4 The Materials of Change

Jacob Lawrence on Migration

Alexander Betz

The Great Divide

Early in 1973, just two years after his move to Seattle, Washington, Jacob Lawrence painted The hardest part of the journey is yet to come – the Continental Divide, stunned by the magnitude of the roaring rivers (fig. 1), a scene from his series on Pacific Northwest pioneer George Washington Bush. The painting centers upon Bush who, rifle in hand, braves the Rocky Mountains at the helm of a covered wagon. Grasping tendrils of snow creep up to Bush’s mount, while the horse drawn carriage is engulfed in a flurry. The horse’s hooves still trod upon the green grass of the east, each step pulling the party deeper into the wild. Bush himself rides stalwart at the front in parallel with another man, each of them enduring the brunt of the high alpine exposure as they lead their diverse band of peoples over a mountain pass. Nature itself watches on, as elk high upon the mountain slopes bear witness to the courage of the settlers. In Lawrence’s work to migrate is to endure, and to learn from such endurance. One can only hope that the promises of the destination are worth the trials.

Jacob Lawrence was no stranger to migration, and his depiction of George Washington Bush in The Great Divide is one of many in a long lineage of his works capturing Americans in transition. Indeed, Lawrence’s own life was punctuated by moments of movement, from his birth in Atlantic City to parents who had traveled north as part of the Great Migration, to a journey south as an instructor at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina, to an eventual move westward to assume a professorship at the University of Washington in Seattle. Using this theme of migration as a foundation, this essay will explore the intersection of three main elements of Lawrence’s work: First, this essay will inspect the relationship of materiality within Lawrence’s work. Of interest will be physical attributes that link pieces together within a series, such as paint types and pigments. From here, this essay will seek to understand how Lawrence uses the serial format to develop a narrative. The serial format appears in Lawrence’s work as the cooperation of a multitude of individual panels all presented in unison to speak towards different aspects of an installation’s greater message. For example, The Great Divide comes as panel three in a series of five paintings chronicling the migration of George Washington Bush from east to west. This essay will then arrive upon a closing question: how does this development of migration in Lawrence’s work impact his view as an educator? In this essay, I intend to explore Jacob Lawrence’s construction of migration through materials and serial narrative as an expression of community development and education.

Jacob Lawrence’s construction of narrative in series and expression of materiality can be found in the pigmentation of the paints he selected. Opting to create paints without changing the mixture or intensity of pigmentation between panels, Jacob Lawrence would use such mediums “…so that the colors would not vary from one panel to the next” (Steele 2000, 250). Through allowing his paints to stay unmixed, and painting in a manner in which he worked on multiple pieces at the same time, a whole series of pieces became tightly knit together. For example, this commonality in hue can be seen in the comparison of panels within the George Washington Bush series.

The beginning of the series is introduced through the piece On a fair May morning in 1844, George Washington Bush left Clark County, Missouri, in six Conestoga wagons (fig. 2), depicting the beginning of the journey west for Bush and his fellow pioneers. As the sun shines resplendent through the clouds, rays of fire-gold thrust themselves through the picture plane. Evocative of a gold-lit roadway, these dazzling sunrays bring the ephemeral promise of westward hope. It is a hope not yet tested, and one still of unfettered promise. In contrast, bookending this series is the panel Thank God All Mighty, home at last – the settlers erect shelter at Bush Prairie near what is now Olympia, Washington, November 1845 (fig. 3).

Within this piece the same fluorescent yellow can be found, its pigmentation unbroken across the span of the series. However, now the sparkling motes of light take the shape of kicked-up saw dust as they obscure figures toiling to erect their new homestead. Where the sunrays of the first panel speak of a naïve promise west, the haze of debris in the closing piece speaks to a more realistic, tangible future in Bush’s new home. By using an unbroken linkage of color between these two panels Lawrence has produced a developing narrative of progress for his subject. What was once the airy desire for a better life has become a cloud of hard work and promise, where heavenly light at the outset of the journey has transformed into the debris of labor. Jacob Lawrence maintained a consistency in the pigmentation of this color between these two panels, and in doing so laid their connection. Indeed, the physical relationship of panels in a series through their pigmentation was something that Jacob Lawrence established throughout the development of the work. Art Historian Elizabeth Steele remarks that Jacob Lawrence, “with all of the prepared panels laid out, [would] systematically apply color to each one” (Steele 2000, 250). In this way, it is likely that the application of the yellow hue in the Bush Series was one that happened simultaneously between panels. This linkage between Lawrence’s paint pigmentation and content is present in more than the only his George Washington Bush series, where similar themes of American movement are also present in his The Migration Series.

