13 Painting Human Suffering through a Universal Lens

Lawrence's Hiroshima

Ashley Tseng

Abstract

Jacob Lawrence was not one to overtly verbalize his political opinions, but how he dealt with themes of struggle, war, and protest give us a glimpse into how the artist’s ideologies and politics evolved throughout his career. In 1982, Lawrence was commissioned by the Limited Editions Club of New York to create a series of illustrations for a book of his choosing, and he chose John Hersey’s 1946 Hiroshima. Lawrence’s 1983 Hiroshima series consists of eight paintings that capture the suffering of Japanese civilians in scenes of everyday life at the moment of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima at the end of World War II.

This essay examines how Lawrence’s approach to representing war and political statements in his work shifted with his growing interest in creating universal statements about humanity and inhumanity. To understand the changes in how Lawrence expressed his politics as an artist, it is valuable to consider Lawrence’s experience in the United States Coast Guard during World War II. In the Hiroshima series, Lawrence depicted an event from American history that is connected to a larger universal history and the future of humanity. Lawrence’s strong values of community create an empathic narrative in the Hiroshima series that represents the horrific experience of the bombing victims through a universal and humanist lens.

The Challenge of Universal Struggle in Hiroshima

In 1982, Jacob Lawrence was asked by the Limited Editions Club of New York to create a series of illustrations for a book of his choosing.[1] The book he selected was John Hersey’s 1946 Hiroshima, which tells the story of six individuals who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan on August 6th, 1945 at the end of World War II. The paintings Lawrence made were translated into silkscreen prints that would be used as illustrations for a special edition release of Hersey’s book.[2] Lawrence’s Hiroshima series (1983) consists of eight tempera and gouache paintings that each show a different scene of daily life: a family inside their home, farmers in a field, people in a park, a man with birds, a street scene, children at a playground, a boy with a kite, and a marketplace. These paintings capture the horrific moment in which the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, interrupting and stealing away the lives of innocent Japanese civilians.

Throughout his career, Lawrence created many works portraying war and struggle, such as his Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954-56) and his War series (1946-47). Lawrence often drew upon his own experience as a black American in his work to represent universal struggle when creating scenes of American history. In the Hiroshima series, however, the artist took on a different challenge: painting an event that never experienced. The result was a vision of history as seen through the eyes of the victims of the United States’ actions in war.

Lawrence’s dedication to humanism and portraying universal struggle can be seen throughout his career, but this does not mean his approach to creating political statements in his work remained static throughout his entire life. As I will argue, the Hiroshima paintings focus on the suffering of individuals to portray war through a humanist and universal lens. By combining themes of war, struggle, and community, Lawrence created scenes of human suffering that evoke empathy and create an antiwar statement that speaks to all of humanity.

Humanism and Empathy in Hiroshima

In the Hiroshima series, Lawrence intentionally avoided representing the figures with Japanese features. As he told biographer and student Ellen Harkins Wheat, he did not think he could have properly depicted the physical features of the Japanese people and he “didn’t think it was important either.”[3] If Lawrence had chosen to paint Japanese features, he could have easily fallen into the dangerous territory of stereotyping and creating an “othering” of the Japanese civilians, especially since there is a long history of American media portraying the Japanese and Asians as a different and even “uncivilized” species in racist propaganda. For example, right after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there were many American editorial cartoons that showed caricatures of the bombing victims with stereotypical Japanese features being “blown to pieces” by the atomic bomb.[4] Lawrence’s decision to paint human figures without clear racial or ethnic indicators reflects his dedication to creating a universal statement in an event that he and his community did not personally experience .

The main color palette of the Hiroshima paintings consists of bright reds, yellows, blues, and pinks. Wheat describes this combination of colors as “oddly dissonant” but in a way that effectively reflects the horror of the bombing.[5] The forms in the Hiroshima series are fragmented and made up of jagged lines, in contrast to Lawrence’s typical use of strong linear planes and outlines in his previous works, such as his Migration series (1940-41) and Struggle series (1954-56). In Hiroshima, most of the figures have their heads tilted upwards and are staring at the sky, which clearly marks them amidst the tragic moment in which the atomic bomb has been dropped. Figures are stripped of the skin and features on their faces; only their skulls remain. We may feel disturbed by the skulls and bright red flesh of the figures, but Lawrence does not allow us to turn away in disgust. Instead, he works to evoke empathy by placing these figures in common scenes of daily life such as eating with family, sitting at a park, and going to the market, which are able to resonate with most people regardless of cultural background.

