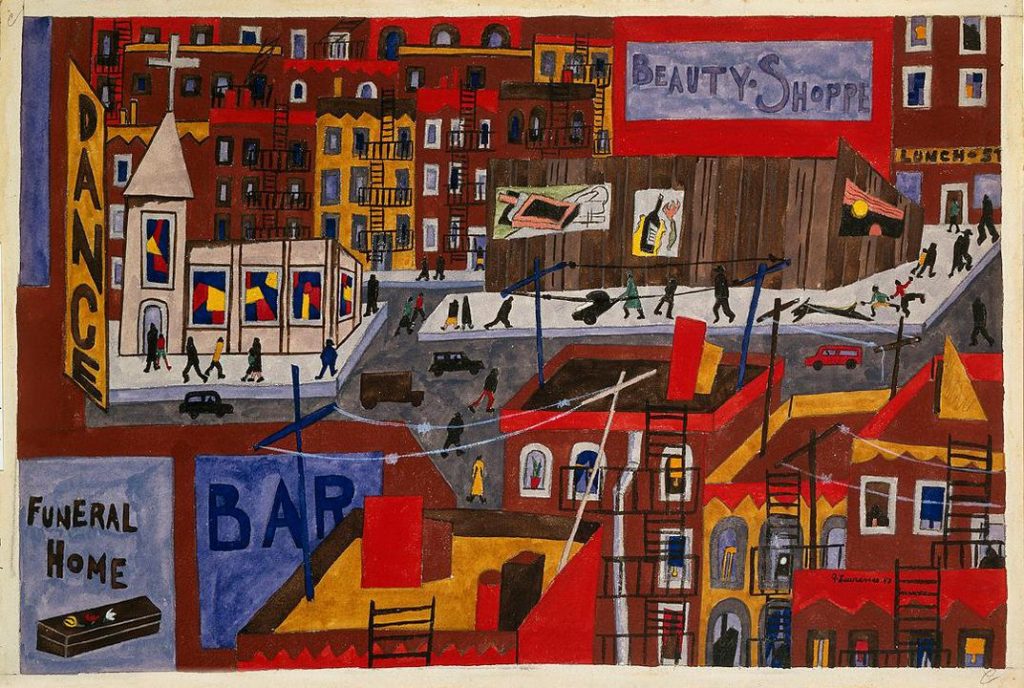

In Builders — 19 Men (fig. 3) we see a familiar landscape — Harlem. Rows of colorfully crooked buildings stretch across the horizon, and if we stood on those streets perhaps we would be stepping into his iconic painting This is Harlem (fig. 4). In an interview with the Seattle Public Library, Lawrence remarked on the tight formal and conceptual coupling of human form and structures, which originated from his time in New York.[16] But when we concentrate on the distant east coast location as the sole place where Lawrence “put himself on canvas,” we overlook the complex human-structure relationship he built on the west coast. That relationship is visible here: he paints the building being built as the main attraction, placing it right before our eyes. Therefore, incomplete structures equally serve as another portrait on canvas, evoking the ongoing experience establishing oneself in a new city, and creating new relationships, all of which drove Lawrence’s life’s philosophy. Once again it is in his philosophy, not only his face, that we see him on canvas, exactly as he portrayed it.

Looking back at the amalgamation of men and tools in Builders — 19 Men, Lawrence’s focus on the process leading up to a completed architectural endeavor (rather than on the finished building itself) is key in continuing to dissect pedagogy as portrait. Moving from the finished skyline downwards, working men carry individual horizontal planks to build the city, and the painting before our eyes. In the same way, Lawrence emphasized the basic elements of texture, value, line, and color collaborating to develop a work in his teaching.[17] He championed these small elements, where a line isn’t just a line, but has “a certain beauty to it,” and believed in their unified concentration.[18] Similarly, when describing what was a part of him, Lawrence emphasized the seemingly isolated experiences and paintings that ran through his life as one unified strand.[19] Accordingly, in Builders — 19 Men and other Builders paintings, he constantly showcased the individual pieces of wood, metal, tools, and workers that are vital to completing an intricate final product. Therefore, wood can be seen as texture, metal as value, tools as line, workers as color, and these essential elements on canvas equally portray who he was through his personal teaching methods.