The Migration Series

Painted between the years of 1940 and 1941, Lawrence’s Migration Series chronicled the passage of black Americans north from the bitter truths of a Jim Crow south. On display within Lawrence’s depiction of the Great Migration is what scholars Lonnie Bunch and Spencer Crew identify as a “…complex narrative [that did] not romanticize the massive transition from rural South to urban North” (Bunch and Crew 1993, 26). One of these complexities on display within The Migration Series is the transition from agrarian labor to one of a different kind: education.

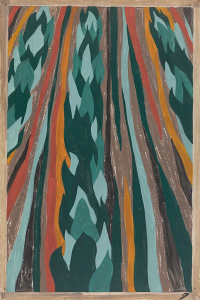

In panel 7 of Lawrence’s Migration Series, entitled The Migrant, whose life had been rural and nurtured by the earth, was now moving to urban life dependent on industrial machinery (fig. 4), rows of tilled farmland stretch across the canvas. In sweeping vertical strokes, the burnt hues of orange and red breath dimension into the fertile soil. One can picture running their fingers through this dirt, leaving crimson clay trapped under their nails. Lawrence seeds this ground with parallel rows of plant life, where sea-green leaves of teal and cyan rise and fall like the spines on a dragon’s crest. The viewer is given no sky, no background, only a solid singular picture plane bearing bands of unbroken color to illustrate the agrarian landscape of the south. Filled with verdant life, this panel implies hard labor. As scholars including Leah Dickerman have observed, all of these crops needed to be planted, and overwhelmingly the labor force of the southern economy relied upon black Americans (Dickerman 2015, 20). However, Lawrence captures the expanding scope of labor available to the migrants as these communities moved north in exodus. In panel 58 of The Migration Series, entitled In the North the African American had more educational opportunities (fig. 5), Jacob Lawrence constructs a classroom scene of three black female students.

Reaching up with chalk in hand, they create a line of ascending numbers on the blackboard. And yet, notice the colors of the three students’ dresses: one is a burnt red, another orange, and the last a sea-tinged cyan. These are the same pigments used for the southern farmland in panel X, unchanged and now intimately involved with an institution of education. Through the use of a fast-drying tempera paint, Lawrence was able to jump between panels quickly and with instant visual feedback to construct these threads of connection (Dickerman 2015, 20). More than a mere formal device, the shared color between the fields and crops of the south and the school dresses of the north established a conceptual narrative of development. Through migration, the individuals involved with this journey north had the promise of a future rich with academic potential. What were once the terracotta earth tones and resplendent greens of Carolina fields have become the very drapery of educational achievement. The materiality of Lawrence’s work allowed for him to make this visual connection, where the unbroken color between panels established a narrative from southern farming to northern education. The hues Jacob Lawrence has selected to depict these two images never change, instead they merely travel across the frame as they rearrange and take on their new scene – not unlike the migrants themselves.

On Education

Jacob Lawrence’s own life was influenced by migration, which helped to build his outlook on education. Remarking on his understanding of such travel, Lawrence stated: “To me, migration means movement…Uprooting yourself from one way of life to make your way in another involves conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle comes a kind of power, and even beauty” (Rodgers 1992, xxi). Throughout the scenes of the George Washington Bush series and The Migration Series, conflict and struggle play a key role. However, this kind of power and beauty Lawrence speaks to can be found in how migration causes a development of education. Lessons that Jacob Lawrence gathered from his role as an educator at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College in the summer of 1946 would come play a preeminent role in his pedagogy. After completing his move to the city of Seattle to teach at the University of Washington in 1971, Lawrence was asked to reflect upon his past experience as a teacher, to which he replied: “Teaching is a two-way thing. It has enabled me to learn and expand in ways I may not have, both in my work and in my thinking” (Lawrence 1975, 3). These words are emblematic of the academic environment found in North Carolina. Under the direction of Josef Albers, a notable artist of the abstract expressionist movement and educator at the Bauhaus school in Germany, educators and students alike came together without a clear hierarchical division between either group (Caro 2020, 133). However, this impactful experience in Lawrence’s life did not come without the struggle of movement across the United States. Jacob Lawrence described his experience returning back home to New York from North Carolina with his wife Gwendolyn Knight as “…something we’ll always remember. We were put into a Jim Crow car, Jim Crow section, the two of us” (Caro 1998, 135). This experience came just five years after Lawrence’s completion of the Migration Series, and the racism he experienced as a part of this journey northwards was similar to the very discrimination on display within that work. However, in response to this discrimination, Lawrence remembers that “…many of the students from Black Mountain came back to join us, which was some gesture…What they were saying of course was ‘We’re supporting you’” (Caro 2020, 135). If Lawrence’s teaching was characterized by his empathetic method of a “two-way street,” then it was moments like this that would have built the deep respect between teacher and student inherent within that method. The solidarity of the students while on this journey with Lawrence showed how communities can pull themselves through the trials of migration. George Washington Bush faced the biting winds of cold during his party’s crossing of the Rockies in The Great Divide, and in this moment on the train north it was the wickedness of the Racist policies of the Jim Crow south that plagued the Lawrence’s. However, just as George Washington Bush would go on to use the strength he found in his journey west to found a home for himself and his community, it was the solidarity shown to the Lawrence’s by the students that Jacob Lawrence would return to as an educator at the University of Washington twenty-five years later. The materiality of Jacob Lawrence is something that will not leave him as he undertakes movement across the United States as well. Migration in Lawrence’s work does not only capture a journey to that which is new, but also a strengthening of the core principles that have come along for the ride. This appears in Lawrence’s own relationship with the materiality of paint in his work. In an interview in 1977, Jacob Lawrence recalls that he “…started working in poster color because it was so inexpensive back then in the late thirties…it’s fast to work with, and really suited for [his] working in series form” (Lawrence 1977, 1). While his usage of water based paint began because it’s what was accessible for a young artist, this preference for the fast drying paint would remain throughout all of Jacob Lawrence’s career. As Barbara Earl Thomas would explain about Jacob Lawrence’s teaching style, “Jake was always looking at what his students were doing and trying to get them to do it better, as opposed to trying to get them to look like [his] work” (Caro 2016, 80). Sticking to what comes genuinely from one’s self was at the core of Lawrence’s pedagogy. This intersects with the materiality of Lawrence’s work, where his water-based mediums would be tested through his entire life’s migrations and yet continue to remain at the center of his process alongside the serial format.