Although the Hiroshima bombing was not an event that Lawrence experienced, he drew upon his personal experiences to paint it. In the panel entitled Family, the blast strikes down upon a family of four sitting at a table during their mealtime (fig. 1). The scene echoes multiple other works by Lawrence that take on the theme of family, such as The Family (1964) and This is a Family Living in Harlem (1943), which often show family members gathered together at a table sharing a meal. Lawrence is using daily scenes of life that he has seen in his own community to create the Hiroshima series. For instance, the scene of children flying kites in Hiroshima: Boy with Kite (fig. 2) is one that he has painted before in 1962, with Street Scene (Boy with Kite). Lawrence’s chooses to paint activities that are seen in many different cultures and not just unique to Japan. Furthermore, his inclusion of children among the figures in the Hiroshima series further intensifies the emotional impact of the work. Lawrence’s depiction of child victims of the bombing emphasizes the innocence and loss that this atrocity caused. The scenes in the eight Hiroshima paintings together as a series gives us a look into a dimensional human community that has just been struck by the inhumanity of nuclear war.

While we can see the skulls of the figures peeking through their burning flesh, the settings surrounding them remain somewhat intact and recognizable. For instance, in Hiroshima: Family (fig. 1), the walls of the house are still standing and although the table and chairs look warped and are on the verge of breaking, they remain upright and able to support the sitting family members. Rather than focusing on the atomic bomb’s destruction of infrastructure, Lawrence emphasizes the suffering of the civilians, which reflects his identity as a humanist who is committed to focusing on human content in his work. In the year following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, U.S. military reports focused on the “strategic damage to the buildings, bridges, and other war-related infrastructure” rather than describing what had happened to the Japanese civilians who were victims of the atomic bomb.[6] By concentrating on human suffering rather than damage to infrastructure, Lawrence subverts the narrative that the U.S. military had tried to perpetuate and spread to the public.

Patriotism and Protest

When examining Lawrence’s images of war, we can see the artist’s inner conflict with patriotism and protest that arose from the tension between his past experience serving in the U.S. military during WWII and his desire as an artist to express human suffering that is inseparable from war. During his time in the military , Lawrence was a member of the Coast Guard and served on the U.S.S. Sea Cloud, which was the first naval boat with a racially integrated crew.[7] The integrated groups of servicemen working together in harmony were a major focus of the paintings he created while deployed. Art historian John Ott argues that Lawrence’s Coast Guard paintings and War series show the artist’s advocacy for racial integration within and beyond the military, an institution that Lawrence once called “the best democracy I’ve ever known.”[8] After Lawrence’s experience in the Coast Guard, we see him gain a stronger fascination with showing human struggle and experience within the larger theme of universalism. For instance, The War series (1946-47), painted by Lawrence not long after his military service came to a close, takes on a much darker and muted palette than his earlier paintings of community and shared labor amongst the boat’s integrated crew. The works from the War series portray integrated groups of black and white WWII soldiers, but rather than focusing on harmony and collaboration, Lawrence highlights their shared experience of struggle and trauma. War Series: Beachhead (fig. 3) is one such vision of psychological turmoil. In the intense scene of black and white American soldiers fighting together and supporting each other in battle, the struggle of war and its destructive nature are captured through the injured soldier being carried on a stretched amidst the battlefield. Decades later in the Hiroshima series, Lawrence would return to these themes, confronting the atrocities committed by the U.S. government and military on a global scale.

To understand Jacob Lawrence through the lens of patriotism and activism, it is important to consider the pressures he may have faced due to his connections to government-funded arts programs, his position as a black artist who was active during the McCarthy era, and his service in the U.S. military during WWII. All these aspects of his experience add to the challenges Lawrence faced in creating political statements, but they are also what make his art so politically and socially complex. During the 1940s and 1950s in the United States, The Red Scare and McCarthy era targeted communism and accused many artists of having leftist affiliations. Art historian Patricia Hills has suggested that Lawrence’s endorsement of progressive causes and organizations put him at risk of being targeted by anticommunist politicians in the United States, like many other artists at the time.[9] The Hiroshima series acts as a form of a protest and social commentary, as these paintings were made in the midst of the nuclear arms race during the cold war. However, the political message in Hiroshima feels more directed towards the entirety of humanity rather than the United States government or military. Lawrence also must have had to reconcile the fact that the United States’ supposed “fight for democracy” identified communism as its ideological enemy, and directly resulted in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the start of an era marked by the threat of nuclear warfare.

