10 Intellectual Labor

Jacob Lawrence and the Library

Bailee Strong

Abstract

This article follows the development of representations of libraries in Jacob Lawrence’s work throughout the twentieth century. Images of libraries persist over the expanse of his career through social unrest, popular art movements, geographical location, and artistic evolution, therefore cementing the significance of this iconography beyond a singular image. Schomburg Library (1987), a painting commissioned for the library of the same name in Harlem, makes an important departure from Lawrence’s other depictions of these spaces of education. When compared to works such as Builders- Man on a Scaffold (1985), Schomburg Library modifies the definition of labor to expand beyond the physical. While many of the paintings in the Builders series are of traditional carpentry and woodworking, images such as The Builders Family (1993) show parental duties as its own kind of industry.

Early in Lawrence’s career, he painted The Libraries Are Appreciated (1943) with the bustling energy of those who are eager to learn; the focus on people actively in charge of their education is carried throughout each iteration of the theme. The artist would continue to expand upon this theme over the decades, eventually creating Schomburg Library and directly addressing his history with the collection housed there. In preparation for various series throughout the mid-twentieth century, Lawrence delved into the archives of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. This research took months to complete and is itself a form of intellectual energy; Builders- Man on Scaffold parallels the physical labor of construction to the intellectual development symbolized by Schomburg Library.