In addition to the Builders reflecting Lawrence’s self-conception through his philosophies, his dedicated depiction of the workforce points to an intersection between the builder’s labor, and his own labor as an artist-educator. On the topic of carpentry and tools, Lawrence recalled, “I never thought I’d be using this content in my painting, but evidently it was having a great meaning for me,” especially during his time at the University of Washington when the theme regularly occurred.[20] Similarly, after retiring, an interviewer asked if Black Mountain College conditioned him to teach. He replied “no… I never thought of teaching, and I’ve never applied to any places to teach. I’ve always been invited.”[21] The convergence of these two strands in his life, experiences that he did not foresee, land directly on a target whose bullseye is the Builders paintings.

Depicting construction laborers of all types, Lawrence consistently made personal identifications with the builder’s labor on canvas. Nesbett first tackled this relationship, but only attributed the connection to Self Portrait and The Studio.[22] However, paintings containing tools, and labeled as a self-portraits cannot be the singular determining factor of that relationship. So how can we continue to see Lawrence in the Builders, moving beyond philosophy, and into the explicitly figurative? Captions are powerful clues onto meaning, and through Artist with Tools (fig. 5) Lawrence nudges us in the right direction.[23] He did not name this work ‘Builder with Tools,’ but intentionally chose the word ‘artist.’ Throughout his artistic career, Lawrence did prolonged archival research, laboriously planned and often painted panels color by color, all of which is labor.[24] The assembly line nature of his work had an end goal: to reveal accepted truths to those in his community while educating, and challenging others during pivotal moments in American history.[25] Sitting with carpentry tools and paint brushes as one unit, the artist’s posture is reminiscent of a traditional portrait. His overalls indicate he is a builder, yet the delicately curled brushes indicate he is an artist. Lawrence pulls these two identities together, just like the items in the builder’s hand, through his role as an educator building stories and paintings on canvas.

Furthermore, a comparison with Self-Portrait (fig. 6) paves the way to more concretely see Lawrence as the builder. The strikingly similar formal qualities between the two figures is key. Both heads are tilted to the same degree, the artist in overalls looks down in contemplation while Lawrence rests his chin on his hands. His signature moustache also makes an appearance in Artist with Tools, along with a shared handful of brushes. These distinctive commonalities between a known portrait and a Builders painting help further ground Lawrence’s identification with the builder. Here, he is that artist who sits reflecting on his labor, and what he has built.