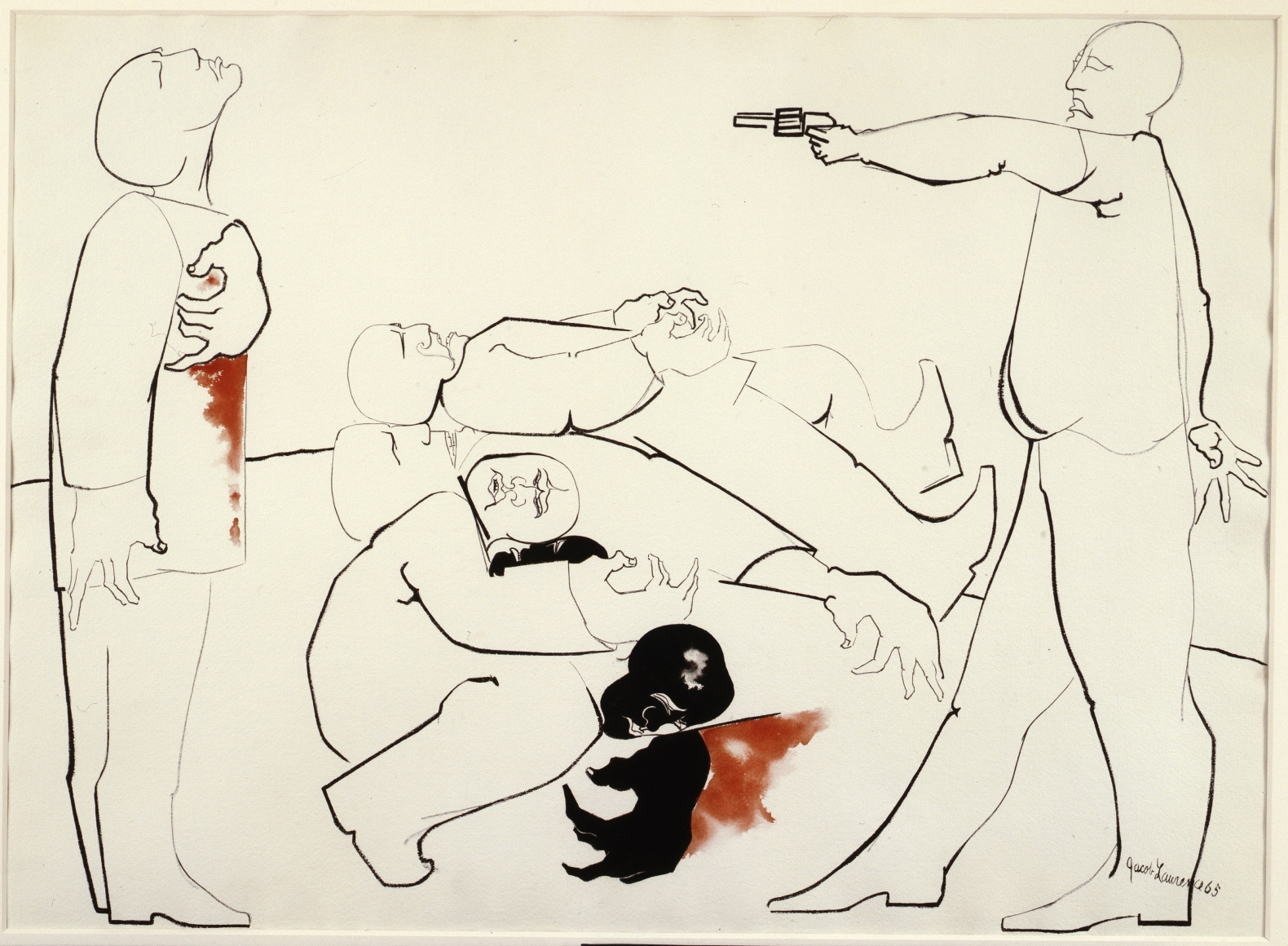

Similar to the scenes portrayed in the Hiroshima series, Lawrence’s protest works of the 1960s are designed to capture human struggle in a manner that evokes empathy and resonates universally. In 1965, Lawrence created Struggle III—Assassination (fig. 4) as part of a series of ink drawings that portray scenes of police brutality. In the black and white drawing of Struggle III—Assassination, the only pop of color comes from the two washes of bright red ink used for the blood of the injured civilians. In this piece, Lawrence uses flat washes of black ink to clearly depict two of the civilians as black, while the race of the other figures is left ambiguous. By focusing on human struggle rather than race, Lawrence is able to frame police brutality and the fight for civil rights as an issue that concerns humanity as a whole. 1965 was also a time in which the antiwar movement was gaining prominence in the United States.[10] Lawrence donated Struggle III—Assassination to be used for the Artists’ Call Poster in January 1984, for an organization that was protesting U.S. military policies in El Salvador.[11] This goes to show how even though Lawrence served in the military during WWII and admires the integration he had experienced in the Coast Guard, he still had a strong commitment to creating works that condemn oppressive acts perpetrated by American authorities. Patrick B. Sharp discusses how the “U.S. military seemed most concerned with suppressing or refuting stories that discussed human suffering in Hiroshima.”[12] Although the Hiroshima series was created almost forty years after the bombing, the act of choosing to create illustrations for Hersey’s Hiroshima, and painting the horror inflicted upon Japanese civilians by the United States’ decision to use the atomic bomb, is a significant act of protest.

Painting War and Struggle

Lawrence’s Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954-56) series and War series do not glorify war, but they also do not contain a powerful antiwar statement like the one that is overwhelmingly visible in the Hiroshima series. In his Struggle series, Lawrence highlights the contributions of marginalized peoples’ role in American history. In a 1968 interview with art historian Carroll Greene, Lawrence describes how black people have been excluded from American history and not acknowledged for their role in building the nation. European immigrants were “all mentioned as to their contributions,” but the contributions made by black Americans went unrecognized and unappreciated by historians.