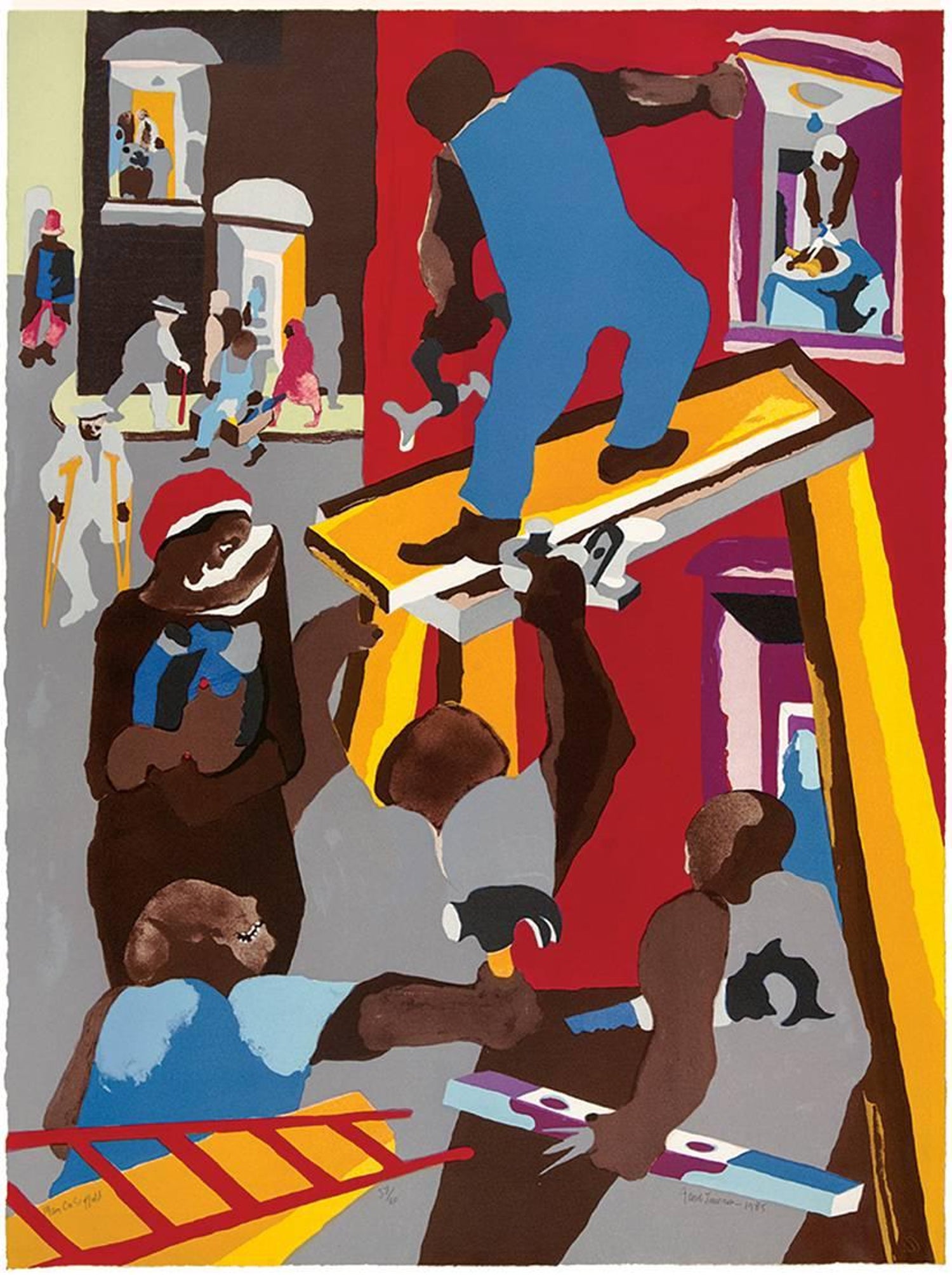

As a history painter himself, Lawrence understood, better than most, the importance of the library as a powerful source of inspiration. Lawrence was a young teenager during the Great Depression in Harlem, New York, and was encouraged to take advantage of public resources in the community- many of which were within walking distance of one another.[1] Being within close proximity to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture made his subjects for paintings in the 30s, 40s, and 50s all the more accessible.[2] The stories of heroes and heroines of history that had been told to him through street orators, teachers, and librarians were available to research and bring to life.[3] In order to create historically informed paintings, he translated documents to tell the story of the primary and secondary sources he researched extensively.[4] The amount of work required to produce these images is immense, and this is acknowledged through a mirroring of the formal qualities of Schomburg Library and Builders- Man on Scaffold (fig. 1, fig. x). A common depiction of labor in Lawrence’s work manifests in images of construction workers under the Builders’ theme, such as Builders- Man on Scaffold, however, this representation begins to unravel in depictions of builders who do not perform this version of physical labor like The Builders Family. An exploration into Lawrence’s depictions of labor expands the definition beyond the physical industry. Using the same visual conventions, Schomburg Library is treated as if it is part of the Builders theme in parallel intellectual labor required in Lawrence’s practice to physical labor in scenes of construction.