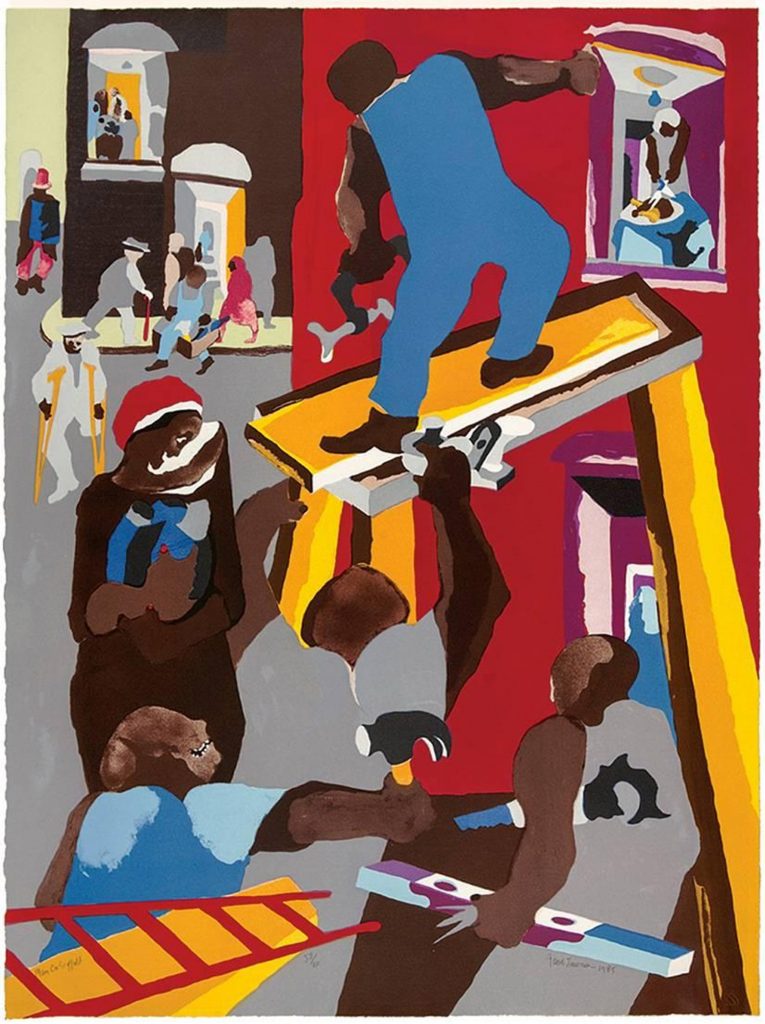

Completed eleven years after Lawrence retired, Artist with Tools not only paints Lawrence reflecting on his artistic career, but it also becomes a definitive portrait of how he saw his role as a professor of art in the builder’s theme. For Lawrence, there was an “aesthetic beauty in how the tool emerges from the hand and how the hand itself is a beautiful tool.”[26] The ruler and hammer seamlessly flow out of the man’s hand, but it is the paintbrush that looks like a true extension of the artist’s fingers. Lawrence therefore draws this parallel between the tool accentuating the beauty of a builder’s hand, and the brush accentuating the power of a painter’s hand. As a professor, he ties that directly to teaching students “how beautiful a tool is — how it’s a symbol of uplift, a symbol of building, a symbol of achievement.”[27] Although the late 20th century marked fierce technological innovation, Lawrence exclusively placed these old fashioned tools that required the skill of humans in the hands of his builders. Likewise, he put brushes and ambition in the hands of his art students, guiding them to see their capacity to achieve.

This picture of Lawrence’s labor as an educator is therefore not complete without the students he worked with. On the left side of the painting, seven other builders scale a tall building, and the ladder stretches out below the bottom of the frame, merging with the cropped feet of Lawrence as the artist. Here, he does not correct their lopsided ladder, but holds it in place, allowing them to climb, and build something for themselves (which can be seen in the windows that hang on the building like framed paintings). Likewise, Lawrence’s presence in the classroom was never one of condescending critique, as he repeatedly stated that his job was to find a student’s strong points, and build (emphasis mine) on them.[28] His MFA student and friend Barbara Earl Thomas concurred with this sentiment when she described Lawrence as “someone in the classroom guiding you without dominating you,” which is present in this portrait of Lawrence as a builder-educator due to the balanced proximity between his climbing students and himself.[29]

The student and teacher’s matching overalls additionally emphasize Lawrence’s belief that “teaching is a two-way thing. It has enabled me to learn and expand in ways I may have not, both in my work and in my thinking.”[30] The builder as a symbol of constructive growth for all parties illustrates that sentiment. Therefore, the full picture of Lawrence’s labor as a professor is intricately rooted in his desire to give as a teacher, but also continually receive as a student. This developed from his time at Black Mountain College, where he was first invited to teach, but found what he learned about design and pedagogy from fellow colleague Josef Albers most valuable.[31] In turn, within this Builders painting and those beyond this one, the builder becomes a recurring motif that Lawrence uses to directly illustrate his labor and role as an educator to build upon the skills of his students, and his own.

In addition to the Builders paintings serving as a portrait of experience through Lawrence’s philosophy and labor as an educator, the historical context surrounding his arrival to Seattle is key to repositioning his emphasis on an integrated workforce from purely universalist to personal. Jumping back in time once more, two years before Lawrence accepted his professorship, he participated in the groundbreaking The Black Artist in America Symposium as a roundtable panelist. In conversation with fellow artists including Romare Bearden and Tom Lloyd, Lawrence stressed that in order to continue solving the issues facing Black artists, it was “going to take education – educating the white community to respect and to recognize the intellectual capacity of Black artists.”[32] He warned against an isolationist approach that the younger artist Lloyd proposed, and instead saw the most productive potential for change in an integrationist one. However, despite his clear stance on using paint “instead of using words,” Lawrence was often pressured to voice the value he saw in educating white students out loud. [33] After moving to Washington state, whose population in 1970 was roughly 95.4% white residents and only 2.1% African American, critics continued to “[grumble] about him living in a white neighborhood and teaching mostly white students.”[34]