[13] Lawrence’s Struggle series and War series shows us a more integrated narrative of United States history and society that does not exclude people of color. And with the Coast Guard works, John Ott states that Lawrence “adopted a contributionist viewpoint, advocating a more egalitarian and far-reaching integration than that disseminated by military publicity agencies .”[14] Ott’s argument shows how Lawrence believed in a more integrated future that encompasses all aspects of American society. Lawrence’s contributionism focuses on emphasizing black peoples’ role in building the United States, and also their struggles and achievements. Although Lawrence’s contributionist approach in the Struggle series, War series and his Coast Guard paintings helps highlight and tell the stories of marginalized peoples who have been exploited and left out of American history, the celebratory nature of focusing on contributions can make it difficult to condemn the United States’ history of war. For instance, in the War series and Coast Guard paintings, we can see the patriotism, struggles, and valuable contributions by black Americans during WWII, but until the Hiroshima series, we do not see the other side of the war that suffered from U.S. military decisions.

Although Lawrence’s War series might not condemn the U.S. government or military, they do demonstrate the struggles and trauma experienced by the soldiers. In the 1947 painting War Series: Going Home (fig. 5), Lawrence depicts a racially integrated group of American WWII soldiers aboard a ship on their journey back home. The blue color palette of the panel creates a melancholy atmosphere that shows the harsh reality of war. However, even though the soldiers are injured and clearly suffering both physically and mentally, they still have a home to return to. In the Hiroshima series, Lawrence is depicting civilians entangled in the war rather than soldiers. War has infiltrated their home: they can neither leave nor return. The theme of home and community in Going Home and the Hiroshima series helps humanize the figures inside his art and emphasize their struggles. However, in Hiroshima, Lawrence is painting the story of the Japanese civilians who had their lives, homes, and communities taken away by the atomic bomb.