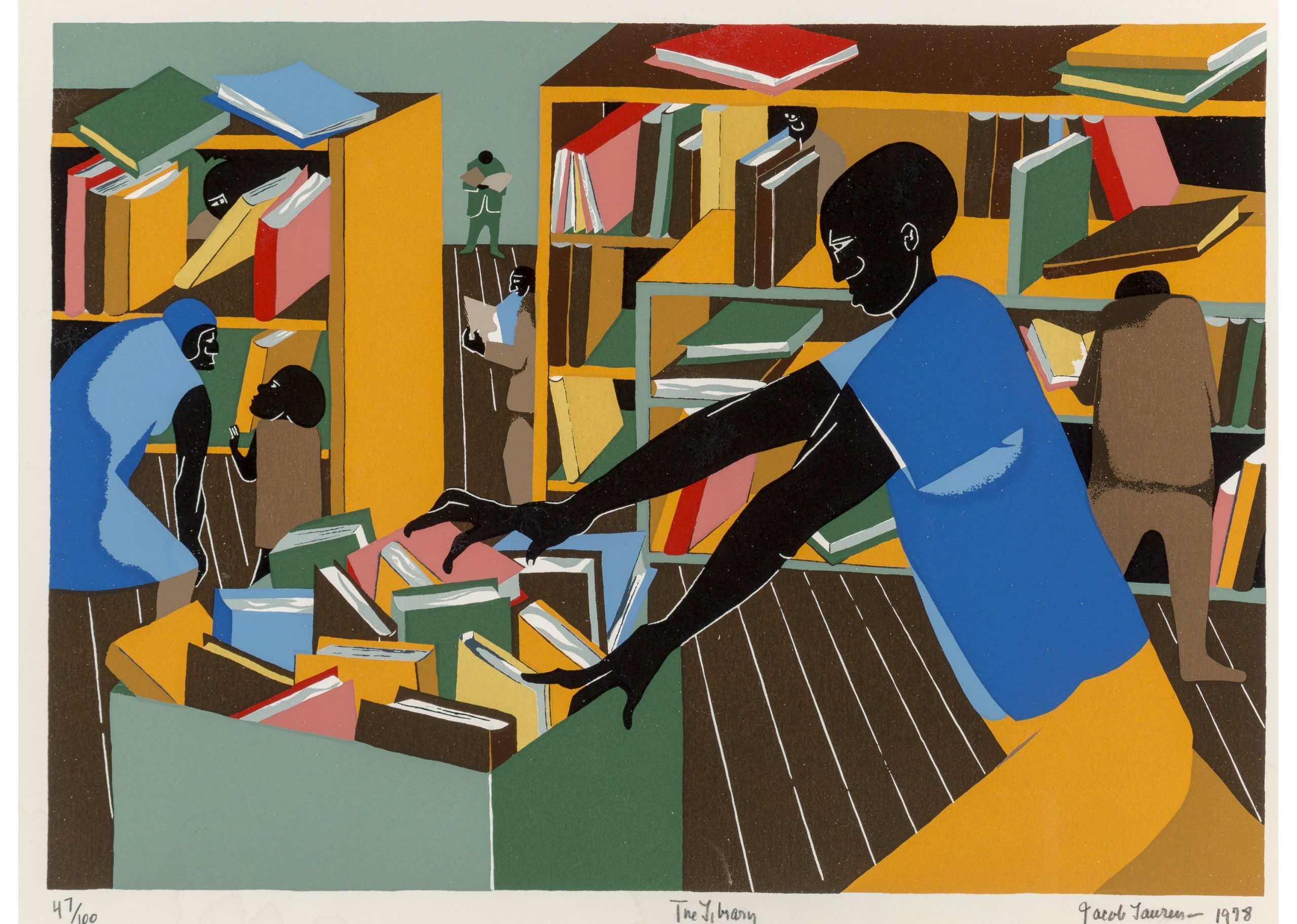

Jacob Lawrence depicted the library in varying conditions and styles throughout his career from The Library (fig. 2, 1960) to Schomburg Library (1986), all of which maintain a high level of respect for the information and community these spaces provide. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture was the main archival source for Lawrence’s historical paintings, such as the Migration series. In an interview with Carroll Greene, Lawrence stated, “Yes, I did quite a bit of research. I was fortunate in that we had the Schomburg Library, which had become one of my favorite places to go… work and do research. And this is where I think I read many books, Du Bois and many books like this.”[5] He used these public documents to translate into a visual story that exemplified the wealth of knowledge and inspiration of primary sources.[6] This library serves the community of Harlem with a wealth of resources in its collection. The community was so involved after the opening of the “Division of Negro History, Literature, and Prints” in 1925, in fact, that the institution could not replenish books at the same pace they were consumed by the public.[7] The opening of the Arthur A. Schomburg Collection would become a priceless resource for Lawrence’s career as he spent months of time researching for paintings such as the Migration series.[8] Lawrence said about his research process, “I would go to the Schomburg Library and read books on these various personalities. I would take plenty of notes. Then I would go back to my studio and peruse the notes and edit them. I would select notes that describe an action that I could visualize as a painting.”[9] In order to identify the key moments for a composition, Lawrence would read through his sources, take extensive notes, and revise them repeatedly to eliminate any extraneous details.[10] This ensures his images will distill the crucial moments in history that he has discovered in the archive. As a result of this work, his paintings serve to encourage others to delve into the wealth of knowledge available as well as become an even more accessible piece of history.