…

Jacob Lawrence used migration as a recurring theme in his work just as it was a recurring experience in his own life. In his series on George Washington Bush, the movement of settlers to the southern shores of Washington State’s Puget Sound was imbued with a narrative progression of migration. Jacob Lawrence used unchanging colors of yellow-gold to characterize the transition of Bush’s party from one of untested hope to real and rewarding hard work found in the construction of a new community. The journey west was educational for the settlers, where nature itself was an obstacle that must be overcome to ensure that they will have the resolve required at their destination. Educational development is also on display in Jacob Lawrence’s series The Great Migration, where simultaneously applied hues are used between panels to construct a narrative of northward promise. As Jacob Lawrence’s colors shift in form from scenes of the agrarian south to a northern classroom, the unbroken pigment of his work sings the promise of migration. These developments of education through migration would come full-circle back into Lawrence’s own life, where his experience journeying south to teach at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina would remain pivotal to his role as an educator. While that journey was fraught with social challenge, Jacob Lawrence’s legacy as an empathetic educator who valued equality with his students was forever strengthened. Lawrence would continue to use the same paints and materials to paint in a serial format as he did as a young artist in New York City all the way through to the end of his career in Seattle. For, on Jacob Lawrence’s canvas, migration and education are one and the same. Education is a journey, and the goal of migration isn’t only to find something new. Instead, it is to find what is so powerful and true to one’s soul that it may endure the challenge of any change.

Bunch, Lonnie G., Elizabeth Hutton Turner, and Spencer R. Crew. “A Historian’s Eye: Jacob Lawrence, Historical Reality, and the Migration Series.” Essay. In Jacob Lawrence – the Migration Series, 23–31. Urbanna, Virginia: Rappahannock Press, 1993.

Caro, Julie Levin, and Jeff Arnal. Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence + Black Mountain College. Asheville (C.): Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, 2019.

Major, Clarence, and Jacob Lawrence. Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, the Expressionist. Other. The Black Scholar 9 3, 1977.

Miller, Barbara to Lawrence, Jacob, 1975, Box 5, Folder 14, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers, 1816, 1914-2008, bulk 1973-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Rodgers, Lawrence R., and Jacob Lawrence. Essay. In Canaan Bound: the African-American Great Migration Novel, xii. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Steele, Elizabeth. “The Materials and Techniques of Jacob Lawrence.” Essay. In Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, edited by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle W DuBois, 247–65. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation, 2001.

Turner, Elizabeth Hutton, and Leah Dickerman. “Fighting Blues.” Essay. In Jacob Lawrence – the Migration Series, 10–31. Urbanna, Virginia: Rappahannock Press, 1993.

Van Rensburg, Janse, Levin Julie Caro, and Carroll Greene. “Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, Summer 1946.” Essay. In Jacob Lawrence: Lines of Influence, 131–44. Zurich, Switzerland: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, 2020.