To represent the destruction of life and a tragedy he did not personally experience in the Hiroshima series, Lawrence said he used various symbols such as flowers and trees in the process of dying.[15] This use of nature as symbolism can also be seen in panel 26 of Lawrence’s Struggle series, titled Peace (fig. 6). In Peace, the landscape is dried and cracked, but there are still new flowers sprouting through the ground, symbolizing a new beginning and hope for the nation after the War of 1812. However, in the Hiroshima series, nature appears to have been devastated beyond repair. For instance, the trees in the People in the Park painting are fragmented and devoid of life (fig. 7). The charred and frail branches are on the verge of collapse and eerily frame the park goers who had been peacefully sitting on benches at the moment of the explosion. The absence of optimism in the Hiroshima series emphasizes the universal statement Lawrence creates to warn humanity about the irreparable damage of nuclear warfare and its degree of inhumanity.

Universalism, Community, and Lawrence’s Experience

With the Hiroshima series, Lawrence stated that he wanted to create a universal statement addressing “man’s inhumanity to man.”[16] And previously in 1961, when reflecting upon his Struggle series, Lawrence had called it a turning point and said that “years ago, I was just interested in expressing the Negro in American life, but a larger concern, an expression of humanity and of America, developed.”[17] The Hiroshima series can be considered a further evolution of Lawrence’s desire to express a larger vision of humanity that extended beyond his personal background. He conveyed a narrative of U.S. history in which Americans are not the main characters, and instead centered the story on the Japanese civilians and on their suffering.

Art historian Paul J. Karlstrom has argued that in Hiroshima, Lawrence “declares his independence from group — indeed from community — and his participation in the broader humanist discourse.”[18] I disagree with this assessment. Instead, I argue that community and a universalist approach are not mutually exclusive in Lawrence’s works. Lawrence’s development of embedding universal messages into his works does not sacrifice his dedication to community. In fact, we see how Lawrence takes his own experiences to create an empathetic portrayal of the Hiroshima bombing victims. W hen talking about his approach to the Hiroshima series, Lawrence said: “I used my own experience. How people live, people at the table, in the park, in the marketplace. I didn’t follow something out of the book.”[19] The activities and setting in the Hiroshima series are not distinctly Japanese, they are scenes that are familiar to not only Lawrence, but also people all over the world. The Hiroshima series can be seen as a culmination of Lawrence’s ability to represent war, struggle, and scenes of daily life drawn from his own personal experiences. And through this approach of using his own experiences to paint the human suffering of others, Lawrence creates a universal message that condemns the inhumanity of war.

- Peter T. Nesbett, Jacob Lawrence : The Complete Prints, 1963-2000 : A Catalogue Raisonné (Seattle: Francine Seders Gallery, in Association with University of Washington Press, 2001), 42. ↵

- Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, The Complete Jacob Lawrence (Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 190. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” PhD diss., (University of Washington, 1987), 194. ↵

- Patrick B. Sharp, "From Yellow Peril to Japanese Wasteland: John Hersey's “Hiroshima”," Twentieth Century Literature 46, no. 4 (2000): 438. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 194. ↵

- Sharp, "From Yellow Peril to Japanese Wasteland: John Hersey's “Hiroshima”," 440. ↵

- John Ott, "Battle Station MoMA: Jacob Lawrence and the Desegregation of the Armed Forces and the Art World," American Art 29, no. 3 (2015): 59. ↵

- Ibid, 74. ↵

- Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 207. ↵

- Patricia Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Paintings during the Protest Years of the 1960s,” In Over the Line: the Art of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, (Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 184-186. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 195. ↵

- Sharp, "From Yellow Peril to Japanese Wasteland: John Hersey's “Hiroshima”," 440. ↵

- Jacob Lawrence, “Oral history interview with Jacob Lawrence,” interview by Carroll Greene, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, October 26, 1968. ↵

- Ott, "Battle Station MoMA: Jacob Lawrence and the Desegregation of the Armed Forces and the Art World," 67. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 194. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “Reading History: Recovering Jacob Lawrence’s Lost American Narrative,” in Jacob Lawrence: the American Struggle, ed. Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Austen Barron Bailly, (Salem, Massachusetts: Peabody Essex, 2019), 30. ↵

- Paul J. Karlstrom, “Jacob Lawrence: Modernism, Race, and Community,” in Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, (Seattle: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 241. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 194. ↵