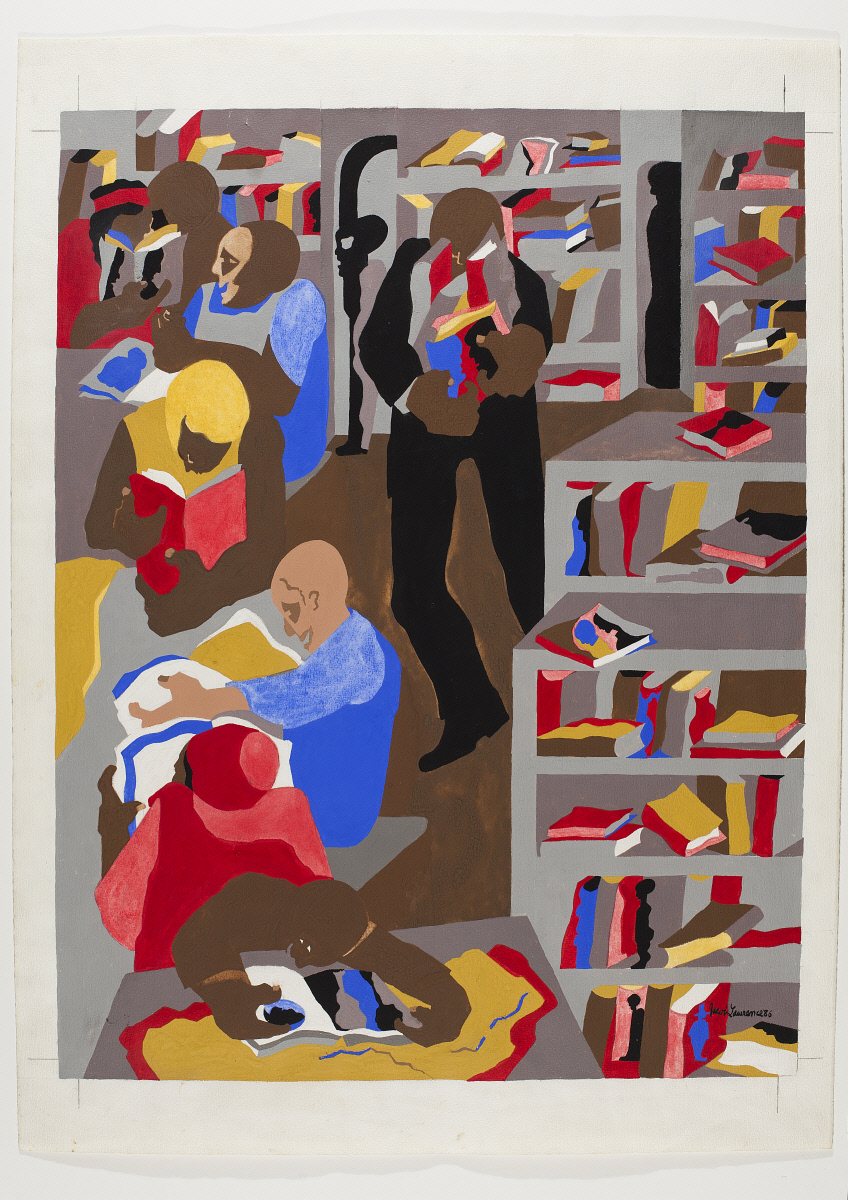

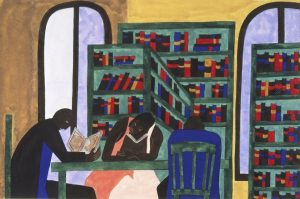

In contrast to previous iterations of the library theme, such as The Libraries Are Appreciated (fig. 3), the composition of Schomburg Library stacks the figures within a vertical frame. Warm tones of brown and grey serve as a public invitation into the room while simultaneously forming a narrow aisle full of energetically formed human figures. Brown and grey dominate the color palette to ground the composition and provide a clearer sense of direction. Additions of red, blue, and yellow not only invigorate the palette but provide movement with the oscillation of cool and warm tones. The planes of the composition are flattened as if they all exist on the same surface; the red and blue elements contribute to this flatness by creating a visual illusion of receding and protruding throughout the composition. Even with this perception of flatness, there is still a feeling of activity.[11] The central figure, a man walking toward the viewer, is carrying an inordinate number of books in his arms that he struggles to carry. Another figure in the foreground excitedly turns the pages of a magazine that he hunches over with a smile. The composition is lined on one side with figures actively reading while the opposite displays the sheer number of novels yet to be studied. The line quality contributes to the contained chaos as the shapes resist hard edges or geometric shapes; bodies are pliable, books are warped, and shelves are interrupted by curved sculptures. Excess at every turn, this scene embodies the wealth of knowledge there is to gain from the library. The color of the floor blends the figures into the architecture of the ground, and the color of the book covers mimic the figures’ clothes; the figures become a part of the fabric of the library itself through Lawrence’s use of form and color. In conversation with Clarence Major, Lawrence said that “As you move up you have form and content. You can’t separate them. For a work to be successful they must merge. The ideal is for them to merge so you can’t separate them.”[12] The forms created by blocks of color merge to become the fabric of the library which cannot be disconnected. The public is what keeps the library alive and invigorated; it is a communal and reciprocal relationship.