Nevertheless, even without many words, this optimism towards integration Lawrence painted in the Builders, where white and Black construction workers labor together in the same space, is directly rooted in his belief that time spent educating white Americans is a powerful, constructive tool against injustice. A prime example of this is in Builders No. 3 (fig. 7), where a single white builder looks up with an expression of awe at two Black builders assembling the wooden structure’s walls by hand. The two are educating the one on their craft as their bodies swirl left and right up towards a point that coincides with the mountainous peak behind them. Lawrence therefore utilizes the integration of their physical bodies to portray his labor charting a path to overcoming the mountain of struggles facing Black artists, through his experiences in overwhelmingly white classrooms. It is in these spaces, through his work of both painting and teaching, where Lawrence saw his commitment to fighting injustice.[35]

Furthermore, as Lawrence entered into retirement, harmonious integration in the Builders paintings shifted from specific scenes of builders and their craft, to their presence within the community. In these community scenes, namely Images of Labor, Community, and Builders — Man on Scaffold (fig. 8), Lawrence often painted laborers reinforcing the community’s foundational structures, while members of their community flow past them as anchors of support. Notably in Builders — Man on Scaffold, an integrated crowd of men and women stroll past each other in the background, and others peer through the windows onto streets reminiscent of Seattle’s. Accordingly, Lawrence explicitly painted each builder as permanently present in the community. The central figure supporting the scaffold becomes one with the pavement as his overalls coalesce into the ground he stands on, while the builder on the scaffold looks to be grabbing the red structure’s window by its frame, pulling it into alignment. The builders’ anchored presence among those he works for is therefore grounded in Lawrence’s personal presence in Seattle’s predominantly white population. It powerfully highlights his belief that the “only” way to “improve a society” is to live “totally within a society, not by being an outsider,” and the ways in which he put that belief into action.[36]

Community support for the arts was a major factor in Lawrence’s development as an artist, and the Builders continue to show his efforts to build that same community during his time in Seattle.[37] The builders in these community oriented paintings never work alone. Similarly, Lawrence cherished collaboration with local museums, children’s programs, and public schools to reach those he was building for. A brief scroll through the Archives of American Art’s digitized collection of Lawrence’s correspondence papers shows twenty three folders from schools in Seattle all the way to Georgia. For example, from 1985 to 1994, Lawrence worked with the Bellevue Art Museum to develop educational art programs. Additionally, slide after slide of bright children’s paintings, inspired by him, fill the folders (fig. 9). Letters from grateful public school teachers and alumni also beautifully illustrate that this integrated community-building vision through art education was an immensely personal one. Importantly, this ambitious vision continues, even after Lawrence’s passing in 2000. For example in 2015, the Savannah College of Art and Design launched a K-12 curriculum guide based on the Builders paintings that were translated into prints.[38] Symbolizing this continuation, the builders in each painting have not stopped, but continue to stand, communicate and work together.

Bringing the universalist interpretations of the Builders paintings back down to Lawrence’s own personal experiences in Seattle, and seeing each work function as a unique portrait of himself as an educator has not only clarified his identification with the builder, but also clarifies ours. Overall the builders theme is a coherent whole, conveying notions of teaching, labor, and community. However, each painting equally speaks volumes for itself, unable to be generalized. In the same way, as we look at each painting individually, and see the ways in which Lawrence has put himself on canvas, what does he motion for us to see? I believe he assures us that his ambitions are not unreachable universalist notions, but instead that they are reachable, personal teachings derived from experience. Take one more look at University, the painting we started with, and Lawrence shows us how.

The paper thin walls, and textured floorboards all draw attention to the materiality of the space, the same materials evident in the Builders paintings. The purple figure in particular, dressed in overalls, but clutching two books rather than tools, furthers this physical connection between building as a verb and the places where education happens. Likewise, Lawrence continually emphasized throughout the Builders paintings that the potential to ignite change, and build something meaningful, lies within the individual. From the tools of a builder to an individual’s ongoing education, it is just a matter of getting on the scaffold, and out into the community in order to build upon the legacy he left, in our own uniquely personal ways.