Always observant, Lawrence used similar visual constructions and took inspiration from his community when he began to paint scenes of carpenters and various laborers amid energetic construction for his Builders series.[13] Lawrence addresses his subjects in an interview with Xavier Nicholas when he says:

“I’ve always dealt with my experiences, either directly or indirectly. My work in that way is autobiographical… The Builders paintings come out of my experience being around cabinetmakers when I was a youngster. I paint my impressions of the things I know about and the things I have experienced… I just try to put down my emotions and feelings about how I respond to my surroundings. That’s what I’m trying to do in my paintings.”[14]

This emotional interpretation of labor contributes to distinct features recognizable in the paintings under the Builders theme. The perspective of later Builders images, such as Builders- Man on Scaffold, is severely tilted and elevated above the horizon while the imagery is formatted in a narrow vertical composition, giving the audience an expansive view of the scene.[15] The painted tools, construction material, and bodies assist the transition between planes and contribute to the pyramidal figure that places the focus at the apex; the energy nearly pushes the figures from the edge of the painting as they are collected in the foreground.[16] While Lawrence’s Builders series primarily concerns images of carpenters and construction workers, these are not the only figures depicted hard at work. The Builders Family, for example, shows the exhausted man at the head of the table with his tools spread throughout the room, while a mother figure steps in to care for their family (fig. 4). The vertical aspect ratio prioritizes detail for the tools, places the laboring figure at the apex of a pyramidal arrangement, and tilts the perspective to view the subjects from a higher angle. These qualities parallel the labor required to care for a house and family to the construction performed by manual workers in the series. This unorthodox vision of Builders broadens the definition of labor beyond carpentry and into a humanistic exploration. These paintings were hopeful assertions that are crucial to Lawrence’s humanistic underpinnings; they demonstrate communal work and effort to create change.[17]

Builders- Man on Scaffold exemplifies the formal elements demonstrated in The Builders Family and is visually similar to Schomburg Library; this implies they have more in common in content than at first glance (fig. 5). The two paintings share a simple palette of brown, grey, and primary colors that fill the vertical composition. The main figure of either image stands in the center apex of the composition with the tools of their labor in hand; the man on the scaffold holds a clamp while the figure in the library carries several books. Bookshelves serve as the platform to elevate the figure in Schomburg Library while the builder is lifted by the scaffolding. Other figures within the compositions recede into the background and populate each with a diverse selection of experiences. In an interesting parallel, the woman in Builders- Man on Scaffold cradles an object in a similar pose as a figure; this illuminates how closely related the images are in compositional arrangement. The woman cranes her neck to the side to look down gleefully at what she is holding, possibly books, and the construction of a building carries on next to her. Holding the same pose, the figure in Schomburg Library positions their left arm underneath the novel and bends at the neck to get a closer look as the active consumption and building of knowledge takes place next to them. The open windows in Builders- Man on Scaffold serve as a telescope into the lives of the community as they carry out everyday tasks indicative of a genre scene. This intimate sight into surrounding buildings is mimicked in the Schomburg Library by images that reference the content of the novel on its cover. Harriet Tubman’s silhouette is reflected on the dust cover of one of the novels to serve as the audience’s window into the contents.[18] These visual similarities highlight the treatment of both subjects as laborious; paralleling the physical labor of construction with the intellectual labor required by Lawrence to carry out the research to inform his art.

Diego Rivera, a Mexican muralist working throughout the early twentieth century, contributed public art that spoke to Harlem during the Depression, and Lawrence took notice of the socially-minded art being produced.[19] Rivera’s commissioned mural, titled Detroit Industry, for Henry Ford’s River Rouge factory is helpful for understanding Lawrence’s unconventional depictions of labor because it provides a point of comparison between his human-centered compositions and Rivera’s hybrid focus of the worker as a machine (fig. 6, fig. 7).[20] Made in 1932, Detroit Industry immortalizes Ford, a large production factory with a sizable workforce, while having a critical outlook on the intense capitalist property that perpetuates commodity fetishism.[21] In contrast to Lawrence’s Builders- Man on Scaffold, Detroit Industry is heavily focused on the machinery that comprises the factory. Meticulous attention is paid to the intricacies of the machinery required to build Ford’s automobiles, and Rivera relegates that product to a barely visible location in the background.[22] Detroit Industry, North Wall centralizes the apex of movement within the machine where technicians are dwarfed on

all sides by the towering equipment. Like Lawrence, Rivera believed the laboring process itself is important to depict, however, Detroit Industry portrays the human workers as an efficient workforce that becomes as rhythmic as the machinery itself. The individuality of labor and experience is stripped away.[23] The volume of bodies works as one entity that appears to have no other desires outside of labor.[24] The subjective human experience is centered in paintings such as Builders- Man on Scaffold; analog tools are the supporting element to the laborer themselves. To Lawrence, the human subject is essential to a painting to communicate with the viewer.[25] In comparison with Rivera’s mural, the focus on individuals and communities shine with optimism throughout Lawrence’s depictions of labor. This is exemplified by Lawrence when he says “…Man’s struggle is a very beautiful thing… The struggle that we go through as human beings enable us to develop, to take on further dimensions.”[26] The focus on struggle and development is seen in both the depictions of physical labor in scenes of builders as well as libraries; the material for this development is different, but the goal is the same.

The library represented a place for Lawrence to learn from his community in the present by attending the lectures and community meetings held there.[27] He listened to historians in his community, and eventually, he would follow in their footsteps to become a historian in his own right. Not only were his paintings documenting stories of black heroes and heroines told to him by his teachers and librarians, but he was actively recording events and people on the streets in the present to continue his own historical education.[28] Both the historical figures within the pages of novels and the actual people Lawrence observed in the library provided a variety of subjects of Lawrence’s paintings. Lawrence’s depictions of libraries demonstrate the vast evolution of style over decades while remaining consistent in composing reading figures as the focal point of the image. The Libraries are Appreciated silhouettes the patrons by the shelf teeming with books, their figures are contrasted in red and white draws the eye to their activity. The horizontal composition, simple color palette, and still figures create a calm environment; this convention is invigorated with movement and color in later depictions of the same location such as the Schomburg Library.