- Jacob Lawrence, quoted in Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986), 73. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, interview with Elizabeth Hutton Turner, Seattle, Washington, October 3, 1992, quoted in Lonnie G. Bunch and Spencer R. Crew, “A Historian’s Eye: Jacob Lawrence, Historical Reality, and the Migration Series.” In Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, ed. Elizabeth Hutton Turner, 30. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986), 73. ↵

- Lowery Stokes Sims, “The Structure of Narrative,” in Over the Line, ed. Peter Nesbett and Michelle DuBois (Seattle and New York: University of Washington Press, 2000), 208-209. ↵

- Sims, 209-210 ↵

- Peter T. Nesbett, “Jacob Lawrence: The Builders Paintings,” in Jacob Lawrence: Builders (DC Moore Gallery, 1998), 5-22. ↵

- Nesbett, 17-18. ↵

- Nesbett, 18. ↵

- Julie Levin Caro, “The Legacy of Black Mountain College on Lawrence’s Art Pedagogy,” in Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence and Black Mountain College, ed. Julie Levin Caro and Jeff Arnal (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 78. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence 1993 interview excerpts, quoted in Peter T. Nesbett, Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints, (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 31. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence et al., “Faculty Notes,” in Drawing, at the Henry: An Exhibition of Contemporary Drawings by Eighteen West Coast Artists (Seattle: University of Washington Press), 1980, 52-53. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, interview by Mary Emma Harris, Black Mountain College Project, March 1, 1998, quoted in Julie Levin Caro “Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College Summer 1946” in Lines of Influence, ed. Storm Janse van Rensburg, (Zurich: Scheidegger and Spiess, 2020), 133. ↵

- Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter, 73. ↵

- Lawrence, “Faculty Notes,” 53. ↵

- Lawrence, 52-53. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence - #1,” interview by Donald Schmechel, The Seattle Public Library, July 27, 1987, audio, 1:45:0, https://archive.org/details/spl_ds_jlawrence_01_01. ↵

- Lawrence, “Faculty Notes,” 52. ↵

- Lawrence, 52. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, Distinguished Faculty Lecture, University of Washington, 1978. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, quoted in Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints, 27. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence - #1,” by Donald Schmechel, audio, 1:11:06. ↵

- Nesbett, “Jacob Lawrence: The Builders Paintings,” 18. ↵

- Leah Dickerman, “Fighting Blues,” in Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, ed. Leah Dickerman and Elsa Smithgall, (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2017), 20. ↵

- Milton W. Brown, Jacob Lawrence, (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974), 11; Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence” in Over the Line, ed. Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 104. ↵

- Lonnie G. Bunch, “Historian’s Eye”, 30. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, interview with Patricia Hills, January 11, 1994, quoted in Patricia Hills, “The Prints of Jacob Lawrence: Chronicles of Struggles and Hopes,” in Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints (1963-2000), ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 16. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, quoted in Los Angeles County Museum, “Jacob Lawrence | Artist Interviews,” Youtube Video, April 28, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WdXz_D8t_qs&t=782s. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, quoted in typescript of “Profile of an Educator” for Campus Report, 14, January 1975, Box 5, Folder 14, Image 37, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers correspondence, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; Micheal Spafford, quoted in Julie Levin Caro, “The Legacy of Black Mountain College on Lawrence’s Art Pedagogy,” 80 ↵

- Barbara Earl Thomas, quoted in Los Angeles County Museum, “Jacob Lawrence | Artist Interviews,” Youtube Video ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, quoted in typescript of “Profile of an Educator.” ↵

- Julie Levin Caro, “The Legacy of Black Mountain College,” 80. ↵

- Romare Bearden et al., “The Black Artist in America: A Symposium,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 5 (1969): 246. ↵

- James Halpin, “My Neighbor Jacob Lawrence,” Oct 7-13, The Weekly, 1987 Box 7, Folder 16, Page 15, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers correspondence, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; Jacob Lawrence quoted in “Jacob Lawrence: An Intimate Portrait, 1993.” ↵

- John Caldbick, “1970 Census: Women outnumber men in Washington State for the first time; Seattle and Spokane lose population as Tacoma and Everett gain; early baby boomers approach adulthood,” HistoryLink.org, last modified May 18, 2010, https://historylink.org/File/9426; James Halpin, “My Neighbor Jacob Lawrence,” Oct 7-13, The Weekly, 1987 Box 7, Folder 16, Page 15, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers correspondence, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, “Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, the Expressionist,” interview by Clarence Major, The Black Scholar 9, no.3 (1977): 19. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter, 113. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, “Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, the Expressionist,” 19. ↵

- “History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence,” SCAD Museum of Art Curriculum Guide K-12, SCAD Museum of Art, 2015. ↵