While the main figures in these compositions are typically construction workers, Lawrence’s observations about labor under the Builders theme expand beyond that definition.[29] The universality of labor transforms these images into near genre scenes.[30] Lawrence views labor in Builders- Man on Scaffold within the framework of human skill and production that happens within a small community; Schomburg Library demonstrates a similar production and cycle of knowledge that happens within a select group. In order to portray historical figures and events in an informed way, he had to accept the responsibility of developing a historical sense which, as Arthur A. Schomburg stated, was a slow and difficult process.[31] Learning about, researching, and creating the archive is in itself a form of labor, different from construction or building a family, but an immense responsibility. Visually paralleling Schomburg Library to Builders-Man on Scaffold broadened the perception of labor beyond physical work to include intellectual labor that is required to interpret historical documents.

- “Harlem Walking Tour: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,” One Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence's Migration Series (MoMA, 2015), https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2015/onewayticket/walking-tour/3a/. ↵

- Peter Nesbett and Patricia Hills, Jacob Lawrence: Thirty Years of Prints (1963-1993) (Bellevue, Wa: Bellevue Art Museum, 1994), 45. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence and Xavier Nicholas, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence,” Callaloo 36, no. 2 (2013): pp. 260-267, https://doi.org/24264907, 262. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence and Xavier Nicholas, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence,” 262. ↵

- Oral history interview with Jacob Lawrence, 1968 October 26. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence and Xavier Nicholas, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence,” 262. ↵

- Deborah Willis, “The Schomburg Collection: A Rich Resource for Jacob Lawrence,” in Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, 1st ed. (Washington, D.C.: Rappahannock Press, in association with the Phillips Collection , 1993): 34. ↵

- Willis, “The Schomburg Collection,” 35. ↵

- Lawrence, Nicholas, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence,” 262. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Clarence Major, and Jacob Lawrence. “Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, the Expressionist.” The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977): 22. ↵

- Clarence Major, and Jacob Lawrence, “Clarence Major Interviews," 18. ↵

- Patricia Hills, “Epilogue,” in Painting Harlem Modern, 266. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence and Xavier Nicholas, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence,” 264. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence (University of Washington, 1987): 176. ↵

- Ibid., 176-177 ↵

- Peter Nesbett, "Jacob Lawrence: The Builders Paintings," (1998), 14. ↵

- Nesbett and Hills, Jacob Lawrence: Thirty Years of Prints (1963-1993), 45. ↵

- Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” in Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Frobia W Simpson and Peter T Nesbett (Seattle, Wa: University of Washington Press, 2000), 102. ↵

- Anthony Lee, "Workers and painters: social realism and race in Diego Rivera's Detroit murals" in The social and the real: political art of the 1930s in the western hemisphere, 2006, 202. ↵

- Lee, "Workers and Painters," 202-206. ↵

- Ibid., 204. ↵

- Ibid., 208. ↵

- Ibid., 209. ↵

- Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, 4. ↵

- Hills, “Epilogue,” 270. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence and Henry Louis Gates, “An Interview with Jacob,” An Interview with Jacob Lawrence by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., no. No. 19 (1995): pp. 14-17, https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/4381286, 14-15. ↵

- Willis, “The Schomburg Collection,” 35; Lawrence, Nicholas, “Interview with Jacob Lawrence,” 261. ↵

- Lowery Stokes Sims, “The Structure of Narrative: Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence’s Builders Paintings, 1946-1998,” in Over the Line: The Art of Jacob Lawrence, 209. ↵

- Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, 157. ↵

- Arthur Schomburg, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” 1925: 670. ↵